Elevator pitch

Reducing youth unemployment and generating more and better youth employment opportunities are key policy challenges worldwide. Active labor market programs for disadvantaged youth may be an effective tool in such cases, but the results have often been disappointing in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. The key to a successful youth intervention program is comprehensiveness, comprising multiple targeted components, including job-search assistance, counseling, training, and placement services. Such programs can be expensive, however, which underscores the need to focus on education policy and earlier interventions in the education system.

Key findings

Pros

Unemployed youth are a population at risk in many countries.

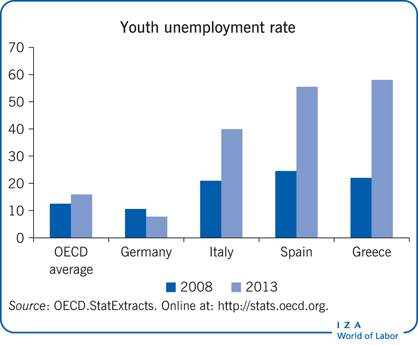

The average youth unemployment rate is twice the overall unemployment rate in most OECD countries.

Labor market programs that enhance human capital, such as training programs, can be an effective tool for increasing employment opportunities for disadvantaged youth, particularly in the long term.

Comprehensive labor market programs combining several components—job-search assistance, counseling, training, and placement services—can be effective.

Cons

Training and other active labor market programs for youth are frequently not effective in bringing them into employment in the short term.

Restrictive labor market institutions such as employment protection legislation and a minimum wage impede the effectiveness of active labor market programs.

Effective youth labor market programs are expensive.

The low success rate of youth active labor market programs underlines the importance of earlier interventions through the education system to improve school-to-work transitions.

Author's main message

Unemployed youth are a population at risk in many countries. In most OECD countries, the average youth unemployment rate is double the overall unemployment rate. This gap can be attributed to the lack of work experience and the weaker job search skills of young people and to structural problems, including inadequate education and training and overly restrictive regulation of labor markets. Active labor market programs can help, if they are comprehensive—including job-search assistance, counseling, training, and placement services—but they are expensive. Even more important may be earlier education system interventions to improve the school-to-work transition.

Motivation

Young people (generally those aged 15–24) who are out of work are a population at risk in many countries and need particular attention from policymakers. There are several reasons for the existence of these large groups of unemployed youth. First, in a persistent pattern in virtually all OECD countries over the last decades, the average youth unemployment rate has been about twice as high as the overall adult unemployment rate. Second, youth unemployment shows excess cyclical volatility, with young people’s unemployment probability during recessions exceeding that of adult workers [1]. Third, the youth unemployment problem is exacerbated by “scarring effects”: prolonged unemployment spells leave scars in the form of long-term negative impacts on earnings, employment, and other labor market outcomes. These scarring effects hurt young workers disproportionately because they occur early in the lifecycle and their negative impacts multiply over time [2].

Part of the unemployment gap between young people and adults can be explained by the relative lack of work experience and the weaker job search skills of young workers. However, research in recent decades suggests that structural problems also affect the labor market performance of youth. In principle, such problems can be tackled using several levers. One policy lever is education policies that improve the skills match between young workers and employers and help young people achieve a better school-to-work transition. Ultimately, achieving these goals requires policies covering the full education cycle, starting with early childhood interventions and lasting through the entire period of compulsory schooling and continuing into the system of vocational education and training. A second policy lever is the removal of barriers to youth employment. Two-tier labor markets that result from overly restrictive regulation of permanent employment contracts (such as employment protection legislation, restrictions on temporary contracts, and minimum wage regulation) likely create disincentives to hiring young workers or result in short-term entry-level jobs that become dead ends rather than stepping stones to more stable jobs.

Finally, another policy lever for reaching unemployed young workers is youth training and other types of active labor market programs, such as wage subsidies, public employment, and job-search assistance. These policies have been implemented to remedy structural and cyclical unemployment and have been used in OECD countries for several decades. This paper summarizes knowledge on the effectiveness of such training and other active labor market programs for youth in OECD countries.

Discussion of pros and cons

Youth labor market interventions target disadvantaged and vulnerable youth. In OECD countries, these categories tend to include all youth who are out of work. Typically, these unemployed young people are receiving some kind of welfare benefits.

More generally, low-skilled youth and school dropouts are also considered vulnerable. Active labor market programs may target the inactive group of youth—meaning those who are not in employment, education, or training. Most of the young people in this group are from low-income households. They have had difficult social backgrounds and limited education options. Finally, unemployed university graduates also constitute a target group for labor market interventions [3].

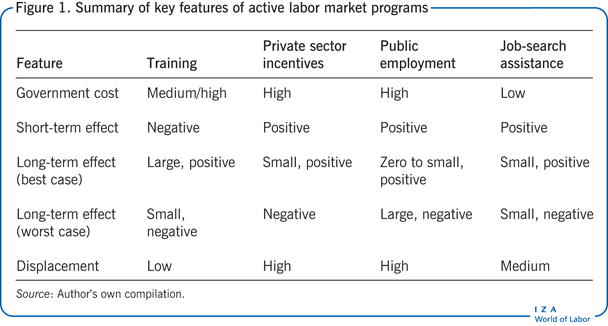

Active labor market programs are typically classified into four groups [4]: training programs, private-sector employment incentive programs, public employment, and job-search assistance. The following section defines these four types of active labor market programs and presents a basic framework explaining how the programs are intended to work. The key features of this framework are summarized in Figure 1. Later sections consider the evidence on the effectiveness of these youth employment programs.

A basic framework for active labor market policies

Training programs

Training programs—the classic active labor market policy—are the most frequently implemented labor market programs worldwide [5]. Training programs comprise all programs aimed at increasing human capital. The goals of boosting human capital and attenuating skills mismatch are attained through a set of training components: classroom vocational and technical training, work practice (on-the-job training), basic skills training (math, language), life skills training (socio-affective, noncognitive skills), and job insertion.

Because training programs increase human capital, the long-term effects are positive—and may be quite substantial. But because training takes time, negative effects on participants’ employment probability in the short-term are to be expected due to lock-in effects (during training, job finding rates are lower for training participants than for nonparticipants). The displacement effects of training programs (the extent to which subsidizing training might adversely affect other labor market participants or outcomes) are another possible negative outcome. These are likely to be small, however, for several reasons. Training participants might have been employed even in the absence of the program. And firms that employ participants in internships through subsidized training programs improve their position in the market relative to other firms that do not employ such subsidized workers. Of course, the effects will be negative if the training confers obsolete or useless skills. Government costs for sponsoring training programs are medium to high (see Figure 1).

Private sector incentive programs

Some labor market interventions create incentives that aim to alter employer or worker behavior. The most common of these programs is wage subsidies. Self-employment assistance is another type of subsidized private-sector employment program. Unemployed individuals who start their own business can receive grants or loans and sometimes advisory support for a fixed period of time. The main purpose of these programs is to improve the job-matching process and increase labor demand. There is also typically some limited human capital accumulation through work practice, and a culturization effect as participants get accustomed or re-accustomed to having a job.

These programs will have a positive effect only in the short term unless the subsidized work changes preferences for work or future employability (the “job ladder effect”). The risk of displacement effects is particularly high for these programs. Also, government costs are typically high.

Direct employment programs in the public sector

Some active labor market programs focus on public works or other activities that produce public goods or services. These measures are typically targeted to the most disadvantaged people, with the aim of keeping them engaged in the labor market and avoiding a loss of human capital during a period of unemployment. To some extent, these programs may also increase labor demand. Also, they can serve as a safety net (programs of last resort). Government costs are typically high.

Direct employment programs will have only a short-term effect on employment unless the work leads to a change in preferences or future employability. There is also a high risk of displacement effects. Finally, the jobs are often artificially created and are not integrated into the labor market.

Job-search assistance

Some labor market programs are designed to improve job-seeking skills and the efficiency of the search process and resulting job matches. Components typically include job search training, counseling, monitoring, and sanctions for failure to comply with job search requirements.

Job-search assistance will have only a short-term effect unless participants get a job that leads to changes in preferences or future employability. There is some risk of displacement effects, especially in a low-demand market. Government costs, though, are typically low for these programs.

Evidence on the effectiveness of active labor market programs

The evidence on active labor market programs in OECD countries shows that youth are a particularly difficult group to assist effectively [4], [5]. Relative to adult labor market programs, youth programs are significantly less likely to have positive impacts. In fact, only 20% of the youth programs reviewed in a meta-analysis found positive impacts [5]. This persistent finding is notably different from the evidence for other regions, most prominently Latin America and the Caribbean, where youth programs are typically more successful than in OECD countries.

Reasons for the dismal performance of youth programs in OECD countries can only be conjectured. Formal schooling systems in these countries are well-developed. The pool of young adults who are (long-term) unemployed consists of individuals with low qualifications and low skills, many of them school dropouts without a secondary school degree. Within a labor force that is, on average, fairly well-skilled and that has a large share of workers with a college degree, the youth targeted by active labor market programs are therefore a very disadvantaged group and may thus be difficult to assist. Across regions, the developed countries have among the strongest linear negative correlation between education level and probability of being unemployed.

Examples of successful programs

The few youth programs that do seem to work are comprehensive in design, with multiple components, and intensive in implementation. The two most important examples of successful youth programs in OECD countries are Job Corps in the US [6] and the New Deal for Young People in the UK [7], [8]. While the two programs differ in many details, they share the core features of comprehensiveness and high intensity. The program components comprise job-search assistance, counseling, training, and placement services. Similar positive results for comprehensive labor market programs have been found outside the OECD, in particular the Jóvenes programs in several countries of Latin America. These programs follow a multicomponent approach that integrates classroom training and work experience, life skills, job-search assistance, counseling, and information, and often include financial incentives for both employers and participants.

Because Job Corps and New Deal for Young People are rare examples of successful active labor market policies for youth, it is worth examining them in some detail here. Job Corps stands out as the largest and most comprehensive US education and training program for disadvantaged youth, serving more than 60,000 new participants a year at a cost of about $1.5 billion. A national program administered by the US Department of Labor, it began in 1964 with the objective of teaching eligible young adults the necessary skills to improve their employability and independence and place them in meaningful jobs or further education. Applicants must be 16- to 24-years-old, a legal US resident, and economically disadvantaged, and they must need additional education, training, or job skills. The program is committed to offering a safe, drug-free, education environment. Participants enroll in a 30-week course to learn a trade, earn a high school diploma or general educational development (GED) certificate, and receive assistance in finding employment. The program has four stages: outreach and admissions, career preparation, career development, and career transition. Career preparation is the profiling stage, career development is the core training stage, and career transition is the placement stage. Participants receive a monthly allowance during their training in addition to career counseling and transitional support for up to 12 months after graduation.

The US Department of Labor sponsored the National Job Corps Study—conducted from 1993 to 2004—to examine the effectiveness of the program. Results have been published in a series of reports and summarized in an article [6]. The impact evaluation is based on a large-scale randomized controlled trial with some 9,400 participants in the program group and almost 6,000 youth in the control group. The evaluation concluded that the program increases the education and training services received by participants by about 1,000 hours, the equivalent of a regular 10-month school year. At the same time, Job Corps measurably improves literacy skills. Statistically significant earnings gains were found for participants compared with youth in the control group in the first two years after program exit. These earnings differences between program and control group do not persist in subsequent years, however, except for participants who are in the 20- to 24-year-old group. Youth in this group, which constitutes about a quarter of Job Corps participants, typically remain in the program longer than in other programs and are more motivated and disciplined. Job Corps also significantly reduces involvement with crime for all subgroups.

However, while the benefits exceed costs from the perspective of individual participants, the benefits to society from Job Corps are smaller than the substantial program costs because overall earnings gains do not persist [6]. The benefits to society include increased lifetime earnings ($1,119 per participant), reduced use of other programs and services ($2,186), and reduced crime ($1,240). But the costs exceed the benefits by about $10,300 per participant. However, the program does appear to be cost-effective for the subgroup of 20- to 24-year-old youth, whose earnings gains persist even three to eight years after exiting the program.

The New Deal for Young People is a more recent labor market program. Launched in 1998 by the British government, it targets youth under the age of 25. The program is a key element of the government’s welfare-to-work strategy. The objective is to help unemployed youth increase their employability and transition into work. Participation is mandatory for all 18- to 24-year-olds who have been receiving unemployment benefits (Jobseeker’s Allowance) for six months or more.

Participants in the program first go through a period of job-search assistance before being offered training or alternative programs. In this initial “gateway” stage, individuals are assigned a personal adviser who gives them extensive assistance with job searching. If the participant is still unemployed and receiving a Jobseeker’s Allowance at the end of the gateway period (a maximum of four months), one of four New Deal options is available: full-time education and training, job subsidy (employers’ option), public employment (environmental taskforce), or voluntary work. All options last up to six months, with the exception of the full-time education and training option, which can last up to 12 months. With the other three options, employers are obliged to offer education and training at least one day a week, which is intended to lead to the attainment of formal qualifications. The third and final stage is a follow-through period with continuing advice and assistance to those remaining on assistance after completing their option.

Evaluation results suggest that the New Deal has led to a significant increase in outflows from welfare to employment and that the social benefits outweigh the costs. Unemployed young men are about 20% more likely to get a job as a result of the program. Much of this effect is likely due to the take up of the employer wage subsidy, but at least one-fifth of the effect is due to enhanced job search. Since the job-search assistance element of the New Deal program is more cost-effective than the other active labor market program options, the New Deal stands as the least costly comprehensive intervention for youth in OECD countries.

Factors influencing success or failure

For the majority of active youth labor market programs that show no positive effects other factors likely play a role. One factor is two-tier labor markets, in which insiders are well-protected, making it difficult for outsiders, in particular the young and low-skilled, to enter. France and Spain are typically cited as examples. There is evidence, for instance, that active labor market programs tend to be less effective in labor markets with stricter employment protection legislation: restrictive labor market institutions set up barriers to entry that young people are unable to surmount, even with the assistance of government programs. Such structural impediments may also play a role during the recovery from economic crises. In many countries, the large pool of unemployed youth in need of help then includes not only low-skilled youth and those not in employment, education, or training, but also many high-skilled and more highly motivated individuals.

Among different types of active labor market programs, public employment programs seem to be not only ineffective but often to result in negative treatment effects. The negative effects presumably occur because of the stigmatization of participants and because the type of public works programs that are commonly featured are unable even to maintain participants’ already deficient pre-program human capital.

Job-search assistance programs are often effective. Since these are typically fairly low-cost interventions, they also have a higher likelihood of being cost-effective. The evidence shows pronounced positive short-term impacts, that may, however, not always be sustained in the longer-term—as predicted by theory. Also, displacement effects may occur and reduce overall gains [3].

Wage subsidy programs also seem to be very effective, though once again there are questions about whether there are any positive employment effects in the long term and whether distortionary displacement effects can be ruled out. To date, these issues have not been convincingly addressed in program evaluation research. Another issue with wage subsidies is that distortions in the labor market become more likely the larger the scale of the intervention. That is, wage subsidies may be appropriate for specific target groups in well-defined contexts (sectors, regions) but may not be good candidates for large-scale public policy.

Labor market training programs are modestly effective, according to the average evaluation results for all programs to date. Since skills training is the most popular program and theoretically the most promising—due to its human capital formation component—it is worth looking at two further patterns found (for both youth and adults) in studies on training programs.

First, training impacts may be realized in the long term, sometimes the very long term [9]. Program evaluations looking at longer time horizons show that negative or zero effects over the short term often become positive over the medium and long term, but effects never go from positive in the short term to negative in the long term [5]. Moreover, there is increasing evidence that the most effective program sequence for unemployed individuals in OECD countries is to start with intensive job-search assistance, with counseling and monitoring, to achieve positive short-term effects, and then to move on to training, which yields positive effects in the medium to long term due to the accumulation of human capital [10].

Second, there is research indicating that training programs that do not lead to vocational degrees seem to reach their maximum effectiveness at about five to six months and that longer training does not noticeably improve participants’ post-treatment employment performance [11]. Training programs that do lead to vocational degrees are typically much longer (up to two years of training) and also show positive treatment effects [9].

Many OECD countries have tried to involve the private sector in some way in the provision of labor market programs, such as job placement services, but the evidence on whether this improves performance is inconclusive. However, a general case can be made for designing demand-driven, multicomponent (training) programs that incorporate private-sector enterprises through work practice and on-the-job training. As the evidence from Latin America and elsewhere shows, training can be effective if providers are selected through an open bidding process and required to collaborate with firms in the provision of their services. Also, an evaluation of active labor market programs in Turkey shows that contracting training to private providers can substantially improve results [12].

Another valuable conclusion from active labor market program research is that intervening early is better than intervening later. One reason is that early skills formation results in a longer payoff period. Yet another finding relates to the importance of capacity building, including social skills, before adulthood [13].

The effectiveness of comprehensive labor market programs (such as Job Corps, New Deal for the Young People, and Jóvenes programs) also points to the need to build integrated structures of skill formation. Important in this regard is the institutional relationship between vocational training programs and the formal education system—whether vocational training is integrated into education channels (like the dual system in Germany), which leads to greater success, or whether it is provided in a largely disconnected fashion, which does not.

Limitations and gaps

While research has identified several systematic patterns in active labor market programs, as discussed above, the literature on active labor market programs for youth shows that further evaluation efforts are necessary. The evidence to date has contributed greatly to the understanding of which type of youth active labor market programs seem to work. At the same time, many questions remain unanswered. For instance, most evaluations estimate short- and medium-term impacts, but few have examined the long-term effects of active labor market programs. Moreover, further investigation of the exact composition of multicomponent programs would be useful along with more evidence on the interplay between treatment length and program effectiveness. Cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses are rarely done, leaving a substantial knowledge gap.

New evidence on the displacement effects of active labor market programs is now being collected [3], but such studies require elaborate research designs, and more work is needed.

These examples of open questions point to the importance of continuing impact evaluation research to learn more about active labor market programs for youth. Program evaluation is important to appropriately inform policymakers and those who are responsible for implementing the active labor market programs.

Summary and policy advice

Youth labor market programs in OECD countries are significantly less likely than adult programs to be effective. The main reasons appear to be that the target group is composed predominantly of very low-skilled and disadvantaged young people and that many countries have two-tier labor markets with entry barriers (employment protection legislation, fixed-term contracts, minimum wages) that impede more effective operation of active labor market programs for youth.

At the same time, the empirical evidence shows a strong systematic pattern by program type, pointing to the long-term benefits of job training programs in terms of human capital formation. That suggests that training programs should receive particular attention by policymakers in youth active labor market programs. Even more important, successful youth programs need to be comprehensive, combining multiple treatment components, as experience with the New Deal for Young People program in the UK and Job Corps in the US has shown. Such multicomponent programs are expensive, but they can be effective.

Finally, the difficulty assisting long-term unemployed youth to enter the labor market points to the importance of education policies—to early interventions that can help steer young people into better education opportunities, thus smoothing the school-to-work transition and leading to more successful labor market outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Jochen Kluve