Elevator pitch

The relationship between technology and employment has always been a source of concern, at least since the first industrial revolution. However, while process innovation can be job-destroying (provided that its direct labor-saving effect is not compensated through market mechanisms), product innovation can imply the emergence of new firms, new sectors, and thus new jobs (provided that its welfare effect dominates the crowding out of old products). Nowadays, the topic is even more relevant because the world economy is undergoing a new technological revolution centred on automation and the diffusion of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Key findings

Pros

Product innovation may imply the emergence of new firms and new sectors and thus new jobs; provided that the welfare effect dominates the substitution effect (novel product innovation).

Price and income compensation mechanisms can counterbalance the initial displacement of workers that occurs following process innovation (direct labor-saving effect).

Disentangling the relationship between new technologies (robots and AI) and the labor market allows to single out a possible job creation effect in the upstream industries, that are the suppliers of new technologies/new products.

Industrial and innovation policies that support genuine product innovation and upstream industries can foster job creation.

Cons

New products may displace old products and so hinder the job-creation effects implied by the diffusion of the new activities (substitution effect).

Process innovation may displace labor and create technological unemployment (direct labor-saving effect).

Market and institutional rigidities can weaken the price and income compensation mechanisms that work to lessen job destruction.

With regard to automation and AI technologies, possible job destruction may occur in the downstream industries (the adopters of new technologies implying process innovation).

Author's main message

Policies that support labor friendly novel product innovation, especially in the high-tech domain as AI, can lead to the emergence of new firms, new sectors and new jobs. Meanwhile, any initial displacement of workers can be countered by indirect price, investment, and income compensation mechanisms that reduce the direct job-destroying impact of process innovation. Given this framework, in the face of AI revolution, policy makers should support the industries providing the new technologies where job creation is more likely, while social safety nets should be designed for possible job losses in the downstream industries adopting AI and automation technologies.

Motivation

The relationship between technology and employment has long been a subject of debate. Claims of technologically-caused unemployment tend to re-emerge at times of radical technological change such as countries are currently experiencing, facing the arrival of automation and AI technologies.

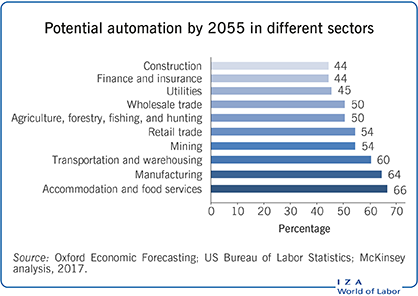

Today, debate focuses on three main questions: What are the roles of technology and innovation in explaining the long-term declining trend of manufacturing as a share of the modern economy? Are new technologies, such as robots and artificial intelligence, replacing humans? Are job losses due to the advent of robots and AI structural and therefore inevitable?

Discussion of pros and cons

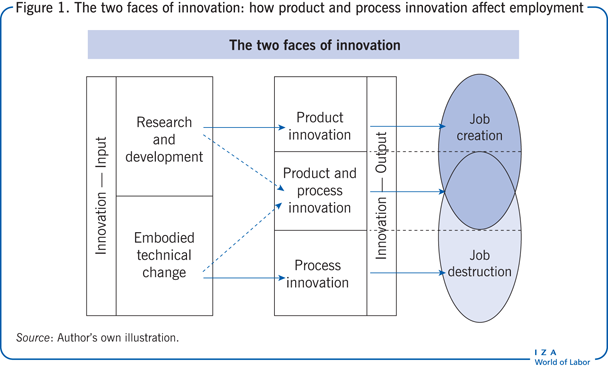

Referring to the theory put forward by the economists of innovation, there are two basic innovation inputs: research and development (R&D), which may lead to product innovation, and embodied technological change, which may lead to process innovation. R&D investments are the key innovation input in the approach originally proposed in 1979 by Zvi Griliches, who identified the concept of the “knowledge production function” [1]. In this functional relationship linking innovative inputs to innovative outputs, firms pursue new economic knowledge as an input into generating innovative activities. Meanwhile, embodied technological change involves process innovation, or innovation that is incorporated in investments in capital goods (machinery and equipment, for instance robots and other automation devices).

However, in some circumstances, the distinction between product innovation and process innovation is ambiguous from an empirical point of view (consider, for instance, the diffusion of information and communication technology (ICT) in the past decades, and artificial intelligence nowadays), and in many cases the two forms of innovation are interrelated as both innovation inputs and innovation outputs. Figure 1 illustrates the main links between innovative inputs, innovative outputs and their eventual impact on the labor market.

As a preliminary approximation, the direct impacts of process innovation and novel product innovation involve different employment impacts (as shown in the far-right panel of Figure 1. On the one hand, process innovation results in a direct labor-saving (job-destroying) effect, related mainly to the introduction of machinery and equipment that can substitute for labor. On the other hand, R&D and product innovation can entail a job-creating effect through the emergence of novel products and new markets. However, process and product innovation can be interlinked (see the dot lines and the grey area in Figure 1) and the same device can be a product innovation in an upstream industry and a process innovation in a downstream sector. For example, the design and implementation of a new AI algorithm is a novel product innovation in the supplier industries and may entail job creation (e.g. an increase in the demand for data scientists). However, the same algorithm may imply job losses when is adopted in the user sectors as a process innovation (e.g. a drop in the demand for bank clerks).

The labor market implications of process Innovation

Since process innovation means producing the same amount of output with less labor, the direct impact of process innovation is job destruction if output is fixed. However, economic analysis has demonstrated the existence of countervailing economic forces that can compensate for the reduction in employment arising from technological progress. Classical economists put forward a theory that Marx later called the “compensation theory.” Technological change can trigger various market compensation mechanisms that can counterbalance the initial labor-saving impact of process innovation [2], [3]. These compensation mechanisms include new machinery, lower prices, new investments, and lower wages.

The compensation mechanism via new machinery

The effect of the compensation mechanism operating through new machinery is ambiguous. On the one hand, process innovations displace workers in downstream industries that introduce the new machinery (for instance robots and other automation devices). On the other hand, additional workers are needed in the upstream industries that produce the new machinery.

However, there are at least three arguments against the efficacy of this compensation mechanism. First, for the introduction of the new machinery to be profitable, the cost of labor associated with the construction of the new machinery has to be lower than the cost of labor displaced by the new capital goods. Second, labor-saving technologies spread to the capital good sectors as well (robots producing robots). Third, and most important, the new machinery can be implemented through either new investments or by the replacement of obsolete machinery (scrapping). In the case of scrapping, which is the most common way through which embodied technological change is implemented, there is no compensation at all for the resulting job losses.

The compensation mechanism via lower prices

While process innovations destroy jobs, the changes that they introduce lead to declining average costs. Assuming perfect competition, this effect is translated into lower prices, which in turn imply rising demand and therefore additional production and employment.

However, this line of reasoning does not take into account possible demand rigidities. For instance, pessimistic expectations by firms may delay expenditure decisions, resulting in lower demand elasticity. In that case, the compensation mechanism of lower prices fails to operate as expected, and technological unemployment becomes structural.

Finally, the effectiveness of the mechanism that plays out through lower prices depends on the assumption of perfect competition. In an oligopolistic market, that is a market with few sellers and many consumers, this compensation mechanism is severely weakened since cost savings are not necessarily or entirely translated into lower prices.

The compensation mechanism via new investments

If the assumption of perfect competition is dropped, the innovative firm can reap extra profits. If these extra profits are re-invested, this investment can create new jobs.

However, this compensation mechanism through new investments is based on the strong assumption that accumulated profits due to innovation are entirely and immediately translated into additional investments. In fact, because of pessimistic expectations, a firm may decide to postpone any new investment. In that case, again, a substantial delay in the realization of this compensation mechanism may imply structural unemployment.

Moreover, the nature of any new investment is important. If investments are capital- rather than labor-intensive, compensation for job losses through investment can only be partial.

The compensation mechanism via declining wages

In a partial equilibrium framework that considers equilibrium of demand and supply only within the labor market (rather than dynamically, within the economy as a whole), the direct effect of labor-saving technologies may be compensated for within the labor market itself. Under the assumption of full substitutability between labor and capital, technological unemployment leads to a decline in wages, and this impact in turn induces a shift back to more labor-intensive technologies.

However, countering this compensation mechanism of falling wages is the Keynesian theory of “effective demand.” While falling wages might be expected to induce firms to hire additional workers, it may also be the case that the shrinking of aggregate demand as a result of falling wages could lower employers’ business expectations and so their willingness to hire additional workers.

Moreover, this compensation mechanism assumes perfect substitutability between capital and labor, which is often not the case, especially under conditions of cumulative and irreversible technological progress.

On balance

The market compensation mechanisms discussed above emerge as powerful forces counterbalancing the initial job destruction impact of process innovation. However, the functioning of These mechanisms is hindered by many institutional and market failures that can greatly weaken their efficacy. Eventually, determining how effective these mechanisms are is a matter for empirical analysis (see below). Interestingly enough, this “classical” theoretical framework is still a proper theoretical benchmark to assess the eventual employment impact of the new technologies brought about by the AI revolution.

Product innovation

Obviously, the introduction of new products and the consequent emergence of new markets may involve job-creation effects. Consider, for example, how many direct and indirect jobs were created as a result of the invention of the automobile at the beginning of the 20th century or of the personal computer later in that century. Nowadays, AI devices conceived as product innovations in the upstream industries may also entail job creation.

The compensation mechanism via the welfare effect

However, from a theoretical point of view, the labor-friendly impact of product innovation may be stronger or weaker, depending on some circumstances and general equilibrium effects. Indeed, the “welfare effect” of novel product innovation (that is the possible labor-friendly impact involved by the emergence of genuine new products, new industries, and new demand) needs to be assessed against the “substitution effect”, that is the displacement of mature products by new ones (think, for instance, how smartphones have replaced cameras, music players, fax machines, and even computers) [4]. In this respect, the welfare effect can be considered as a compensation mechanism of the crowding out of old products and industries.

Current debate

Nowadays, a theoretical revival simplifies all the compensation mechanisms discussed above. This vision puts forward opposing forces affecting the relationship between innovation and employment [5]. The first force assumes that job tasks can be automated depending on factor prices and the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor (displacement effect). The other forces point to counterbalancing mechanisms that may offset the displacement effect. The first “self-correcting” force is the productivity effect involving the compensation mechanism via lower prices discussed above. The second “self-correcting” mechanism is called “capital accumulation,” which is very similar to the compensation mechanism via new investments, also discussed above. Finally, the third “self-correcting” force is the reinstatement effect, which implicitly refers to the compensation mechanism operating through the emergence of novel products and new industries. Similar to the compensation mechanism theory, the efficacy of these mechanisms depends on many institutional and market forces that can significantly weaken them (see above).

The accomplishment of all mechanisms mentioned before is doubtful, especially because they depend on several factors, assumptions, and elasticities. This implies that economic theory is inconclusive about the relationship between employment and technological change. However, theoretical models can be complemented by empirical analysis to understand the phenomenon better.

Empirical evidence at the macro, sectoral, and firm Level

Very few macroeconometric studies have tried to test the validity of compensation mechanisms through aggregate empirical studies conducted within a general equilibrium framework. One study estimated the direct labor-saving effect of process innovation, various compensation mechanisms (with their transmission channels and their possible drawbacks), and the job-creating impact of novel product innovation for two advanced Western economies, Italy and the US, over 1960–1988 [2]. This study finds that the most effective compensation mechanism for limiting employment losses in both countries was falling prices; other mechanisms were less important. Moreover, the US economy was more product-oriented, as evident in an overall positive relationship between technological change and employment, than the Italian economy, where the various compensation mechanisms were unable to counterbalance the direct labor-saving effect of widespread process innovation.

A more recent study uses the number of triadic patents (a set of linked patents at the European, Japanese, and US patent offices) in 21 industrial countries issued over the period 1985–2009 as an innovation indicator for assessing the impact of innovation on the aggregate unemployment rate [6]. The results show that technological change tends to increase unemployment, although this effect does not persist in the long term.

In principle, the ideal setting to fully investigate the link between technology and employment is a macroeconomic empirical model that jointly considers the direct effects of process and product innovation and all the indirect income and price compensation mechanisms discussed above. In practice, however, such empirical macroeconomic exercises are very difficult to arrange. They are also controversial, for several reasons. First, measuring aggregate technological change is problematic. Second, the analytical complexity required to represent the various compensation mechanisms makes interpreting the aggregate empirical results extremely complicated. And third, composition effects (in terms of sectoral input–output linkages) and the behavior of individual firms may render the macroeconomic assessment unreliable or meaningless. For these reasons, and because of the recent availability of reliable longitudinal data sets, the sectoral and microeconomic literature on the link between innovation and employment is larger and flourishing.

In manufacturing, a study for eleven European countries (1998-2011) finds a job-desctruction impact of capital formation (as a proxy of process innovation) due to the embodied technological change incorporated in gross investement and a siginifcant job-creation effect of R&D expenditure (especially in medium- and high-tech sectors) [7].

Other studies analyze the effects of the innovativeness of upstream and downstream sectors on employment. In the first case, using sectoral data from 19 European countries from 1998-2016, the study assumes that upstream sectors pursue R&D activities while downstream sectors invest to replace or expand fixed capital. The main findings are a negative effect of capital replacement and a weaker positive effect of expansionary capital investment. Also, the job-creation labor effect of R&D is found, but it is weakly significant [8]. Although this study does not explicitly refer to AI technologies, its theoretical framework can be used as a benchmark for assessing the controversial employment impact of robots and AI. According to this model and its econometric test, new technologies should imply significant job losses in the downstream sectors (adoption of AI and robots) and a (weaker) job creation in the supply upstream industries.

Several recent microeconometric studies have fully taken advantage of the newly available longitudinal data sets to apply panel data econometric methods that jointly take into account both the time dimension and the cross-section firm-level variability. There are two main empirical frameworks at the micro-level of analysis. The first one is the input-oriented model, where the proxy of innovation, most of the times, is R&D expenditure as product innovation and gross capital investment (embodied technological change) as process innovation. The second one is the output-oriented model, where the proxies of innovations are sales growth due to new products (product innovation) and sole process innovation (the process innovation not associated with product innovation) [9].

The first study to use the input-oriented model matches the London Stock Exchange database of manufacturing firms with the innovation database of the Science Policy Research Unit at the University of Sussex (SPRU) to create a panel of 598 British firms over 1976–1982 [10]. The study finds a positive employment impact of innovation, a finding that remained even in several variations of the model specification.

Another interesting study that uses a panel database covering 677 European manufacturing and service firms over 19 years (1990–2008) detectes a positive and significant employment impact of R&D expenditures only in services and high-tech manufacturing but not in the more traditional manufacturing sectors [11]. In the more traditional manufacturing sectors, the employment effect of technological change is not significant.

More recent studies for European countries, using longitudinal data and a better measure of embodied technological change, found the labor-friendly nature of R&D expenditures but a possible overall labor-saving impact of embodied technological change [12].

The first study that applies the output-oriented model uses firm-level data obtained from the third wave of the Community Innovation Survey for France, Germany, Spain, and the UK [13]. This study comes to the conclusion that process innovation tends to displace employment, while product innovation is basically labor-friendly (see also [4]). This approach has been widely applied in developing and developed countries and different sectors (manufacturing and services, high-tech and low-tech). A meta-regression analysis of 27 studies that applies this output-oriented approach suggests that the employment impact of sales growth due to new products is positive and homogeneous, being a good proxy for product innovation. In contrast, the negative labor effect of the dummy “sole process innovation” is very heterogeneous, and its magnitude and statistical significance depend on various circumstances (for instance, developing vs. developed countries, sectors, period of crisis, different methodologies). One of the main critique addressable to this bunch of studies is that the dummy variable “sole process innovation“ fails to fully capture firm’s process innovation strategy [9].

The emergence of the new technological paradigm has generated a desire to explore the empirical effect of specific technologies (e.g., robots and artificial intelligence) on the labor market. In the case of robots, studies at the industrial level that use data from the International Federation of Robotics and EUKLEMS, the EU level analysis of capital (k), labor (L) energy (E) materials (M) and services (S), for developed countries have found a negative effect on employment (specifically for low-skilled workers and in services sectors) [14], [15]. The contrary happens with studies at the firm level, in which most studies find positive impacts of robots on employment (see, for instance: [16]). However, optimistic employment results obtained at the firm-level of analysis can be entirely due to the “business stealing effect” (innovative firms, being more competitive, gain market shares at the expenses of the laggers) and job creation at the firm level can well cohexist with job destruction at the industry level [17].

New empirical methodologies (such as natural language processes and text analyses) allow to explore other sources of information (e.g., job posts and patents). These types of studies analyze the exposure and the impact of artificial intelligence (robots) on the labor market. Also, these types of studies can assess the proximity between specific innovations, occupations, and tasks. For instance, one study tries to look at AI-exposed establishments by combining job posts using Burning Glass Technology data and Standard Occcupational Classification (SOC) codes. The study finds no apparent effect at the industry and occupational levels, but it does find a re-composition toward AI-intensive jobs [18]. Other studies using patents (AI-related inventions) show a moderative positive employment impact of AI patenting within the industries which patent in AI, that is the upstream sectors which provide the new technologies (see above) [19].

Other approaches distinguish between labor-saving innovations and labor-complementary technologies. A study identifies labor-saving innovations using textual analysis of US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) patent applications in robotics. The main results show that some activities are more exposed to labor-saving innovation, such as those related to transport, storage, packaging, and moving objects [20].

Limitations and gaps

Theoretical models cannot claim to have a clear answer on the final employment impact of process and product innovation.

While the price and income mechanisms described here have the potential to compensate, fully or in part, the direct labor-saving impact of process innovation, the precise outcome is uncertain. Determining factors include such variables as the degree of competition, demand elasticity, elasticity of substitution between capital and labor, and expectations of consumers and employers. Overall, depending on market structure and institutional contexts, compensation mechanisms can be more or less effective, and the unemployment impact of process innovation can be totally, partially, or not at all neutralized.

Similarly, the findings of empirical studies are not fully conclusive about the possible employment impact of innovation and technological change. Most recent panel investigations support a positive link. This positive link is especially evident when R&D or product innovation are adopted as proxies for technological change and when the focus is on high-tech sectors and high-growth firms. In many sectors, however, especially in services, product and process innovation are intermingled and difficult to disentangle. Therefore, it is not always easy and straightforward to design industrial and innovation policies that can effectively maximize the positive employment impact of innovation.

With specific regard to the AI technologies, the scarce available evidence suggests that technological leaders within the emergence of the AI paradigm can realize (moderate) labor-friendly outcomes; however, other companies (particularly in manufacturing) may reveal to be unable to couple product innovation with job creation.

Moreover, compared with the labor-saving impact implied by the adoption of AI and automation technologies (massive according to some studies, see above), the labor-friendly extent in the supply industries appears limited in magnitude and scope (just as a narrative example: the hiring of data scientists in upstream services and AI big-tech would hardly compensate job losses due to robots in downstream manufacturing).

As a gap in the current literature, much is needed in terms of additional empirical evidence able to compare the actual magnitude of possible complementary effects within the providers of new AI technologies with the possible job-losses due to the substitution effects within the users of new AI and automation technologies.

Summary and policy advice

A clear policy implication derivable from the discussion conducted so far would seem to be that economic policy should try to foster job creation by supporting R&D investments and novel product innovation. In the AI era this means to foster emerging industries and innovative start-ups, active in AI design, engineering, and patenting.

However, the picture is more complicated than that. Firstly, product and process innovation are often interrelated; secondly, process innovation does not always leads to job destruction (see the classical compensation theory and its recent revival discussed above); thirdly, product innovation not always involves job creation (when the welfare effect is weak, compared to the crowding-out of older products). This means that the policy implication proposed above should be carefully articulated and tailored.

A general theoretical conclusion is that compensation mechanisms are always at work but that the full reabsorption of workers dismissed as a result of technological change cannot be assumed ex ante. In particular, to work properly, compensation mechanisms require competition (to facilitate the compensation mechanism that works through lower prices), optimistic expectations (to facilitate the compensation mechanisms that work through lower prices and new investments), and a high elasticity of substitution between capital and labor. In this framework, competition policies that lower entry barriers and reduce monopolistic rents, along with expansionary policies targeting intermediate and final demand for novel products, can be important drivers of job creation. In this respect, the concentration of AI research and patenting in the hands of the ICT “big tech” is extremely worrying and should be contrasted by a fierce antitrust policy (for instance, through limiting Intelecutal Property Rights (IPRs) and extending open source; fighting concentration and acquisition of innovative startups; regulating the ownership of big data and the scope of platforms).

Moreover, the general equilibrium market mechanisms often operate at the inter-industrial and the inter-occupational level, implying the need for labor mobility and re-skilling, since new technologies are associate to different and novel tasks. While this was the case in the past as well (see, for instance, the displacement of telephone operators in the ‘20s and ‘30s), it is particularly crucial nowadays with regard to automation and AI technologies. Indeed, although being in their initial stage of diffusion, current technologies exhibit a large potential in terms of a radical reshuffle of the demand for labor in terms of the required tasks and occupations (involving challenging consequences in terms of skill obsolescence, need for creativity, decline of boring and repetitive tasks and emerging of novel and interesting ones, etc.). As a policy implication, these circumstances call for proper education and training policies.

Turning attention to the available empirical evidence, the most recent microeconometric analyses tend to support a positive link between technological advances and employment, especially when the focus is on R&D, product innovation and upstream high-tech firms. These positive employment outcomes of evidence-based studies are consistent with a lifecycle view of different industries, with emerging sectors characterized by product innovation (mostly labor-friendly) and more traditional, mature industries more likely to experience process innovation (mostly labor-saving). As a policy implication, policy makers should foster the emergence and the strenghtening of upstream AI-intensive industries, where the job creation impact is concentrated.

However, both industrial and innovation policies need carefully to take into account a series of complex interactions between process innovation and product innovation, between mature sectors and new sectors, and between job-creation effects in the upstream industries and job-destruction effects in the downstream industries. For instance, safety nets and active labour market policies are necessary to deal with the employment displacement due to the widespread diffusion of AI and automation technologies in the user industries. In more general terms, an economic policy aiming to maximize the employment impact of new technologies should be selective, granular and targeted to specific novel products and emerging industries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the authors contains a large number of background references for the material presented here and has been used in some parts of this article. Version 2 of this article includes latest developments with respect to AI and robots, it adds a new figure, new Further readings, Additional references, and Key references [1], [4], [5], [7], [8], [9], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], and [20].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The authors declare to have observed these principles.

© Marco Vivarelli and Guillermo Arenas Días