Elevator pitch

Public attitudes toward immigration play an important role in influencing immigration policy and immigrants’ integration experience. This highlights the importance of a systematic examination of these public attitudes and their underlying drivers. Evidence increasingly suggests that while a majority of individuals favor restrictive immigration policies, particularly against ethnically different immigrants, there exists significant variation in these public views by country, education, age, and so on. In addition, sociopsychological factors play a significantly more important role than economic concerns in driving these public attitudes and differences.

Key findings

Pros

Recent surveys suggest that the majority of people support relatively restrictive immigration policies and would like to see a decrease in the number of immigrants.

Personal characteristics of survey respondents and immigrant groups significantly influence attitudes toward immigration and immigrants.

Sociopsychological factors, such as issues related to ethnic/cultural identity, play a substantially more important role than economic concerns in driving anti-immigration attitudes.

Cons

Designing surveys that allow for cross-country comparisons for countries with different immigration experiences and legal structures is challenging.

Researchers’ current understanding of the inter-play between micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors remains limited.

To identify and disentangle the various causal channels that shape public attitudes toward immigration more research is needed.

The role of macro-level institutional and sociopolitical forces in shaping public attitudes has been largely ignored.

Author's main message

The primacy of sociopsychological factors in shaping attitudes toward immigration highlights the limited effectiveness of economic policy interventions in reducing anti-immigration sentiments. A comprehensive and effective approach to address negative attitudes toward immigration therefore necessitates careful attention and engagement of sociopsychological concerns, prejudices, and stereotypes that underlie such opposition. Policymakers should avoid restricting public views toward immigration to considerations around individual behavior driven by material self-interest when evidence clearly suggests that they do not belong to that framework.

Motivation

Immigration has become one of the most controversial and important topics in public policy. It features highly on the political agenda of most major immigrant-receiving countries and figures prominently in political campaigns. For example, according to data from Eurobarometer—a longitudinal multi-topic pan-European survey of public opinions—the percentage of respondents who considered immigration as one of the two most important issues facing their country increased from 14% in 2005 to 22% in 2017, changing its importance ranking among more than a dozen issues from sixth to second.

Public attitudes toward immigration can play a significant role in shaping policy debates and immigration regulations, with the (proposed) construction of a southern-border wall in the US as one of the most prominent and recent examples. These public views are also important contributors to immigrants’ social and economic integration into the host country; as well as issues of social cohesion and racial/cultural identity. It is therefore important, both for descriptive political economy and for policy design, to understand and disentangle the different factors that influence individual preferences and public opinions toward immigration. This helps to better understand who supports more-/less-limiting immigration policies and why.

There is extensive research in economics regarding the performance of immigrants in their host country as well as their potential spillover effects in different domains. However, there has been substantially less systematic research on the extent to which the performance of immigrants as well as their (perceived) social and economic impacts shape public attitudes toward immigration. Moreover, little attention has been paid to the interplay between self-interested economic concerns and other potential drivers such as racial, cultural, social, and political factors.

Discussion of pros and cons

General views toward immigration: A brief summary

Public views toward immigration are not a historical constant, they change considerably over time and across countries. Various factors, including different survey designs as well as cross-country differences in previous immigration experiences, legal structures, current composition of immigrants, and existing immigration policies, make it difficult to identify the underlying sources of these differences. Nevertheless, general results from recent major surveys in developed countries paint a relatively similar picture: the majority of people across these countries are in favor of relatively tight immigration policies that limit further settlement of immigrants, particularly those that are ethnically different.

For example, results from the International Social Survey Program that covers 22 countries suggest that only 7% of respondents support a more open immigration policy [1]. Similarly, results from the European Social Survey suggest that only 15% of respondents welcome “many” immigrants of a same race/ethnicity into their country, while only 9% welcome those of a different race/ethnicity [2]. According to the data from Eurobarometer 2018, only 40% of respondents express positive feelings toward immigration of people from outside the EU. Moreover, according to seven years of data from the British Social Attitudes Survey, 66% of white respondents oppose further settlement of immigrants from India and 70% oppose settlement from Asia [3]. For Immigrants from Europe and Australia/New Zealand, however, these numbers are 46% and 33%, respectively.

Immigrants’ qualifications and personal characteristics, such as their education level, language proficiency, country of origin, and religion, are found to be important for respondents and to significantly influence their expressed views toward immigrants and immigration [2], [3], [4]. In general, respondents with more or less liberal views toward immigration attach a similar degree of importance to characteristics such as education and language proficiency. However, there seem to be differences in the degree of importance attached to other characteristics, such as immigrants’ religion or whiteness. For example, results from the European Social Survey suggest that respondents who support a tighter immigration policy put almost twice as much weight on these two attributes compared to those who support a more liberal immigration policy [2].

Respondents’ individual characteristics are also found to play an important role in shaping their attitudes toward immigration. Results from different studies highlight educational attainment as one of the key factors affecting an individual's attitude toward immigration, with the less-educated often holding less liberal views [2], [3], [4], [5]. The respondent's age is also found to be important, with older respondents holding stronger views against immigration [2]. Religion is yet another influential factor. More specifically, compared to people from other religions or of no religion, Christians of all denominations are found to more strongly oppose immigration [2]. Political orientation is also strongly associated with a person's views toward immigration [6].

Apart from the characteristics of immigrants and respondents, public views toward immigration are strongly linked to two broad sets of issues. The first is grounded in what is sometimes referred to as political economy, which attempts to explain views toward immigration with reference to the economic self-interest of the native-born population. Empirically, these issues are examined within the framework of competition between immigrants and natives over resources, whether in the labor market or through the welfare system. The second set of issues is what some scholars refer to as sociopsychological factors [4]. These factors are grounded in group-related attitudes and symbols that are linked to race, religion, customs, and traditions, as well as other ascriptive features.

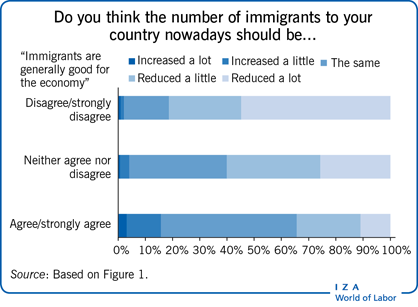

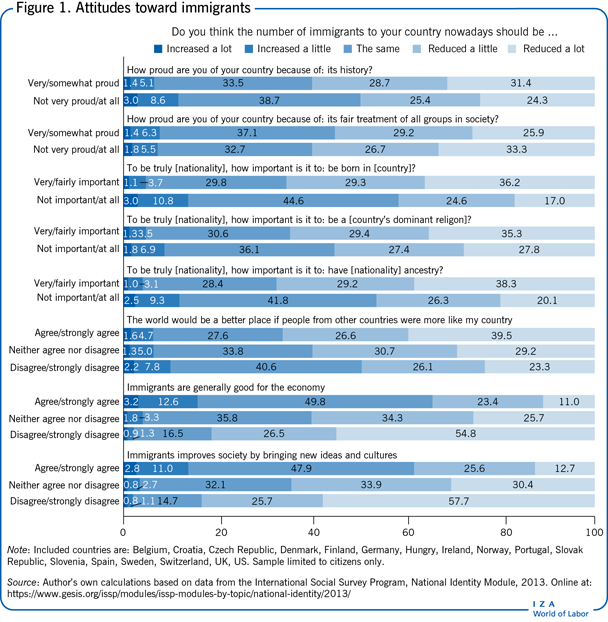

Results from the International Social Survey Program reported in Figure 1, as well as other public surveys [2], [4], acknowledge the role of these issues in shaping attitudes toward immigration. More specifically, public views in favor of a tighter immigration policy are often strongly correlated with:

more negative views on almost all economic consequences of immigration, such as its impact on wages, jobs, and the welfare system;

more negative views about the effect of immigration on crime, cultural life, and overall social tension;

higher desirability of homogeneity in customs and traditions, common religion, and to some extent a common language and a single school system;

stronger sense of national pride and patriotism; and

lower desirability of social contact with immigrants.

This strong correlation raises an important question: what is the relative importance of these different factors in forming attitudes toward immigration? An attempt to answer this question inevitably raises other critical questions, including: (i) how do these different factors interact with each other and to what extent are some the causes or the consequences of the others? (ii) to what extent are these identified issues manifestations of deeper underlying factors?

The potential interplay between these different factors suggests that analyzing some of them in isolation from others could seriously hinder or even distort the understanding of the underlying factors that shape attitudes toward immigration. As such, identifying and disentangling the casual factors underlying attitudes towards immigration is a critical step in addressing the real concerns, misperceptions, and prejudices related to immigration. It also allows a better understanding of the link between individual characteristics (of both immigrants as well as natives) and differences in views toward immigration.

Economic determinants of attitudes toward immigration

Despite a large body of literature, most of the economic research dealing with immigration is both technical and narrow, often focusing on very specific issues. Moreover, there is considerable disagreement among economists regarding some baseline assumptions (e.g. how to measure migration flows, or what type of production function to use) within this relatively limited scope of research. As such, when reviewing the existing evidence it is important to identify the relevant assumptions and research questions in each study to determine how the answers provided fit into the overall narrative.

Given the importance of labor income to people's economic welfare, the effect of immigration on wages is considered to play a critical role in shaping preferences regarding immigration. Different economic models, however, produce different predictions regarding the effect of immigration on wages [3], [7]. The economic effects of immigration are primarily driven by the impact immigration has on the size and the composition of the labor force in the host country. More specifically, immigration increases the total supply of labor relative to other inputs. Moreover, if the distribution of skills among immigrants is different from the native population, immigration will also change the skill composition of the labor force. This could potentially create both losers and winners in the host country. For example, if immigrants on average have lower skills than natives, then a simple model of economic self-interest, such as the factor-proportions analysis model, would suggest that low-skilled native workers will be against the inflow of low-skilled immigrants [7]. On the other hand, high-skilled workers and employers, who benefit from depressed wages of low-skilled workers, will be in favor of low-skilled immigration.

Despite the intuitive appeal of such a simple framework, more comprehensive economic models, such as the Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson trade model, suggest that with sufficient flexibility in the economy's mix of outputs it is reasonable to expect a small or non-existent negative impact on wages [3], [7]. Examining the literature in fact confirms that there is very thin empirical evidence of large distributive effects of immigration, including adverse effects on wages [2], [4], [8].

The fiscal effect of immigration (i.e. the effect of immigrants on taxes and transfers) is another channel through which economic self-interest may affect attitudes toward immigration [3], [9]. For example, the Trump administration recently announced a new policy that makes it more difficult for applicants legally in the US to obtain a green card if they have accessed or are deemed likely to access certain social services. Findings from several studies suggest that concerns about the fiscal effects of immigration are equally important to, or even more so than, concerns about potential labor market impacts in shaping anti-immigration sentiments [10]. In line with this thinking, incorporating a basic model of public finance into the standard factor-proportions model suggests that immigrants’ potential impact on taxes and transfers is likely to affect natives’ post-tax income and therefore their attitudes toward immigration [9]. For example, if low-skilled immigrants have a net negative fiscal effect (i.e. on average they receive more in benefits than what they pay in taxes), then a larger number of low-skilled immigrants will increase fiscal pressure by raising taxes or reducing per capita benefits. High-skilled immigrants, on the other hand, will have the opposite effects. Consequently, higher-income natives are expected to more strongly oppose low-skilled immigrants and more strongly support high-skilled immigrants relative to their lower-income native counterparts, despite the perhaps more intuitive expectation by which direct competition for jobs would induce the opposite reaction.

However, there exists substantial disagreement among researchers about the fiscal effects of immigration [6]. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of these effects requires careful assessment of the complexities involved in the relationship between immigration and public finances [10]. Studies that try to address these complexities often find positive fiscal impacts (see [10] for examples). Nevertheless, drawing accurate conclusions regarding the long-term fiscal effects of immigration has proven difficult. This is partly because such conclusions require an accurate assessment of the present value of immigrants’ lifetime fiscal contributions, which in turn requires estimating unknown future parameters such as future earnings pathways, future return decisions, and the future direction of taxes and welfare systems [10]. In summary, while reviewing the related literature does not seem to provide conclusive evidence regarding strong positive or negative fiscal effects associated with immigration, there exists evidence from several studies that immigration can have net fiscally positive effects in particular cases [10].

Sociopsychological determinants of attitudes toward immigration

The discussion in the previous section raises an important question: if systematic evidence suggests that immigration does not have negative long-term impacts on the economic life of the native-born, why do people hold strong views against immigration? The answer could lie in the role of non-economic factors. In other words, perceived threats to economic self-interest, which on the surface seem to inform attitudes toward immigration, may be grounded at a deeper (conscious or subconscious) level in preferences for homogeneity and perceived threats to a wider sense of social and ethnic identity [2]. However, for several reasons, such as stigmas attached to the racially charged language of social and racial identity and homogeneity, such concerns may be expressed (or disguised) by individuals in more economic terms.

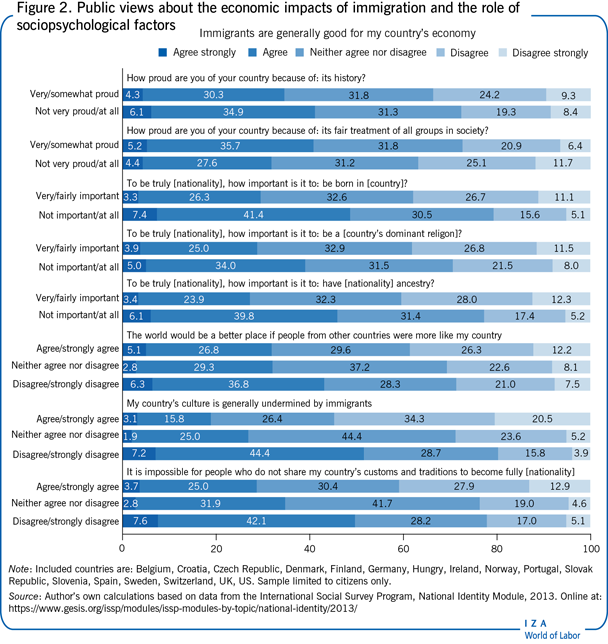

The patterns illustrated in Figure 2 lend more validity to this hypothesis. More specifically, Figure 2 clearly suggests that respondents’ expressed opinions regarding the economic benefits of immigration are closely tied to their views on other immigration- and non-immigration-related social, cultural, and racial issues. In other words, these results demonstrate that public views regarding issues that are generally considered irrelevant to one's unprejudiced assessment of the economic benefits of immigrants nonetheless appear to be closely linked to it. Therefore, perceived threats of immigration seem to be (partly) fueled by cultural, religious, and ethnic differences to the immigrant population and the threats that these differences are perceived to pose to a sense of social and racial identity and superiority [3].

Models developed by sociologists and psychologists help illuminate some underlying mechanisms that are critical in understanding attitudes toward immigration. While some models emphasize individual-level mechanisms, others focus on group-level causes where hostility toward immigrants is driven by perceived threats against the group's resources or status, rather than the individual themselves.

Individual-level theories highlight the role of individual mechanisms in generating prejudice against other groups. The previously reviewed models of economic self-interest fall into this category. Other theories include sociopsychological approaches that explore mechanisms grounded in individual emotional and/or cognitive processes that (partly) operate at a subconscious level. They attribute the underlying source of prejudice to “psychological displacement of fear or anxiety onto others” that are developed during childhood, or to “expression of stereotypical beliefs resulting from cognitive limitations and distortions in attribution,” p. 587 [11]. While there are numerous sociopsychological experiments that confirm the existence of such individual-level processes, these individual-level factors seem to fall short in explaining extensive variation in prejudice across time and space [11]. It is well-understood that prejudice is most prevailing when it is institutionalized by a dominant group. This highlights the importance of group-level explanations in gaining a comprehensive understanding about prejudice and attitudes toward immigration.

Group-threat theory is one of the earliest group-level theories of prejudice that highlights the collective nature of perceived threats that emerge via inter-group competition within a wider social/cultural landscape [11]. In this process, dominant groups develop outgroup prejudice driven by feelings of superiority and privilege, as well as by a fear of losing these prerogatives. In other words, in this model “prejudice is a defensive reaction against explicit or (usually) implicit challenges to the dominant group's exclusive claim to privileges” [11], p. 588. A modified version of this theory, which is known as the “realistic group conflict theory,” posits that it is the inter-group competition over real resources and accepted social and cultural practices that translates into a belief in group threats and results in outgroup prejudice and hostile attitudes [2], [11]. The main distinction between the two theories is that while the former considers outgroup prejudice a response to perceptions of group interest that may not be grounded in any real group interest, the latter grounds it in threats against ingroup actual interests [11].

Whether anti-immigration sentiments are driven by real threats against actual interests, or whether they are driven by what is known as “symbolic threats” depends on various factors, including people's perception of ingroup versus outgroup, and the extent to which the diversity of interests across groups is perceived to translate into zero-sum versus mutually beneficial interactions. Theories of symbolic threats, which are sometimes counterposed against self-interest or realistic group conflict explanations, suggest that natives’ response to cultural or ethnic differences to immigrants are driven by prejudiced attitudinal predispositions toward immigrants that are not rooted in real tangible threats or objective vulnerabilities. For example, both Europeans and Americans are found to overestimate the number of immigrants in their country, and anti-immigration sentiments are found to be larger among people with larger misperceptions about the number of immigrants coming to their country (see [4] for examples).

Factors such as political ideology and mass media are also considered as moderating forces that contribute to ingroup versus outgroup conceptions and generate/intensify fears of symbolic threats that lead to hostility toward particular groups of immigrants [4], [6]. Evidence from various studies suggests that political ideology, which is conceptualized as “a personality predisposition which precedes expressed attitudes about specific political topics” [6], p. 1179, is linked to cognitive orientations that affect tolerance for diversity and preference for change as well as social/cultural homogeneity. There is also empirical evidence that links ideological orientation and party identification to anti-immigration attitudes (see [6] for examples).

Political ideology, while relatively stable over time, could mediate changes in attitudes toward immigration at different points in time by conditioning how individuals respond to contextual changes arising from significant events involving immigrants, media attention, or actions of politicians and opinion leaders. In addition, politicization of immigration, which often occurs in times of hardship and tension, could perhaps explain why anti-immigration sentiments often appear to be driven by concerns that are not firmly grounded in systematic evidence. In other words, during some historical periods, including the present, immigration gets injected into the public discourse by being anchored to more dominant issues such as economic anxiety or racial and social tensions. Therefore, while the connection between these dominant issues and immigration remains unclear to the public, immigration will be evaluated in terms of those dominant issues that invoke social or economic anxiety. This is consistent with findings from several studies which show that while changes over time in the rate of immigration do not affect attitudes toward immigration, year to year changes in other macro-level conditions, often unrelated to immigration, such as the unemployment rate or GDP growth, do influence attitudes toward immigration [12], [13].

Economic versus non-economic factors: Empirical evidence

While some studies provide empirical evidence that supports the role of self-interested economic concerns in determining attitudes toward immigration, this association has been shown to be fragile and potentially grounded in other non-economic factors [3], [4]. For example, the documented weaker opposition of more-educated natives toward immigration has been interpreted by some studies as being mediated through their weaker exposure to the potential adverse effects of immigration on wages.

However, other studies highlight that this association might actually be driven by differences in cultural values and beliefs about the sociopsychological effects of immigration rather than by self-interested economic concerns [3], [4]. There are a variety of other factors that can explain the association between education level and pro-immigration attitudes. For example, more-educated respondents are found to be less ethnocentric, to attach higher values to cultural diversity, and to exhibit more optimism toward the economic impacts of immigration [4], [5]. This is consistent with evidence indicating that more highly educated natives are more supportive of all types of immigrants, irrespective of immigrants’ skill levels and respondents’ labor force status (see [4] for examples).

Therefore, one needs to be very careful in interpreting the empirical association between labor market characteristics like education and skill level and attitudes toward immigration as an indicator of the primacy of labor market competition as a driving factor [3], [4]. This is especially important since there is evidence that suggests the association between labor market characteristics and attitudes toward immigration is very sensitive to inclusion of other non-economic attitudinal regressors such as political orientation [3].

In fact, reviewing the more recent empirical evidence from studies that examine the role of both economic and sociopsychological factors in shaping attitudes toward immigration clearly suggests that sociopsychological factors, such as prejudice related to concerns regarding issues of cultural and ethnic/racial identity and homogeneity, play a substantially more important role than economic concerns in shaping attitudes toward immigration [3], [4], [5]. In addition, these sociopsychological issues are found to be particularly more important than economic factors in (i) driving anti-immigration attitudes amongst the less-educated and the lower-skilled, and (ii) opposition toward immigration from poorer and ethnically different countries [3].

Limitations and gaps

While recent studies have paid more attention to the relative contribution of different economic and sociopsychological factors in shaping attitudes toward immigration, more research is required to fill the current gaps and limitations in this area. Specifically, more careful work is needed to identify and disentangle the underlying causal channels and mediating factors that influence attitudes toward immigration. In doing so, future research could benefit from: (i) strengthening the causal identification of sociopsychological and economic concerns to enhance researchers’ understanding about how, when, and why they affect attitudes; (ii) developing a better understanding of the inter-temporal changes in attitudes and how they interact with economic, social, and political processes; (iii) more careful and systematic analysis of the interplay between various sociopsychological and economic factors, how they interact at different micro-, meso-, and macro-levels, and the extent to which some are the causes or the consequences/manifestations of others; (iv) paying more attention to the role of social and political institutions; and (v) more in-depth characterization and examination of systematic differences in attitudes across major immigrant-receiving countries such as Canada, the US, Australia, New Zealand, and across Europe. Doing so of course requires the availability of longitudinal and cross-country survey data that contains detailed and informative attitudinal questions.

Summary and policy advice

One common finding from most recent surveys is the prevalence of anti-immigration sentiments and the support for restrictive immigration policies, especially for immigrants from ethnically different countries. Examining the potential underlying sources of public attitudes toward immigration highlights the role of group-level sociopsychological concerns as well as labor market and social welfare concerns as three main contributing factors. However, a growing body of empirical evidence suggests that sociopsychological factors, such as prejudice related to concerns regarding issues of cultural and ethnic/racial identity and homogeneity, play a substantially more important role than economic concerns in shaping attitudes toward immigration [3], [4], [5]. This is also consistent with the existing empirical evidence that suggests it is difficult to find adverse economic impacts of immigration on the native population [2], [3], [8].

The primacy of sociopsychological factors in determining attitudes toward immigration highlights the limited effectiveness of economic policy interventions in reducing anti-immigration sentiments. It also suggests that addressing anti-immigration attitudes requires serious engagement of the sociopsychological concerns, prejudices, and stereotypes that strengthen ingroup versus outgroup perceptions, fuel cultural and racial antagonism, and intensify perceived threats to group identity associated with immigration. As scholars have pointed out, “we fail as scholars and as citizens if we seek to force these difficult [immigration] issues into the box of the politics of material interest, when they manifestly do not belong there” (see Gaston and Nelson, 2000, p. 112, in the Additional references).

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Mohsen Javdani