Elevator pitch

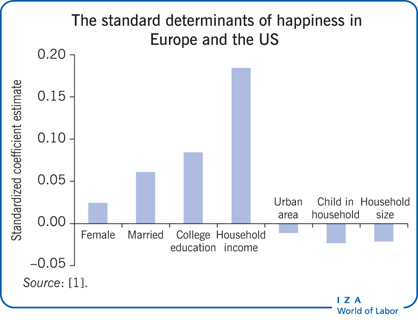

Flexible work time and retirement options are a potential solution for the challenges of unemployment, aging populations, and unsustainable pensions systems around the world. Voluntary part-time workers in Europe and the US are happier, experience less stress and anger, and are more satisfied with their jobs than other employees. Late-life workers, meanwhile, have higher levels of well-being than retirees. The feasibility of a policy that is based on more flexible work arrangements will vary across economies and sectors, but the ongoing debate about these multi-tiered challenges should at least consider such arrangements.

Key findings

Pros

Voluntary part-time workers have more life satisfaction and less stress and are more satisfied with their jobs than full-time workers.

Flexible approaches to retirement and to part-time work are linked to higher levels of well-being, at least in labor markets where flexible work is a choice.

Workers who remain in the labor force after retirement age are more satisfied with their health and are happier than their retired counterparts.

Flexible work times and retirement schemes can enhance well-being—which is linked to better health and higher productivity—and also reduce unemployment and pension burdens.

Cons

Changing employment and retirement schemes will have administrative, bargaining, and implementation costs for employers and employees.

Employers may incur short-term costs from shifting to shared and part-time work.

Such work arrangements are likely to be less feasible in countries with large informal sectors, where reducing precarious employment remains a priority.

Different cultural norms and labor market practices will affect the feasibility of such arrangements and will mediate their effects on well-being.

Author's main message

Unemployment and fiscally unsustainable public pension schemes will be critical issues facing both advanced and emerging market economies for the foreseeable future. Given the increase in labor-saving technology and aging populations, creative solutions are necessary. Flexible retirement and work time could be part of the solution and would enhance well-being. While the potential transaction costs of such arrangements, as well as their feasibility in more precarious labor markets, are concerns, policies that support more flexible labor market arrangements, including incentives for job-sharing and remaining in the labor force after retirement age, can help overcome these problems.

Motivation

Flexible work arrangements and retirement options based on more individual choice are a potential solution to some of the challenges of unemployment, aging populations, and unsustainable pensions systems around the world. These challenges, which relate in part to demographics and in part to the expanding role of labor-saving technology, trouble both advanced industrial and emerging market economies and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. And while the aging population will increase as a proportion of the total population in most countries in the next 30 years, the labor force is predicted to decrease. Creative solutions to this imbalance are needed.

New findings about well-being contribute some perspective. In addition to the well-known negative effects of unemployment on well-being, there are documented positive effects related to late-life work and to voluntary part-time work [1]. There may also be positive externalities for health and for labor productivity, among other benefits, as the research on well-being also finds strong and reinforcing links between well-being and better health and higher productivity.

At a time when unemployment, workforce productivity, and health problems related to an aging population present multifaceted challenges, exploring the potential contribution of flexible work arrangements in meeting these challenges is a low-risk and potentially high pay-off proposition. Experimenting with more flexible labor market arrangements in some target sectors—including additional incentives for job-sharing and for remaining in the labor market after retirement age—could be a first step. Such experiments would also yield additional evidence about the potential costs as well as benefits.

Much less is known, however, about the transaction costs related to shifting to more flexible arrangements and the differential feasibility of such arrangements across labor market sectors and cultures, as well as who should bear those costs. Given that such a shift could have multiple benefits for public health, public finances, and productivity, both the public and the private sectors should have some interest in making the necessary investments.

Discussion of pros and cons

Creative solutions to multi-tiered labor market challenges

The challenges of unemployment, aging populations, and unsustainable pension burdens were heightened by the 2008–2009 global financial crisis and the uneven recovery, with new entrants to the labor force taking the hardest hit. Youth unemployment rates peaked at 53% in Spain and nearly 40% in Portugal in 2012, compared with 16% in the US [2]. At the other end of the age distribution, given rising life expectancy and low and falling fertility rates, unsustainable fiscal deficits are forcing the reconsideration of public pension and retirement schemes.

How well different employment and retirement schemes meet people’s needs depends on their career objectives, innate levels of well-being, and stage in the lifecycle. Understanding how employment, retirement, and late-life work relate to well-being can contribute new insights into ongoing public discussions of how to resolve these multi-tiered labor market and fiscal challenges.

Given aging populations and the increasing role of work in retirement in several countries, understanding the well-being effects of both flexible work arrangements and late-life work may increase in relevance. Most Western economies have experienced a significant aging of the workforce. In Europe alone, the number of people aged 60 and older is expected to increase by some two million people a year over the next 30 years. At the same time, due to structural economic trends and technological innovation among other influences, the labor force is likely to shrink by more than one million workers a year [2]. Not surprisingly, there are discussions about raising the retirement age in countries including France, Germany, Japan, the UK, and the US.

An emerging body of work is exploring the relationship between well-being and productivity. Some work finds that higher levels of life satisfaction are associated with higher earnings and better health, while other research finds that having meaningful work is more important to productivity than is simple job satisfaction. Greater autonomy (including in relation to one’s working hours) also seems to play a role [3]. In contrast, the negative effects of work-related stress on health and longevity are well-documented [4]. Late-life work may provide social contacts and interactions, personal growth, autonomy, and a sense of purpose, which may be particularly important for older cohorts as opportunities for active social engagement dwindle.

One possible solution is that older workers could gradually reduce their working hours while remaining in the labor force (and continuing to pay taxes) well past official retirement age, with associated fiscal benefits from postponed public pension payments [5]. Late-life workers can be valuable to enterprises due to their experience and competence. In the US older workers receive a pay premium relative to their younger counterparts, suggesting that they are more productive [6]. Older workers may also play a role in training younger workers and apprentices, and some of the fiscal contributions from postponed retirement could be used to finance apprenticeships and training programs [1]. And as there is a shortage of skilled labor in some occupations, well-trained part-time older workers could fill multiple roles.

Much less is known about the transaction costs related to such proposals and about their effects on worker well-being. Much of what is known comes from small-scale experiments or from individual country programs. Germany introduced a number of flexible work arrangements during the recent Great Recession, and there is some evidence that these policies protected the labor market and even added jobs at a time that unemployment was soaring in neighboring countries.

Labor market arrangements and well-being

One innovative way to assess the costs of different labor market arrangements is through the novel metric of well-being, which typically covers large-scale population samples. Well-being is a broad concept that includes income and non-income dimensions. It has been assessed based on reported (subjective) levels of well-being, which is now a well-established measurement practice for assessing individual well-being. Initial work in this area finds that people who are unemployed have much lower levels of well-being than people with jobs in virtually every context. The psychological “scarring” effects of long-term unemployment are well-documented [7], [8]. Social norms related to employment also mediate these relationships, however, with the negative effects of unemployment sometimes mitigated by a relatively high local unemployment rate or by generous norms of unemployment compensation [9], [10].

Retirees’ well-being, meanwhile, varies across countries because of different retirement practices and the generosity of public pensions. And involuntary retirement reduces well-being in some contexts. While retirees in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries are happier than the average individual, retirees are less happy than average in Latin American countries and Russia, likely because their financial situation is more precarious [10], [11].

Other work arrangements also have differential effects on well-being, depending on the context. Several studies for OECD countries find that self-employed people are more satisfied with their jobs than those working for an employer [11]. In contrast, the evidence from Latin America, while mixed, suggests that people who are self-employed are less satisfied with their lives and jobs, due to the unstable nature of self-employment in the region. Self-employment is far more likely to be involuntary and in the informal sector there than in OECD countries [10].

Several studies of well-being and flexible work arrangements in advanced economies suggest that flexibility in work patterns, which gives workers more choice or control, is likely to have positive effects on health and well-being [12], [13]. An important channel seems to be work−family balance, and these studies suggest (unsurprisingly) that the positive benefits are greater for women than for men. As in the case of self-employment, though, the same arrangements may play out quite differently in labor markets with large informal sectors and more precarious employment.

Assessing the effects of labor market arrangements and late-life work on well-being

Novel data in the Gallup World Poll allows for further exploration of these relationships across several dimensions of well-being [1]. Evaluative metrics allow for assessing satisfaction with life as a whole, including over the lifecycle, while hedonic metrics capture well-being—including positive and negative affect, such as smiling and stress—as people live their daily lives. The Gallup World Poll provides individual-level data on well-being, income, health, and employment status, among other variables, for 160 countries around the world, beginning in 2005. Questions about employment were included beginning in 2009.

Research using the Gallup World Poll data focused on countries with roughly similar per capita income levels, labor markets, and demographic structures (France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, the UK, and the US) and explored the relationship between employment status, work arrangements, and subjective well-being (including job satisfaction) [1]. The study also considered whether there are additional well-being effects of late-life work.

About 30% of respondents in the sample were employed full-time, 6% were self-employed, 4% were unemployed, and 44% were out of the workforce. Roughly 8% reported that they worked less than 30 hours a week but did not want to work more than that, while 4% worked part-time but wanted to be employed full-time. As expected, voluntary part-time employment varies by gender. Specifically, 10.9% of men and 5.3% of women were voluntarily employed part-time.

In addition to the general trends, the employment statistics vary by country [1]. Germany and the UK had the highest proportion of voluntarily employed part-time workers (11%), while Greece and Portugal had the lowest (3%). Spain and the US had the largest proportion of respondents who said that they were employed part-time but wanted to work full-time (7%) among all countries in the sample. Sweden had the highest proportion of full-time workers (51%) among countries in the sample, while Greece, Italy, and Turkey had the lowest (25% each). Finally, respondents in Spain were the most likely to report that they were unemployed (12%), while those in Germany were the least likely (3%). These differences suggest divergent labor market conditions and norms about the acceptability of part-time work, which are also reflected in the results from regression analysis.

The out-of-the-workforce category includes students, people with disabilities, homemakers, and retirees. In 2009 and 2010, respondents who were not employed were asked whether they were retired. For the sample as a whole, about 60% of those who were not employed were retired. The percentage of those who were not employed who were retired was as high as 81% in Sweden and as low as 19% in Turkey.

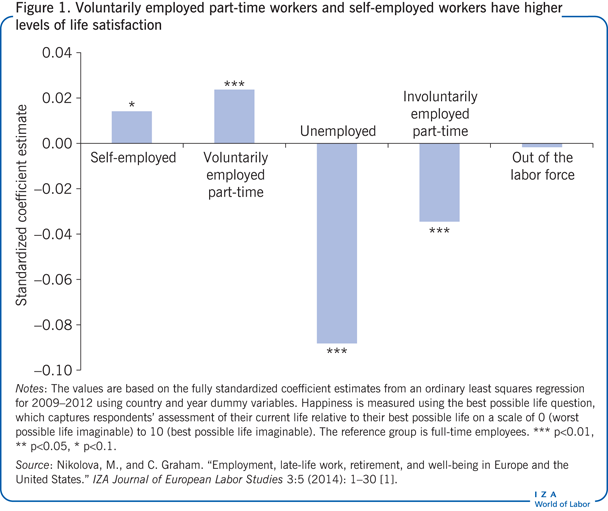

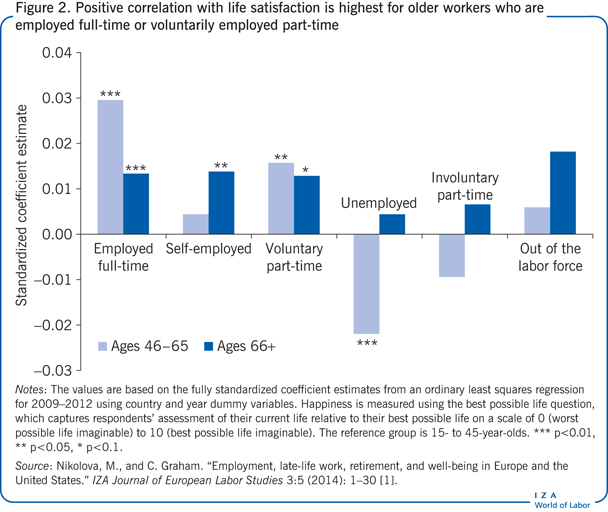

As noted above, unemployed people are, on average, much less satisfied with their lives than are their employed counterparts. In addition, though, voluntarily employed part-time workers and self-employed workers both have higher levels of life satisfaction than do those who are working full-time for an employer (Figure 1). The positive correlation with life satisfaction is highest for older workers (ages 46 and over) who are either employed full-time or voluntarily employed part-time (Figure 2). Voluntarily employed part-time workers also experience less stress than do their full-time employed counterparts, which is not surprising. Voluntarily employed part-time and self-employed workers were also more satisfied with their jobs, while self-employed workers were more likely than workers in other categories to report that their job was ideal.

An important caveat is that there are significant differences across countries in the extent of voluntary part-time work and thus likely in the extent to which social and labor market norms are accepting of part-time work. One can imagine that when this practice is rare, part-time workers could experience stigma or be relegated to inferior jobs. In addition, if flexible work arrangements prevent marginal workers from entering unemployment, then the appropriate comparison category should be unemployed workers rather than full-time employed workers. In this instance, then, the comparative well-being effects would be even greater. But that is again also likely to vary across countries, depending on norms. In Germany, which has encouraged flexible work arrangements, part-time workers might otherwise be in the ranks of the unemployed (and this may partially explain Germany’s lower than average unemployment rates compared with its counterparts in the EU). In contrast, these same kinds of workers are likely to be in the ranks of the unemployed in countries such as France and Spain.

While we still need to know more about these relationships, as well as the causal channels driving them (for example, it could be that more productive workers are more likely to report having meaningful work), there is sufficient evidence of a positive link between well-being, personal health, and labor market performance to suggest that the benefits of higher levels of worker well-being extend beyond the individual to society.

Late-life work

There is some country-specific research suggesting that late-life work has positive effects on well-being [11]. There are two problems in identifying the effects, though, stemming from endogeneity. One is self-selection, or the fact that retirees differ from late-life workers along a set of unobservable characteristics that are also correlated with their well-being. For example, those remaining in the labor force might be more motivated, more risk-loving, skilled, and so on, than those choosing to retire. These unobservable characteristics are also correlated with life satisfaction and could bias the results.

The second issue is the direction of causality. It is quite plausible that the people who chose to remain in the labor force after retirement were more satisfied with their jobs (and their lives) before retirement, and thus the difference between their level of life satisfaction and that of their retired counterparts later in life has nothing to do with remaining in the labor force. In addition, more educated workers are more likely to remain in the labor force than are less educated ones, not least as their jobs are usually less physically taxing [6].

Taking advantage of a very large and detailed data set, propensity score matching techniques were used to compare retired individuals with observably similar late-life workers [1]. Individuals were matched with others of the same age group, gender, marital status, education, religiosity, country, and year. Income matching was not done because the current income of retirees is by definition less than that of people who remain in the labor force. While the matching exercise is far from perfect, the results are both statistically robust and intuitive.

Workers who remained in the labor force past the retirement age (either in full-time work or in voluntary part-time arrangements) had higher levels of life satisfaction and hedonic well-being (smiling yesterday and happy yesterday) than did their retired counterparts, on average [1]. It is interesting to note that the life satisfaction of the late-life workers who worked full-time was higher than that of late-life workers who worked part-time. Late-life workers in general were also more satisfied with their health. Again, there are causality issues at play that suggest caution, as healthier people are more likely to remain in the labor force.

Regardless, the findings suggest that there are significant well-being benefits for late-life work for respondents who choose it.

An additional note is that the direction of the findings is very similar in two different specifications: the matching exercise just described and an ordinary least squares regression that included older workers and different work arrangements. Indeed, in the first round ordinary least squares regressions, the benefits of voluntary full-time and part-time work (including self-employment) were greatest for the oldest cohort (66 and older) in the sample. This constitutes additional confirmation that the results are not driven totally by unobservable differences across older workers.

Limitations and gaps

These findings stem from new research, and as such there are many unresolved questions. Clearly one is endogeneity, as it may well be that happier, healthier, and more motivated people are more likely to stay in the labor force, and thus the well-being benefits from working late in life may not be as large as the findings suggest per se. Unfortunately, the data did not permit matching according to health status (which is also related to income as well as to unobservable differences across individuals), and healthier workers are more likely to both stay in the labor force and to be happier.

Much of the research in this area suggests that choice matters. Retiring sooner than one would like has negative costs in well-being, but so does remaining in the labor force and working longer hours than one would like, particularly for workers who are in jobs that entail considerable physical or mental stress. The benefits of late-life work are linked to a person’s ability to choose to remain in the labor force and under conditions considered to be acceptable. These choices and abilities will vary a great deal, depending on the nature of labor markets in particular countries.

Another limitation is the lack of knowledge of the transaction costs and administrative burdens associated with making labor markets more flexible. Among other things, this would require creative job-sharing arrangements, which are more plausible in some sectors than in others. And while there are reasons to believe that combining the knowledge of older workers with the energy of younger ones could have productivity benefits, it is also plausible that ownership could be lower and shirking could be higher in conditions of shared responsibility. In addition, in contexts where part-time work or job-sharing arrangements depart from social and labor market norms, it is likely that workers who opt for such arrangements would face discrimination or be relegated to inferior jobs. Increasing our understanding of skill matching and how its feasibility varies across sectors will be an important input into these discussions going forward.

Summary and policy advice

Flexible arrangements and retirement options are a potential solution for the challenges of unemployment, aging populations, and unsustainable pension systems around the world. At least in Europe and the US, voluntary part-time workers are happier, experience less stress and anger, and are more satisfied with their jobs than other employees. Late-life workers, meanwhile, under voluntary part- or full-time arrangements, have higher levels of well-being (in some dimensions) than retirees. Higher levels of well-being are in turn associated with better health and greater productivity, suggesting that the benefits of such arrangements could extend beyond the individual to society. While the feasibility of a solution based on more flexible work arrangements will vary across labor markets and sectors, it has relevance for ongoing debates about the fiscal burdens of public pension systems at a time that creative solutions to these dual problems of aging populations and fiscal strains are a necessity.

Research suggests that maintaining workers’ health and supporting their employability into old age is important not only for governments but also for firms. Indeed, efforts toward these ends should be considered investments in future productivity, not least because once retirement-age workers leave the workforce, the probability that they will re-enter it is low, and their experience and human capital are essentially lost.

At the same time, we need to learn more about the transaction costs associated with making such changes and about how they may vary across employment sectors and institutional structures in particular countries. It seems that part of the story about exceptionally low unemployment in Germany, for example, has to do with the introduction of flexible work arrangements. Given everything that is known about the high transaction costs in terms of both well-being and productivity related to high levels of unemployment, these costs should clearly affect any calculation of the transaction costs of new arrangements.

That said, social norms about retirement and part-time work or job-sharing are also likely to mediate benefits to well-being and influence the feasibility of implementing such changes. These arrangements are less likely to be feasible in contexts where informal sectors are large and stable jobs are scarce.

It may be too early to recommend general labor market policies based on these findings, but given the very clear gains in well-being and the links between well-being and health and labor market performance, among other benefits, exploring ways to increase flexibility and introduce more choice in work arrangements and retirement decisions would be prudent. Experimenting with more flexible labor market arrangements in some target sectors—including additional incentives for job-sharing and for remaining in the labor market after retirement age—could be a first step, and one that could yield additional evidence about the potential costs as well as the benefits. Given the looming challenges of unemployment and the fiscal challenges posed by population aging and unsustainable public pension burdens in countries around the world, together with the potential positive contribution such changes might make, public support for experiments in this arena could have large pay-offs.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Milena Nikolova for extensive joint research and authorship on this and other topics related to well-being, as well as helpful comments on this article. The usual disclaimers apply.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Carol Graham