Elevator pitch

Denmark is often highlighted as a “flexicurity” country with lax employment protection legislation, generous unemployment insurance, and active labor market policies. This model has coped with the Great Recession and the Covid-19 pandemic, avoiding large increases in long-term and structural unemployment. The recovery from Covid-19 alongside re-openings has been swift, so labor market effects were temporary. A string of recent reforms has boosted labor supply and employment; although fiscal sustainability is ensured, demographic changes challenge the labor market. Real wage growth has been positive and responded—with some lag—to unemployment.

Key findings

Pros

Employment rates are high, increasing in recent years due to cyclical factors and structural reforms.

High job turnover rates ensure most unemployment spells are short, preventing increases in unemployment raising structural unemployment.

Resilience to the Great Recession and the Covid-19 pandemic has avoided sharp increases in long-term and youth unemployment.

Wage adjustment has been flexible, preserving wage competitiveness.

There are few working poor.

Cons

A large share of youth enters the labor market with a low qualification level; this is especially challenging because there are few low-skilled jobs.

Average working hours are low.

Job turnover may be detrimental to human capital accumulation.

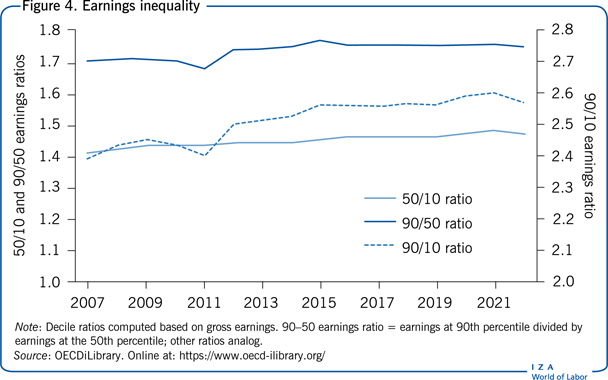

Wage inequality is widening moderately.

Demographic changes challenge the labor market.

Author's main message

Employment has trended upward in recent years and reached record high levels. Several reforms contributed to this development. The flexicurity model has been tested both by the Great Recession and the Covid-19 pandemic. It should be evaluated against its ability to prevent temporary falls in employment from becoming persistent and it has passed this test for the Great Recession—despite one of the largest GDP decreases—and the Covid-19 crisis. Job turnover rates are high in Denmark, implying that many are affected by unemployment, but unemployment spells are generally short. This prevents increases in long-term unemployment and eases labor market entry for youth. Wage inequality is rising, but less than elsewhere, and wage dispersion remains relatively low. Although reforms—in particular increases in the retirement age—ensure that public finances are sustainable despite an aging population, the workforce is shrinking as a share of the total population.

Motivation

The flexicurity model has been heralded for its ability to reconcile flexibility with social protection. The key ingredients are lax employment protection legislation, a relatively generous social safety net, and active labor market policies. It combines employers’ demand for flexibility with workers’ demand for income security and maintains work incentives via active labor market policies [1]. However, the flexicurity model is no guarantee against a recession, and the critical test is whether the model can cope with large negative shocks, support reallocation of labor, and avoid persistent unemployment. The Danish experience shows that the answer is affirmative. A crucial aspect is the high job-turnover rate, which has prevented long-term unemployment from increasing significantly in the wake of the Great Recession and the Covid-19 crisis. Global trends also affect the Danish labor market, and wage inequality has been rising though it remains low. The financial viability of the flexicurity model—and the welfare state more generally—depends critically on maintaining a high employment rate. The social safety net has recently been overhauled to strengthen labor supply and employment, including reforms targeted at the elderly, the young, the old, and immigrants. The main challenges calling for policy action are coping with demographic changes and the relatively large share of youth not obtaining education relevant to the labor market.

Discussion of pros and cons

The flexicurity model

Macroeconomic development has generally been favorable in recent years, and based on standard macroeconomic indicators, the economy has consistently performed well. Employment is high, and public finances and the current account display surpluses. The period prior to the Great Recession had high growth, and unemployment fell below the structural level. There were clear signs of overheating, with a booming housing market and accelerating wage increases. This was an unsustainable situation. Economic growth was already fading when the Great Recession set in, thus bringing the economy into a deep recession. The recovery was therefore relatively slow, although steep increases in long-term unemployment were avoided. The Covid-19 crisis differs from the Great Recession not only in the nature of the shock but also in relation to the pre-existing economic situation [2]. The lockdowns had both a supply and demand component; suppliers (firms) were constrained in their possibilities to sell, and demanders in their possibilities to buy. The emergency packages allowed most firms to retain valuable job-matches and production capacity (avoiding bankruptcy), but they also protected the income of workers and hence consumers, supporting consumer confidence and avoiding steep increases in precautionary savings. Hence, two classical persistence mechanisms, namely job-matching and decreases in aggregate demand, were muted by the policy initiatives. As noted, this should be seen in the perspective that Denmark entered the Covid-19 crisis with a well-performing economy, including low unemployment and sound public finances due to previous consolidation and reforms. Public debt is about 33% of GDP, which is among the lowest within the EU and well under the 60% baseline target. Consequently, there was fiscal space to pursue rather aggressive policies in terms of emergency packages, but also more traditional fiscal policy measures.

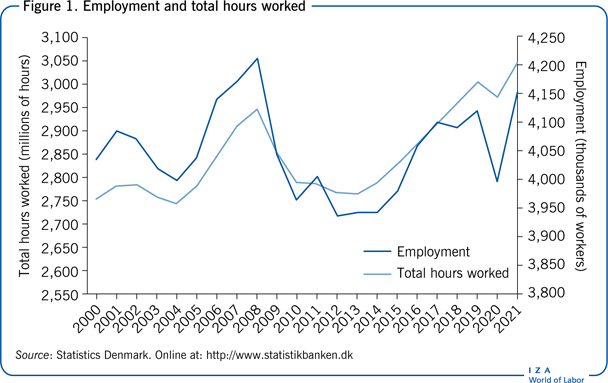

These phenomena are seen clearly in Figure 1, displaying developments in both employment and total working hours. Employment and working hours peaked prior to the Great Recession, and subsequently plummeted to recover only more gradually. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, employment reached a higher level, but importantly without the same signs of overheating as before the Great Recession. The employment decrease due to the Covid-19 crisis was muted by the wage compensation scheme introduced, and therefore the drop in working hours is a more accurate indicator of the effect of the crisis on economic activity [2]. The recovery has been swifter than in most other countries, and employment is now at a higher level than before the Covid-19 crisis.

The Danish flexicurity labor market has received considerable attention in recent years, especially for its ability to make a relatively generous social safety net compatible with a high employment rate [1]. It should be noted that employment rates—for both men and women—are among the highest within the OECD. This is in itself an interesting observation given the extended welfare state associated with the Nordic welfare model.

While the flexicurity model is no guarantee against business cycle fluctuations, the interesting question is how the model performs in a severe recession. Lax firing rules make it likely that employment will fall drastically when aggregate demand drops, and although the social safety net provides a cushion against large income losses among the unemployed, the financial viability of the model is at risk if structural employment decreases. A prolonged decline in employment reduces tax revenues and increases social expenditures, thus putting public finances under strain.

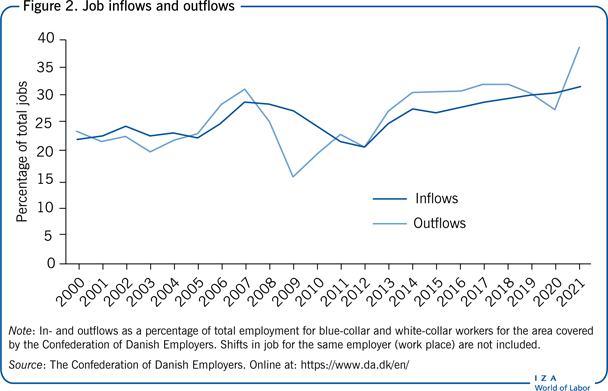

A key property of the flexicurity model is a high level of job turnover, implying that the unemployed (including youths entering the labor market) can find jobs fairly easily, and that most unemployment spells are short. Indeed, the data bear this out, as the general level of job inflows and outflows is high. Although job inflows plummeted as a consequence of the Great Recession crisis, they soon recovered, and the gross in- and outflow rates quickly returned to pre-crisis levels or even higher (Figure 2). The Covid-19 crisis did not change this. Outflows were high, but so were inflows, and unemployment in 2021 was at a lower level than beforehand.

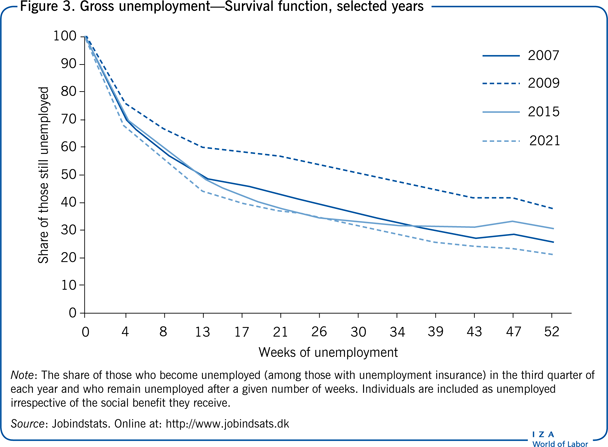

The resilience of the labor market can be illustrated by considering the duration of unemployment spells (Figure 3). In a normal year, 30% of unemployment spells are shorter than four weeks, and about 50% are less than three months. During crisis periods with increasing unemployment, exit from unemployment is lower, as illustrated by the 2009 numbers in the figure. But still, most durations are rather short. For 2021 the outflow from unemployment was close to (even better for long unemployment spells) what it was in 2015, which is often considered a normal business cycle year.

This high level of turnover in the labor market is also the driving force behind Denmark's comparably low levels of youth and long-term unemployment. Both are about half the EU average, during the crisis years and at other times too. High turnover rates thus effectively work as an implicit work-sharing mechanism. Equal burden sharing is important from a distributional perspective, but it is also of structural importance. The alternative would be longer unemployment spells concentrated among a smaller group of individuals, more long-term unemployed and a corresponding depreciation of human and social capital. In short, the high turnover rates reduce the negative structural potential of high unemployment.

A possible downside of the high job turnover is that it may be detrimental to firm-specific training. It is difficult for firms to protect investments in its workers’ human capital if the training is of relevance in other firms too. This may lead to a suboptimal level of investment in human capital with negative effects on productivity growth.

Flexible wages facilitate labor market adjustments

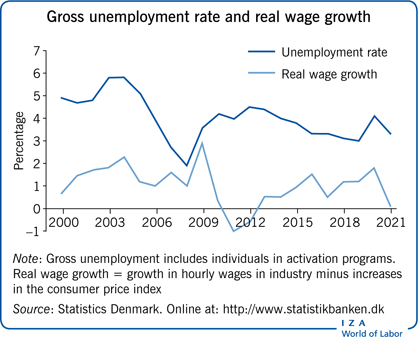

Real wage growth has been rather steady over the years, but with variations reflecting the business cycle. Most clear is the spike in wage increases, and the associated deterioration in wage competitiveness caused by the overheating prior to the Great Recession. Subsequently, wage developments have been more moderate, and real wage growth has gradually increased in response to the declining unemployment rate. The recent increase in employment has increased real wages, but only moderately. Wage flexibility—both upward and downward—has thus been relatively high by international comparison, and sluggish wage adjustment is not a key issue. This differs from labor market responses in the 1980s and 1990s, and can partly be attributed to a move from a highly centralized wage-setting system toward a model of so-called “centralized decentralization.” Collective arrangements retain their role as regulators of labor market conditions, while wage determination has become more decentralized [3]. The bargaining process follows a so-called pattern-bargaining sequence where sectors most exposed to foreign competition—industry—settle collective agreements before other sectors. For the public sector (which accounts for about one-third of total employment), wage bargaining takes place under a norm that overall public sector wage increases cannot exceed average wage increases in the private sector. The unanticipated surge in inflation with consumer prices increasing 9% in 2022 creates a new situation, and it is yet unclear whether a wage-price spiral will be triggered.

As in most OECD countries, wage inequality has followed an upward trend (Figure 4), though wage dispersion remains low by international comparisons. There are few working poor, and the number did not increase much during the crisis.

High employment rates and high share of population receiving transfers

The labor market situation can be assessed from two angles: one is the share of the working-age population in employment (as in Figure 1), and the other is the share receiving some form of public income support. The employment rate in Denmark is high by international standards, but so is the share of the working-age population receiving public transfers. The latter reflects more extended welfare arrangements, implying that most who are unable to support themselves are entitled to some form of public support. It is an immediate corollary that public finances are very sensitive to the employment rate; higher employment increases tax revenues and reduces social expenditures. Reform efforts have focused on reducing the share of the working-age population receiving social transfers. All types of social transfers have been overhauled with the aim of increasing labor supply and employment. These changes comprise both eligibility criteria and benefit levels. Several aspects of these changes are of particular interest, most notably when it comes to the youth, elderly, and immigrants.

Youth

The share of youth neither in employment, education, nor training (NEET) in Denmark is below the OECD average, but it has been on an upward trend. While much has been said about the Danish flexicurity model's ability to attain a low unemployment rate, the issue of youth entering the labor market with weak qualifications is a challenge [4].

The share of cohorts without education relevant for the labor market is a particular challenge. A key welfare state objective is to reconcile high employment with decent wages (i.e. no working poor). The wage structure is compressed, and minimum wages are high by international comparison, thus creating a situation in which the qualification requirements to find jobs are also high. This is important for maintaining a relatively equal distribution of income, but it is also a precondition for the financial viability of the welfare model.

The social safety net has recently been reformed to strengthen the incentive for all youth to acquire relevant qualifications. For individuals below the age of 30 (previously the critical age was 25) not having an education yielding labor market qualifications, the social assistance benefit level has been reduced such that it does not provide better compensation than study grants. Eligibility for support requires commencing education, or, alternatively, participating in an activation program.

These changes are aimed at reducing the number of NEETs. The experience so far is mixed. On the one hand, some evidence points to positive effects on employment and, in particular, on enrolment in education among the targeted groups. On the other hand, there have been only small declines in the share of youth depending on social benefits.

One criticism of this reform is that educational deficiencies should be targeted much earlier than when people are above the age of 20. Most people in the target groups have been enrolled in education before—without completing it—which points to the importance of early intervention (primary school or earlier) as a more effective tool in overcoming educational barriers.

The unemployment insurance scheme has also been reformed, affecting everyone in the labor market. Most important is a reduction in the maximum benefit duration from four to two years. The system has also been reformed to strengthen incentives to accept short-term jobs.

Elderly

The employment rate among age groups over 60 has increased steadily over the last ten to 15 years from a rather low level. Important for this development are reforms increasing the eligibility age for early retirement, shortening the period from five to three years, increasing the statutory retirement age in steps, and now indexing it to longevity. The eligibility age for early retirement is 64 years (from July 2023), and the statutory retirement age 67 years (in 2035 69 years). These changes have been motivated by increasing longevity and healthy aging as well as the need to ensure fiscal sustainability by increasing the relative share of a lifetime that people are working and thus contributing to the welfare state. One of the arguments against these changes has been that the job possibilities for the elderly are few. In a business cycle perspective, elderly workers are not more exposed to unemployment risks than young cohorts, but they may have a hard time returning to jobs. However, that does not preclude a high structural employment rate for the elderly, which was true in Denmark even during the crisis years. The employment rate for the age group 60–64 has increased significantly, from 54.5% for men and 36.1% for women in 2008, to 71.9% and 62.6%, respectively, in 2021. A more challenging aspect alongside increasing statutory retirement ages is the possibilities for individuals with reduced working capability (high morbidity and mortality) leaving work.

Migrant workers and immigration

Employment rates among immigrants vary considerably depending on the individual's reason for immigrating (study, work, refugee, family unification) and country of origin [5]. An inflow of migrant workers from EU (and associated) countries has been important for recent developments in the labor force. Thus, over recent years about one-third of the increase in employment can be attributed to an inflow of migrant workers.

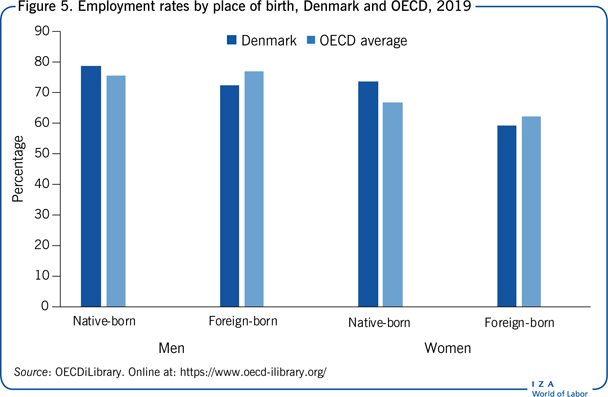

However, employment rates for immigrants from low-income countries (mostly refugees and family unifications) have been low and have attracted much attention. The issue can be viewed in two ways—by comparing either levels or gaps relative to other OECD countries, as in Figure 5. The level of employment rates for immigrants is not much different from what it is on average in OECD countries. The gap—that is, the difference in the employment rate relative to the native born—however, is large, especially for women. This reflects, of course, that employment rates are high in Denmark, so that it is more difficult for immigrant employment to reach this level.

The differences in employment rates between natives and immigrants may have numerous explanations. An important question is whether the design of the welfare model is an impediment to labor market entry for some immigrants. As noted, the Danish labor market is characterized by relatively high minimum wages and a compressed wage structure, which essentially eliminate being working and poor as an option. As a consequence, the qualifications required to find a job are relatively high, and low-skilled jobs are in short supply. Different cultures and norms for some immigrants with respect to gender roles may also play a role, especially for female employment rates. These effects may be compounded by language barriers, problems related to recognizing foreign educational qualifications, and possibly discrimination in the labor market.

The policy debate on immigration has been intense in Denmark, and various policy initiatives have been undertaken, including the tightening of immigration rules. Moreover, some changes in the social safety net have been prompted by immigration issues. The ultimate floor in the social safety net is the so-called social assistance, which provides economic support to those unable to support themselves and their family. A residence principle for eligibility was introduced in 2002, with eligibility for social assistance currently requiring residence in Denmark for nine out of the last ten years. In addition, there is an employment criterion requiring ordinary employment for an accumulated period of at least two and a half years within the last ten years (a further employment criterion has been added to target couples). Individuals not fulfilling these requirements are entitled to a different transfer (start aid/introduction benefit), equivalent to roughly half the value of social assistance. While these conditions did affect some Danes returning home after extended periods abroad, they had the largest effect on groups of immigrants with low employment rates, and who had been very likely to receive social assistance. These rules have been debated heatedly. They were abolished in 2012, reintroduced in 2015, and strengthened in 2019. The frequent policy changes reflect the sensitivity of the issue and the divided political views. However, the trend in recent years has been toward a tightening of the rules on both immigration and access to the social safety net.

Limitations and gaps

The labor market is affected by various structural changes, including automation and an aging population. This requires adjustment, and a particularly worrisome aspect is the large share of young cohorts not possessing labor market relevant qualifications. Since most youth do enroll in upper-secondary, post-secondary non-tertiary, or tertiary education, the main challenge is to increase completion rates, and earlier intervention may be called for to ensure that educational objectives can be reached. Ensuring high employment rates for immigrants also remains an important challenge.

Although employment rates are high, average working hours are low due to the prevalence of part-time work, especially in the public sector. It is easier to regulate labor market participation (the extensive margin) via entitlement conditions than it is to regulate working hours (the intensive margin). However, restrictions on working hours have been included in the entitlement conditions for social benefits, and tax reforms have been implemented to target working hours.

Reforms ensure that the criteria for fiscal sustainability are satisfied despite an aging population [6]. A key factor is the longevity indexation of statutory retirement ages. However, this indexation has a “speed limit” to avoid too steep increases in statutory retirement ages (a maximum increase of one year every fifth year). This is one reason why the public balance will have a profile with deficits followed by surpluses as statutory retirement ages catch up with longevity. The present value of the first sequence of deficits is covered by the present value of the later surpluses, and hence the fiscal sustainability criterion is met. Underlying this is an upward expenditure drift to cope with an increasing number of old residents. The labor market challenge is that the labor force is declining relative to the number of children and elderly, pointing to a tighter labor market. Issues of availability of labor and recruitment problems have been at the forefront of recent labor market discussions.

Summary and policy advice

The Danish experience shows that the flexicurity model has been able to cope with deep crises. Despite recent economic crises, the balance between flexibility and security has been retained. The model ultimately rests on its financial viability. Thus, even during the crisis, Denmark succeeded in launching forward-looking reforms to support high labor supply and employment. However, challenges remain. Ensuring that a high employment rate coexists with relatively low wage dispersion is difficult, particularly considering the problems arising from youths and immigrants entering the labor market with weak qualifications. Policymakers are working to address these issues via changes in the social safety net and education programs, but more action may be needed to reach the set objectives.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author (Andersen, T. M. “A flexicurity labor market during recession.” IZA World of Labor (2015): 173 and [1]) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article. Version 4 of the article updates the content and figures to 2022.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Torben M. Andersen