Elevator pitch

The recent rise of populism in advanced economies reveals major voter discontent. To effectively respond to voters’ grievances, researchers and policymakers need to understand their drivers. Recent empirical research shows that these drivers include both long-term trends (job polarization due to automation and globalization) and the rise in unemployment due to the recent global financial crisis. These factors have undermined public trust in the political establishment and have contributed to increased governmental representation for anti-establishment parties.

Key findings

Pros

Technological change and globalization create labor market effects that feed populist discourse.

Voting for populist parties is strongly related to the increase in unemployment due to the global financial crisis.

Rising regional unemployment is likely to increase populist appeal not only among those who have lost jobs but also among those who see diminished future opportunities.

Cons

The recent rise of populism may also be driven by other factors such as cultural backlash, identity, and the spread of social media.

There is only limited evidence on recent populists’ performance once in power.

So far, there is no evidence that populists deliver on their electoral promises to restore fairness and bring back inclusive economic growth.

Author's main message

The recent rise of populism has many potential causes, both cultural and economic. Growing evidence suggests that labor market disruptions due to globalization and technological progress as well as the crisis-driven spikes in unemployment have played a major role in the rise of populism in advanced economies. However, there is no evidence showing that populist policy agendas have a realistic shot at addressing such problems. Instead, standard progressive proposals such as stronger counter-cyclical fiscal policies to stabilize employment during recessions, fighting tax avoidance, strengthening social safety nets, and active labor market policies should be enacted.

Motivation

The recent rise of populism in advanced economies—particularly after the 2016 Brexit referendum and the 2016 US presidential election—has become a major challenge for liberal democracies. The populist tide has been explained by both economic and non-economic factors, including: cultural backlash against globalization, liberalism, and immigration; increased unemployment due to the recent financial crisis; and vulnerability of jobs to automation, outsourcing, and import competition. This article argues that the economic factors—the loss of jobs due to globalization and automation and the unemployment spike during the recent crisis—have played a major role. The inability of mainstream political parties to deliver shared prosperity has undermined public trust and provided ample opportunities for populist discourse. The rise of populism may therefore be justified by some as a corrective measure against the recent failures of traditional parties’ socio-economic policies. However, there is no evidence that populists have been able to improve economic performance once in power.

Discussion of pros and cons

Definition and measurement of populism

The analysis of the relationship between labor market performance and rising populism requires a rigorous approach to quantifying the latter. In within-country research, populism is measured as a vote share of the respective populist candidate at the level of subnational units (e.g. the relationship between local labor market performance and US counties’ vote for Donald Trump). Cross-country research mostly focuses on Europe where a cross-national comparable measure can be employed; namely, the vote shares of populist parties at the national or subnational levels. Different electoral rules across countries necessitate that researchers control for country fixed effects. This is why most cross-national research on populism is limited to advanced economies. While some emerging markets also observe populist tides, the lack of disaggregated data reduces opportunities for carrying out rigorous analysis.

To measure populism, it first needs to be defined. In economics, the conventional definition of populism dates back to a 1991 study in which the authors describe it as an “approach to economics that emphasizes growth and income redistribution and deemphasizes the risks of inflation and deficit finance, external constraints and the reaction of economic agents to aggressive non-market policies” [2], p. 9.

The authors were writing about the left-wing Latin American populism of the 1970s and 1980s. While this type of populism still exists today, the recent rise of populism comes primarily from the right side of the political spectrum; moreover, the typical modern populist agenda is not focused on economic redistribution. It is thus useful to use another definition, first introduced in 2017 and by now conventional in political science, the one of an anti-elitist and anti-pluralist “thin-centered ideology.” According to this definition, populism considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups: the “pure people” and the “corrupt elite” [3]. The people's “purity” by definition justifies the “popular will” as the only moral source of political power. The homogeneity of the people implies anti-pluralism—and no need for checks and balances.

Some political scientists argue that the definition of populism should also include an “authoritarian angle.” On the one hand, it is a natural concept, as the leader of the “pure people” can rule directly without checks and balances; many populist parties are indeed leaning toward a “strong leader” model. On the other hand, there are many anti-elitist and anti-pluralist parties that accept democratic norms, so most classifications of populist parties and politicians do not include an “authoritarian angle.”

The third definition was introduced in a study from 2018. The authors of this study argue that modern populist parties are the ones that satisfy three criteria: (i) they are against elites; (ii) they offer immediate protection against shocks; and (iii) they hide the long-term social costs of these protection measures [4].

How are these definitions related? For political scientists, the common thread is the anti-elite sentiment. For economists, it is the issue of unrealistic promises. Modern non-Latin-American populists mostly do not suggest irresponsible macro policies but their promises are still not sustainable. It has been argued that populism does not have to result in irresponsible macroeconomic policies; furthermore, populist pressure can be useful as a check on unaccountable technocrats and elite interest groups [5]. However, even without unsustainable fiscal and monetary policies, populists can undermine economic growth by removing political checks and balances. Investors value predictability around the so-called “rules of the game.” Removal of constraints on the executive can thus reduce incentives for long-term investment and undermine populist leaders’ chances to deliver on their promises of economic prosperity.

Economic drivers of populism

Globalization, technology, and support for populists

In recent decades, virtually all advanced economies have witnessed major labor market disruptions related to globalization and technological progress. While these are two distinct phenomena, they are usually discussed together for an important reason: globalization and technological progress reinforce each other. New technologies reduce transportation and communication costs, thus accelerating globalization. Conversely, lower barriers to cross-border trade and investments promote technological progress; access to a larger market strengthens incentives to innovate and to adopt new technologies.

Technological progress results in job polarization, creating jobs at the top and bottom of the skill distribution but destroying middle-skilled jobs in both manufacturing and services. High-skilled individuals see greater opportunities in knowledge-intensive service sectors that sell to global markets; their skills are complementary to the new technology. The benefits of global growth also trickle down to low-skilled manual jobs which are too lowly paid to be outsourced or automated. However, middle-skilled blue-collar jobs and routine white-collar jobs are increasingly automated or outsourced. When these jobs disappear, affected individuals have a tough choice of (i) reskilling and moving up to the high-skill segment of the labor market, (ii) moving down to the lower-paid manual jobs segment, or (iii) leaving the labor force. The second and third outcomes are obviously not appealing but the first one is not easy either—even if there are social safety nets and retraining opportunities, the cost of transition may be substantial. It is thus unsurprising that affected workers—especially the ones who are not able to find a new job—are justifiably disillusioned by the system.

While automation results in job polarization, competition with imports from countries with lower wages negatively affects employment in whole firms and sectors throughout the skill distribution. This effect has an important regional dimension: import shocks are concentrated in small communities that depend on one firm or one sector that is crowded out by import competition. The job losses in these firms or sectors can have devastating impacts on such communities.

The impacts of technological change and of globalization therefore create a fertile ground for populists. Both processes appear to benefit the “elites” (corporate leaders, bankers, lawyers, consultants, and so on); the mainstream parties supposedly do not do enough to protect the “hardworking and innocent people”—who certainly cannot be blamed for losing their jobs. The debate surrounding technological change and globalization therefore perfectly fits the populist discourse.

The solutions that populists promise may include redistribution (especially left-wing populists) or protectionism (in particular, “economic nationalism” as advocated by right-wing populists [6]) or both. Are these solutions realistic? Can they be implemented without slowing down income growth? These are important questions to consider when examining the experiences of populists in power.

Evidence on the implications of technological change and globalization

Recent studies provide evidence on the relationship between competition with imports and technology-driven job polarization, on the one hand, and the populist vote, on the other hand. In the US, the most convincing evidence comes from “China shock” studies that analyze variation in the exposure of local labor markets (at the commuting zone level) to the dramatic rise of Chinese imports in the 21st century following China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001.

In a series of studies, it has been shown that increased exposure to Chinese imports has a substantial negative impact on jobs and even marriage outcomes of less-educated American men. A study from 2017 analyzes five US election cycles from 2000 to 2016 and finds that rising Chinese imports caused a substantial increase in political polarization in congressional elections and a shift to the right in presidential elections [7]. The authors find that every one percentage point increase in imports from China since 2000 caused an additional 1.7 percentage point vote for Donald Trump in 2016.

A similar analysis has been carried out on the impact of automation on the Trump vote [8]. The authors proxy vulnerability to automation in a commuting zone by the share of routine jobs. They show that a one standard deviation (5 percentage points) increase in the share of routine jobs is associated with an increase in the vote share for Trump by 3–10 percentage points (depending on specifications, controls, and methodology).

Similar results have been found for Europe [6]. The authors of this study use data for import shocks at the NUTS-2 level (European subnational regions with populations from 0.8 to 3 million) and self-reported individual data on voting from the European Social Survey (ESS) in 15 Western European countries for 1988–2007. In order to identify causal effects, they instrument Chinese import penetration in European industries by Chinese imports in the same industries in the US. They find that a one standard deviation rise in Chinese imports implies an increase in self-reported support for extreme right parties by around 1.7 percentage points. This is certainly not a small effect given the average vote share of these parties across the studied countries is 5%. The authors also study the impact of automation on populist voting in Europe and find significant effects: a one standard deviation increase in exposure to robotization leads to a 1.8 percentage point increase in support for radical right parties.

Impact of the recent financial crisis

Unlike in the US—where the Great Recession was short-lived—in some European countries the crisis lasted for several years. The increase in European unemployment was substantial—from 7% in 2007 to 11% in 2013, and has been very uneven both between and within countries. This sharp and sustained increase in unemployment has undermined public trust in the “elites” who supposedly failed both to prevent the crisis and to protect the “people” from its effects. This experience once again perfectly fits the populist narrative. The main difference in this case is that the populists’ protectionism agenda shifts from anti-globalization to anti-EU. Populists argue that taking back control from the EU to the national capitals (where corrupt elites should also be replaced) can help prevent new crises and loosen fiscal purse strings to better support households suffering from the crisis.

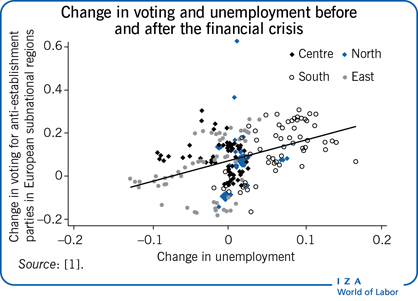

A recent study analyzes the voting outcomes in general elections in European countries at the level of subnational regions (220 NUTS-2 regions in 26 countries in 2000–2017) [1]. The authors use two approaches (difference-in-differences and panel regression) to show that voting for populist parties is strongly correlated with the change in unemployment rate after the crisis (versus before the crisis) (Illustration). The magnitudes are substantial: each percentage point increase in unemployment rate implies a 1 percentage point increase in populist vote share. In order to address the issue of potential time-varying factors that drive both unemployment and populism, an instrumental variable approach that considers the pre-crisis structure of a regional economy as a proxy for its vulnerability to the crisis is taken. For instance, regions specializing in real estate and construction before the crisis are deemed likely to be hit harder and thus experience a larger increase in unemployment. Using the pre-crisis economic structure as an exogenous predictor of change in unemployment allows for the identification of the causal effects of an increase in unemployment on the rise of populism. This effect turns out to be even larger than with the previous approaches: each percentage point increase in unemployment rate causes at least a 2 percentage point increase in populist vote share.

The aforementioned 2018 study examines the same issue but instead uses individual data on self-reported voting behavior from the ESS [4]. The authors explicitly model not just voting but also the turnout decisions as a function of individual-level economic insecurity (unemployment, self-reported income difficulties, and exposure to globalization proxied by being a blue-collar worker in manufacturing). They obtain much smaller magnitudes than in [1]: the causal effect of unemployment on the populist vote is only 0.08 percentage points for each percentage point increase in unemployment. Even when all components of economic insecurity are summed up, a one standard deviation change in economic insecurity increases the populist vote share by an order of magnitude less than in [1].

How can the differences in magnitudes between the two studies be explained? One potential explanation is that the first study looks at self-reported data from ESS, and respondents may not want to acknowledge that they voted for populists [4]. However, recent experiments suggest that this is unlikely [9]. The other possibility is related to the fact that the first examines the impact of individual unemployment [4], while the second looks at regional unemployment [1]. An increase in regional unemployment is likely to increase populist appeal not only among those who have actually lost a job but also among those who still have a job but see a lower chance of finding a new job and a lower probability of negotiating a pay rise.

These and other studies also look at attitudes toward political institutions and provide evidence for the mechanism linking the impact of the crisis and the populist vote: the crisis-induced shock supports the populist tide via undermining trust in national and European political institutions. On the other hand, the crisis had no impact on trust in other institutions such as the United Nations, police, or church, and almost no impact on generalized social trust (trust in other individuals) [1]. European citizens clearly attribute blame for the crisis to national and European politicians.

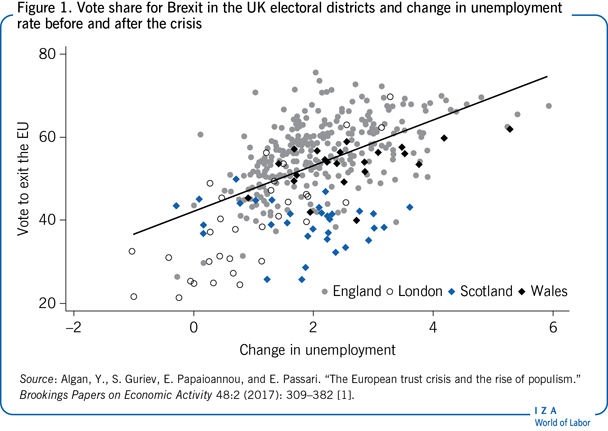

Finally, the impact of the crisis on populist voting has also been identified in several one-country studies [10], most importantly in the analysis of the 2016 Brexit vote. Two studies analyze the electoral district level (there are 380 districts in the UK) and show that increases in local unemployment significantly increased the Leave vote [1], [11] (Figure 1).

Populists in power

It appears clear that the rise of populism is driven by its supporters’ legitimate economic concerns. An important follow up question thus becomes: do populists offer better policy solutions?

Most of the existing evidence on populists in power comes from Latin America and the results have not been good. Many of the old populist regimes’ policies led to macroeconomic disasters which in turn resulted in decline or stagnation of real incomes. Recent Latin American populists—while being better aware of the costs of monetizing fiscal deficits (with an important exception of the Chavez-Maduro regime in Venezuela)—have still not been able to bring about macroeconomic discipline and sustainable growth.

What about the modern Western populists? So far there is only limited evidence on their performance since they have come to power in very few countries and only recently. Not all of them have managed to stay in office for a meaningful period. In order to evaluate the macroeconomic performance of those populists who stay in power for at least several years, economists use the “synthetic control” method. A 2019 study constructs a “doppelganger” for the US economy by computing a weighted average of GDP for 24 OECD countries where the weights are selected to approximate the quarterly evolution of the US economy in the 20 years before Trump's election [12]. The authors then compare the actual US economic performance and the doppelganger counterfactual after the election. They find that Trump has had zero net effect on US economic performance, neither in terms of GDP growth nor in terms of unemployment. This is not surprising, as the potential positive short-term impact of Trump's stimulus has been countervailed by the Federal Reserve's independent monetary policy and Trump's own trade wars.

In a different study, the same authors apply the synthetic control method to the UK economy. They show that in the first 2.5 years since the Brexit referendum, the UK has lost 1.7% to 2.5% of GDP relative to the counterfactual. Furthermore, they find that this decline is not due to uncertainty around the forthcoming Brexit, but rather because consumption and investment was suppressed from 2016–2018 because consumers and investors were certain of the looming economic slowdown after Brexit actually happens. These results are striking: while the UK government had not yet delivered Brexit itself, negative effects had already materialized because economic agents understood the impending impact of populists in power.

In Greece, the left-wing SYRIZA party moved away from its 2015 electoral promise of expanding redistribution and instead carried out a painful EU-imposed reform program, restoring competitiveness and resuming growth, and paying for this with an electoral defeat in 2019. Throughout its term, the SYRIZA government contemplated exiting the Euro Area, but understood that it would be even more painful and eventually unpopular. In this sense, the Greek experience is an example of populists who once in power realized and respected the economic constraints they faced—and behaved as a responsible government (rather than like old-style Latin American populists).

The longest spell of modern populists in power has been observed in Hungary where the FIDESZ party came to office in 2010 and won two subsequent elections in 2014 and 2018. Contrary to its promises, FIDESZ has neither delivered faster economic growth nor managed to turn around negative demographic trends. In 2010–2018, Hungary's per capita GDP growth (in constant purchasing power parity adjusted dollars) was 2.8% per year. Given that Hungary has continued to receive about 3% GDP every year in EU grants, this growth rate is not particularly impressive. For comparison, the unweighted average growth rate and median growth rate of other Central European and Baltic countries (Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia) was 3.3% and 3.4% per year respectively. Moreover, the Hungarian population continued to decline (also at a faster rate than the mean and median rates in Central European and Baltic states) so that in 2018 the government decided to fight labor shortages with a “slave law,” drastically extending the permitted number of overtime hours that employers could demand from employees. This reform has resulted in major street protests. Furthermore, unlike other Central European and Baltic countries, where both mean and median levels of corruption declined from 2010–2017 (according to the World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators), Hungary's corruption level increased substantially. In 2010, Hungary was a median Central European/Baltic country in terms of corruption. By 2017, however, it was behind these regions’ mean and median levels by 0.5 global standard deviations, and was close to the global average level of corruption (which is unusual for a high-income country).

Poland's Law and Justice (PiS) government has, on the contrary, done well in economic terms since its victory in the 2015 election. PiS is usually classified as a radical right party because of its “economic nationalism” and anti-minorities platform. However, one of its 2015 campaign promises was a major redistribution program—providing a lump-sum subsidy to families with children. PiS has fully delivered on this promise, which has contributed to reducing inequality and poverty. This redistribution program cost about 1% of GDP per year but has resulted neither in fiscal imbalances nor in slowing down GDP growth. Such strong economic performance may be explained by solid fundamentals owing to reforms implemented by the previous government and by the influx of about two million skilled, low-wage, and ethnically similar Ukrainian workers (who were welcomed to Poland despite PiS’ general anti-immigration stance). Finally, the government has also stepped up enforcement of value-added tax collection. In this sense, as PiS did deliver on its promises it was not surprising that it won the 2019 election with an even larger margin. At the same time, PiS has tried to undermine judiciary independence, politicize the governance of state-owned enterprises, and limit media freedom. These decisions are likely to have negative long-term implications not just for the state of Polish politics but for its investment attractiveness and therefore economic growth as well; as such, the jury is still out on this regime's ultimate legacy.

To sum up, the majority of populist governments do not outperform the mainstream parties they criticize, though some recent populists have not significantly underperformed either. Does this mean then that the rise of populism is harmless? As argued in a 2018 study, the answer depends on whether populists in power manage to undermine political checks and balances [5]. While there are many populist governments who respect the democratic process, there are also those with authoritarian leanings who have removed democratic checks and balances (especially when they cannot deliver on their socio-economic promises). This is likely to result in reduced accountability and increased corruption, crony capitalism, and subsequent economic underperformance.

Alternative explanations

While the studies above point to automation, competition from imports, and crisis-driven unemployment shocks as important drivers of the recent rise of populism, there are also alternative explanations, including growth of immigration, the cultural backlash against liberalism, and the spread of social media [10]. The evidence for the first two factors, however, is not straightforward. For example, in the case of immigration, the studies cited above argue that concerns about immigration are endogenous to the decline of employment opportunities—and therefore are economic in nature. Moreover, unemployment has been shown to increase ESS respondents’ concerns about the economic effects of immigration and not the cultural ones [1]. In the UK, it is unemployment rather than immigration that had a significant impact on the Brexit vote [11]. It has even been shown that a negative relationship exists between the level of immigration and the Brexit vote at the NUTS-3 level [6].

In theory, even if the aggregate economic impact of immigration is positive, it still creates winners and losers—very much like trade and automation. Therefore, the secular increase in immigration as well as the recent refugee crisis may have contributed to the rise of populism. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development's 2018 Transition Report “Work in Transition” provides a survey of ten studies on the impact of exposure to immigration on populist voting in Europe. The findings from these studies vary substantially not only in the magnitudes of the effects but also in their signs, depending on the intensity, composition, and nature of immigration flows. For example, if the influx of immigrants is large (as in the case of Syrian refugees landing on Greek islands), then it is likely to result in a higher populist vote. However, a small increase in immigration (e.g. about one immigrant or refugee per 100 natives) actually decreases the populist vote, which is consistent with contact theory (which posits that under certain conditions contact with a minority group can reduce the prejudice toward the group).

Evidence on the cultural backlash and the importance of identity is mostly limited to correlational evidence; these factors change very slowly over time, so it is very hard to come up with a convincing strategy for identifying the causal relationship. It is also difficult to argue why identity and cultural factors—that are highly persistent—have given rise to such a surge in populism now. The most obvious explanation is that it is the economic hardship that activates the cultural backlash. This implies that cultural backlash is essentially a mechanism through which job polarization or crisis contributes to the populist vote. Overall, it is the interaction of economic and cultural factors that remains the most exciting avenue for future research on the drivers of modern populism.

As shown in a study from 2020, there is substantial evidence on the contribution of the spread of social media to the recent rise of populism [10]. It is not clear however which mechanisms drive this relationship. It is plausible that the simplistic populist message is better suited for online communication technologies. If this is the case, then job polarization and unemployment spikes still play a key role: the spread of online media only reinforces the populist narrative based on economic grievances rather than conjures it out of thin air.

Limitations and gaps

While recent research has provided ample evidence on the role of job polarization and crisis in the rise of populism, there still remain many questions related to magnitudes, non-linearities, and interactions. First, recent studies identify very different quantitative estimates of the impact of labor market disruption on populism. Further research is required to understand how these magnitudes depend on the initial conditions as well as the social, economic, and political context. Second, most studies analyze linear relationships while there are likely to be economies of scale and critical mass effects (e.g. due to electoral thresholds and cross-regional spillovers). Third, the effects of globalization, automation, and crisis-driven spikes in unemployment likely interact with each other and with other drivers of populisms (such as cultural factors and the new communication technologies). These questions will hopefully be addressed by future research.

Summary and policy advice

The recent rise of populism is to a substantial extent explained by labor market disruptions caused by globalization, technological progress, and the spike in unemployment during the recent financial crisis. There is, however, no evidence that populists manage to solve these problems once in power. To improve employment opportunities for workers displaced by globalization and technological change, governments should provide generous safety nets and active labor market policies and upgrade life-long learning systems. As technology- and trade-related shocks are often geographically concentrated, there is also a strong rationale for regional and place-based policies. To stabilize employment during recessions, countries need to implement stronger counter-cyclical fiscal policies.

To pay for the active labor market policies, regional policies, and counter-cyclical buffers, structural reforms should be enacted that enhance competitiveness, productivity, and economic growth. Additional revenue could also be gained by eliminating opportunities for tax evasion and tax avoidance by the rich. This is a difficult task that requires international cooperation. Despite the challenges involved, it is crucial—not just for fiscal reasons but also for restoring public trust in political elites. The populist narrative is much stronger if elites are not paying their fair share of taxes. In order to stand up to populists, the centrist parties should renew themselves and regain public trust through carrying out meaningful reforms and delivering inclusive growth.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author (co-authored with Yann Algan, Elias Papaioannou, and Evgenia Passari) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Sergei Guriev