Elevator pitch

Women are more likely than men to work in the informal sector and to drop out of the labor force for a time, such as after childbirth, and to be impeded by social norms from working in the formal sector. This work pattern undermines productivity, increases women's vulnerability to income shocks, and impairs their ability to save for old age. Many developing countries have introduced social protection programs to protect poor people from social and economic risks, but despite women's often greater need, the programs are generally less accessible to women than to men.

Key findings

Pros

Social protection programs designed with women in mind have reached even very vulnerable and marginalized women.

Employment guarantee programs can be made more attractive to women by offering work close to home, flexible work hours, and childcare.

Flexible eligibility requirements, child credits, and the use of unisex mortality tables improve some of the gender inequities in traditional pension schemes.

Micro-pension schemes that allow small, flexible contributions enable women working in the informal sector to save for old age.

Microfinance institutions have made it easier for women to use financial services, making saving or borrowing an ex post form of social protection.

Cons

Women’s reproductive role and social norms exclude many women from formal social protection programs.

Scaling up informal, community-level social protection programs for women can be difficult as the programs often rely on a network of highly motivated individuals that is difficult to replicate at scale.

Most women in the labor force are concentrated in the informal sector and so have limited access to pension schemes.

Although micro-pensions and defined contribution schemes are better value for women, these schemes place all the risk on individuals.

Many women lack access to financial markets and so find it hard to cope with income shocks.

Author's main message

Women face different risks in their daily lives than men do. Many women have difficulty accessing social protection programs, which are not devised with women in mind. Programs can be designed to reach women, however. Features that help women gain access include accommodating lower levels of literacy; allowing more flexibility in requirements for official documents, like birth and marriage certificates; providing services close to women's homes; accommodating women's family care responsibilities; and allowing small contributions and payments at flexible intervals.

Motivation

Although increasingly common in developing countries, social protection schemes often fail to adequately protect women. Among other reasons, this occurs because women are more likely to work in the informal sector, to drop out of the labor force to take care of children, and to have difficulty accessing financial services. Examining how and why women's needs for social protection differ from those of men and what schemes have successfully reached women is important for understanding how to design social protection for women. Social protection schemes designed with women in mind can mitigate the risks that undermine women's productivity and harm many aspects of their lives and households.

Discussion of pros and cons

High-income countries spend considerably more of their GDP on social protection than developing countries. Expenditure on social protection (excluding health-related expenditure) averages 17.7% of GDP in Europe, 15.2% in Japan, and 10.7% in the US. The corresponding figures for less developed regions are: 9.7% in Latin America, 5.9% in Africa, 2.7% in South Asia, and 1.4% in South-East Asia [2]. Although many countries have introduced social protection schemes that are intended to support poor people, the schemes often fail to reach very poor and marginalized groups, including many women.

Social protection for women can be divided into three categories:

Risk-reduction or prevention strategies that seek to establish an environment that lowers the likelihood of a risk occurring (pre-risk). Examples include training programs that reduce the chance of unemployment or income loss, and childcare services that enable women to enter the formal labor market and gain access to greater earning opportunities.

Risk mitigation strategies that provide some insurance against existing risks before an adverse event occurs, such as the establishment of a workplace savings and loan co-operative that can be drawn on in hard times.

Coping strategies that assist women in coping with the consequences of exposure to risk (after an adverse effect has occurred), such as transfers or loans.

The case for designing social protection for women in developing countries

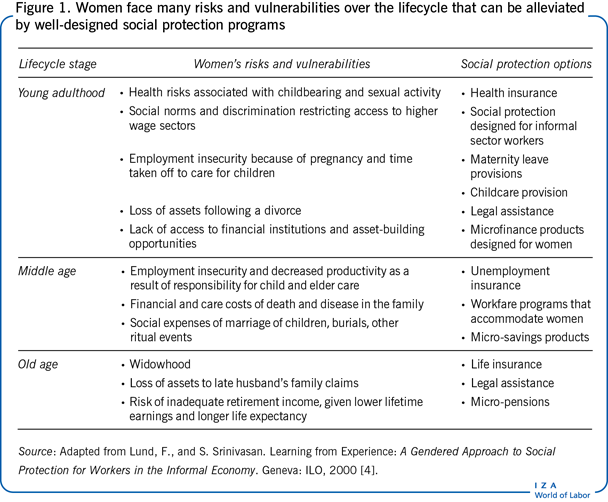

Social protection seeks to prevent, manage, and overcome risk. The risks women face in their daily lives in developing countries are shaped by differences from men in biological attributes and social norms [3] and by differences over the lifecycle [4] (Figure 1). These differences mean that the characteristics of schemes designed for men are often unsuitable for women. Equality of access to social protection thus requires programs that reflect the different nature of women's work and the different risks they face.

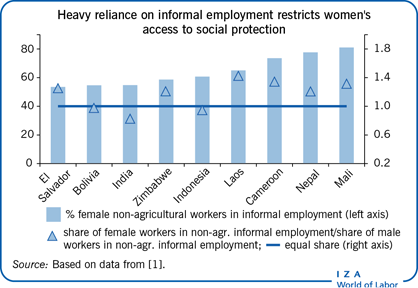

Many women are under-represented in the formal labor market because child-rearing and other household responsibilities interrupt their labor force participation, while societal norms result in labor market discrimination. In low- and middle-income countries, a higher proportion of women are in informal employment than men. Women are more exposed to informal employment in more than 90% of sub-Saharan African countries, 89% of countries in South Asia, and 75% of Latin American countries. The nature of informal employment also differs by gender with women often earning a lower income and experiencing worse working conditions [1].

Pregnancy and motherhood also lead to greater job insecurity, as employers are often reluctant to hire women of child-bearing age because of the maternity-related costs they might incur and the possibility of work disruption for childbirth and child-rearing. Flexible arrangements that allow women to manage family responsibilities and work (e.g. work-based childcare, flexible working hours) are rare.

Many women work in informal, home-based jobs that provide the flexibility to work while managing a household and caring for children, but such home-based work arrangements also expose women to exploitation. Women's greater representation in the informal sector, including informal home-based work, results in lower pay and limited access to most social protection programs, which are typically designed with formal sector workers in mind.

Women's low pay and employment insecurity extend into middle age. Many women do not acquire the training and experience necessary to open up higher earnings opportunities by middle age, and women in this age bracket have often assumed other additional household roles, such as caring for elderly parents. Women's longer life expectancy exposes them to further risks in old age—widowhood and an inadequate retirement income, given their lower earnings stream. Women's longer life expectancy alone means that, other things being equal, women require more resources than men at retirement to attain the same standard of living.

Women's lack of access to social protection would be of less concern if they were better able to draw on savings or borrowing in bad times and if resources were equitably shared within households. Traditional savings and loan products are not accommodating of women's need for smaller deposits and payments given their lower incomes. Getting to bank branches can be challenging in the face of women's multiple household responsibilities. And women are often at a disadvantage in the distribution of household resources, their tenuous claim on household assets is often overshadowed by counterclaims from the husband's family after his death. Unmarried, divorced, and widowed women's ability to benefit from social protection designed for men is even more limited.

Designing social protection programs with women in mind

Overcoming women's disadvantages in access to social protection requires accomm-odating the different situation of women. Governments can design programs adapted to women. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have been found to be particularly effective in reaching women. NGOs can implement their own social protection programs. They can also fill gaps in government-provided social protection by covering under-represented groups and by providing alternatives for poor quality or inefficiently delivered government programs. And they can facilitate access to government programs through information campaigns, referral services, and assistance to women in acquiring the documentation often needed to participate in formal social protection programs.

NGO activities at the community level have been particularly effective in reaching marginalized and socially excluded women, but scaling up the programs, which are often resource-intensive and depend on a network of highly dedicated individuals, can be difficult. The challenge is to design interventions that can be scaled up to reach and positively influence a large number of women. An extensive state-implemented social protection program remains the ultimate goal.

What works? The empirical evidence

What kinds of social protection programs have successfully reached women, especially poor women and women in informal work, who stand to benefit the most from social protection? The examples here demonstrate common forms of social protection: employment guarantee schemes, pension schemes, comprehensive social protection for informal sector workers, microfinance, and cash transfers.

Employment guarantee schemes

Employment guarantee programs, common in developing countries, typically provide opportunities for unskilled laborers to work on constructing and maintaining infrastructure, such as roads and irrigation schemes. Well-designed projects set the wage slightly lower than the market wage for unskilled labor, to attract only the poorer people for whom the programs are intended. Because of the manual labor component, these projects often fail to reach women.

However, employment guarantee programs can be designed to attract more women. The most elementary way is to include work that is socially acceptable for women, for example, by reducing the manual labor component. In some parts of Africa programs with wages based on output have attracted more women because of the greater flexibility in the allocation of time. Such arrangements recognize that working a straight day can be difficult for women, who also have to attend to children and other household responsibilities. Payment in kind (food) can also be attractive to women, who are often responsible for household food security. Programs in Lesotho and Zambia that paid half of wages in food attracted more women than men [5]. Programs that make provisions for childcare also make it easier for women to participate.

India's Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), which guarantees 100 days of minimum-wage unskilled labor each financial year, was designed to encourage women's participation. The Act stipulates that employment be offered within five kilometers of home, and that childcare facilities be provided. Women are also to be represented in the program's local committees. Almost half of participants are women (compared to women's 35% share in the rural workforce) [6].

Pension and micro-pension schemes

Standard pension schemes are typically available only in the formal sector and are still sparse in most developing countries. For the pension schemes that do exist, there has been a shift (encouraged by international institutions such as the World Bank) from pay-as-you-go schemes to either defined benefit schemes, with pension payments based on earnings and job tenure, or defined contribution schemes, with payments determined by the level of individual contributions and the returns on these contributions.

Although women's lower earning capacity generally results in lower contributions, women tend to be better off under defined contribution than defined benefit schemes. Defined contribution schemes are portable and depend only on the amount and timing of contributions. Defined benefit payments are based on final salary and tenure, thus implicitly redistributing benefits from short-tenured, low-earning workers to long-tenured, higher earning workers. Because women's more variable labor force participation reduces their tenure in any one job, their capacity for salary growth and thus their final salary is lower than men’s. Women will still do worse than men under defined contribution pension systems, but the gender gap is likely to be smaller than under defined benefit systems.

The gender-equity of a pension scheme reflects: (i) the benefit formula; (ii) the vesting period (the number of years contributions need to be made to qualify for benefits); (iii) the indexation mechanism; and (iv) mandated retirement ages. Benefits that are more closely tied to earnings benefit men over women, relative to flat-rate benefits. Some pension schemes provide earnings-related benefits along with a flat-rate minimum pension guarantee (as a sort of safety net) for workers who meet certain means-testing criteria. Some explicitly compensate women for career breaks. The use of unisex mortality tables that do not penalise women for their longer longevity is a further female-friendly characteristic. Lengthy vesting periods make it less likely that women will qualify for a pension due to career interruptions associated with caring responsibilities. Adequate indexation of benefits is also particularly important for women as they spend a longer period in retirement. Earlier retirement ages for women also adversely affect the pension gender gap as women have a shorter time to accumulate assets in a defined contribution scheme [7].

Chile and Bolivia have redesigned their pension schemes to incorporate many of these female-friendly aspects. Chile's national pension scheme is a contributory scheme but incorporates a flat-rate pension for elderly people from low-income families with no other pension income and a top-up payment for members with low contributory pensions. It has no minimum requirement in terms of years of contributions to receive benefits, provides child credits equivalent to 18 months of contributions at the minimum wage for each child (plus interest calculated from the date of the child's birth), does not have fixed administration fees; allows splitting of the husband's pension in the case of divorce; and allows for female household workers to open and make voluntary payments into an account. Studies find that it provides equal access to benefits for men and women. The Bolivian pension also incorporates many of these characteristics. Although it does not allow for contributions from unpaid workers, its use of gender-neutral mortality tables does not penalize women for their longer life expectancy.

India's national pension scheme specifically seeks to serve the poor and informal sector workers (and hence women). It consists of three pillars. The first pillar is the Indira Gandhi National Old Age Pension Scheme which provides a minimal monthly payment (Rs 200, US$2.82) to the very poor aged over 65 (and which in practice has very low coverage). The second pillar, Atal Pension Yojana, is designed to reach informal sector workers. In this scheme, every contribution made by individuals to the pension fund, is matched by a 50% co-contribution from the central government or Rs 1,000 (US$14.12) per annum, whichever is lower, for a period of five years. All workers who subscribe before the age of 40 are eligible for pensions of up to Rs 5,000 (US$70.61) per month after turning 60 [8]. The third pillar of India's pension scheme relies on private contributions, which can be in the form of micro-pensions, which encourage informal sector workers to save towards retirement.

A prominent example of a micro-pension in the context of India is UTI's micro-pension scheme. UTI is a publicly owned mutual fund. Its micro-pension scheme accepts very small, voluntary deposits at flexible intervals, with no entry charges. Contributions must be paid until age 55, and pension payments begin after age 58. A 1% charge is applied to balances withdrawn before the stipulated retirement age. UTI works with third parties—cooperatives, microfinance institutions, or NGOs—whose job it is to attract large numbers of members with shared characteristics, to channel communications between members and UTI, and to conduct administrative functions. This partnership lowers the cost of account servicing and customer acquisition, which helps make the scheme viable despite the low value of individual accounts [9].

Pension schemes elsewhere in the Asian region score poorly in terms of gender equity. Social pensions for low-income individuals are rare in South-East Asia (with the exception of Thailand) and vesting periods exceed women's average expected years of employment (Philippines, 10 years; Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam, 15 years). Credits are not offered for periods of maternity leave [10].

Several African countries provide non-contributory social pensions with levels ranging from 4% (Botswana) to 34% (Lesotho) of per capita GDP.

Comprehensive social protection for informal sector workers

Comprehensive social protection programs for informal workers are provided in some countries by the government or by worker organizations. India has many Worker Welfare Funds. These funds are set up by the (central or state) government and targeted at industries which employ many informal workers, for example, footwear workers, handloom and silk weavers. They are funded by taxes on the industry's production and provide social protection for workers in the informal economy. The Bidi Welfare Fund is one such example. Bidis are small, hand-rolled cigarettes which are produced mainly by women working from home. The Bidi Welfare Fund is funded through a bidi export tax. The funds provide medical care, education for children, housing, water supply, and recreational facilities.

The state of Kerala has the most comprehensive set of worker welfare schemes in India. Its schemes are funded by contributions from workers, employers, and government. Benefits vary but commonly include pension and retirement benefits, disability allowances, funeral expenses, education benefits, medical care, marriage and maternity benefits, unemployment benefits, and housing loans. Similar funds have been established in other countries, including Thailand.

An example of non-government provision of comprehensive social protection for informal sector workers is the insurance provided through India's Self-Employed Women's Association (SEWA), a trade union of self-employed women with more than two million members across ten Indian states. Established in Gujarat state in 1972, SEWA has its own bank, cooperatives, and health initiatives, and in 1992 it set up a simple life insurance scheme which paid a benefit of Rs 3,000 (US$42.37) to the husband of a SEWA member on her death or after permanent disability. This has since been expanded into an integrated insurance scheme that for an annual payment of about Rs 60 (US$0.85) (or the accumulation of interest on a Rs 500 (US$7.06) fixed deposit with SEWA Bank, which is accumulated through fixed monthly instalments of Rs 20 (US$0.28)) offers life insurance, health insurance covering hospitalization costs, asset and loan insurance, as well as a fixed-sum maternity benefit for each pregnancy, to more than 30,000 members. SEWA health workers collect claims in the villages, discuss the claims with the doctor, forward them to SEWA Bank, and disburse the payments to the women in the villages. Health workers also publicize the insurance program and sign up new members.

SEWA originally acted as an intermediary between national financial institutions and SEWA's large membership of self-employed women. Dealing with SEWA rather than directly with hundreds of thousands of individuals made it feasible for the institutions to offer their services to SEWA's members. SEWA, however, gradually built up its technical skills and funds (with the help of a US$350,000 grant from the German Society for International Cooperation (GTZ)), and shifted from being an intermediary to being a direct provider of loans and insurance to its members [11].

Microfinance

Because savings and credit can help people get through bad times, access to financial services is a form of social protection. Women are often excluded from financial services for a variety of reasons, including low levels of literacy, lack of necessary documents and collateral, and difficulty reaching bank branches. Although recent reviews of the research literature suggest that microfinance has not had the transformative ability that some expected, microcredit has been found to have a modest positive impact on incomes, particularly when combined with skill development programs.

In Bangladesh the Income Generation for Vulnerable Group Development (IGVGD) program has demonstrated that it is possible to provide access to microfinance services for very poor women. The program arose out of a pilot implemented by BRAC, a large Bangladeshi NGO. It is now implemented by the Ministry of Women and Children's Affairs, in partnership with the Ministry of Food, BRAC, the United Nations World Food Programme, and a large number of other NGOs. Some two million women have accessed microfinance services through the program. The program targets destitute women who have few or no income-earning opportunities. It combines a food security component with skill development and microcredit. Areas are identified on the basis of food insecurity and vulnerability maps. Community committees with female representatives assist in selecting beneficiaries. Each participant is expected to save at least 25 taka (US$0.30) a month. Participants meet weekly with 25−30 members of BRAC's microfinance program. The groups provide a forum for discussion and mentoring on legal and social issues and small-scale enterprise challenges, and training on income-generating activities that require low initial capital outlays, such as poultry rearing. After six months of training, participants receive the first of two loans to start a small business. They are expected to supplement these loans with their accumulated savings. An important component of the program is that participants also receive 30 kg of rice or 25 kg of fortified flour for an 18-month period which provides them with food security for this period. Loans are repaid over 45 instalments, so that by the end of the cycle of food transfers, most participants will have paid off their first loan and have received their second. By the end of the full program, participants should be in a position to access and use mainstream microfinance services.

Impact assessments found modest increases in income, a decline in begging, some savings, increased asset ownership, and improvements in social status. Two-thirds of program participants graduated to mainstream microfinance programs [12].

Conditional and unconditional cash transfers

Conditional cash transfers provide cash payments to participants, normally to women, who meet a number of explicit criteria. The conditions typically concern children's school enrollment and attendance at preventive and reproductive health clinics. Payments in these programs are generally made to mothers because of evidence that women tend to invest more in children than men do. There is an ongoing debate as to the need for conditions to be attached to the transfers. Both conditional cash transfers (popular in Latin America) and unconditional cash transfers targeted at women (more popular in sub-Saharan Africa), such as Zambia's Child Grant Programme, have been shown to increase women's ability to save and hence cope with income shocks.

Limitations and gaps

Although there have been many high-quality impact evaluation studies of social protection programs, few studies have compared programs designed specifically for women with programs without gender-sensitive designs, and few have evaluated holistic approaches to social protection for women, such as SEWA's integrated insurance scheme. Thus the empirical evidence presented here relies mainly on case studies and qualitative, descriptive evaluations rather than experimental design studies that can assess causal impacts.

Summary and policy advice

Social protection schemes often fail to adequately protect women. Examining how women's needs for social protection differ from those of men and what schemes have successfully reached women is important for understanding how to design social protection for women. Women are more likely than men to work in the informal sector and to drop out of the labor force for a time, such as after childbirth or because of social norms, so their needs can often be greater than those of men. This combination of factors undermines productivity, increases women's vulnerability to income shocks, and makes it harder for women to save for old age.

To reach women and mitigate these risks, social protection programs need to reflect the features of women's daily lives. Employment schemes need to offer flexible work times, services within easy reach of home, and assistance with child and elder care. Pension vesting periods and contribution conditions need to be dropped or lowered. Low levels of literacy need to be accommodated, and documentation requirements eased. NGOs are often well placed to harness local knowledge and are able to design projects to reach the most vulnerable women and which reflect local needs. To learn more about how to reach women and the kinds of programs that are effective, studies need to compare the reach and impact of programs designed specifically for women with more traditional programs.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the Illustration, revises the “Pros,” extensively updates the research in the text, and fully revises the reference lists.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Lisa A. Cameron

Social protection schemes

- Unemployment insurance

- Maternity leave and employment protection during pregnancy and post-delivery

- Childcare and other social support services

- Health coverage and insurance

- Life and disability insurance

- Pension schemes

- Interventions to enhance access to financial services