Elevator pitch

Trade regulation can create jobs in the sectors it protects or promotes, but almost always at the expense of destroying a roughly equivalent number of jobs elsewhere in the economy. At a product-specific or micro level and in the short term, controlling trade could reduce the offending imports and save jobs, but for the economy as a whole and in the long term, this has neither theoretical support nor evidence in its favor. Given that protection may have other—usually adverse—effects, understanding the difficulties in using it to manage employment is important for economic policy.

Key findings

Pros

Protecting import-competing sectors can increase the number of jobs they offer or at least reduce the rate of decline.

Labor market adjustment to a trade reform is slow, so there may be costs to liberalization in the short and medium terms.

A trade liberalization may cause a shift from formal to informal employment, which is often held to be inferior.

Cons

Through its effects on the rest of the economy, the protection of one sector reduces the jobs available in other, export-oriented, sectors.

In the long term, trade liberalizations can boost employment and, other things being equal, more open economies have higher levels of employment.

Trade reform is frequently associated with an increase in the number of “better” jobs.

Trade reform may cause intrasectoral reallocation from less to more efficient firms within sectors.

Author's main message

Trade policy is not an employment policy and should not be expected to have major effects on overall employment. When it does so, it is because it interacts with distortions in labor markets, which vary from country to country and time to time. No generalization is feasible, and seeking to make one is pretty much a fool's errand. Policymakers wanting to boost employment should think about the aggregate economic balance and labor market institutions, and not interfere with international trade.

Motivation

Imports cause job losses in import-competing sectors. They affect the labor market unevenly, across sectors and geographic areas and, because labor mobility is limited, the adjustment process may be very slow. Curtailing imports to preserve jobs seems attractive politics, because it can be presented as politicians protecting (note the word) their constituents from harm produced by adverse foreign forces over which they have no control. This is all very well, but it ignores the effect that protecting Paul has on Peter's ability to earn a living. Through a variety of well-understood mechanisms, protecting some sectors typically harms others and destroys jobs in those other sectors, with the result that one ends up with a distorted economy but little change in overall employment.

Discussion of pros and cons

In the simplest versions of the currently prevailing neoclassical model of the economy, long-term levels of employment and unemployment are determined by macroeconomic variables and labor market institutions, not by trade and not at all by trade policy. So, according to this view, trade policy can have no long-term impact on employment levels. Even neoclassicists, however, recognize that, in the short term, the level of economic activity may be influenced by trade shocks or trade policy changes; they argue, however, that in the absence of other changes, employment will eventually return to its former equilibrium.

The structuralist school, by contrast, rejects Say’s Law that demand expands to absorb supply, and postulates that trade and trade policy shocks can affect employment permanently by creating or destroying jobs with little or no adjustment in the sectors and the regions of the economy not directly affected by the shock [1].

The difference in approach reflects the specific simplifications in different modeling strategies, which in turn stem from different perceptions about the speed of adjustment, the type of frictions slowing down the adjustment, and the appropriate time period to analyze. Neoclassical theory focuses on the longer term. Structuralist theory focuses on time periods short enough that full adjustment has not occurred and is a reminder that, certainly for the people affected, the adjustment path can be sufficiently long and painful to dominate their view of appropriate trade policy.

In fact, the dichotomy need not be as extreme as the previous paragraphs suggest. Theorists have modified the neoclassical model to add in the sort of labor market imperfections that create unemployment even in equilibrium. Introducing efficiency wages and job searches into trade models can lead to multiple equilibria, and predictions about both (un)employment and the welfare effects of trade liberalization become qualitatively ambiguous [2]. In partial empirical support of more general specifications of the trade model, labor turnover and attitudes toward trade liberalization are consistent with the existence of these sorts of frictions over significant periods of time.

Unfortunately the heterogeneity of economies and the difficulties of isolating trade policy from other policies and from the influence of labor market outcomes make simple statistical tests between these two views impossible. So, that leaves partial and approximate results, which in turn leave a great deal of room for judgment by policymakers.

Aggregate employment

The more direct evidence, based on panel data, shows that when trade is driven primarily by Ricardian comparative advantage (based on technological differences between countries), protection increases unemployment rates across countries [3]. Several permanent trade liberalizations reveal a striking difference in the short-term and long-term responsiveness of unemployment to trade liberalization. While the immediate effect of reducing trade barriers tends to be a rise in unemployment, the longer term sees the reversal of this rise and an eventual decline in unemployment. That is, adjustment takes time but, at least in this dimension, offers positive returns in the long term.

Where trade is determined more by differences in factor endowments (the Heckscher–Ohlin framework) than by differences in technology, standard international trade theory predicts that in capital-abundant countries trade liberalization will boost the returns to capital and (in the simplest form of the model) absolutely reduce those to labor (the Stolper–Samuelson theorem). If job search frictions are added to the labor market, that also produces higher unemployment. In labor-abundant economies, labor is the winner from trade liberalization, and the result would be lower unemployment. There is weak evidence for these outcomes, but it is dominated by the results in the previous paragraph.

The pressure to use trade policy to support employment is probably strongest in developed countries, such as those of Europe, and the US. Although trade policy in these economies is of a sectoral nature (using sector-specific trade policies to support employment in, say, agriculture, steel, or textiles), the evidence from capital-abundant countries hints that there may be an aggregate effect, at least for a few years [3].

A prominent case of a large trade shock with labor market implications is the spectacular growth of Chinese exports over the 1990–2010 period. The “China shock” caused extensive job losses in import-competing industries in the US and other high-wage countries [4]. The neoclassical precept that general equilibrium forces would render a trade shock short-lived, is based on the mechanisms of wage and price arbitrage, and labor mobility. These mechanisms would dissipate a local shock nationally, but they have not completely mitigated the China shock in the US. The adverse employment effects of the China shock were concentrated in manufacturing sectors and in the regions where manufacturing firms locate, were long-lasting and did not dissipate nationally through the reallocation of displaced workers. In aggregate, however, the jobs created by the concomitant expansion of exports to both China and the rest of the world, in sectors not exposed to import competition, more than offset the reduction in manufacturing jobs [5].

The key questions for the aggregate outcome, therefore, are not whether import competition destroys jobs in the affected sectors, but whether the associated increase in exports creates a corresponding number of jobs over a reasonable timescale (either for displaced workers or new ones) and whether this is accomplished without significant reductions in wages.

Reemploying displaced workers

The recent evidence from the China shock, as well as other trade liberalization episodes, suggests that labor markets adjust to trade changes very slowly. Imperfect labor mobility across jobs ties workers’ outcomes to their initial industry and region of employment, and implies long-term negative consequences on both employment and earning trajectories of displaced workers [4]. The experience of job displacement, however, varies in important ways depending on workers’ skill levels and education and the industry-specificity of their human capital. Initially, trade shocks seem to affect all workers similarly, but subsequently, being able to move out of the trade-affected sector is important, not least to avoid being hit by further import shocks. High-wage workers seem better able to do so than low-wage workers. Trade induced adjustment problems, finally, do not end when workers find jobs in growing sectors, but persist for those who lose a substantial part of their human capital in the new environment [6]. Human capital specific to the initial industry, in particular to manufacturing, is the main determinant of workers’ adjustment cost to an import shock.

Ultimately, however, the fate of displaced workers is in the hands of labor market institutions. In countries with active labor market policies, such as Denmark, trade shocks cause workers to move out of the trade-affected sectors and to seek further education, thereby potentially upgrading the supply of skill [6]. In Brazil, some of the trade-displaced workers from the formal sector are eventually absorbed by the informal sector, after years spent in non-employment [7]. In South Africa, a country with high unemployment rates, a small informal sector, and strong wage rigidity due to trade unions, workers displaced by trade liberalization saw an increased probability of becoming discouraged searchers (not actively searching but willing to work) or of exiting the labor force entirely (no longer willing to work) [8].

Hitting poor countries

There is no compelling evidence that trade liberalization disproportionately hits the weak and the poor in developing countries. First, workers at lower levels of education appear to be disadvantaged when coping with trade-induced displacement regardless of countries’ levels of development. Second, there are also cases where trade liberalization has produced more or less equal employment effects across all education levels, but worse effects for black/colored workers among the low-skilled ones, such as in the case of South Africa.

Increasing openness

In contrast to the pessimism emerging in the research on the China shock, a macroeconomic study shows that increasing openness lay behind much of the dramatic decline in the natural rate of unemployment in Singapore [9]. Introducing wage bargaining and trade unions into a specific-factors two-sector economy endogenizes the natural rate of unemployment. Between 1966 and 2000—when the openness ratio (the sum of export and import relative to gross domestic product (GDP)) increased from about two to nearly three—the relative prices of export goods increased, and there was a rapid accumulation of capital in the export sector. Both phenomena increased the marginal product (and, hence, the wage) of labor in terms of non-tradable goods and services, and helped to expand overall employment fourfold (as the population doubled).

The direct effects of the accumulation were larger than those of relative prices, although the latter, a natural consequence of trade liberalization, are arguably the key causal factor behind Singapore's experience. Even if entrepreneurs invested first and then sought markets for their goods, as some have maintained, the home market could never have absorbed the increased quantities, so trade liberalization was the key to selling large quantities without having the price fall.

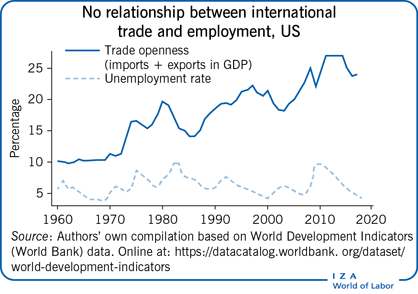

Overall, the empirical results on trade policy and aggregate (un)employment suggest little systematic effect [10]. But there is a tendency for studies relating openness to employment to find a positive relationship between them.

Sectoral employment

Many sectoral studies show that protection for import-competing sectors or export booms for exportable sectors are associated with increases in employment. Translating this into broad-based trade liberalizations that boost both imports and exports would suggest reallocations of labor from the importable to the exportable sectors. Mauritius, during its period of industrialization, 1971–1991, offers some support for this view. Exportable sectors gained employment (and wages), but importable sectors did also, despite the reduction in trade barriers appearing to open them to greater competition. The latter fact can be attributed to the general equilibrium effects of liberalization (and other policies fostering industrialization), which caused the economy to expand strongly. Similar results are found elsewhere for several countries—such as Vietnam.

A less optimistic scenario has been found for Brazil's trade liberalization of the 1990s [7]. The tariff cuts on final goods displaced workers from import-competing sectors, but exporters failed to absorb these workers, even though they expanded their output. The employment losses in tradable sectors were partially offset by transitions into non-tradable employment, although not enough to avoid some workers transitioning into unemployment and eventually into informal employment.

Sectoral reallocation

For developing countries, it is perfectly plausible that both export- and import-competing sectors expand with trade liberalization: industrialization draws workers out of low-level subsistence agriculture and into measurable employment in more easily observed and often more formal sectors. At least at first, this transfer is not curtailed by wage increases. For countries that have already passed the surplus labor stage of development, by contrast, the predicted reallocation, coupled with fairly stationary aggregate employment, is more likely.

Worker migration in response to labor market shocks is very modest, and so it makes sense to expect most sectoral reallocations to be at the level of the local labor market.

Unlike the previous literature, recent research on the impact of the China shock on the local labor markets in high-wage economies does, indeed, show evidence of sectoral reallocation. US imports from China caused job losses in tradable sectors exposed to import competition. These losses, however, were largely offset by US exports to the rest of the world, which created jobs in non-exposed and non-tradable sectors [5]. This latter result can be explained by the increasing number of non-manufacturing jobs in (former) manufacturing firms, driven by high-skill service professions such as design and engineering, or by increased marketing or other management services replacing the physical manipulation of material inputs.

By contrast, trade liberalizations in middle-income countries show much less evidence of sectoral reallocation. The transitions observed are not from import-competing into export-growing sectors, but rather into low-wage service or informal sectors, which are widely perceived as lower quality jobs. These results are a direct challenge to the neoclassical view that the benefits of trade derive from shrinking import-competing production and expanding exportable production. They are explicable by the low geographical mobility of workers, which implies that even if long-term aggregate employment appears unaffected by trade policies, the adjustment process is most likely to be accompanied by a long and painful adjustment process at the level of individual workers (as noted above).

Of course, liberalizations vary in depth, nature, and context, so expectations of finding an ostensibly single uniform effect should not be too high! Did countries with greater labor market flexibility have greater reallocations? Apparently not [11]. But the active pursuit of policies to encourage intersectoral mobility was effective in achieving greater reallocation. Thus, while the failure of the simple theory about trade merely shifting resources between sectors and no more should certainly be noted, it is not clear that the theory's basic insights are flawed.

Intrasectoral reallocations and skill intensity

Recent theory and empirical work by international trade scholars has started to explore intrasectoral responses to trade reforms, which seems to be a perfectly natural outcome once it is recognized that firms differ—firm heterogeneity, in the language of trade scholars. Reallocations of labor occur from weaker to stronger firms, often accompanied by the latter's increased investment, higher productivity growth, and more diligent search for better labor. This allows strong growth in sectoral output without significant increases in sectoral employment. The analysis has also suggested that these interfirm but intrasectoral reallocations are frequently associated with an increased demand for skilled labor relative to unskilled labor.

A seminal study of Mexican firms shows that the export boom that followed the peso devaluation of 1994 induced stronger firms to improve the quality of their products and their workforces, and to pay higher wages [12]. In this study, as in many others, this effect was used to explain the widening skill premium rather than employment levels, but the basic insight clearly translates to employment.

Another study assesses the impact of the creation of a customs union, MERCOSUR, on Argentinean firms [13]. In a model where firms choose between two production technologies that differ in their skill intensity there are three types of firm in equilibrium: the skill-intensive exporters, the unskilled exporters, and the unskilled domestically oriented firms. A tariff reduction in an export market induces more firms to enter and upgrade to the skill-intensive technology, increasing the market share of more productive firms. The gains by these firms and their subsequent investment generate higher demand for skilled workers and increase the skill premium. This forces the least-productive firms to downgrade the skills they seek. Testing this model on Argentinean firm data and exploiting the differential reduction in Brazil's tariffs across sectors shows that small firms downgraded skills, while larger firms upgraded them in response to Brazil's tariff reduction. The net effect on the share of skilled labor is positive and implies that one-third of the increase in the employment share of skilled labor in Argentina between 1992 and 1996 was explained by the reduction in Brazil's tariffs.

Note that the analysis looks at the reduction of protection in Argentina's main export market, rather than in Argentina itself. But it is the nature of trade agreements such as MERCOSUR that in order to win concessions by partners, a country, Argentina in this case, has to offer to reduce its own protection. This will affect import-competing firms, and other results in the literature strongly suggest that increasing competition in these sectors will also tend to favor stronger over weaker firms, and skilled over unskilled labor.

Informal labor

One issue that has attracted policy comment is whether trade liberalization leads to greater emphasis on informal rather than formal labor markets. The question is fraught with difficulties because one needs to have a clear idea about exactly what informality amounts to, which varies by country and study.

Some recent works shed light on the relation between trade policy and the distribution of labor between the formal and the informal sectors. Exploiting variation at the level of local labor markets, Brazil's liberalization of the 1990s has been found to have caused larger increases in the share of informal workers in regions facing larger tariff reductions. This is a long-term effect, whereby the informal sector seems to have acted as a cushion to trade-displaced workers from the formal sector. A similar effect was not found in the case of South Africa, due to the higher rigidity of its labor market and the small size of its informal sector.

A positive export shock can, on the other side, induce a more efficient allocation of resources and spur transitions from the informal to the formal sector. The US-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement led to large (virtually unilateral) reductions in US tariffs on Vietnamese exports which, in turn, led to an increase in the share of formally employed workers in Vietnam [14]. These results are consistent with models predicting intrasectoral reallocations, from less to more productive firms, from shocks which increase aggregate wages: in Vietnam the within-industry effects were largest in manufacturing, which experienced the largest tariff cuts. Younger workers and those in more internationally integrated provinces were the most likely to relocate, which is consistent with lower adjustment costs to trade shocks for workers with relatively lower mobility costs.

Limitations and gaps

This analysis is limited by several factors. But it would be fallacious to conclude—from the fact that the conclusion that trade policy has little effect on employment has technical limitations—that the effect is therefore strong (and of whatever sign one prefers). It is still the case that the best efforts in theory and empirics lead to little expectation from international trade policy for aggregate employment. The limitations include the following:

There is a danger that trade policy is influenced by labor market outcomes (endogeneity), and that that relationship gets mixed in with whatever influence trade policy has on the labor market.

Defining overall trade policy stances and aggregate employment presents challenges. For example, should skilled jobs be viewed differently from unskilled ones?

The assessment of the overall impacts of trade and trade policy has rarely been extended to non-tradable (not directly exposed) sectors, which can suffer through general equilibrium effects.

The external validity of the current literature is far from perfect. Episodes of trade policy change are heterogeneous and are likely to have heterogeneous effects on labor markets, with the latter being driven mostly by underling labor market institutions.

Summary and policy advice

The effects of major trade policy changes on aggregate employment are mixed, although there is evidence that, in the long term, trade liberalizations boost employment (at least in developing countries) and that more open economies have higher levels of employment, other things being equal. Indeed, one can identify cases where trade liberalizations have been followed by very rapid growth in employment. The problem, of course, is that in these cases much more than just trade policy was altered, so attribution is inevitably cloudy.

Protecting import-competing sectors can increase the number of jobs they offer—or at least reduce the rate of decline. But such protection, through its effects on the rest of the economy, is likely to reduce the jobs available in export-oriented sectors.

Trade policy is not an employment policy and should not be expected to have major effects on overall employment. When it does, the reason is that it interacts with distortions in labor markets, which vary from country to country and time to time. While the immediate effect of reducing trade barriers tends to be a rise in unemployment, the longer term sees the reversal of this rise and an eventual decline in unemployment. That is, adjustment takes time, but, at least in this dimension, offers positive returns in the long term.

The key questions for the aggregate outcome are not whether import competition destroys jobs in the affected sectors, but whether the associated increase in exports creates a corresponding number of jobs over a reasonable timescale (either for displaced workers or new ones) and whether this is accomplished without significant harm to wages.

Many studies show that protection for import-competing sectors or export booms for exportable sectors are associated with increases in the affected sectors’ employment. Translating this into broad-based trade liberalizations that boost both imports and exports would suggest reallocations of labor from the former to the latter sectors. Trade reform does not appear to cause large reallocations of labor between sectors, but it may still cause intrasectoral reallocation from less to more efficient firms within sectors. Reallocations of labor occur from weaker to stronger firms, often accompanied by the latter's increased investment, higher productivity growth, and more diligent search for better labor.

The policy message is clear: do not expect international trade policy to have major or even possibly predictable effects on aggregate employment. Policymakers concerned about employment levels should think about the aggregate economic balance and labor market institutions, and not interfere with international trade.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 includes analysis of the China shock and trade liberalization episodes in middle-income countries, providing new evidence on job trajectories of displaced workers and sectoral reallocation. New “Key references” are [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [14].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Mattia Di Ubaldo and L. Alan Winters

Say’s Law

Say's Law is attributed to the French economist Jean-Baptiste Say, who wrote, in A Treatise on Political Economy, 1834, “[a] product is no sooner created, than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value.” The idea is simply that if a product worth $x is produced, a flow of $x revenue is generated. (That is, the value is defined by the flow it generates.) That part of the flow which is spent on inputs that are purchased for the purpose of production, represents a direct demand, and that which is not is paid to the various factors of production (land, labor, capital, taxes) as income. Since income is for spending, these people will demand goods and services from others of that value and so ultimately all $x is reflected in demand.

The term “Say's Law” was coined by John Maynard Keynes who summarized it as saying “supply creates its own demand” and then challenged it on the grounds that income may be saved and this not enter demand. Those who adhere to the Law, however, would argue that savings get re-directed into investment and that eventually even hoarded money gets spent.Say, J.-B. A Treatise on Political Economy: Or the Production, Distribution, and Consumption of Wealth. Grigg and Elliot, 1834.

Ricardian and Heckscher-Ohlin comparative advantage

Comparative advantage is the idea that countries will export goods which they can produce relatively more cheaply than their partners and import those in which their costs are relatively greater (with, possibly, a band of non-traded products in between). The theory was formulated by David Ricardo in 1817 in On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. In his exposition of trade between England and Portugal the differences in relative costs arose from the two countries having different patterns of labor productivity across industries. In modern usage, the term “Ricardian comparative advantage” is applied to any circumstance in which costs differences arise from technological differences in productivity patterns regardless of which factor the differences reside in.

The alternative view of Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin postulates that technology is the same in all countries, but that countries differ in the proportions with which they are endowed with different factors of production. If goods require different factors in different proportions from each other, Heckscher and Ohlin were able to show that, say, a good requiring relatively more labor would be relatively cheaper in a more labor-abundant country in the absence of trade and this would become an export when trade occurred. The term Heckscher-Ohlin comparative advantage is used whenever the differences in relative costs are postulated to stem from countries’ different endowments of factors.Ricardo, D. On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. London: John Murray, 1817.