Elevator pitch

Expenditures on job placement and related services make up a substantial share of many countries’ gross domestic products. Contracting out to private providers is often proposed as a cost-efficient alternative to the state provision of placement services. However, the responsible state agency has to be able and willing to design and monitor sufficiently complete contracts to ensure that the private contractors deliver the desired service quality. None of the empirical evidence indicates that contracting-out is necessarily more effective or more cost-efficient than public employment services.

Key findings

Pros

From a theoretical point of view, contracting out job placement services opens this market up to competition, which might decrease costs compared to the public delivery of such services.

If contractual arrangements and performance measurement can be sufficiently well-designed, contracting-out could improve job placement, at least for certain population groups.

Contracting-out allows the state to expand or reduce service capacity and to hire specialists for particular target groups while avoiding the long-term commitments that are often found in the public sector.

Cons

For the responsible state agency, ensuring the quality of private employment services puts great demands on contract design and monitoring systems.

It is by no means guaranteed that sufficiently well-designed contracts and adequate monitoring can be designed (or that the responsible state agency is even pursuing this goal).

Empirical studies for several countries indicate that – under given contract structures – the public provision of placement services performed equally well or even better than the private provision of such services.

Author's main message

Contracting out job placement services might save costs and provide a service capacity buffer in times of increasing unemployment. However, state agencies must be able to ensure a suitable balance between services and quality, and to carefully monitor and evaluate private provider outcomes. Empirical evidence finds that public employment agencies are at least equally as successful in placing the unemployed as private providers. Conditions for successful implementation include the conclusion of complete contracts, adequate monitoring of quantity and quality, low entry barriers into the market, and longer-term development processes.

Motivation

In many welfare states, the provision of placement services for job seekers has been an important task for public employment services (PES). Since the end of the last millennium, the state provision of such services has come under increasing criticism for a presumed lack of effectiveness and cost-efficiency. These criticisms related at least partly to large public deficits in those years and the development of a theory of government failure. While effectiveness refers to the question which provision of services has the largest positive impact on individuals' labor market outcomes (as employment rates and wages), cost-effectiveness refers to the ability to organize activities in a way that minimizes costs for a given quantity and quality of services.

Contractual responses to these criticisms were the contracting-out of placement services (where competition mostly takes place ex-ante during a tendering process), the provision of placement vouchers (where providers directly compete to be chosen by clients), and the notion of New Public Management for the public sector (replacing input-based administrative structures with output-oriented performance management). The focus of this article is on the first response.

Discussion of pros and cons

Broad international adaptation

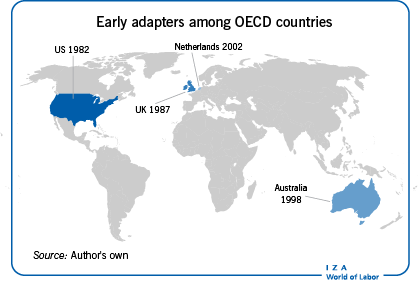

Contracting-out service delivery is the most frequently used mode of interaction between the public sector and private providers of placement services. Many states have enacted reforms involving the contracting out of at least part of the placement services to private providers [1]. In the US, for example, the privatization of welfare services has increased significantly since the 1980s, when individual states were given more autonomy to formulate policies. The most resolute approach has been adopted by Australia, where placement services for all unemployed persons have been tendered out to private providers since 1998. Other prominent examples are Great Britain and the Netherlands, which started to contract out portions of their placement services at the beginning of this century (see illustration on p. 1).

The contents of contracting out

Contracting-out takes place on so-called quasi-markets [2]. In the context of job placement services, a state agency specifies the tasks to be performed by private firms. Competition for entry into the market (but not within the market) is achieved by means of a tender. One or more providers win the right to supply a specific set of services, while a state agency maintains some control over the respective activities. Competition then suspends until the state initiates a new bidding process. Quasi-markets differ from markets as non-profit providers might be among the bidders, the state agency decides about purchasing and contract terms, and service recipients may not be able to choose between providers.

Contracting practices vary between countries in many respects, including [1]:

Scope: Contracting-out might encompass all unemployed persons (as in Australia), selected groups of unemployed persons (as in the Netherlands), or shares of all or selected groups of unemployed persons (as in Germany). Contracts can also be confined to particular regions. Services might be restricted to placement and counseling, or they may also include elements of training or other services.

Bidding process and design of contracts: Contracts may be short-term or cover very long periods. Countries often apply a combination of quality and price tender criteria. The actual remuneration design could encompass several components. Payment is often made up of a combination of an upfront fixed payment per job seeker and subsequent premiums for achieved results (e.g. successful placement).

Characteristics of private contractors: These could be for-profit firms or non-profit organizations (e.g. non-governmental organizations or charities). One or several private providers might cover a specific region, while main contractors might be selected to manage a network of smaller subcontractors (as in the British Work Programme from 2011 to 2018). Contractors may be large or “one-person-providers” serving only a small number of clients [1].

Potential advantages of contracting-out

First, proponents of contracting-out argue that it increases cost-efficiency by creating competitive incentives for job placement providers and might thus save money compared to the public provision of similar services [2]. Clearly, this requires contract structures setting stronger incentives for successful placement activities than a public organization can provide. This does not necessarily require that private providers be able to organize their work more efficiently, set better incentives, or be more innovative than their public counterparts – they might instead use less manpower to provide less intensive services, pay lower wages, or offer fewer benefits to employees than state agencies. A study for the Netherlands analyzed contracting-out decisions made by Dutch municipalities and found that they seem to be driven predominantly by cost considerations – in particular, municipalities with tight budgets have a larger share of private contracting.

Second, private providers might be able to deliver services of a higher quality than a public provider. They could provide more specialized services, react more flexibly to the requirements of the clients and the market, and be more innovative than traditional welfare bureaucracies. The quality must, however, be ensured through criteria applied in the tendering process.

Third, contracting-out makes it possible for states to rather quickly expand or reduce service capacity and to purchase specialists for particular target groups without engaging in the long-term commitments frequently found in the public sector [1]. Thus, private services can provide a helpful capacity buffer in times of increasing unemployment.

Fourth, contracting-out could increase consumer choice. If the unemployed are, however, assigned to one specific particular contractor, then they do not have more choice than they would with a public provider. If they have to choose between providers, not all job seekers are able to cope with a wide spectrum of opportunities (for instance, due to their lack of knowledge on the merits of different potential providers).

Fifth, contracting-out part of the placement services can help to maintain some competitive pressure on caseworkers in public services.

Sufficiently complete contracts as a key condition for contracting-out

Contracting-out services can only achieve the goal of enhancing efficiency if a quasi-market can be successfully established [2]. This applies not only to placement services, but also to other areas in which governments have long had monopolies. Government services can indeed be classified according to the possibility of concluding contracts for a relevant quality [3]:

Perfect contractibility: The quality can be contractually agreed upon and be enforced at negligible cost (e.g. garbage-collection).

Moral hazard: The contract is on an imperfect measure of quality, which thus suffers from moral hazard (e.g. placement services).

Unverifiable quality: The quality is known, but unverifiable; thus, no enforceable contract is possible (e.g. fire protection).

Credence goods: Only the service provider knows the quality (e.g. residential youth care).

With respect to placement services, the service providers are subject to moral hazard: Incomplete contracts give contractors scope for cutting costs and quality, and poor service quality might result if the tendering process places too much emphasis on low priced bids. Then service providers might deploy the following strategies:

“Creaming” or “cherry-picking”: A strong emphasis on performance-based payments may encourage private providers to focus on individuals with rather good labor market prospects and – if possible – to refuse services to unemployed job seekers with poor employment prospects. This problem can be avoided if providers are obliged to accept all individuals assigned to them.

“Parking”: A high proportion of upfront payments, which are not contingent upon successful job placement, may encourage service providers to neglect unemployed individuals who are difficult to place and to reduce service quality. This could be mitigated by regular contract monitoring and participant surveys, or by assigning homogeneous groups of unemployed persons to private providers.

“Gaming”: Service providers might try to exploit further weaknesses in program designs. If, for instance, performance-related bonuses were paid for placing job seekers in employment for a fixed period of time, then there would be an incentive to mainly find jobs for clients for exactly that period of time (instead of permanent positions) and to repeatedly reap the bonus for an individual assigned to the provider.

The state agency thus has to draw up sufficiently complete contracts to ensure that the desired level of access for all groups of unemployed persons is achieved and to make certain that the desired quality of services is delivered. Some authors argue that contractual incompleteness could be overcome by outsourcing to non-profit rather than to for-profit organizations. A further issue is that the state agency must spend sufficient effort in setting the right conditions to obtain qualitatively high services – e.g. it has an incentive to allow for poor quality if the service provision is evaluated and the state agency would prefer to (further) use its own staff for service provision.

What a good design looks like also depends on the respective circumstances and whether the quantity and quality of the desired services can be adequately measured. Of course, this requires that these services are carefully defined first; beneath placement into employment and time out of benefits they might e.g. also include participation in labor market programs, earned income in a new job, the duration of a new job, and client satisfaction. Monitoring systems must enable the responsible state agency to track participants and the desired outcomes. However, there is often a lack of information about the effectiveness of individual service providers. Gross integration rates (i.e. the rate of job placements) are therefore often used as a proxy for net impact (i.e. the additional share of job placements achieved by the provider, compared to a situation without an assignment to private services).

An example of a rather sophisticated approach is the Australian Star Rating [1]. The assessments are conducted by the Australian Department of Employment, Skills and Training and rate providers across Australia on their ability to place and retain job seekers in sustainable employment, adjusted for differences in job seeker characteristics and differences in local labor market conditions. This also introduces an element of ex-post competition as jobseekers can compare provider performance. While studies find that these star ratings do not have much influence on the decisions of the unemployed, however, they are used by the responsible state agency to allocate business shares to individual providers: Past performance carries a substantial weight as a selection criterion. Newer studies have criticized, however, that this system induces providers to focus on their star ratings as a means to renew their contracts and to neglect to improve the quality of services.

Further conditions for the successful implementation of a quasi-market

An additional condition for setting up a quasi-market is that barriers to market entry are low. If expected profits are small or vary considerably with the state of the labor market, and if market entry involves non-negligible costs, then the level of ex ante competitiveness will be low. Contracting-out involves transaction costs for the market participants. Private placement providers have to train caseworkers in specific skills, establish and foster relationships with potential employers, and perhaps acquire specialist software. Setting-up quasi-markets may also involve substantial (and quite complex) transaction costs on the part of the state agency; preparing and monitoring contracts that specify tasks and remuneration issues requires specific expertise.

Furthermore, the implementation of an efficient contracting system requires a longer-term development process [1]. Gains might emerge only over a longer period of time, after public officials have been able to exclude poor performers and to improve their own performance management. It could be useful to favor well-performing providers in subsequent rounds of tendering, for instance, by using reputation indicators. As this creates entry barriers for new entrants, thus reducing competition between providers, an option to terminate contracts if performance drops below a pre-defined threshold is necessary with this setup. However, it should also be noted that some unemployed persons require placement services over a long-time horizon, which decreases the contractibility of services and would be an argument in favor a public provision of placement services for this group.

Randomized controlled trials on contracting-out placement services

Theoretically, placement services delivered by private providers may be more or less effective and cost-efficient than services delivered by the PES. Thus, the relative benefits must be investigated empirically to determine the real-world consequences of job placement privatization. Randomized controlled trials that assign individuals to either public or private services avoid any problems of unobserved heterogeneity in both groups. The number of such trials conducted so far, however, is still rather small [1], and most of them have focused on particular groups of workers. In the experiments described below, public and private providers were not allowed to refuse unemployed persons assigned to them, so creaming (or cherry-picking) could not occur.

The largest study – with around 44,000 participants – was conducted in France in 2007 [4]. Job seekers were assigned to either a private or a public program offering intensive job search assistance, or to a control group receiving standard services from the PES. Compliance rates (the share of those who were assigned to a particular treatment and did in fact take advantage of it) amounted to approximately 50%in both intensive treatment groups. The results show that intensive job search assistance had a positive impact on exit rates to employment, and the effect was considerably higher for the public than for the private program. Furthermore, a basic cost-benefit analysis strongly favors the intensive public program. The authors show that the differences were not driven by a selection effect, but that private providers did probably spent less effort on clients with good employment prospects as they presumed that these would find a job anyway. Furthermore, three different types of private providers seemed to have mastered the counseling task differently.

Some field studies have analyzed the effects of contracting-out on the labor market prospects of hard-to-place unemployed persons. A randomized field experiment in two German labor market agencies from the years 2009-2010 assigned hard-to-place unemployed individuals to either intensive in-house placement services or to contracted-out job placement services [5]. Compliance was around 80%for assignments to privately provided services and 100%otherwise. Over a period of 18 months from assignment, and compared to contracted-out intensive services, assignment to the intensive public employment services reduced the accumulated number of days in unemployment by one to two months. However, two-thirds of this effect can be attributed to labor force withdrawals. One explanation would be that in-house (i.e. PES) teams have been more successful in encouraging individuals to deregister from unemployment. From a fiscal point of view, the public provision of services performed slightly better.

Two further studies refer to Swedish unemployed persons with particular labor market impediments. The first analyzes the effects of contracting-out for groups of hard-to-place unemployed persons during the period 2007-2008 in three regional labor markets; more specifically, the focus was on unemployed persons under the age of 25, immigrants, and people with disabilities [6]. Compliance rates were below 30%. Overall, the study did not find any differential effects on the probability of employment due to enrollment in private versus public placement services, and the same holds for the subgroup of disabled persons. However, evidence did show stronger positive short-term effects for migrants and negative effects for young unemployed individuals who participated in private services. No cost-benefit analysis was provided. The second Swedish study investigates the effects of vocational rehabilitation conducted by public or private providers on the labor market prospects of individuals who had been out of work long-term due to sickness during the period 2008-2009 [7]. Compliance rates were around 80%. No differences could be determined in the employment rates and the average costs of rehabilitation.

A study for Denmark [8] analyzes the effect of contracting out placement services for highly educated job seekers in two metropolitan areas who hold a university degree and have been unemployed for less than three months. Private providers delivered more intense, employment-oriented services, which were offered earlier on during unemployment. However, the effectiveness of public and private services did not differ regarding subsequent shares in regular and subsidized employment, in non-benefit receipt and in unemployment. Total costs without transfer payments were significantly higher in the private program. Note that this study also provides a systematic overview of the features of other available experimental studies.

Finally, an early study for the State of Michigan analyzed an experiment where hard-to-place participants in the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program were randomly assigned to private providers, where they received more intensive services. It reported no substantially higher effects on job-finding rates; the compliance rates of the individuals assigned were below 50%.

All in all, none of the experimental studies cited above indicate that contracting-out is necessarily more effective or more efficient – results are either indifferent or in favor of public services. The design of the experiments, however, mostly does not permit disentanglement of potential channels that may have had an impact on program effectiveness; an exception is the large-scale French study. Candidates for such channels are, for instance, the contents and focus of services, differing caseloads (number of unemployed individuals per caseworker), and the performance standards in the private and public settings.

Studies on different designs of contracting-out schemes

A study using detailed information on the contract design and payment of German private employment service providers in 2009 and 2010 indicates that, on average, high performance-based payments have positive effects on private provider performance in the short and longer run. In contrast, high upfront payments decrease the likelihood of reemployment for certain subgroups of clients and private providers [9].

A number of studies investigate design issues for the Netherlands. One study compared the impact of “no cure, less pay” and “no cure, no pay” contracts (i.e. payment methods that primarily or only reward agencies for successful job placement) and found that the latter were associated with some cream-skimming. However, it also found that the share of shorter-term job placements for workers with good placement prospects increased somewhat [10]. These effects could not be found for hard-to-place unemployed persons.

Another study investigates the effects of changes in scoring weights in tenders for contracted-out services (i.e. how important different criteria are in the tender selection process). Increasing the quality components resulted in higher priced bids, while increasing the weight of indicators for reputation and for intended integration plans improved placement rates [11].

Studies focusing on the ownership of the private provider

Several studies compare the performance of non-profit and for-profit job service providers. A study for the Netherlands study finds strong evidence that for-profit agencies are more selective, as well as by sending back clients with bad job prospects or by encouraging clients to start a program (to receive additional fixed pay components) [12]. With respect to job placement results, the study detects only small differences between for-profit and non-for-profit providers. A previous study for the US came to qualitatively similar conclusions. For Belgium, a study estimated the effectiveness of contracted-out services for the long-term unemployed that were delivered by for-profit and non-profit firms. The intervention reduced unemployment duration, but also increased employment instability and labor market withdrawals. Overall, for-profit firms performed best.

With respect to a different service (ambulances) in a Swedish city, authors found that private providers performed better for contracted measures (as response time), but worse on non-contracted outcomes (as mortality). The authors conclude that non-profit firms might be an intermediate solution if for-profit firms are subject to moral hazard and contracts are incomplete, but state production of a service is inefficient. Another author found for the Indiana vocational rehabilitation program, however, that performance-based contract for non-profit providers worked well for measured indicators, but had no impact on non-measured outcomes [13]. He points out that relational contracting that cultivates informal relationships between parties and trust may be an important complement to formal performance-based contracts, especially when aspects of quality are not contractible.

Limitations and gaps

The empirical evidence on the effectiveness and cost-efficiency of competing modes of delivery of job placement services is ambiguous. Moreover, findings from one region will not necessarily hold for others. For instance, the characteristics of the unemployed population and the labor market situation might vary between regions, programs might consist of heterogeneous components, or the contract design and monitoring system might differ. In addition, observed differences in the outcomes of private and public providers might only be partially attributable to the inherent aspects of each respective method. Examples include frictions in the transfer of unemployed individuals from public employment agencies to private providers, and the possibility that caseworkers in public services use sanctions against the unemployed as an incentive device [4]. More carefully tailored research is needed to fill these knowledge gaps. In particular, research should try to disentangle potential channels for differential performance results.

Summary and policy advice

Many countries have contracted out at least a portion of their job placement services to private providers, largely based on the idea that this will be more cost-efficient for the state. However, the few available randomized controlled trials that compare private and public placement service delivery methods indicate that job placement by the PES is neither less effective nor less cost-efficient than services provided by private placement agencies. In fact, part of them even indicate that public provision had been both more effective and more cost-efficient than the private alternatives existing in the investigated regions. Having said that, these findings cannot be generalized; each country has unique circumstances that must be taken into account when designing subcontracting protocols and for determining an optimal mix of public and private placement services. But designing contractual arrangements and reliable performance measurements (making providers aware that their quality of their services is monitored) remains a major challenge. Just organizing a tender and hoping for an improved cost-efficiency of service provision is by no means sufficient. Before introducing a large-scale contracting-out program, countries should assess the effectiveness and efficiency of the desired program by conducting a pilot study. Ideally, this would be done using a randomized controlled trial accompanied by a qualitative implementation study, which would allow policy makers to adjust the program as soon as problems with contract design or placement management become obvious.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Daniel S. Hamermesh, two anonymous referees, the IZA World of Labor editors, Pia Homrighausen and Sarah Bernhard for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work by the author (together with Gerhard Krug) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [4]. Version 2 of the article updates the state of the literature and adds new Further readings and Key references [12] and [13].

Competing interests

The author is employed at the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), which conducts independent research. It is funded by the German Federal Employment Agency and the German Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares that she has observed these principles.

© Gesine Stephan