Elevator pitch

There is increasing global competition for high-skilled immigrants, as countries intensify efforts to attract a larger share of the world's talent pool. In this environment, high-skill immigrants are becoming increasingly selective in their choices between alternative destinations. Studies for major immigrant-receiving countries that provide evidence on the comparative economic performance of immigrant classes (skill-, kinship-, and humanitarian-based) show that skill-based immigrants perform better in the labor market. However, there are serious challenges to their economic integration, which highlights a need for complementary immigration and integration policies.

Key findings

Pros

Skill-based selection of immigrants responds to the needs of the economy.

High-skilled immigrants have better labor market prospects in general than immigrants admitted based on kinship ties or for humanitarian reasons.

High-skilled immigrants boost innovation, a key to long-term economic growth.

High-skilled immigrants in the labor market can raise wages for low-skilled native workers struggling with declining labor market prospects.

Highly paid skill-based immigrants widen the tax base and help offset growing fiscal challenges.

Cons

The design of selection systems for skill-based admissions is complicated and requires frequent updating as the economic environment changes.

Skill-based immigrants face formidable economic integration challenges due to skill and credential transferability problems and underutilization of their human capital.

Identifying short-term skill shortages as a basis for admissions is difficult and may not be in line with long-term needs of the economy.

Allocating a higher share of immigrant admissions based on skills usually comes at the expense of kinship- and humanitarian-based admissions.

Author's main message

Labor market prospects are better for skill-based immigrants than for other immigrants. However, skill-based admission is not a remedy for all the economic outcome problems of immigration, including weak economic integration. Designing skill-based selection policies is complicated; policies need to reflect labor market characteristics and the applicant pool. To maximize benefits, governments should complement immigrant selection policies with economic integration policies to ease the transfer of foreign human capital.

Motivation

Improving the economic impact of immigrants has been an important policy issue in developed countries. Immigrants are expected to contribute to economic growth by supplying needed skills and enhancing the labor force in their host countries. Policy discussions center on identifying which type of immigrant flow will maximize these expected economic benefits.

Many immigrants arrive in their destination country because of kinship ties with earlier immigrants in that country (so-called “chain-migration”). These immigrants base their immigration decisions on information received from family members in the destination country. This reduces the possibility of making bad decisions based on unrealistic or unreliable information about labor market prospects in the destination country. Kinship-based immigrants also have access to the networks of their family members, which facilitates their integration into the new country. However, working-age kinship-based immigrants tend to be less skilled than working-age native workers, which poses challenges for their economic integration.

Another group of immigrants are admitted to host countries for their skills. While immigration of low-skilled workers reduces the employment prospects and wages of low-skilled native workers, at least in the short term, the reverse is true for high-skilled immigrants, who have better employment prospects and integrate better into the economy [1]. Skilled immigrants increase the receiving country's human capital stock, boost returns on physical capital, and may spur research and innovation that increase the country's long-term economic growth prospects. Admitting high-skilled immigrants to fill short-term skill shortages in rapidly expanding skill-intensive sectors can improve industrial competitiveness and keep jobs in the country. Highly paid skill-based immigrants widen the tax base and help offset growing fiscal challenges, especially those associated with aging populations. These positive prospects help maintain public support for immigration, as opposition to immigration rises with perceptions of poor labor market performance and heavy welfare reliance.

For these reasons, attracting the best trained and most skilled workers has become an important policy objective. With the growing importance of the knowledge economy, global competition for skilled workers has also intensified. Retaining skilled workers, facilitating the return of emigrants, and attracting talent from other countries also emerged recently as a policy objective in developing countries. The need for effective policies is intensifying in this increasingly competitive environment.

Each immigrant-receiving country makes its own choices with regard to the rules of selection, and these policies play an important role in shaping the economic outcomes of immigrants. This article presents evidence on the advantages and challenges of skill-based visa systems and compares them with other systems, such as kinship-based, humanitarian-based, and temporary admissions.

Discussion of pros and cons

Visa categories and immigrant selection

There are three main visa categories for admission of permanent immigrants: (i) kinship-based; (ii) skill-based; and (iii) humanitarian-based (refugees and asylum-seekers).

Kinship-based admissions—also referred to as family reunification or family class—grant admissions to family members of existing immigrants. The skill-based class consists of individuals who are assessed for their skills and employability. Immigrants in this group are referred to as skilled workers, economy class, occupation-based, or employment-based immigrants. The refugee class admits individuals based on humanitarian grounds. Kinship- and humanitarian-based immigrants are not assessed for skills.

Besides these permanent admission categories, host countries also admit individuals on temporary visas. These include temporary workers and international students who wish to pursue their education in the host country. Some of these temporary residents later adjust their status to permanent residency either through a skill-based admission or as a family class immigrant by marrying a host country citizen or a permanent resident.

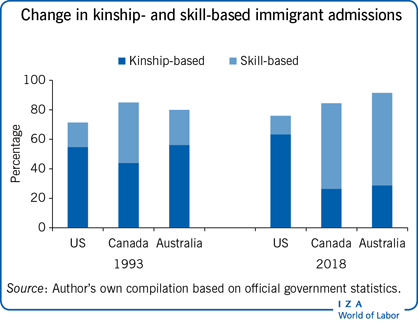

The share of skill-based admissions varies considerably across host countries. While Australia, Canada, and New Zealand admit the majority of immigrants based on skill requirements, the fractions of skill-based admissions in the UK and the US are much lower.

Over time, substantial changes are observed in receiving countries in the composition of permanent immigrants by immigrant class, reflecting immigration policies’ changing priorities. Since the early 1990s, the share of skill-based admissions among immigrants has risen sharply in Australia and Canada. For example, the share of immigrants admitted to Canada under the skill-based classification rose to 58% of 321,035 immigrants admitted in 2018 from 41% of 256,641 immigrants admitted into the country in 1993. Over the same period, the share of immigrants admitted under the kinship-based family class declined from around 44% to 26.5% indicating that the increase in skill-based admissions came at the expense of kinship-based admissions.

Skill-based admissions

There are substantial differences across receiving countries in their approaches to the selection of skill-based immigrants. Some receiving countries pursue a long-term growth strategy through skill-based immigration, while others use that category of admissions to meet short-term demand for labor in certain sectors of the economy.

There are two main approaches for skill-based admissions: supply-driven policies and demand-driven policies. Supply-driven policies are exemplified by the points systems in Canada and Australia whereas the employer-based admissions system in the US is the pioneering model for demand-driven policies.

Supply-driven policies

In 1967, Canada became the first country to introduce a point system to select skill-based immigrants. Australia followed in the early 1970s and New Zealand in 1991. In general, point systems assess applicants by assigning points for age, work experience, education, language ability, and occupation. Applicants may also receive points for arranged employment, close relatives in the destination country, spouse's education level, prior work experience, and education received in the destination country. These characteristics are believed to promote the economic integration of immigrants into the country. Admission is granted if the total points accumulated pass a threshold. In this system, having an arranged employment is not required to get admission and immigrants typically look for employment after their arrival. Rewarding points for occupation captures short-term labor demand conditions, and along with general human capital characteristics such as education and experience, aims to increase the employability of immigrants.

The Canadian point system was designed initially to meet short-term labor market needs by assigning points to specific occupations that were deemed to be in short supply. Starting in the early 1990s, a human capital approach was adopted instead, with a focus on general human capital characteristics and the long-term economic prospects of immigrants rather than on the country's short-term labor market needs. The Australian point system was based on the same ideas as the Canadian point system: points were awarded for human capital characteristics. In the presence of a large pool of applicants, the point system has been effective in generating high-skill immigrant flows in large numbers.

A serious challenge to the Canadian point system was the marked deterioration in the labor market performance of successive immigrant arrival cohorts despite substantially higher education levels. This was evidence of major difficulties in the transfer of foreign human capital. Updating detailed occupation lists in a dynamic labor market with rapidly changing demand conditions proved to be difficult. Characteristics that play an important role in achieving success in the labor market—such as practical knowledge in a job, motivation, creativity, ability to work in teams—could not be evaluated on paper applications. Given these challenges, both the Canadian and Australian point systems have been substantially revised over time as policymakers have searched for a more effective selection mechanism.

By the late 1990s, Australia was responding to the rising number of admissions by revising its admissions system. Formal assessment of vocational-level English and post-secondary qualifications was introduced and occupations were required to be on a skilled occupation list. These changes aimed to increase the employability of immigrants soon after their arrival and emphasized a short-term view. In an important change, Australia also introduced a mechanism for facilitating the transition of temporary workers and international students to permanent resident status through skill-based admission categories.

Following the Australian model, Canada has adopted several changes since the mid-2000s that have increased the emphasis on meeting the short-term needs of the economy, with a greater reliance on temporary workers and international students as a source of future skill-based admissions. During this period, Canada experienced a sharp increase in the number of temporary workers and international students (the pool of potential skill-based immigrant applications of the future). Immigrant admissions were decentralized by allowing provinces to nominate immigrants based on local labor market needs.

These changes in Australian and Canadian admission policies aimed to solve the language ability and credentials recognition problems that were impediments for effective use of immigrants’ skills. The changes adopted included elements that brought Australian and Canadian policies closer to demand-driven policies.

Demand-driven policies

Demand-driven policies are characterized by the requirement of a job offer for admission, which ensures immigrants have employment in the destination country by the time they arrive. The government determines the cap on total admissions and the eligible occupations, and regulates and oversees the labor certification process. Employers play an important role in selection by making job offers to prospective immigrants. Through the recruitment process, employers evaluate the credentials and experience of potential immigrants, their motivation, creativeness, and adaptability to the work environment. The resulting immigrant pool is the result of employer demand that reflects short-term labor market conditions.

The US is the leading example of a host country where a demand-driven policy is employed for employment-based admissions. Most employment-based immigrants in the US are former temporary workers sponsored by their employers. Many of these workers were international students in the US who were later employed on a temporary basis following graduation [2]. Thus, the screening mechanisms of US higher education institutions and employers play a pivotal role in shaping the applicant pool for permanent residence. This approach encourages foreign students graduating from US institutions of higher education to stay in the country and work, creating a pool of foreign talent for employment-based admissions. By the time these prospective immigrants apply for permanent admission, they will have demonstrated both their language ability and their employability by holding a high-skilled job.

Outside of the US, most of the high-skill immigrants in Europe, Japan, and Korea are admitted through systems that have elements of the demand-driven model. Demand-driven models are also used for admission of temporary immigrants into the US, Canada, and Australia [2].

Developments in high-skill immigration practices

Skill-selective policies have been on the rise globally as a growing number of developed and developing countries aim to attract the world's talent pool. According to United Nations data on international migration policies, the share of governments with a policy to raise the level of immigration of highly skilled workers increased from 22% in 2005 to 40% in 2019. In 2019, 5% of governments had policies to lower skill-selective inflows, 19% aimed at maintaining current levels, and 37% had no policies in place. While the attempt to raise the level of high-skill immigration was evident across all regions, it was especially pronounced in Asia, Europe, and Northern America. In addition to competing to attract global talent, several countries—such as India, China, Taiwan, Germany, Turkey, and New Zealand—have created incentives for their high-skill emigrants to return.

Following Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, other countries also adopted points-based selection systems, including the UK (2002), Czech Republic (2003), Denmark (2008), the Netherlands (2008), and Japan (2012). The European Commission proposed the Blue Card in 2007, an EU residence and work permit, with elements of a demand-driven policy which requires a valid work contract or a binding offer for a skilled job. With the introduction of the Blue Card, the EU is aiming to compete globally in attracting talent.

In order to improve economic outcomes of skill-based immigrants, host countries have recently adopted several changes in selection systems. These changes introduced elements of demand-driven policies into point systems by giving preferential treatment to applicants with host-country education credentials and work experience, facilitating the processes for international students graduating from host country education institutions to adjust their status to permanent residency. Foreign students are considered as a reserve for future high-skill immigrants by an increasing number of host countries, including Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

Countries also make use of a mix of policies for selection. For example, while in Canada immigrants under the Federal Skilled Worker Program are selected via a points system, the country accepts temporary immigrants based on an employer-driven system. While employing a demand-driven system for most employment-based immigrants, the US also admits immigrants under the EB1 visa where no offer of employment or labor certification is required provided that the applicant can demonstrate international recognition of their outstanding achievements in an academic field or demonstrate extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics.

Immigrant outcomes by visa category

Studies that can identify the class of admission provide direct evidence on differences in skill levels and economic outcomes by visa category.

Evidence on skill differentials for Australia and Canada shows that skill-based immigrants have higher levels of education and report higher language ability than other classes of immigrants [3], [4]. For example, among skill-based immigrants arriving in Canada between 2000 and 2001, male skilled workers had 3.9 more years of schooling and female skilled workers had 3.4 more years than their counterparts in the kinship-based immigration class [4]. The analysis for the US, relying on occupation data to infer skills, similarly finds higher skill levels among employment-based immigrants compared to kinship-based immigrants [5], [6].

Whether higher skill levels lead to better economic outcomes depends on multiple factors, including credentials recognition, access to networks, and post-migration human capital investments. Several studies investigate the differences in economic outcomes across visa categories and how these differences evolve over time.

Australian evidence on the labor force participation and employment outcomes of immigrants who arrived during the mid-1990s shows that, for the most part, immigrants selected based on skill requirements have better labor market outcomes shortly after arrival [3]. Skill-based immigrants are also found to outperform family class immigrants three years after arrival in terms of earnings, both unconditionally and also conditional on human capital characteristics [7].

Canadian evidence indicates no differences in labor force participation but lower employment rates for skill-based immigrants than for kinship-based immigrants shortly after arrival. In general, these gaps persist over the first 18 months in the country [4]. Studies that investigate longer-term outcomes report higher earnings among skill-based immigrants and these differences remain after controlling for human capital characteristics [4], [8], [9].

The US context also provides evidence of higher initial earnings among employment-based immigrants compared with kinship-based immigrants, but these fade over time [5]. Comparing occupations that immigrants hold in the source and host countries, employment-based immigrants in the US are found to be the group least likely to experience occupational downgrading [6]. More favorable labor market outcomes for employment-based immigrants are also reported in the European context such as in the UK and the Netherlands [10], [11].

This evidence of more favorable outcomes for skill-based immigrants, however, masks the serious problem of immigrant skills being underutilized. For example, Canadian evidence shows that financial returns to human capital characteristics are much lower for immigrants (most of whom amassed that human capital in a foreign country) than for native-born workers [4], [8]. Skill underutilization is a common problem in all host countries regardless of the selection system they adopt. Lower returns for skills mean either that assessed characteristics do not reflect the true productive capacities of immigrants or that other barriers such as credentials recognition or licensing problems, weak job networks, and discrimination prevent more productive use of the skills immigrants bring to the country. Countries that seek to maximize the contribution of immigrants to the economy need to pay as much attention to developing policies that facilitate the transfer of foreign human capital as they do to the rules of admission.

Trade-offs in immigrant selection

Skill-based immigration accounts for a majority of admissions in some countries, while kinship- or humanitarian-based admissions have the largest share in other countries. The resulting skill composition of immigrants relative to native-born workers has important implications for the wage structure.

Favoring high- or low-skilled immigration

Immigration of low-skilled workers reduces the earnings of low-skilled workers and enhances the productivity of high-skilled workers and capital in their host countries, resulting in an increase in wage inequality. Immigration of high-skilled workers, on the other hand, lowers the income of high-skilled workers and raises the incomes of low-skilled workers and the return to capital, leading to a reduction in wage inequality. Hence, while in countries where immigrants are relatively more skilled than natives a reduction in wage inequality may be observed, the opposite may be the case if immigrants are predominantly low-skilled [1].

High-skill immigrants may boost innovation and productivity and enhance long-term growth. However, since these immigrants also depress high-skilled wages, this may reduce incentives among natives for skill investments—which would depress economic growth. The net effect on growth depends on whether immigrants are more innovative and on the type and extent of externalities (both positive and negative) created by the influx of high-skilled immigrants. The evidence on the effect of immigration on innovation is mixed [12].

Targeting short- or long-term needs of the economy

Immigrant admissions in demand-driven systems generally reflect short-term demand conditions. Immigrants admitted for short-term needs may be readily employable and improve competitiveness of firms. However, these benefits may disappear over the long term as demand conditions change. There are concerns whether reported shortages are genuine and maintaining a list of occupations that are in high demand is challenging in rapidly changing economic contexts. Workers sponsored by employers due to short-term demand may be exploited and adjustment of domestic labor supply in shortage occupations will be slowed if temporary workers are hired at low wages. Employers who hire immigrants for short-term needs also do not face indirect costs, such as unemployment insurance claims in the event of an economic downturn, which creates a moral hazard problem.

Supply-driven policies with a long-term human capital perspective, in contrast, have the advantage of selecting immigrants based on general productivity characteristics rather than on changing short-term needs. The difficulty in transferring foreign human capital, especially when there is no explicit offer of a job awaiting the immigrant, is the major challenge in this approach.

Generating large flows of high-skill immigrants

Demand-driven systems that require job offers heavily rely on a large reserve of individuals with host country work and education experience. This requires that there is a large pool of potential immigrants with host country language capability, and that the host country's educational institutions and labor market opportunities are attractive on a global scale [13]. Due to these requirements, generating a large number of immigrants through a demand-driven system may not be feasible for some countries. Supply-driven systems, however, are better suited to generating large flows of high-skill immigrants.

Other implications

International students, who serve as a reserve for future skill-based immigrants, incur high tuition and living costs during their studies. In the presence of these costs, giving priority to foreign graduates in skill-based admissions implies that relatively well-off individuals from source countries are at the front of the queue in admissions. The rise of predominantly high-skill immigration policies globally and the rising share of skill-based immigrants in total admissions reduce the chances of migration for the low-skilled, who face the most severe economic pressures in source regions and who stand to gain the most from migration. Tighter rules of selection in supply-driven systems, particularly mandatory pre-migration language testing, also imply a shift in country of origin compositions of immigrants away from non-English-speaking source countries and may reduce the diversity of immigrant intakes.

Declining opportunities for legal immigration for the low-skilled may result in higher levels of undocumented migrant and refugee flows. Fiscal costs of economic integration programs for language and training programs may be reduced as immigrants become higher-skilled but only at the expense of higher costs incurred for managing larger refugee waves and border controls for deterring undocumented entries.

Another important aspect of a high-skilled immigration policy concerns the implications for sending countries. The highly selective policies of developed countries may drain sending countries of much-needed skills and human capital, thereby aggravating the economic challenges for developing countries.

Limitations and gaps

Available evidence on economic outcomes by visa category is mostly limited to the first few years after arrival. Evidence on longer-term differences is important for assessing whether short-term differences persist. The extent of differences in the lifetime contributions of skill-based and other immigrant streams is also unknown. Pursuing supply-driven or demand-driven policies may affect native skill acquisition, labor markets, and innovation differently. Future studies should address these differences which can have important policy implications.

More research is also needed to understand the declining fortunes of successive cohorts of immigrants across many receiving countries and the challenges in transferring foreign human capital. For more effective utilization of immigrant skills countries need to consider factors beyond immigrant selection. In particular, rigorous empirical assessments of the role of integration policies that target immigrants—such as language courses and active labor market programs—and the characteristics of labor market institutions may be especially fruitful.

Summary and policy advice

Developed countries vie to attract skilled workers. Generally, skill-based immigrants have better economic outcomes than other immigrants, at least in the short to medium term. However, the number of potential immigrants with high economic prospects is limited and immigrants are becoming increasingly selective about the labor market prospects and social rights a host country offers.

Receiving countries are increasingly relying on international students and temporary workers as a source of skill-based admissions because this system bypasses problems of credentials recognition and admits immigrants with a secured job. So far, however, this channel has contributed just a small fraction of all permanent immigrants. In countries where per capita immigration and skill-based admissions are large this system may not yield the desired number of immigrants.

Demand-driven systems have limited effects on the economic integration of the overall immigrant population, since a large number of immigrants continue to arrive through kinship ties and for humanitarian reasons.

There are important challenges and trade-offs associated with a skill-based admission system:

Economic integration—Admissions based on skills do not necessarily mean easy economic integration of immigrants. Many difficulties impede the transfer of foreign human capital to host countries, which leads to underutilization of immigrants’ skills. Immigrant selection systems and policies that facilitate economic integration should be considered as complementary.

Design—The design of skill-based immigration systems is complex and has many features that are context-specific, hence there are no blueprints. Skill-based selection policies should reflect the characteristics of the country's labor market and the applicant pool.

Short-term skill shortages—Some countries try to predict short-term skill “shortages” and admit immigrants with corresponding skills. Identifying shortages is difficult and, in a dynamic environment with a sluggish policy response, such policies may be ineffective or counterproductive.

While the economic impact, costs, and benefits of the alternative admission strategies inform decision making, which immigration policy that policymakers should pursue depends on the political consensus in the host society that involves both economic and non-economic factors.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the “Graphical abstract,” adds recently available evidence, discusses new policy developments, frames the discussion around demand- and supply-driven policies, and includes new “Key references” [2], [6], [7], [8], [10], [11], [12], [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Abdurrahman B. Aydemir