Elevator pitch

The escalation in chief executive officer (CEO) pay over recent decades, both in absolute terms and in relation to the earnings of production workers, has generated considerable attention. The pay of top executives has grown noticeably in relation to overall firm profitability. The pay gap between CEOs in the US and those in other developed countries narrowed substantially during the 2000s, making top executive pay an international concern. Researchers have taken positions on both sides of the debate over whether the level of CEO pay is economically justified or is the result of managerial power.

Key findings

Pros

CEO pay is market-determined and reflects the bidding by firms for scarce executive talent.

The increasing percentage of externally hired CEOs points to rising competition for top talent.

CEO pay is in accord with historical norms in relation to the size of the firm, and the growth in CEO pay corresponds to the growth in firm size.

When magnified by the scale of the firm, the value of small differences in top executive talent is large, justifying top achievers’ high pay.

The increase in CEO pay is due to the rise in incentive compensation that links pay to firm performance and aligns the incentives of managers with those of shareholders.

Cons

The pay-setting process is unduly influenced by the CEO.

CEO pay is excessive in firms with weaker boards of directors, no dominant outside shareholder, and a CEO who has a large ownership stake.

Incentive compensation is manipulated to benefit CEOs even when firm performance is poor.

High CEO compensation increases the odds of a firm being selected as a peer group comparator for pay-setting purposes at other firms.

The extent to which CEOs reduce the pay–firm performance sensitivity in their compensation through the use of managerial hedging instruments is unknown.

Author's main message

Both sides of the debate over CEO pay implicitly acknowledge that self-interest motivates CEOs. Critics believe that structures to protect shareholders from excessive CEO compensation are inadequate, while advocates view pay as competitively determined. While both sides make a compelling case in this evolving literature, managerial power has exerted an influence on CEO pay. Although empirical evidence of effectiveness is lacking, measures that enhance the transparency of compensation packages and strengthen the voice of shareholders on pay issues might help move CEO pay toward just levels. Lengthening the vesting periods for equity-based compensation and stock options, though not necessarily to the same extent for all firms, might help improve incentives.

Motivation

Uproar over high executive pay often accompanies macroeconomic or stock market downturns—when the disparity in pay between top executives and regular workers is most unsettling and poor stock returns call executive performance into question. CEO pay warrants this attention because it is both large and growing in relation to firm financials.

Understanding the arguments for the level of top executive pay is important, as calls for regulation to inhibit pay levels are often heard. Indeed, various countries, including the US, have enacted regulations to do just that.

Discussion of pros and cons

International comparisons

Concern over CEO pay is not limited to the US, although most research on executive compensation considers US firms. The US case is instructive because new research shows a convergence in the level and structure of CEO pay between the US and other developed countries. Conventional wisdom is that CEO pay in the US far outstrips CEO pay in other countries. CEO pay in the US is high relative to pay in other countries, but this gap mainly reflects the larger size of US corporations. New evidence suggests that, after accounting for firm size differences and other factors, CEO pay is converging internationally.

A comparison of 14 developed countries found that US CEOs earned about twice as much as their foreign counterparts without accounting for any differences between them [2]. After statistically controlling for factors including firm size, industry stock price volatility and performance, growth opportunities, and ownership and board structure, the US CEO premium fell to 26% in 2006 and to 14% in 2008.

The remaining pay premium may largely be the result of compensating US CEOs for the additional risk in receiving more of their pay in equity-based compensation. The convergence among countries in the level of pay and in the forms of compensation is the product of internationalization, including the competition in the international labor market for top executive talent and the demands of internationally diverse corporate boards and institutional shareholders for performance pay.

Trends in US CEO pay

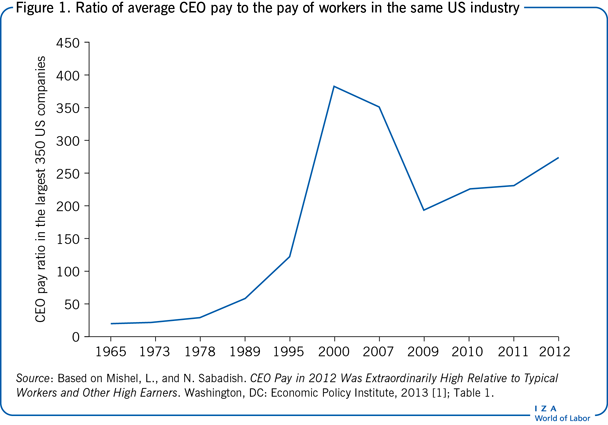

In 1970 the average Standard & Poor's 500 CEO earned about 30 times the pay of an average production worker. By 2002, this multiple had risen to almost 90 times in cash-only compensation, and more than 360 times in total compensation. The trend in the ratio of average US CEO pay to the pay of workers in the firm's industry for the largest 350 US firms shows a similar jump [1] (Figure 1).

But the average CEO compensation level is somewhat misleading as a summary statistic because of the influence on the mean of outliers. The distribution of US CEO compensation is quite skewed, causing the mean to be more than twice the median. CEO pay levels are also quite dispersed, differing substantially both within and across industries. The inflation-adjusted median pay of Standard & Poor's 500 CEOs increased at an annual average rate of 4.3% from 1983 to 1991, and 15.7% from 1991 to 2001, and the acceleration in the 1990s was due to a rise in stock option grants [3].

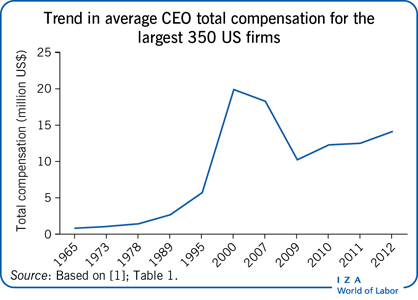

The Illustration depicting the trend in average CEO total compensation in the 350 largest US firms during the period from 1965 through 2012 appears to be almost the mirror image of the trend in the ratio of average CEO pay to typical worker pay over the same period in Figure 1. This is because the changes in the pay ratio in Figure 1 that take place over time are overwhelming due to the changes in the average level of CEO pay and not due to changes in typical worker pay. In this 47-year period, average CEO pay including the value of stock options exercised increased over 16-fold, while, in contrast, in the same time period typical worker pay increased by just 30%.

Disconcerting to those concerned about the plight of typical workers or about rising earnings inequality in general is the fact that most of the 30% pay growth for workers occurred in the years just following 1965. In fact, almost two-thirds of the 30% growth in typical worker pay came during the eight-year period from 1965 to 1973. The rate of pay growth for typical workers has slowed noticeably in recent decades.

In the years after World War II to 1970, CEO pay levels were low, concentrated, and moderately sensitive to firm performance. Before 1950, CEO compensation consisted primarily of a salary and annual bonus [4]. A change in the tax code in 1950 allowed stock option gains to be taxed at a lesser rate. Despite the tax code change, options were a minor influence on median CEO pay until the 1970s. All elements of compensation escalated from the mid-1970s through the 1990s.

At the same time, the dispersion in pay across firms and top executives grew. Stock options expanded rapidly in the 1980s to become the largest component of CEO compensation by the 1990s, and the link between pay and performance was strengthened. Stock options accounted for almost half of US CEO compensation in 2000. Much of the rise in overall CEO compensation was accounted for by the increasing importance of stock options, although other forms of compensation were increasing as well. With the growth in the dispersion of CEO pay, the distribution of pay became more skewed, and the average grew relative to the median. The growth in pay was more pronounced among larger firms, and CEOs benefited from the growth more than other high-ranking executives in the firm.

In the 2000s, average CEO pay fell, and restricted stock grants overtook stock options as the most common form of equity-based compensation [4]. Levels of executive compensation have fallen in other periods as well. So, it is not the case that CEO pay rises continuously. To some extent the academic debate over CEO pay has focused on its rapid growth following the mid-1970s, while the decline in CEO pay in the 2000s and the shift from stock options to restricted stock have not yet been the focus of a large body of research.

Executive pay is already heavily regulated in the US. However, the measures regulating pay have largely been ineffective, or even counterproductive, in restraining CEO pay [5]. That cautions against the call for more regulation, as does the fact that such regulations have unintended consequences, such as the rise in perquisites in the 1970s, “golden parachutes” (e.g. benefits such as severance pay, bonuses, and stock options provided when an executive's employment is terminated) in the 1980s, stock options in the 1990s, and restricted stock in the 2000s. The US adopted legal measures during the 1990s and 2000s to increase board independence, and board independence has increased since the mid-1980s. But these regulatory measures did not reduce CEO pay [3].

Executive labor markets and efficient contracts

A primary argument for high CEO pay is that the market for executive talent is competitive, and the pay results from the bidding of firms for scarce talent. Furthermore, it is argued that pay is efficiently structured to address incentive problems within the firm and that the increase in CEO pay reflects the growing importance of general skills in running the modern corporation and the trend toward more externally hired CEOs, up from 15% in the 1970s to more than 26% in the 1990s [3].

The sharp gain in CEO pay has been attributed by some to the adoption of high-powered incentives in compensation packages due largely to increased CEO holdings of firm stock and stock options. The increase in CEO compensation is viewed in this light as compensation for the additional risk in pay from the rising sensitivity of compensation to changes in the firm's stock price.

In fact, the public focus on the level of CEO pay might be misplaced, because it shifts the focus from the more important issue of how CEOs are paid, and the link between CEO pay and firm performance.

The strength of the relationship between CEO pay and firm performance is thought to be important because the separation between ownership and management in corporations gives rise to an agency problem in which managers pursue their self-interest over the interests of shareholders. The increase in the components of pay linked to firm performance—stock option schemes, for example—is viewed as aligning the incentives of managers with the incentives of shareholders to combat the agency problem.

There is a well-documented relationship between firm size and executive pay whereby the CEOs of larger firms are more highly paid. For those believing that CEO pay is competitively determined, the higher pay of the CEOs in large firms is viewed as necessary to direct the most talented executives to the larger firms where the value of their talent is magnified by the larger scale of the enterprise. The value of CEO talent might depend not only on the size of the CEO's firm but also on the size of outside firms competing for CEO talent.

Research suggests that the growth in CEO pay is commensurate with the growth in the size of firms. The six-fold increase in CEO pay at large US companies from 1980 to 2003 matches the six-fold increase in the market capitalization of the companies during the period [6]. Subsequently, average total firm values fell by 17% during the crisis of 2007–2008 and rebounded by 19% in 2009–2011, while CEO compensation fell by 28% and then rebounded by 22% [7]. These coordinated movements between firm values and pay help to substantiate the notion that CEO pay is competitively determined and that pay levels reflect the value of talent magnified through the scale of the firm. From this perspective, the often-noted ratio of CEO pay to the pay of the average or median worker is not the appropriate metric upon which to compare the pay levels of CEOs. The average pay levels in the firm have little, if any, bearing on the monetary value of the CEO's impact on the firm. Instead, the CEO's effort and talent and the size of the firm would have a bearing on the CEO's impact. Accordingly, the ratio of CEO pay to a measure of firm size, such as the market value of the firm, may have been a better choice for mandated disclosure by the US Securities and Exchange Commission in 2013 than the ratio of CEO pay to median employee pay [8].

Advocates of efficient and competitively determined CEO pay may find it difficult to explain some elements in compensation trends and administration [3]. There was no reduction in other forms of compensation during the run-up in stock option grants during the 1990s. The value of the options awarded should have substituted to some extent for other forms of compensation. Accordingly, the number of at-the-money options granted by firms should have declined with increases in the stock price because the value of such options increases in proportion to the price. Instead, the number of options increased during the 1990s. Nor is there an explanation for why stock options were granted to the lower-ranking workers in the firm when their individual actions have negligible consequences for the firm. Perhaps corporate boards simply do not fully understand how much stock option grants cost the firm [3].

Irrespective of the argument that CEO pay levels serve as market prices to efficiently allocate talent across firms in the economy, the argument that high CEO pay levels serve as an incentive device for retaining lower-ranking executives within the firm also exists. According to advocates of tournament theory, executives in the firm are competing with each other for promotions to higher-level positions. In this framework, high levels of CEO pay create incentives for executives in the ranks below the CEO to compete for promotion to the top spot. For these promotion incentives to be beneficial to the firm, the competition that takes place must not manifest itself in destructive ways or diminish teamwork. Getting ahead by hindering one's competitors in the firm might be just as effective in winning the promotion competition as exerting a high level of productive effort.

Managerial power

The pay-setting process could be unduly influenced by the CEO, who may have substantial influence over the composition of the board of directors, the compensation committee determining CEO pay, and the selection of the compensation consultant advising the compensation committee. While people can be upset by the contracts given to professional athletes, an athlete's pay is the result of an arm’s-length negotiation between a team owner and the athlete's agent. It is argued that CEO pay is not the product of arm’s-length negotiation between two parties with opposing interests in the matter because the CEO does not bargain against the owner of the firm. Since the ownership of a corporation is dispersed, the corporate board sets CEO compensation and has little desire to oppose the CEO in doing so. Furthermore, comparisons with the pay at other firms through salary survey data are pervasive in setting pay levels. Since most firms elect to be at or above pay levels in the comparison firms, an annual escalation in pay results.

To a large extent the rise in US CEO pay since the early 1990s resulted from CEO pay-setting practices that have prevailed since the 1970s [9]. Pay levels in a peer group of comparator firms are a benchmark in setting the pay of the given CEO. Each year a small share of CEOs jumps to the right tail of the CEO pay distribution. These CEOs, through serving as a benchmark for other CEOs, produce a rise in overall CEO compensation. This phenomenon potentially explains a significant portion of the increase in CEO compensation in the 15 years after 1993.

Irrespective of the influence exerted by outliers in the CEO pay distribution on overall compensation levels, the practice of setting pay itself provides ample degrees of freedom for manipulating the outcome. The selection of the members of the peer group for benchmarking pay is to some extent subjective and can be manipulated to produce a more highly compensated peer group. Indeed, a high level of CEO compensation increases the likelihood of a firm being selected as a peer group comparator. Given the peer group, the firm's targeted position within it may also produce an escalation in pay as most firms aim to be at or above the median or mean of the peer group in pay. While the use of peer groups to benchmark CEO pay can exert a substantial influence, it also provides a mechanism to retain the CEO by considering the incumbent's market wage.

Supporting the managerial power hypothesis is evidence that CEO pay is higher in firms with a weak board of directors, no dominant outside shareholder, and a manager possessing a larger ownership stake. Higher CEO pay has also been associated with firms that have more outside board members appointed by the CEO, more board members serving on three or more boards, board members with a smaller ownership stake in the firm, and CEOs who also serve as chairman of the board. Further evidence suggests that powerful CEOs are able to increase not only their own pay but also the pay of their subordinates. On the other hand, the managerial power hypothesis struggles to explain the rise in CEO pay in recent decades, because corporate governance appears to have been strengthening as corporate boards contain more external directors, proxy fights and takeovers have grown more prevalent, and shareholder activism has increased [6].

Six features of CEO compensation practices might be argued to support the influence of managerial power on pay [9]:

First is rewarding executives for their firm's stock price movements without removing the component due to the movement of the overall market.

Second is the general failure of firms to award stock options to CEOs with a strike price above the market price (out-of-the-money options).

Third is resetting option exercise prices when the firm's stock price falls below the exercise price.

Fourth is the lack of a prohibition against executives hedging against the risk in their equity-based compensation, since this risk is meant to improve CEO incentives.

Fifth is granting stock options just before the announcement of good news.

And sixth is backdating options to past low points in the firm's stock price.

CEO pay is not ideally structured to provide for the most direct link between pay and performance. It is possible for elements of CEO equity-based pay to be contingent on the firm's stock performance relative to general stock market performance or industry performance. Instead, the CEO's return on stock and stock options holdings includes the price movements in the overall market, making the link between the CEO's performance and pay less direct.

Compensating executives for the movement in the overall stock market or in the firm's overall industry is akin to compensating them for luck. Indeed, CEOs are compensated just as much for identifiable luck in firm performance as for firm performance generally [10]. However, in better-governed firms, such as those with a major shareholder on the board of directors, the strength of payment for luck is reduced. This argues in favor of the CEO having an influence over the pay-setting process. In addition, there is a lack of symmetry in the payment for good versus bad luck. The penalty for bad luck has a weaker effect on CEO compensation than the reward for good luck. The average US CEO loses about 25% less from bad luck than they gain from good luck.

Recent research has a bearing on the issue of rewarding executives for their firm's stock price movements without removing the component due to the movement of the overall market in two respects. First, the notion that compensating executives for the movement in the overall stock market or industry, rather than for the isolated movement in the firm's value after adjusting for these broader movements, is necessarily inefficient is disputed. Recent economic theory does not conclude that CEO equity-based pay must be contingent on the firm's relative stock performance in order for pay to be structured efficiently [8]. Second, recent evidence for the US and UK defies the prevailing sentiment that relative firm performance is absent from the determination of CEO pay [8].

While the agency framework has provided a justification for stronger pay for performance and higher contingent compensation, executives have to some extent responded by seeking to avoid the risk created through managerial hedging instruments. Due to lax disclosure rules and little interest of market participants in voluntary disclosure, it is unknown to what extent executives use managerial hedging instruments to reduce the presumed sensitivity in pay for firm performance. An article in the business press states that in 2000 at least 31 US company executives reported engaging in hedging [11]. The problem is that hedging removes the basis for awarding stock-based compensation in the first place, because it negates the link between pay for performance and the incentives that were supposed to be created. For those engaged in hedging, the rise in total compensation attributable to an increase in performance pay is unjustified.

While a great deal of attention has been paid to the link between pay and performance in the literature, there are some potential drawbacks to awarding performance-based compensation. In regard to awarding stock options these include incentives for excessive risk-taking, a focus on short-term performance, and the incentive to manipulate or misstate the firm's financial performance.

In regard to a focus on the short term, CEOs awarded restricted stock and stock options tend to sell when the vesting period is complete. This results in an increased sensitivity to the stock price in this time window. Research shows that the behavior of CEOs is altered in years in which they have consequential amounts of equity vesting [12]. These periods are associated with reductions in investment in research and development, advertising and capital expenditure, and an increased likelihood of meeting or exceeding earnings forecasts. This finding implies that CEOs manipulate the company's investment path for personal gain by meeting short-term earnings forecasts to the benefit of stock prices.

In the same vein, it has been shown that CEOs release more discretionary company news in months in which they have equity vesting. This positively affects the stock price and market liquidity in the short term, allowing the vested equity to sell at boosted prices [13].

Limitations and gaps

The large literature on executive compensation cannot be neatly categorized into arguments that either justify pay levels as the result of well-functioning labor markets and efficiently structured contracts or deem them the result of excessive managerial power. Some facts may be claimed in support of either category, and some may support neither. Exclusive consideration of these two opposing views overlooks other potentially significant factors influencing pay levels, such as the influence of government and the role of regulation [3].

Other areas of CEO compensation have not yet received much attention in the literature. Before changes in US disclosure rules in 2006, broad data on perquisites, pensions, and severance pay were not available [4]. Perquisites include such benefits as: the personal use of company aircraft; personal and home security services; tax and financial planning services; insurance premiums; company cars; personal drivers; tax reimbursements; and club memberships.

Based on the limited available empirical research, perquisite consumption could represent managerial excess. Pensions constitute a substantial fraction of the total amount earned over an executive's term as the CEO. Failure to consider pensions has implications both for the level of CEO pay and for the sensitivity of pay for performance. Severance payments, awarded upon retirement or termination, have also received limited attention in the research on CEO compensation.

Summary and policy advice

A balanced view of the debate over CEO pay would suggest that managerial power has exerted an influence on CEO compensation, explaining some features of compensation and bearing some responsibility for the escalation in CEO pay. Pay has also been influenced by labor market conditions and the desire to strengthen executive incentives. The uproar over pay levels, the recent disclosure laws, and the greater scrutiny of corporate governance may also have had an effect on the structure and level of pay.

Four measures would, on basic principles, find favor among economists:

First, firms should disclose the expected value of all CEO compensation on the grant date, even though disclosure has not been shown to reduce pay levels. This would reveal the cost of retirement benefits, severance packages, and so forth.

Second, the voice of shareholders should be strengthened in matters of executive compensation and board member selection. Again, empirical evidence that this would reduce CEO pay is lacking.

Third, limiting the CEO's freedom to sell stock and exercise options by lengthening the vesting horizon would help to avoid a short-term focus in decision-making, reduce the CEO's incentive to manipulate the firm's stock price, and keep the firm from needing to issue new equity-based compensation to restore the incentives lost after the exercise of existing stock options or the sale of existing stock.

Fourth, when equity-based compensation is awarded to link CEO pay to firm performance, the executive should be prohibited from engaging in hedging to reduce the risk in compensation, since that would defeat the purpose of the compensation.

These measures are speculative and not based on conclusive empirical evidence, and the history of regulation dictates that any new regulation under consideration be carefully evaluated.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates research conclusions on executive compensation and stock market movement, explores CEO behavior during equity vesting periods, and adds new “Key references” [8], [12], [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Michael L. Bognanno