Elevator pitch

Income inequality is a critical issue in both political and public debate. Educational attainment is a key causal factor of continuing inequality, since it influences human capital accumulation and, as a consequence, the unequal distribution of earnings. Educational inequality displays a racial dimension that is particularly persistent and difficult to eradicate through policy measures. Its roots lie in the colonial institution of slave labor, which was widespread in the US and Latin America up until the 19th century. However, the influence of slavery differs significantly across countries and between regions.

Key findings

Pros

There is empirical evidence that shows a negative relationship between slavery and current educational outcomes.

Racial education inequality has been closing over time but is still persistent.

Racial education inequality can be traced to the legacy of colonial slavery.

Colonial slavery affects current income inequality and its racial component via the channel of education.

Cons

Evidence on the relationship between slavery and current educational outcomes is rich for the US but less so for other regions.

Latin America is characterized by persistent income and educational inequalities, but country experiences differ with respect to historical slavery.

Slavery can be associated with a lower level of education; but evidence on its differential effect across races is scarce.

The influence of additional institutional factors (development of mass education and a more assimilationist approach to the integration of former slaves) can limit the effect of slavery on inequality.

Author's main message

Evidence suggests that in some countries historical slavery has influenced the racial distribution of human capital and income inequality. A regional comparison of the influence of slavery on education, racial education inequality, and income distribution shows that policies aimed at addressing inequality can account for differential effects of past slavery on current outcomes. Policies designed to remove racial education inequalities in schools can favor income equalization, though given the resilience of the effect of past slavery they are by no means an immediate solution. Nevertheless, education policy clearly has a strong influence over time.

Motivation

The possible links between the institution of slave labor and contemporary educational outcomes and income inequality is a focus of much political and public debate, with racial considerations being central to the discussions. In order to gain a better understanding of these issues, it is important to consider the available evidence on the impact of racial differences in education to overall differences in income.

In those countries that have historically experienced slavery, inequality in terms of education and income currently demonstrates a strong racial component. This calls into question the possible effects of slavery on racial inequality. In particular, whether slavery has influenced the accumulation of human capital and its unequal distribution across racial groups. While slavery has been widespread all over the world for thousands of years, an analysis of the historical experience of slavery in the Americas following the trans-Atlantic slave trade is particularly informative. Documenting the evolution of racial education inequality in the US, its link with past slavery, and its implications for income inequality reveals a clear relationship between past slavery and contemporary education inequality across races, both in terms of the quality and the degree of education.

However, evidence from Latin America and the Caribbean highlights that there are regional differences in the relationship between slavery, education, and income inequality. These differences are potentially due to institutional factors. For example, African slavery in this region was accompanied by local forms of labor coercion. In addition, mass education developed more slowly. Finally, in Latin America and the Caribbean the white colonists opted for a culture of assimilation that led over time to widespread racial mixing. In contrast the US developed, up to a point, a segregated society in which black people still maintain a strong racial identity even to the present day.

A regional comparison reveals that policies aimed at addressing inequality can account for the differential effects of past slavery on current outcomes, with the educational channel clearly emerging as a very strong influence.

Discussion of pros and cons

The US

Evidence on human capital accumulation by race

The economic literature on racial inequality in education in the US is extensive [2], [3]. The evidence documents the evolution of racial differences, both in the quality and the quantity of education. Following the American Civil War, African Americans had essentially no exposure to formal schooling. This was a legacy of the extremely high rates of illiteracy that prevailed in the southern plantations, where the vast majority of African Americans were employed. The next generations of the descendants from African slaves, initially still located mostly in the south, were able to complete far fewer years of schooling than white people. They also had access to racially segregated public schools, which provided a qualitatively inferior education in comparison to what was available to white people [4]. By 1940, as a result of the combination of low educational attainment and inferior educational quality, the racial gap was still very wide. Subsequently, however, as successive generations of black children received more and better schooling, the racial gap narrowed, with an eventual impact on earnings equalization.

Persistence of racial education inequality

Overall, the evidence on the evolution of racial educational differences points to long-term convergence, but also to the persistence of disparities along racial lines [4]. This takes into account a wide number of dimensions, such as literacy rates, years of educational attainment, spending per pupil and returns to literacy.

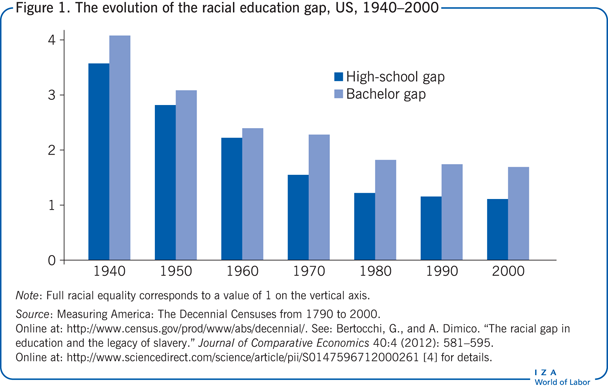

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the racial gap, at the high school and the bachelor level, from 1940 to 2000. For each year, the histograms represent the ratio between the share of white and black people, in the corresponding populations, holding at least a high school or a bachelor degree. Full racial equality would correspond to a value of one on the vertical axis. However, starting for instance from the first histogram, it reveals that in 1940 the share of white people with a high school education is between three and four times the corresponding share of black people.

Overall, the figure shows that over the 1940–2000 period, white people are on average more educated than black people at both levels. The gap is even larger at the bachelor level. Over time, the gap decreases for both levels, but at a lower rate for the bachelor level. The decline of the gap is much more marked up to 1980, while progress has been much slower since then. Despite its gradual reduction, the gap is still present until the end of the period: in 2000 the ratio is still above one for high school degree and almost two for the bachelor degree. These trends confirm the persistence of deeply-rooted racial disparities, despite the presence of a convergence process.

Slavery and racial education inequality

The institution of slavery is highly likely to be a factor conditioning race relations and, in particular, racial inequality along multiple dimensions, including human capital and education. The historiography of slavery in the US is also extensive. In the aftermath of the American Civil War the legacies of slavery determined extremely high rates of illiteracy among black people. The obstacles subsequently encountered by black children in acquiring education are widely believed to represent the channel through which inequalities were perpetuated.

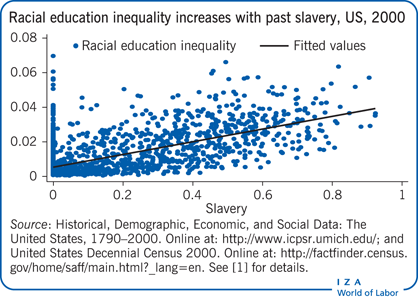

The correlation between the racial educational gap in 1940 and the share of slaves over population in 1860 is extremely high: 0.90 and 0.81 at the high school and bachelor level, respectively. For the state-level data (Illustration), empirical estimates of the determinants of racial educational inequality during the period 1940–2000 confirm a causal effect of historical slavery. This effect continues through from its influence on the initial gap, both at the high school and bachelor level [4]. In other words, those states that relied more intensively on the use of slave labor in 1860 still exhibited larger contemporary racial disparities in education in 2000, through a channel that is represented by the initial gap in attainment.

The transmission of human capital is therefore the link between slavery and current racial gaps in schooling attainment, which confirms that the origins of educational inequality are indeed very deeply rooted in the history of this country [1], [4].

Channels of transmission

What is driving the correlation between slavery and education is the local nature of schooling provision and funding, in conjunction with the political exclusion of the descendants of African slaves, at least up to the 1960s. Indeed in the former slave states in the US black people have been persistently disenfranchised, both through de jure and de facto methods.

The property tax is the principal source of local funding and therefore for public educational support. Under the “Separate but Equal” educational policies applied in southern states until the 1960s, local officers could divert state funding for black people in order to subsidize education for white people. As a result, they could impose a lower property tax and spend less on the overall education budget. Even after legally mandated school segregation was abolished, the counties that had previously chosen low education expenditures adhered to a lower tax rate, with negative effects on public school funding and, in particular, on education for black people.

Empirical evidence supports the relevance of political mechanisms for the determination of education outcomes. For example, the disenfranchisement provisions enacted following the abolition of slavery in the late 19th century in the southern states are associated with a fall in black educational inputs and with low-quality southern schooling [5]. Within the state of Mississippi, which had one of the highest proportions of slaves, there is also a significant and positive effect of black political participation in the late 19th century on contemporary black educational outcomes [6].

Implications for income distribution

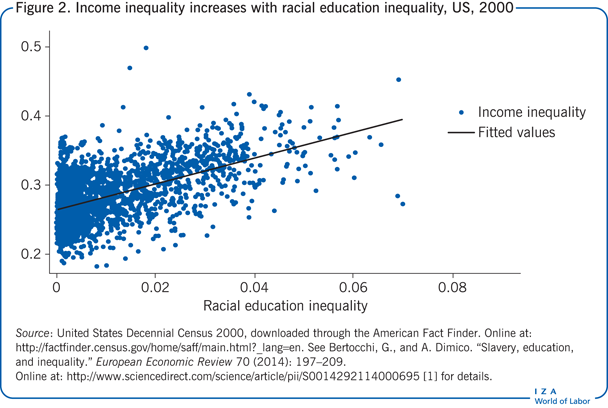

The influence of slavery on education disparities has even broader implications, since through its impact on the racial gap in human capital accumulation it, in turn, affects income inequality between races and ultimately overall income inequality. In other words, the distribution of per capita income is more unequal today in counties associated in the past with a larger proportion of slaves in the population [1]. The positive correlation between racial education inequality and income inequality is illustrated in Figure 2, which is based on cross-county census data from 2000.

Evaluation of policies

The key Supreme Court decision to overturn the “Separate but Equal” doctrine that allowed racial segregation in US schools (Brown v. Board of Education, in 1954), initiated a long process involving subsequent rulings as well as federal legislation. Since then, education policy has always been at the heart of government intervention aimed at reducing racial disparities.

In the desegregation years between the 1960s and the 1970s, substantial gains were made, with a tapering in subsequent decades. The declared goal of recent reform programs for the US schooling system has been the removal of the persistent and pervasive racial and ethnic educational gaps. This is the case both for “No Child Left Behind,” which was the federal education program enacted in 2002 under President Bush, and for “Race to the Top,” the current program created in 2010 by President Obama. Both programs have relied on the introduction of standards and assessments of students and teachers based on test scores, with a focus on special support for the worst-performing schools and on special initiatives directed at developing pre-schooling and vocational education. The emphasis put by both administrations on these programs is consistent with the evidence presented earlier. This evidence shows how deeply educational inequality is rooted in the history of the country. It still remains to be seen whether these policies can fulfill their goals and expedite the process of convergence to full equality.

Latin America

Latin America is generally characterized by extreme levels of inequality, both along the income and the educational dimensions. This makes the region highly suitable for an analysis of the influence of slavery and its potential implications for current policies.

The intensity of African slavery following the trans-Atlantic slave trade has been at least as high in Latin America and the Caribbean as in the US, albeit with marked cross-country heterogeneities. The highest intensity is found in Brazil, as well as in the Caribbean (particularly Haiti and Jamaica), while other countries, such as Bolivia, received hardly any African slaves at all. On the other hand, other forms of labor coercion, such as the mita in Peru and the libreta system in Puerto Rico, were practiced in Latin America and the nearby Caribbean during the colonial and post-colonial period. The mita was, in fact, imposed on the indigenous population rather than on the population of African descent.

An important distinction between South and Central America on the one hand and North America on the other has been the general approach to education and the development of educational systems. The US, as well as Canada, invested heavily in primary education from the very start, despite the fact that in the former there was a geographical differentiation with the predominantly black south lagging behind. On the other hand, even the richest countries in South and Central America were extremely slow in providing schooling institutions directed to mass education.

Another important distinction is that in Latin America and the Caribbean the white colonists opted for a culture of assimilation, leading over time to widespread racial mixing. While the US developed, up to a point, a segregated society where black people still maintain a strong racial identity even to the present day.

When comparing countries in Latin American and the Caribbean with the US, with respect to the slavery-education nexus, it is important to bear in mind the above distinctions with respect to the local forms of labor coercion, the approach to mass education, and the integration process.

What follow are the findings from a number of country studies that supply useful evidence in this respect, even though they focus predominantly on the influence of slavery on the amount of education rather than on its racial distribution.

Brazil

Brazil was the destination of almost half of the African slaves who were shipped across the Atlantic. African slaves sent to Brazil outnumbered those sent to the US by a ratio of about ten to one. Brazil was also the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery, which it did in 1888.

However, in part because of the custom of inter-racial marriage, slavery in Brazil never resulted in the forms of segregation that have been observed in the US. Empirical evidence on this country has uncovered a negative correlation between past slavery (proxied by measures of land inequality, which are strongly correlated with the presence of crops suitable for the use of slave labor) and quantitative and qualitative measures of contemporary education (namely, the share of the population between 15 and 17 years of age attending secondary education in 2000, and a 2005 index of school quality provided by the government) [7].

A parallel investigation, which focused on the period 1889–1930, has shown that Brazilian states with fewer slaves were able to exploit positive trade shocks and invest the resulting export tax revenues in elementary education expenditures, thus achieving higher literacy rates. An opposite, negative effect on education is observed instead, under the same circumstances, in states with more slaves. The resulting distribution of human capital across states in Brazil persists to the present day [8].

However, contrasting evidence emerges from a county-level analysis of the state of São Paulo, which is the largest state in the country. In São Paulo, the intensity of slavery shows no discernable long-term impact on a variety of current education indicators [9].

Colombia

In order to investigate the impact of slavery on long-term development in Colombia, it is possible to exploit the variation in the presence of gold mines in different municipalities, since gold mining was strongly associated with demand for slave labor. The empirical findings show that the historical presence of slavery is associated with reduced measures of various contemporary education indicators and, more generally, increased poverty and land inequality. Even though the question of racial education inequality is again not explicitly addressed, it can be observed that districts more heavily associated with slavery have higher shares of population of African descent. This suggests negative implications for the influence of slavery on the racial dimension of education inequality [10].

Puerto Rico

Even though this Caribbean country did experience African slavery, the available evidence concerns the impact of the libreta system, which was an alternative form of labor coercion introduced in 1849 following the 1845 agreement between Spain and Britain to enforce the abolition of the slave trade. This de facto substitute of slavery remained in place until 1874. Using the response to regional variation in coffee prices and demand for unskilled labor, these findings indicate that in coffee-growing regions, during the coercive period, higher coffee prices had no effect on literacy rates, whereas after the abolition of coercion higher coffee prices reduced literacy rates.

These results suggest that the abolition of forced labor reduced the incentive to accumulate human capital. However, despite appearing puzzling at first glance, they are not inconsistent with the intuition that coercive labor institutions should exert a negative influence on long-term human capital accumulation, since a side-effect of abolition was an increase in the relative wages of unskilled laborers [11].

Peru

Focusing on a segment of modern-day southern Peru that transects the Andean range, it is possible to gauge the impact of yet another form of labor coercion. The mining mita system, which was an extensive forced mining labor system, was instituted by the Spanish government in 1573 and abolished in 1812. It is worth noting however that, rather than involving black slaves, the mita system was applied to the indigenous population. Analysis has shown that the mita’s impact on education is fading through time. While a negative impact can be observed in earlier periods, by the 2000s there is no remaining evidence of a negative influence, across a range of education indicators [12].

Limitations and gaps

It should be noted that for the US, besides human capital, a parallel potential determinant of the relative improvement of the economic status of black people following the Second World War has been the civil rights revolution. This has had a significant impact on affirmative action laws and the consequent removal of racial discrimination. The evidence supporting the relevance of the racial discrimination channel is weaker than that collected for the education channel [4]. However, since racial discrimination can manifest itself not only in the labor market, but also in the school system, it is difficult to disentangle its separate influence from human capital.

For Latin America and the Caribbean, there is mixed evidence on the influence of past forms of labor coercion on contemporary education outcomes. Even when a negative influence emerges, no specific research has been produced on education inequality along the racial dimension. More research is therefore needed on the determinants of the extremely high degrees of inequality reported in this region. Past slavery is a potential factor that deserves further investigation, even though labor coercion and racial relations developed following different and heterogeneous patterns, both across the continent and in comparison with the US. More specifically, future research should clarify whether any legacy of slavery, if present, runs through the same education channel that is apparent in the US.

With regard to the other crucial link between slavery and income inequality, a correlation has been documented across a world sample of 46 countries, even though it is not clear that the influence of slavery necessarily runs through the education channel [13].

Summary and policy advice

The legacy and influence of slavery on education is not necessarily the same across different countries. In the US, there is a clear influence of historical slavery on human capital accumulation, on its racial distribution and, through this channel, on income inequality.

Even if the emerging picture suggests that racial inequality is very deeply rooted in the history of the country, it also identifies the main channel through which history exerts its continuing influence. This channel is represented by the unequal access to education of black people and white people. Policies that are targeted towards removing racial education inequalities in US schools can favor income equalization. However, given the resilience of the lingering effect of past slavery, their degree of success may be limited.

In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean, the level of inequality is even more striking. However, there is no clear evidence that this can be attributed to the history of slavery and to its influence on education and its racial distribution. This does not mean that equalizing education policies today are less needed, but simply that there may be additional factors, other than slavery, that play a more important role.

In summary, evidence suggests that in some countries historical slavery has influenced the racial distribution of human capital and income inequality. A regional comparison of the influence of slavery on education, racial education inequality, and income distribution shows that policies aimed at addressing inequality could account for differential effects of past slavery on current outcomes. Policies designed to remove racial education inequalities in schools can favor income equalization, though given the resilience of the effect of past slavery they are by no means an immediate solution. Nevertheless, education policy clearly has a strong influence over time.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author is indebted to Arcangelo Dimico, with whom she co-authored all the papers that led to this article, namely [1], [4], and [6]. Previous papers contain a larger number of background references for the material presented here and have been used intensively in all major parts of this article. Financial support for those papers from the Italian University Ministry and Fondazione Cassa Risparmio di Modena is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Graziella Bertocchi

The trans-Atlantic slave trade

For data see: Eltis, D., S. D. Behrendt, D. Richardson, and H. S. Klein. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade: A Database on CD-Rom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

For an analysis of its consequences from the perspective, respectively, of sending and receiving countries, see: Nunn, N. “The long-term effects of Africa’s slave trades.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123:1 (2008): 139–176; and Soares, R. R., J. J. Assunção, and T. F. Goulart. “A note on slavery and the roots of inequality.” Journal of Comparative Economics 40:4 (2012): 565–580.

Slavery in the US

On the history of slavery in the US see: Berlin, I. Generations of Captivity: A History of African American Slaves. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

For an economic history of American slavery see: Fogel, R. W., and S. L. Engerman. Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1974.

For further sources of information see: Bertocchi, G., and A. Dimico. “Slavery, education, and inequality.” European Economic Review 70 (2014): 197–209; and Bertocchi, G., and A. Dimico. “The racial gap in education and the legacy of slavery.” Journal of Comparative Economics 40:4 (2012): 581–595.