Elevator pitch

France has the second largest population of countries in the EU. Since 2000, the French labor market has undergone substantial changes resulting from striking trends, some of which were catalyzed by the Great Recession and the Covid-19 crisis. The most interesting of these changes have been the massive improvement in the education of the labor force (especially of women), the resilience of employment during recessions, and the dramatic emergence of very-short-term employment contracts (less than a week) and low-income independent contractors, which together have fueled earnings inequality.

Key findings

Pros

Massive furlough schemes have avoided employment ravages among permanent workers during the lockdowns and sanitary restrictions in 2020–2021.

The proportion of tertiary-educated workers is continuously increasing, while their employment rate remains high and acyclic.

The Great Recession did not stop the rise of the employment rate for women; it is now stabilized at its highest level since World War II.

The labor force participation of workers aged 50–64 has risen significantly.

Real earnings of the average and median full-time worker have risen until 2019.

Cons

Long-term unemployment and older workers’ unemployment never fully recovered from the Great Recession.

Spatial heterogeneity in unemployment is still large.

The use of very-short-term labor contracts (less than a week) has increased dramatically.

Annual earnings inequality has increased, driven by a decline in real terms at the bottom of the distribution.

New independent contractors replacing traditional artisans or involved in gig activities have low incomes and poor social protection.

Author's main message

According to unemployment (up to 2021) and inequality measures (up to 2019), the French labor market seems to have returned to the state it was in at the turn of the century. However, this simplistic view belies massive change. The educational attainment of the workforce has dramatically improved, pension reforms have stimulated the participation of older workers, and the employment rate has increased despite the 2009 and 2020 recessions. Women have also closed the gender gap in terms of unemployment, though men still enjoy higher wages. Looking ahead, policymakers must decide how to tackle persistent inequality, long-term unemployment, structural changes in low-income work, and the risk of a less employable generation in the wake of the education failures during the Covid-19 crisis.

Motivation

France is continental Europe's second largest economy, but suffers from an 8–9% unemployment rate, as just before the Covid-19 crisis. The country's inability to escape the unemployment trap it has been caught in for decades is still perceived as a major concern for the stability of the EU. The former OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurria described himself as having “enormous hope” for the reforms President Emmanuel Macron started in 2017. However, rather than focusing on “structural reforms” (that Covid-19 partially delayed), this article discusses important developments in the French labor market during the period from 2000 to 2021, which highlight some key current strengths and challenges for France in a post-Covid-19 era.

Discussion of pros and cons

Unemployment

Aggregate issues

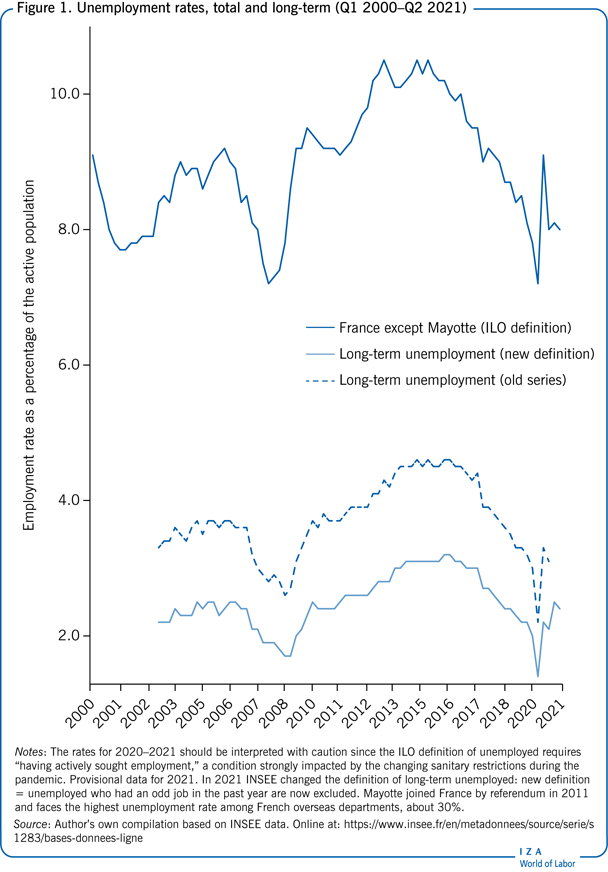

At the beginning of the millennium, French unemployment was still above 9%, according to the ILO definition. Even so, this was lower than Germany's rate, and down from its peak in 1997 (10.7%). France had benefited from a remarkable trend in 1998, 1999, and 2000, three of the four best years for job creation in the 20th century. In 2000, the Council of Economic Analysis (a non-partisan body attached to the prime minister) published a report entitled Plein Emploi, “full employment,” that expressed the economists’ optimism: according to this report, by 2005, France would have enjoyed an unemployment rate of around 5% thanks to steady growth, shortening working time, and the retirement of the massive cohorts of baby boomers. Unemployment in France did actually continue to decline, but slowly: by early 2008 it had reached its trough at 7.2%, far from the full employment objective (Figure 1).

The initial scenario was altered by disappointing GDP growth (less than a 2% yearly average) in the wake of the short recession in 2001, by the end of the policy supporting shortened work hours, and by the pension reforms that slowed retirement flows.

Some months before the Great Recession, there was again widespread optimism. The risk of labor shortages was even an argument for policies conducted by Nicolas Sarkozy (elected in 2007) to boost labor supply at the extensive and intensive margins, that is, via participation and hours (by cutting social contributions and de-taxing overtime hours). The Great Recession reversed this optimistic expectation. GDP growth was almost flat in 2008, and in 2009 it was shocked by a significant recession (−2.9%). However, this recession was less “Great” than in many other OECD countries, thanks to automatic stabilizers and increased public spending, which included direct support to businesses. The public budget deficit attained record highs: −7.2% in 2009 and still −5.1% in 2011. The unemployment rate basically followed the changes in GDP, even though the “Okun” effect—the short-term correlation between unemployment levels and GDP growth—was far lower than had been observed in previous decades. Unemployment jumped to 9.5% in late 2009, and then slowly declined until mid-2011.

In 2011, facing (and acceding to) EU pressure, Sarkozy's outgoing and then Francois Hollande's incoming administrations engaged in macro-adjustments [1]. More explicitly, they supported a long-term supply-side policy with massive tax reductions for firms. Despite this costly policy, the budget deficit did decline due to a freeze on civil servants’ nominal wages, the non-replacement of retired teachers, cuts in public investment, and the upsurge in direct and indirect taxes paid by households. Following these adjustments, household spending turned negative in 2012. The annual GDP growth rate was only 0.7% from 2012 to 2015. The unemployment rate increased again, reaching its peak of 10.5% in the second quarter of 2015. Eventually, business investment recovered, and a GDP growth rate above 1% in the presence of standstill productivity was associated with a new decline in overall unemployment. The unemployment rate dropping back to single digits coincided with the acceleration of annual GDP growth, about 2% from 2017 to 2019. These changes were consistent with the view that the French unemployment rate had a large component linked to a significant GDP gap.

Despite these gains, much evidence demonstrates undeniable difficulties, while at the same time highlighting strengths in the French labor market. Long-term unemployment (more than 12 months) is among the most worrying problems. From 2008 to late 2016 long-term unemployment exhibited an increasing trend. At the eve of the Covid-19 crisis, it still affected almost one out of every two unemployed workers (one out of three, according to the new definition, see Figure 1), and is a symptom of several growing divides in the labor market.

The Covid-19 crisis does not alter this picture. As in many countries, restrictions brought major sectors to a standstill. The quoi qu’il en coûte—whatever the cost—policy included giant furlough schemes (one-third of total employees at its peak), financial support for the self-employed, and direct transfers to businesses. This strategy along with credits guaranteed by the state and the closure of trade tribunals has driven a collapse in the number of bankruptcies. Workers in permanent jobs have thus enjoyed unprecedented stability. By contrast, GDP and short-term employment have faced considerable quarterly variations with uneven consequences across the country. Especially, the timing of the pandemic dictated the opportunities of seasonal workers in the large French tourist sector: exceptional activity on the western coast during the summers of 2020–2021, but job carnage in the eastern ski resorts in winter 2021.

Spatial and age divides

While most of such local impacts of the crisis will vanish in the medium term, many territories still bear scars left by the Great Recession—which accelerated the contraction of the manufacturing sector—and by the restructuring of public services associated with a reduction in public investment. At the same time, workers in these areas face greater obstacles to mobility. In particular, the areas in which job opportunities are concentrated are characterized by dramatic shortages in the availability of housing due to a scarcity of affordable properties and high prices (which only declined slightly in 2009 and 2020, and in both cases then quickly recovered). In Paris, for example, by early 2021 housing prices were 400% above their value at the beginning of the century! At this stage, the potential permanent jump of teleworking does not seem likely to alter this trend significantly.

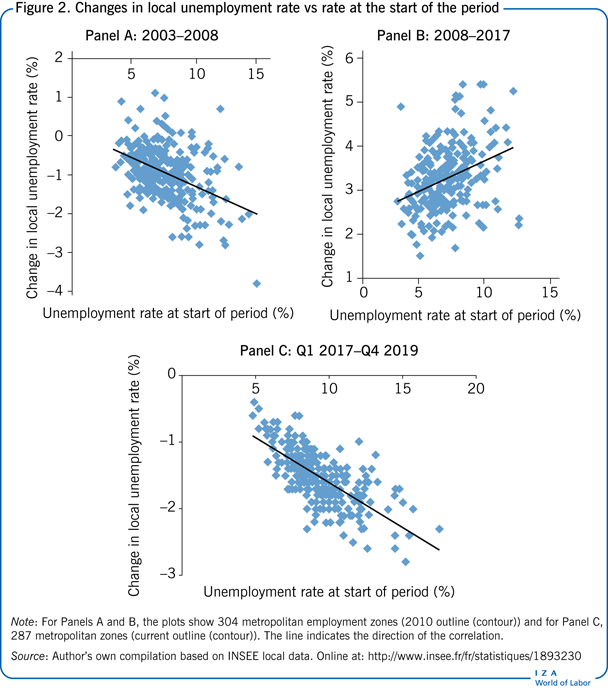

The evolution of the unemployment rate before compared to after the Great Recession versus initial levels in 2003 compared to 2008 is shown in Panel A compared to Panel B of Figure 2. Spatial heterogeneity in the unemployment rate underwent a dramatic U-turn in 2008. Although unemployment grew in all employment zones (including Paris, where it rose by 1.6 percentage points), the increase in unemployment between 2008 and 2017 was positively correlated with the initial level of unemployment. In the last legislative elections of 2017, electors in the two metropolitan zones that experienced the worst deterioration (+5.3 percentage points from 2008 to 2017) elected a leader of the far-right party (in Perpignan) and a Corsican nationalist (in Porto-Vecchio). This trend was spectacularly reversed in just three years, amid timid economic recovery (Panel C): the unemployment rate dropped in all employment zones and the spatial heterogeneity returned in 2019 to its 2003 level, still high compared to 2008. Preliminary data suggest that the Covid-19 crisis has not changed this picture, since its spatial impact was unrelated to the initial state of the local labor markets.

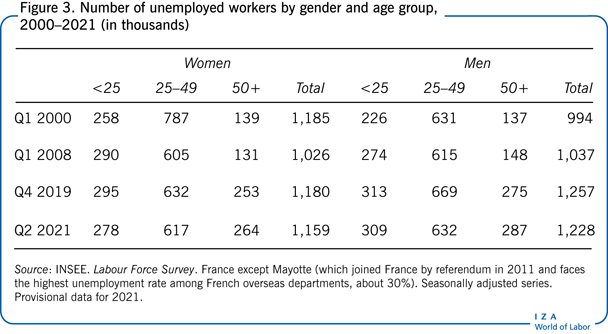

The Great Recession also changed the structure of unemployment, as many laid-off workers eventually fell into long-term unemployment; the improvement of the labor market from 2017 to early 2020 was associated with a significant decline in the number of long-term unemployed, although the number is still much higher than in 2008. A second category that partially overlapped with the long-term unemployed is aging workers, notably the less educated among them. Public pre-retirement schemes were removed in the early 2000s. From the 1970s to the 1990s, these schemes had made it possible for the economy to absorb a large proportion of blue-collar workers older than 50 who lost their jobs, especially during downturns. At the same time, progressive pension reforms initiated since 1993 provided strong incentives to lengthen professional careers. Despite these policy changes, before 2008 the increasing participation of workers older than 50—an increase of 4 percentage points for the 50–64 age group from 2000 to 2008—was quite easily absorbed. The number of unemployed workers by age group and gender is reported in Figure 3. For workers aged 50 and older it was consistently well below 400,000 until the Great Recession.

Since 2009, all age and gender groups have been affected by the deteriorating labor market, but the divide between age groups has widened. In particular, the number of unemployed female workers aged 50 or older doubled from early 2008 to early 2017, with no clear improvements since then. Although older workers still enjoyed a significant improvement of their employment rate, this trend was not sufficient to compensate for a jump in the number of participants in the labor market among the 50–64 age group (2.1 million additional participants between 2008 and 2020).

Figure 3 also shows that there is no longer a significant unemployment gap between women and men, despite the Great Recession and the Covid-19 crisis. The relatively good performance of women younger than 50 is partially explained by the fact that they benefited more from the remarkable educational upgrading of the French workforce during the past three decades.

Workforce composition and the employment rate

A much more educated workforce

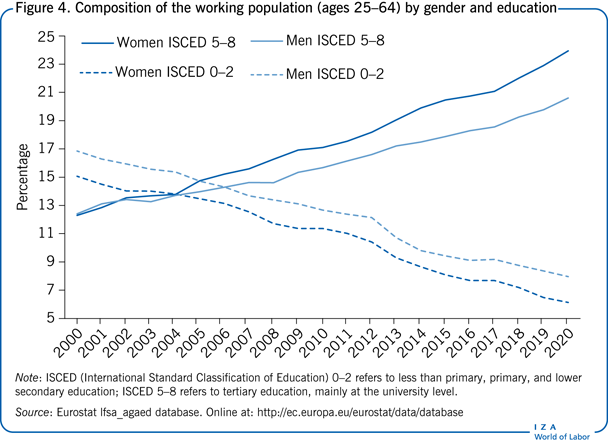

The substantial upgrading of the workforce's educational levels is probably the most impressive structural change on the supply side of the French labor market. In the wake of the agenda initiated by François Mitterrand, children born since mid-1975 enjoyed a rapid opening up of access to high school in the 1980s, to some college studies in the 1990s, and then to college graduation in the 2000s. Figure 4 shows that the share of tertiary-educated workers among the working population in the 25–64 age group has exhibited a continuous upward trend, from 25% in 2000 to 45% in 2020! By contrast, poorly educated cohorts have left the labor market during this period. Since 2005, there are fewer people in the labor market with less than lower secondary education than there are workers with a tertiary education.

Another striking fact is that a clear majority of active tertiary-educated people are now women, a mirror of the larger proportion of young women engaged in postsecondary education. The entry into the labor market of the first children of the so-called little baby boom (since the end of the 1990s) was expected to feed these trends in the two subsequent decades. Here is the main adverse impact of the Covid-19 crisis. Education at all levels from secondary school to university was dramatically disrupted for a full academic year. If the apprenticeship system survives it is thanks to massive public support; most students were unable to get internships. A large proportion of students lost their working income (in restaurants and so on) and fell into poverty, reducing their ability to engage in longer-term studies over the next several years. This raises deep concerns about the risk of a decline in the educational/training capital of this generation, at least of those young people from modest social backgrounds.

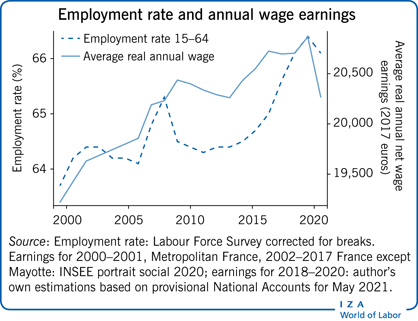

Education matters more for getting a job

Due to the upgraded educational attainment of the working-age population, France enjoys an employment rate among the active population aged 15 to 64 that is higher than in the early 2000s. The aggregated impact of the Great Recession has practically been erased, as the Illustration shows. However, it is too early to appreciate the eventual impact of the Covid-19 crisis.

According to the Labour Force Survey, despite the massive increase in the supply of highly educated workers, their employment rate has remained flat since 2000 at about 84% for the 25–64 age group. Even the Great Recession did not affect it significantly, and the 86% rate in 2019 was the highest level since World War II. It was still 85% in 2020, despite the Covid-19 crisis.

This performance contrasts with the harsh impact of the 2009 recession on less-educated workers. The employment rate of those with less than a secondary education in the 15–64 age group was stable at about 46% from 2000 to 2008, but dropped to stabilize again at around 39% from 2016 to 2020. The employment rate of secondary-educated workers slightly declined from 69% in 2008 to about 65/66% from 2016 to 2020. These trends also explain the progressive closing of the gender gap in employment rates: from 14% in 2000 to roughly 6% today.

Wage developments: Conflicting trends

Flat wage inequality?

Using exhaustive logs from employers, the INSEE computes the distribution of the full-time equivalent (FTE) salary in France. Most inequality indexes based on these French statistics follow a U-shaped curve, with a minimum in 2008. However, the magnitude of the changes is very small. For example, the 50/10 ratio, comparing the median to the bottom decile of the FTE distribution, was 1.50 in 2000, 1.46 in 2008, and 1.48 in 2018. And, by contrast with observations in many countries, the 90/50 ratio, which compares the top decile of the FTE distribution to the median, does not exhibit significant growth in France (1.99 in 2000, 2.02 in 2018). However, this remarkable stability is misleading. The focus on the disaggregated dimensions of wage inequality reveals significant changes with opposite impacts.

The declining public–private and gender gaps

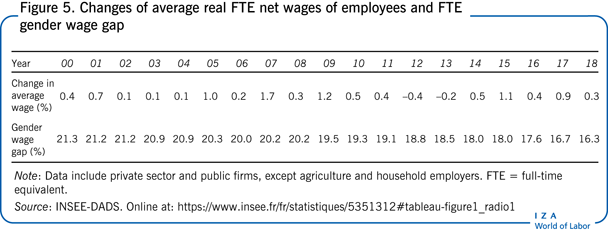

Figure 5 shows the evolution of average real FTE net wages in the private sector and in public firms from 2002 to 2014. They generally followed labor productivity rates, but did not mirror the business cycle, since they enjoyed growth in 2009 but dropped off during the start of the recovery. The apparent wage dynamics at the heart of the recession fueled the idea that French workers preferred wages rather than employment; the low wage growth since 2010 is less consistent with this naïve interpretation of the French unemployment drama.

This timing is partially explained by initial increases in nominal industry minimum wages (intended to compensate for the surge in inflation in 2008). However, the main drivers are composition effects; when the contraction of low-paid jobs in 2009 is controlled for, the average real net FTE wage is flat.

Because of the large share of skilled jobs in the public sector (teachers, doctors, and so on), there was a significant gap in earnings between public employees and workers in the private sector and public firms. However, the freeze on nominal compensation for public employees instituted in 2010 has closed this gap in recent years; from 2014, the average FTE annual wages of private workers had even become slightly larger. Since the majority of public sector employees are women, this freeze has been biased against women. By contrast, the rising relative educational attainment of women and their ability to get more skilled jobs in private firms has favored them [2]: one-third of managers are now women. The gender wage gap has been declining since the turn of the century (Figure 5), although it remains significant. In terms of annual earnings (not corrected for working time), the gender gap was still 28% in 2018.

Time-sliced salaried job contracts

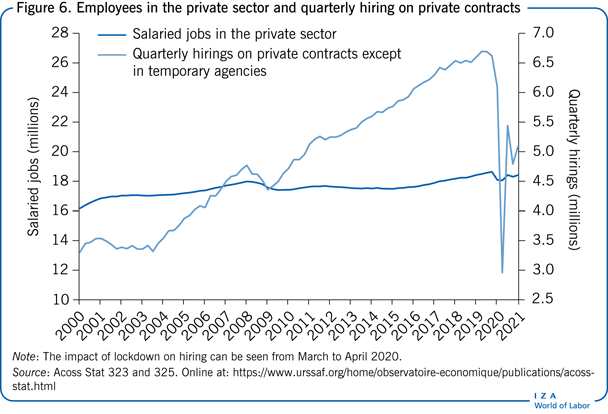

Over the past 15 years, the simplification of legal requirements and the digitization of the recruitment process have caused rapid growth in hiring in France (Figure 6). The number of newly hired workers is now greater than the stock of employees. Before the Covid-19 restrictions, each quarter, hotels and restaurants hired as many workers as the number of salaried positions.

This phenomenon is fueled by the human resources (HR) strategy of replacing long fixed-term contracts with very short contracts—most lasting less than a week—for the purpose of just-in-time adaptation of the workforce. The share of fixed-term jobs has remained steady since 2000, in contrast to the 1980s and 1990s when it was increasing [3], around 15% of total salaried employment. However, the duration of the contracts has shortened dramatically. Only one in five short-term contracts is for a month or longer, compared to two in five in 2000; the median duration is now about eight days. Another essential characteristic of this change is that most workers hired are the same people who are simply being rehired for the same job. Workers on very-short-term contracts are excluded from a variety of additional types of compensation set by industry or firm-level agreements, including annual or seniority bonuses. The shift in job quality is particularly noticeable for young (male) workers. According to the Génération surveys, in 2003, five years after completing full-time education, a large majority of men (59%) were employed in a permanent full-time job. This proportion dropped to only 37% in 2015.

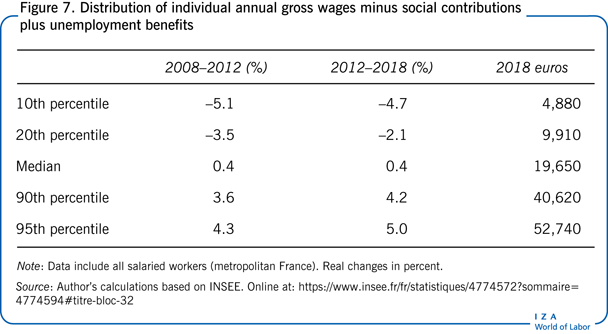

Even during the pandemic, millions of workers who are younger and less skilled moved from unemployment to employment and back to unemployment at a high frequency. This created a new form of underemployment. Slicing work contracts into ever shorter intervals reduces annual earnings at the bottom of the distribution, and the 10th percentile of the labor earnings distribution now falls far below the poverty line. The new working poor convinced unions and employers’ organizations, which manage unemployment insurance in France, to improve unemployment benefits. From this perspective, the relevant measure of labor income has come to include not just salaries, but also unemployment benefits. This improvement in benefits had first stabilized earnings at the bottom of the distribution, but it was unable to prevent the ongoing sharp decline (Figure 7).

Note that the Labour Force Survey, which uses the ILO's definition of an unemployed person, cannot capture unemployment periods within a single week. This partially explains why job seekers registered at French job centers (Pôle Emploi) are now far more numerous than unemployed people: mid 2021, Pôle Emploi recorded about 5.7 million job seekers (who had not worked during the month or had worked only partially), compared to “only” 2.4 million unemployed persons in official ILO-type statistics.

The new independent contractors

The changing nature of self-employment is another massive change in the French labor market, and it occurred over just one decade. Traditional skilled artisans have been squeezed by the recession and by competition from new entrepreneurs. In 2009, the government introduced auto-entrepreneur status—now called micro-entrepreneur status. It is now possible to become a micro-entrepreneur in just five minutes via the internet. Micro-entrepreneurs’ social contributions and income taxes are low and proportional to earnings, which can be declared on the internet each quarter, provided they are below certain turnover thresholds; but their social protection (health, pension) is basic, and most cannot access unemployment benefits. Most of these entrepreneurs do not have to charge a value-added tax, and they can also offer lower prices because they are not subject to many requirements (e.g. professional insurance) imposed on traditional artisans. As the number of classic artisans declined over the past decade, the number of independent contractors grew. However, their real revenue per hour worked dropped by around 15% on average by 2014. A new category of working poor emerged: in 2014, the 500,000 micro-entrepreneurs who were active and who did not supplement their independent activity with salary income, earned on average less than €500 a month. The emergence of the gig economy accelerated the development of micro-entrepreneurship, raising the risk of a shift from salaried jobs—including high-skilled employment—toward independent contracting. This last phenomenon has remained limited, and progressively, the new generation of independent contractors was able to build a clientele or to diversify their activities.

During the last quarter of 2019, the average turnover of the 920,000 active micro-entrepreneurs reached €4,300. The Covid-19 crisis then had dramatic consequences. Households delayed in-house activities (from music teaching to painting), while their consumption of delivery services dramatically expanded. Young workers who lost their short-term jobs, and recent (legal or illegal) migrants, have rushed on these opportunities in the so-called “economy of the last kilometer.” Preliminary figures suggest both a jump in the number of micro-entrepreneurs and a drop in their mean income.

Limitations and gaps

The interplay between the developments of independent contractors and of very-short-term jobs is not yet well captured by the current surveys or administrative data. For example, do gig jobs provide complementary income to workers on time-sliced salaried contracts, or not? In terms of welfare, an important question is whether these evolutions reflect workers’ aspirations. Another key question is whether the gig economy provides new decent opportunities to sub-populations that are discriminated against.

Much evidence, including random testing, suggests massive discrimination in the labor market against people with African or non-identifiable (by the employers) backgrounds, or those living in deprived areas perceived as having high concentrations of criminals or people unwilling to work. Even large companies with inclusive policies and trade unions discriminate [4]. There is also evidence that these populations face discrimination in the housing market (e.g. [5]), as well as in gaining access to credit for entrepreneurship through private banks and public funding. However, only a few scattered studies, and no comprehensive review, exist, since the collection of race and ethnicity statistics is strictly limited in France (a ban that remains following the exploitation of such information by the collaborationist government during World War II).

Summary and policy advice

There is no consensus among French economists on the most effective strategy for tackling mass unemployment and underemployment in France today, amid the massive improvement of the education of the working population. On the one hand, some scholars support reforms that cut employment protection legislation and benefits and extend opting out from industry agreements, in line with recommendations repeated by the IMF and the European Commission since the 1990s.

On the other hand, other academics question the relevance of these arguments, stressing the weight of the macroeconomic environment and the risk of increasing inequality. In line with the latter view, revamping the code du travail is at best a secondary issue compared to discrimination in the labor market and to more recent challenges, such as the housing shortage or plummeting public investment in depressed areas, and now the risk of a generation lost to the Covid-19 crisis.

President Emmanuel Macron received recommendations and press support from many economists in the first group. He implemented policies such as the primacy of firm-level agreements and the binding maxima for workers’ compensation that courts may award in the case of wrongful termination. The Covid-19 crisis and the exceptional macro policies make it difficult to draw clear assessments of these complex natural experiments. By contrast, much would be learned from the major aim to tackle short-term jobs. Benefits for precarious workers should be slashed: about one million would lose on average €150 per month. The theoretical argument is that these jobs are too attractive for workers, since they enjoy benefits between two working periods. The reform was imposed by government order to placate the social partners that usually set the unemployment schemes. Following the arguments of unions (and of economists of the second group), the reform was first suspended in June 2021 by the interim justice of the Conseil d’Etat (supreme administrative court), because it “will significantly penalize employees who suffer more than they choose from the alternation between periods of work and periods of inactivity […].” This reform eventually came into force in late 2021 but fundamentally provides an additional illustration of the conflicting views about the basic mechanisms of the French labor market.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the IZA World of Labor editors for helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the text and figures to 2021, including the effects of Covid-19 on the labor market.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Philippe Askenazy