Elevator pitch

Conventional wisdom and prevailing economic theory hold that the new owners of a privatized firm will cut jobs and wages. But this ignores the possibility that new owners will expand the firm’s scale, with potentially positive effects on employment, wages, and productivity. Evidence generally shows these forces to be offsetting, usually resulting in small employment and earnings effects and sometimes in large, positive effects on productivity and scale. Foreign ownership usually has positive effects, and the effects of domestic privatization tend to be larger in countries with a more competitive business environment.

Key findings

Pros

State ownership and central planning are generally thought to be associated with excess employment.

Soft budget constraints and lack of competition under state ownership may lead to rents for incumbent employees.

Private owners are likely to aim for profit maximization rather than political objectives; they may have access to skills, markets, and technologies that increase output, employment, and productivity.

Productivity increases may lead to wage increases.

Positive effects are more likely the larger the scale and productivity effects, which may be greater under experienced, skilled investors in better business climates.

Cons

Budget constraints are not infinitely soft, so state-owned firms have some incentives to economize.

Negative consequences for employment and earnings are larger where state-owned firms are most protected, regulated, and subject to planning.

The business environment and intensity of competition matter regardless of ownership.

Limited evidence suggests that wage and employment losses are greatest for low-skilled workers.

Author's main message

Until recently, employment and wage effects of privatization received little attention in empirical research. None of the conducted studies show large negative effects on either employment or wages. Recent research in transition economies using much larger panel data that enable use of more appropriate evaluation methods confirms this finding and also reports systematically better outcomes for workers under foreign than domestic privatization. The policy implications are potentially profound. Despite the likely performance benefits, policymakers may be reluctant to privatize because of fears of job losses and wage cuts. The findings that average employment and wage losses tend to be low and that effects are sometimes positive should alleviate those fears.

Motivation

Although economic analyses of the effects of privatizing state-owned enterprises have focused largely on firm performance, the greatest political and social controversies have usually concerned the consequences for a privatized firm's employees. Most observers and participants assume that the employment and wage effects of privatization are negative. Workers around the world react with protests and strikes to the prospect of privatization, especially when foreign owners may be involved. Theoretical models of privatization arrive at the same conclusion, with efficiency-minded new owners predicted to restructure at the expense of employees. Yet until recently there has been little systematic empirical evidence on the relationship between privatization and outcomes for a firm's workers, and research has been hampered by small sample sizes, short time series, and little ability to control for selection bias. Thus, it has been unclear whether workers’ and policymakers’ fears of privatization are in fact warranted.

Discussion of pros and cons

Standard economic models of privatization

Standard economic models of privatization imply that new private owners raise productivity and reduce costs, potentially resulting in job losses and wage cuts for workers [2], [3]. However, discussions of these productivity-improvement and cost-reduction effects of privatization implicitly assume that the firm's output remains constant [1].

For a given output level, an increase in labor productivity necessarily implies a reduction in employment. But if cost reduction leads to an increase in quantity demanded or if the new private owners are more entrepreneurial in marketing and entering new markets, then the firm's sales and output may expand. This scale effect of privatization will tend to increase employment, thus working in an opposing direction to the productivity effect. If the scale effect dominates, the net result could be a rise in employment [1].

What about the effect of privatization on wages? The standard theoretical models imply that the new private owners will reduce the rents (earnings beyond the level necessary to induce workers to accept the job) earned by employees in the state sector. The new owners may also break implicit contracts and expropriate quasi-rents (returns to specific investments by workers), as in hostile takeovers. However, the cost-reduction effect may be lessened if privatized firms pay higher wages to attract new workers or to elicit greater effort from workers. Private firms may earn and share higher rents, while productivity improvements imply higher wages for given unit labor costs. Depending on the relative strength of these factors, wages may either rise or fall as a result of privatization [1].

Other factors may also alter the effects of privatization. The extent to which state enterprises function with profit-oriented objectives may vary, and the firms may be subject to disciplinary forces through the business environment and the intensity of competition. Also important is the degree to which new private owners bring access to technologies, skills, and markets that imply expansion of output and employment. Any negative consequences for employment and earnings are likely to be larger when state-owned firms are most protected.

The effect of privatization on employment and wages

Not only does the theoretical analysis fail to provide definitive predictions on the employment and wage effects of privatization, but the existing empirical evidence is limited [1]. That is in sharp contrast with the extensive literature on privatization and firm performance and workers’ well-known fears of privatization. One study argues that US public sector employees oppose privatization because they expect it to result in lower wages and job losses. Unions have frequently protested planned privatizations; examples from France include, France Telecom and Gaz de France.

Much of the small body of research on the effect of privatization on employment and wages is flawed because of small sample size, short time series, and difficulty defining a comparison group of firms. The data limitations have not only reduced the generality of the results but have also constrained the use of methods that could account for selection bias in the privatization process. The first systematic study of the effects of privatization on employment and wages, for example, analyzes 14 publicly owned British companies, of which four were privatized and the others were deregulated [4]. Another study uses data for 1983 and 1988 to estimate the employment effects in 62 Bangladeshi jute mills, half of which were privatized [5]. And a study of 170 privatized firms in Mexico has just a single year of post-privatization data for analysis [6].

Some studies expand sample sizes by using data on individual employees, but the data sets also contain few cases of privatized firms. For instance, a study using a five-year panel of personnel records of a single large Swiss public sector telecommunication company shows that privatization resulted in an average wage decrease as well as increased wage inequality after the introduction of a private sector wage scale [7]. Two other studies of around 300 privatizations in Portugal find positive wage and negative employment effects [8], [9]. Following workers employed in 339 privatized firms in Sweden, another study provides evidence that privatization has no effect on wages, while it leads to an increase in the incidence and duration of unemployment.

While all of these studies offer useful analysis, the small number of privatizations in their data tends to limit their generalizability and the extent to which they can use appropriate econometric methods. Perhaps as a consequence, the overall results from this earlier research on privatization and employment and wages are inconclusive, obtaining both negative and positive estimates of the effects on workers.

Other studies have sometimes included employment as one of several indicators of firm performance, but not as the focus of analysis. Of six studies of firm performance that also consider employment effects, two find a positive effect of privatization on employment, three no effect, and one a negative effect.

More recent research that uses much larger samples of firms provides stronger evidence on the employment and wage effects of privatization [1]. For Hungary, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine, available data include nearly the universe of manufacturing firms inherited from central planning, both those eventually privatized and those remaining under state ownership. The time series data run from the communist and immediate post-communist period, when all firms were state-owned, through 2005, well after most had been privatized. The four countries span the range of approaches to privatization methods and reform experiences among transition economies, with Hungary considered one of the most successful, Russia and Ukraine among the least successful, and Romania in the middle. For each firm in each country, comparable annual data are available on average employment and the total wage bill. The ownership data allow distinctions between foreign and domestic ownership types and inferences on the precise year in which the ownership change occurred.

The data for Hungary, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine also enable the creation of comparison groups of state-owned firms operating in the same industries as those privatized, while the long time series permit the use of econometric methods developed for dealing with selection bias in labor market program evaluations.

Foreign versus domestic private ownership

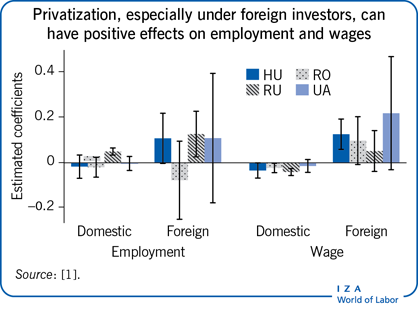

The results from this analysis show no large negative impacts of privatization on either employment or wages [1]. Estimated employment effects are never both negative and statistically significant, while the estimated wage effects are significantly negative only for domestic privatization in Hungary and Russia, but the effects are small in both countries (–3% to –5%) (Illustration). The estimated coefficients on foreign ownership contrast strongly, with signs that are uniformly positive for both employment and wages in all four countries. The results show that downsizing and wage cuts rarely occurred in these economies before privatization. The results are also inconsistent with spillovers to the state sector, which would imply temporary effects that disappear in the longer term.

Therefore, the results for domestic privatization imply only small changes in these variables, relative to the state-owned comparison group, while the data provide evidence of positive impacts of foreign privatization on employment and wages [1]. The lack of impact for domestic privatization might imply that the new domestic owners have little effect on firm behavior.

Productivity and scale effects

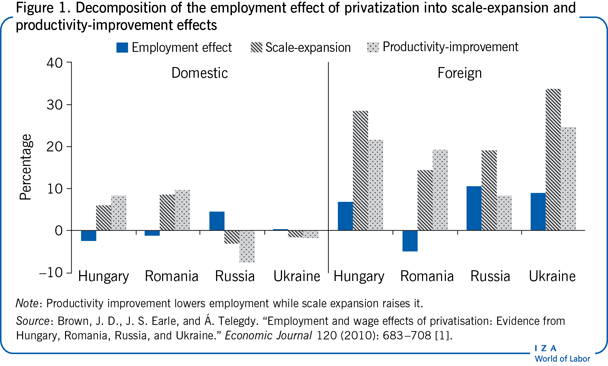

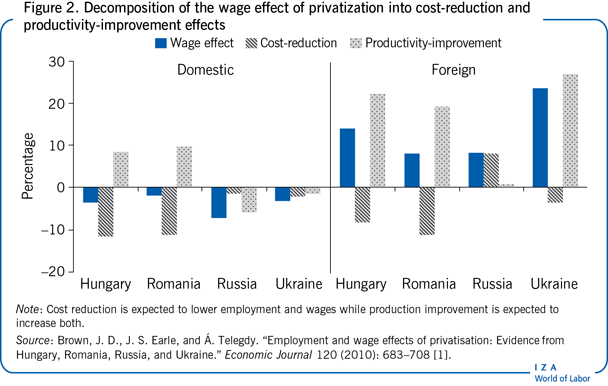

Another possibility is that firm behavior changes in ways that have opposing effects on employment and wages. To examine this question, it is possible to decompose the estimated employment impact into a “productivity-improvement effect” that tends to lower employment for a given output and a “scale-expansion effect” that tends to raise it, holding productivity constant (Figure 1). The wage impact of privatization is decomposed into “cost-reduction effects,” expected to have negative effects on employment and wages and “productivity-improvement effects,” expected to have positive effects (Figure 2).

The results from these analyses contradict the view that domestic privatization has little effect on firm behavior. Instead, the results show that domestic privatization tends to produce gains in both scale and productivity that offset each other in their employment outcomes and to produce cost reductions and productivity improvements that have offsetting effects on wages. In Hungary and Romania, the scale, cost, and productivity effects of domestic privatization have all been large, while in Russia and Ukraine they have all been small [1]. Foreign privatization has resulted in much larger scale, productivity, and cost effects in all four countries, but the scale effects dominate the productivity effects, which in turn dominate the cost effects. The results are increased relative employment and wages in foreign firms that are observed after privatization. These patterns of effects are plausibly tied to the quality of corporate governance resulting from different methods of privatization, as well as differences in the business environment.

Worker and job turnover and wages

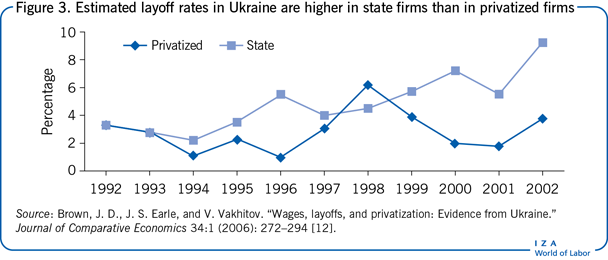

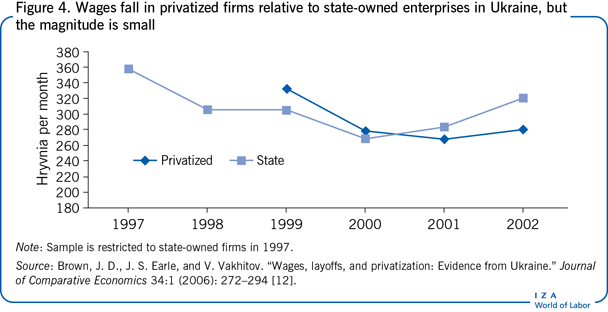

Worker and job turnover issues, including layoffs and hiring, and other labor market adjustments such as hours of work have also received less attention than the overall employment effects. A few studies contain some analysis of job and worker turnover and privatization in Russia. A study of job creation and destruction in Russian manufacturing finds little difference in the rates of these flows in privatized companies compared with in state-owned enterprises [10]. A study that focuses on worker turnover finds no evidence of a negative impact of privatization on either employment changes or dismissals [11]. Another study analyzes layoffs and wages in Ukraine, finding a sizable negative effect on layoffs and a small negative effect on wages [12]. From December 1991, shortly after the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine became independent, to 2002, estimated layoff rates are always higher in state firms than in privatized firms (Figure 3). In a regression with control variables, the difference amounts to about 50%.

In the same study, a worker-level analysis of the wage effects of privatization over 1998–2002 finds that wages fall in privatized firms relative to state-owned enterprises, but the magnitude is small; with regression controls the estimated wage effect is –5% (Figure 4).

Variation in effects of privatization for different types of workers

Studies using firm-level data to estimate the effect of privatization cannot control for worker-level characteristics and account for the composition of the workforce. This omission may be particularly problematic if the changes in ownership are correlated with changes in workforce composition. Using linked employer-employee data from Hungary, one study shows that composition of the workforce varies significantly by ownership type: workers with longer potential experience and only basic education tend to be employed in the state sector while having vocational education is correlated with the probability of being employed in the domestic private sector; female workers and those with a university education are more likely to work in foreign firms [13]. But the study finds that controlling for workforce composition does not change conclusions about the impact of privatization on workers.

Another limitation of firm-level studies is their inability to estimate distributional wage and employment effects. A small number of studies using linked employer-employee data show that labor market effects of privatization vary significantly by demographic characteristics and skill level. Limited evidence implies that high-skilled workers tend to be the winners of privatization, experiencing the largest increase in wages and lowest likelihood of being out of the labor market [8], [12], [14]. A possible reason why high-skilled workers disproportionately benefit from privatization could be that ownership change is related to investment in new technologies that are likely to be complementary to the employment of high-skilled workers [14].

The findings are less clear about gender differences in the privatization wage premium. While a study on privatization in Ukraine finds no gender differences in post-privatization wages and layoffs [12], the results of an analysis of Swedish data imply that women are relative beneficiaries of privatization, earning higher labor income and are less likely to be out of the labor force [14]. Another study, alternatively, finds higher wage losses for women following contract liberalization in a large public sector company in Switzerland [7].

Tenure is another worker characteristic that may be related to gains or losses from privatization. Again, the few studies available provide only limited evidence. In Sweden, where tenure is related to employment protection status, workers with longer tenure are found to experience a lower likelihood of being fired and have lower losses of labor income [14]. More generally, tenure and age tend to be the basis for promotion in the public sector where older workers with high tenure are more likely to be promoted. Privatization thus gives low-tenured and younger workers more opportunities to be hired and earn higher salaries in the post-privatization period [9], [10].

Limitations and gaps

Much more limited than the research on average employment and wage effects is the evidence on other aspects of worker welfare, such as fringe benefits and other work conditions that could well change with ownership. The available data contain little information on these noncash aspects of work, and although it seems likely that they would be positively correlated with wage effects, the possibility that privatization affects the cash-noncash compensation mix cannot be excluded.

While worker turnover has received some attention, there is essentially no evidence on the fate of displaced workers from privatized firms—for instance, on how quickly and at what wages they become re-employed. A study of displaced workers in Russia was unable to distinguish privatized state enterprises from new private firms, which is necessary to draw inferences about the effects of privatization. Nor is there evidence on whether newly hired workers at privatized firms are new labor force entrants or workers pulled from state enterprises or other privatized firms. Particularly relevant would be estimates of the degree to which newly hired workers at privatized firms experience wage gains relative to what would have happened had the firms not been privatized. Again, evidence is lacking.

The focus here on direct effects has also omitted any spillover effects (general equilibrium effects) that could be relevant to a welfare evaluation of privatization. For example, if privatization improves firm performance, it might reduce employment and wages at competitor firms or raise them at upstream supplier firms. Privatization may also have spillover effects through the general business environment. None of these questions has received systematic analysis.

Another limitation of current knowledge concerns the effects of different privatization methods and resulting ownership structures. The fairly uniform results across countries, at least in the sense that no country shows evidence of large negative employment or wage effects, is suggestive. But the data do exhibit some variation, with clear positive effects in some countries and essentially zero effects in others.

Even for the average effects of privatization on employment and wages, the evidence is limited to a small number of countries and largely to firms in the manufacturing sector. A broader understanding of the consequences of privatization requires more analyses of high-quality data sets in multiple countries with more outcome variables and particularly with longitudinal employer-employee information.

Summary and policy advice

Although economic analyses of privatization have focused largely on firm performance, the more controversial question has often concerned the effects on firms’ employees. Both policymakers and scholars seem to assume that the employment and wage effects are negative, and workers around the world react to the prospect of privatization with protests and strikes, especially when foreign owners may become involved [1]. Until recently, these assumptions had not been subject to thorough examination. Early research was hampered by small sample size, short time series, and limited ability to control for selection bias. It was therefore unclear whether workers’ and policymakers’ fears of privatization were in fact warranted.

Recent research using much larger data sets over longer periods of time in Hungary, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine provides a better basis for assessing the employment and wage impacts of privatization. The results provide no evidence for strong negative effects of any form of privatization on either employment or wages [1]. Estimated employment effects are never both negative and statistically significant, while the estimated wage effects are sometimes significantly negative only for domestic privatization in Hungary and Russia, but the effects are small in both countries (–3% to –5%). The estimated coefficients on foreign ownership contrast sharply, with effects that are nearly always positive in all countries for both employment and wages [1].

There is also some evidence on three channels through which privatization may affect outcomes for workers: productivity-improvement, cost-reduction, and scale-expansion effects. Decomposing employment effects into scale and labor productivity effects shows that domestic privatization has tended to yield gains in both scale and productivity that have offset each other in their consequences for workers [1]. Similarly, a decomposition of wages into unit labor cost and productivity shows domestic privatization bringing about cost reductions and productivity improvements that have offsetting effects on wages [1]. In Hungary and Romania, the scale, cost, and productivity effects of domestic ownership have all been large, while in Russia and Ukraine they have all been small. Foreign privatization has resulted in much larger scale, productivity, and cost effects in all four countries, but the scale effects dominate the productivity effects, which in turn dominate the cost effects. The consequences are the increased employment and wages that are observed after privatization in foreign firms but not in domestic firms.

These cross-country and domestic versus foreign patterns are inconsistent with the simple tradeoff in privatization between efficiency and worker welfare that many observers have assumed. Efficiency-enhancing owners frequently appear to be good for workers, at least in regard to average employment and wage effects. Greater efficiency helps firms expand sales, reducing the likelihood of severe distress and raising labor demand. The evidence suggests that despite workers’ expectations, employment and wages are not systematically reduced by privatization, and in some cases—particularly with foreign ownership—their prospects may actually improve [1].

The main policy implications concern the cost side of a benefit-cost analysis of privatization policies. However, the cost side has received much less attention than the benefit side. The implications of the empirical research discussed here are that some alleged costs of privatization—employment and wage cuts—are likely to be small. The research has much less to say about other potential costs, including the effects of privatization on individual workers or on other types of compensation and work conditions. These are important caveats to bear in mind, but the effects on average employment and wage levels are important questions for policymakers considering privatization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The authors draw heavily on previous work for this article, especially [1], [12]. Version 2 of the article includes an additional “Con,” discusses the differences in the effects of privatization for different types of workers, and reviews new research [7], [8], [9], [13], [14].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© John S. Earle and Solomiya Shpak

Selection bias in privatization research

Source: Brown, J. D., J. S. Earle, and Á. Telegdy. “Employment and wage effects of privatisation: Evidence from Hungary, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine.” Economic Journal 120 (2010): 683–708.

Regression specifications

Source: Brown, J. D., J. S. Earle, and Á. Telegdy. “Employment and wage effects of privatisation: Evidence from Hungary, Romania, Russia, and Ukraine.” Economic Journal 120 (2010): 683–708.