Elevator pitch

Social assistance programs are intended to improve people’s well-being. However, that goal is undermined when eligible people fail to participate. Reasons for non-participation can include inertia, lack of information, stigma, the time and “hassle” associated with applications and program compliance, as well as some programs’ non-entitlement status. Differences in participation across programs, and over time, indicate that take-up rates can respond both positively and negatively to policy change. However, there are clearly very identifiable ways in which relevant agencies can improve take-up.

Key findings

Pros

Although there are many tangible and intangible barriers to participation in some social assistance programs, there are strategies that agencies and organizations can follow to improve access.

Increased access can reduce stigma—potential clients are more likely to take up benefits when they see other people and broader groups of people also taking up benefits. This can have reinforcing effects on participation.

Strategies that simplify program rules can lower agencies’ administrative costs.

Cons

Some strategies for increasing participation, such as outreach campaigns and more convenient operating hours, have direct costs.

Other strategies, such as simplified program rules or less onerous reporting requirements, can undermine program integrity.

Increased assistance program access is costly in and of itself because more benefits will be used.

We lack information regarding how much specific access interventions change people’s behavior, making cost—benefit comparisons difficult.

Author's main message

Many disadvantaged people miss out on financial support by not participating in assistance programs. This can be because of the stigma of receiving benefits, or because of onerous application processes, confusing rules, misinformation, and demeaning delivery methods. Agencies can lower these barriers and boost participation by providing reminder notices, opt-in defaults and automatic enrollment to overcome inertia. They can also conduct outreach campaigns to reduce information gaps and stigma and develop simpler program rules that ease administrative burdens.

Motivation

Social assistance programs take a number of forms, including direct cash transfers, in-kind assistance, service provision, and tax subsidies. But they also share a common principal goal of improving people’s well-being. Many of these programs are offered on a voluntary basis. While this is a feature that may appear accommodating it is also one that requires potential recipients to take active steps to apply for benefits, as well as ongoing steps in order to continue receiving them.

If the programs are means-tested or have other enrollment criteria, applicants and existing beneficiaries may also have to supply additional information in order to establish their eligibility. While the administrative steps associated with enrollment and continuation serve important purposes, they can also act as barriers to participation. Other aspects of social assistance programs, such as the stigma that participation might engender, can also raise barriers.

Such barriers can reduce participation rates among otherwise eligible people. This consequently undercuts the fundamental well-being objectives of assistance programs and reduces their effectiveness. While numerous reasons have been offered for why people might “leave money on the table” by failing to take up benefits, researchers and policymakers are also concerned about other behavioral and unintentional reasons for non-participation.

One set of explanations focuses on simple inertia, or “status quo bias” [1]. Although potential beneficiaries may see the programs as being helpful, they delay taking the active steps necessary for enrollment, simply as a result of inertia or procrastination. Another explanation is that people lack sufficient awareness or information about the programs, their personal eligibility, the benefits of the programs, and the actual application procedures [2]. In addition to these considerations, the time, paperwork burdens, and inconvenience associated with applying for and remaining on public assistance also represent costs that have the effect of lowering participation rates [2]. Other explanations focus on social and psychological factors. For example, receiving public benefits may be considered as stigmatizing or demeaning, which would reduce their value to potential recipients and potentially deter them from applying [3].

Finally, even if people apply for assistance and successfully negotiate every administrative hurdle, they may still not receive benefits if the program runs out of funding. Programs with entitlement status guarantee benefits to all eligible people who apply, but programs without this status may exhaust their funds, which would leave needy and deserving people unserved.

Discussion of pros and cons

Participation rates can and do change

Many disadvantaged people, for a range of reasons, do not participate in social assistance programs for which they are eligible. These reasons can be “strategic,” in the sense of there being a long-term reason associated with deferring benefit receipt or avoiding a program. But they can also be as a direct result of certain features of the program itself, such as onerous application processes, bewildering rules or program choices, misinformation, inconvenient official policies, and demeaning delivery methods. Additionally, burdensome administrative steps associated with enrollment and continued benefit, although serving important programmatic purposes, can also act as barriers to participation.

All of these barriers to participation are addressable by appropriate policy measures, and there has been a considerable amount of empirical research to support these observations.

Participation rates in the US

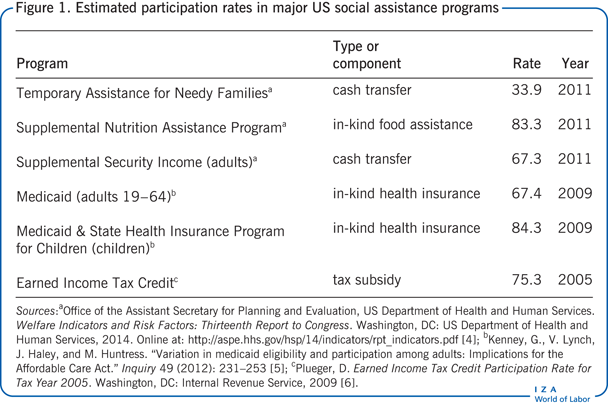

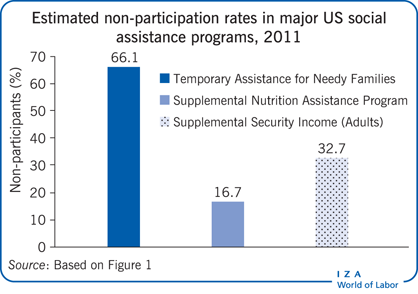

The recent rates of participation in several large US social assistance programs (Figure 1) vary considerably [4], [5], [6]. Approximately just one-third of the lone-parent families that appear to be financially eligible for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which is the largest cash assistance program in the US for disadvantaged families with children, actually participate in the program. An estimated two-thirds of eligible families, or about 3.7 million families, do not participate.

Also, around only two-thirds of the disabled adult households that appear to be financially eligible for the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, which is the largest means-tested cash assistance program for disabled people in the US, actually participate. This leaves about one-third (one million adults) who do not participate. Furthermore, approximately five-sixths of financially eligible households participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which is the largest food assistance program in the US, leaving one-sixth (3.8 million households) who do not participate. Therefore, depending on the program, somewhere between one-sixth and two-thirds of those who appear to be eligible—which amounts to many millions of Americans—fail to take up benefits.

In addition, a June 2000 survey of households that were eligible for, but not participating in, the SNAP in the US found that just over one-half incorrectly thought that they were ineligible, which reinforces the “information” explanation discussed previously. One-third of households indicated that they would not apply even if they were eligible. Virtually all of the households cited SNAP as being not consistent with personal independence and many cited administrative “hassles.”

The survey also found that many households had initiated but not completed applications. For some of these households, eligibility-related circumstances had changed, but for many others, administrative hassles and inconvenience were significant influencing factors [7].

A 2011 survey of low-income tax-filing households who failed to claim the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) similarly found a general lack of program awareness and widespread misperceptions about benefits and eligibility [8]. The research further indicates that some reasons for non-participation are more salient for some programs and for some segments of the population than for others.

Participation rates in the UK

Participation in social assistance, or “take-up,” is also an issue in other countries, including the UK.

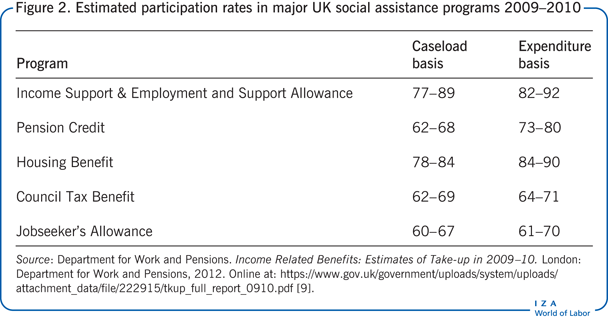

The UK regularly reports participation rates in its major cash-transfer programs on both caseload and an expenditure basis [9]. The caseload rate indicates the percentage of eligible people who are estimated to participate, while the expenditure rate indicates the percentage of eligible benefits that are estimated to be claimed. Estimated take-up rates for the Income Support program and Employment and Support Allowance program, which mostly benefit low-income working-age people, are relatively high, as are take-up rates for the Housing Benefit subsidies. However, take-up rates for Pension Credit, which mainly assists disadvantaged elderly people, and for the Council Tax Benefit and Jobseeker’s Allowance programs, are substantially lower (see Figure 2).

The UK estimates also show another common characteristic of take-up. People who are eligible for higher benefits are more likely to participate than people who are eligible for lower benefits. This generally results in take-up rates that are calculated on the basis of expenditures being higher than rates calculated on the basis of caseload counts. Estimates from other OECD countries also show variation in take-up rates, as well as non-universal participation.

Social scientists have offered numerous reasons for why people might “leave money on the table” by failing to take up benefits. Some of the behavior may be strategic or purposeful, such as when potential TANF recipients avoid participation to “bank” benefits against the program’s lifetime limits, or when TANF administrators actively divert clients from the program [10], [11].

Policies can make a difference

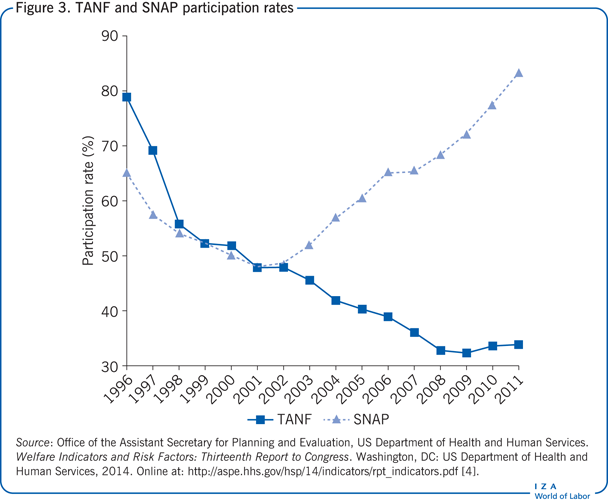

The TANF and SNAP programs in the US offer strikingly contrasting examples (see Figure 3). In 1996, participation in the TANF program among financially and categorically eligible households stood at 78.9%, while participation in the SNAP (which at that time offered less convenient and more stigmatizing food coupons) stood at 65.1%. Following legislation in 1996 that placed numerous restrictions on both programs, participation rates for TANF and the SNAP fell, reaching identical 48% rates by 2001. Thereafter, the trends diverged.

Participation in the TANF program continued to fall until 2009. Since then it has been mired around one-third, while participation in the SNAP generally increased, reaching 83.3% in 2011. A continuation of restrictive policies in TANF following the reforms in the mid-1990s, and the adoption of additional restrictive policies in 2005, in all probability contributed to the fall in that program’s participation rate. The adoption of numerous accommodating policies in the SNAP program also probably contributed to the rise in that program’s participation rate.

Participation rates in the UK programs have also changed over time. Take-up in the Income Support and the Employment and Support Allowance and Housing Benefit programs has been trending down in recent years. Take-up in Pension Credit has been trending up, and take-up in Council Tax Benefit and Jobseeker’s Allowance programs has remained stable (following earlier periods of decline) [9].

Observational and experimental studies show how specific interventions and policies can affect take-up. For example, a careful analysis based on surveys of SNAP office procedures and potential clients’ behavior found that outreach efforts increased people’s awareness of eligibility. The same analysis found that lower administrative burdens, in the form of more convenient office hours and child-friendly offices, and less demeaning practices in the form of positive office supervisor attitudes and not finger-printing clients, increased the likelihood of people completing applications [7].

A recent experiment to encourage EITC take-up in the US is also interesting and relevant. Each year the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) sends automated reminder notices to low-income tax-filers who appear to qualify for the EITC but fail to claim the credit. Over the period 2006−2009, the response to these modest “nudges” to overcome inertia was estimated to be between 41% and 52% [8].

A 2009 experiment sent additional reminder notices to households that had not responded to the first set and randomly varied the notices’ information content, complexity, and positive messaging. Simply providing a second follow-up notice resulted in an additional 14% of households applying for the EITC. Notices with better information about potential benefits boosted the filing rate even higher, as did notices with simpler designs. However, notices with “stigma-reducing” messaging were no more effective than ordinary notices, perhaps due to the generally positive impressions of the EITC [8].

In sum, the automated notice experiment demonstrated how interventions to address inertia, information gaps, and paperwork burdens could increase participation.

The effect of stigma

A natural experiment involving the US School Breakfast Program reveals how program provision can be changed in order to reduce stigma. Unlike free and reduced-price school lunches, which are eaten at a time when all school students are generally in a cafeteria, free and reduced-price school breakfasts are usually only offered before school starts. They are also often eaten only with other eligible children. Taking a breakfast in this setting marks out a student, in all probability, as coming from a poor family, which effectively stigmatizes the meal.

Researchers examined changes in school breakfast participation when the meals were made available free of charge, universally to all students in selected low-income schools, rather than being provided free only to eligible children. As might be expected, participation increased for the children who were newly provided with free breakfasts, but participation also increased for the children who had been eligible for free breakfasts all along. Having a mix of children in the cafeteria, rather than only the disadvantaged children, appeared to reduce the stigma of these meals and increase participation [12].

Costs of compliance

Simplifying the rules and streamlining eligibility for programs not only reduces compliance costs for potential participants but can also reduce compliance costs for administrators. Fewer, simpler rules generally mean that there are fewer issues to check and to track. They can also lead to shorter applications that are quicker to process. Automatic eligibility determination and monitoring through linked administrative systems provide similar benefits. These processes effectively reduce the information that has to be entered by clients or caseworkers and allow for faster processing. Administrative savings from simplification, streamlining, and automation can be used to offset some of the costs of increased participation.

Combined applications

When people are potentially eligible for multiple programs, participation can be increased by combined application procedures and by one-stop centers and processes. As the description suggests, combined applications allow people to apply for multiple programs with a single form.

For example, several US states allow people who apply for means-tested disability support to use the same applications to qualify for SNAP. One-stop centers take this idea further and allow people to apply for all of the programs for which they might be eligible at a central office and in a single appointment, rather than making them attend multiple agencies or sit through multiple appointments.

One-stop functions can similarly be performed by skilled caseworkers who take comprehensive assessments of people’s needs when they initially seek help and then direct them to all of the services and benefits for which they are eligible. The Victoria Department of Human Services in Australia is currently testing this type of caseworker approach.

Downsides of improving program access

Greater program access does have its downsides. The most significant of these is the cost associated with the increased use of benefits and services. Bureaucratic and other barriers to program participation act as rationing devices, even if they are capricious and unfair. A related concern is the cost of the administrative efforts to improve access. Outreach campaigns, expanded office hours, child-friendly facilities, caseworker training, and reminder notices all have direct costs.

An additional concern involves the underlying rationale for program rules and policies. Social assistance programs are not generally available to all-comers, but instead are restricted to specific groups of people. For example, means-tested benefits are intended only for low-income people and are often reduced as people’s incomes or resources increase. Some programs have category-based eligibility rules in which benefits are restricted to certain population groups such as children, or specific circumstances such as pregnancy, disability, or unemployment.

In general, any social assistance program with eligibility criteria will require policies and processes to check those criteria. In designing those policies and processes, administrators must ensure to balance concerns between inhibited program access, if the procedures are too onerous, and reduced program integrity, if the procedures are too lenient.

Limitations and gaps

There are several gaps in the current understanding of program take-up, the most significant being that the full extent of the problem is not yet known. Calculations of take-up rates are formed by dividing the number of program participants by the number of eligible households, or people. In most cases, accurate numbers of participants can be obtained from a program’s administrative records.

However, information on the number of eligible people usually has to be drawn from other sources, such as large-scale surveys. The measures in those sources tend to be cruder, less complete, and less accurate than the measures in administrative systems. For example, in order to estimate the number of people in the US who are eligible for SNAP, analysts require monthly information regarding household composition, the sources and amounts of income, financial and vehicle assets, and participation in other means-tested programs. Data sources seldom have all of these measures, or have them at the right frequencies. More precise estimates of eligibility would also require measures of characteristics such as origin, drug histories, and felony histories, which can all limit eligibility. These characteristics are even less likely to be recorded in surveys. Few countries, other than the US and UK, systematically and regularly report take-up rates.

Another gap is that while evidence of participation barriers has been found for many programs, it is difficult to determine exactly which barriers are in place and how high the barriers are. Research to date points to the existence of barriers, but not their precise magnitudes or extent. In relation to this, we also lack estimates of the responsiveness of program participation to changes in the barriers. These estimates are necessary in order to rationally evaluate the trade-offs inherent in program rules.

Summary and policy advice

A substantial number—and in some cases the majority—of potentially eligible participants fail to take up benefits in social assistance programs. There are rational reasons why some people may elect not to participate, e.g., as a result of inertia, information problems, administrative hassles, stigma, and funding limitations, etc.

However, the precise role and extent of these reasons in specific programs and for particular populations are less well understood. To a certain degree, social scientists and administrators are sympathetic to these barriers. However, at another level, they are somewhat less attentive, as some barriers lack a clear price tag and others lack quantifiable benefits. A further problem is that administrative expenses, whether necessary or not, are all too often viewed as wasteful in and of themselves.

Further research is required and better data on program access are seriously needed. For this particular issue, research serves a dual purpose, by not only identifying the obstacles to access, but also by increasing awareness of programs and take-up, and by lowering information barriers.

Nevertheless, policymakers should in the meantime be more mindful of potential barriers. Although precise estimates of people’s sensitivity to some barriers is currently lacking, informed guesses can be made regarding potential burdens—for example, by approximating the paperwork burden of an entry on a form and comparing it to the rough benefits it might produce. Instead of a “better safe than sorry” approach to adding program rules, more neutral criteria could be applied that would treat the uncertainties associated with additional complexity in the same way that uncertainties associated with simplification would be treated.

Observational and experimental studies show how specific interventions and policies can affect take-up. Research demonstrates that lower administrative burdens, in the form of more convenient office hours and child-friendly offices, and less demeaning practices, in the form of positive office supervisor attitudes and not finger-printing clients, increased the likelihood of people completing applications [7].

Agencies can also lower barriers and boost participation by providing reminder notices, opt-in defaults, and automatic enrollment to overcome inertia. They can also conduct outreach campaigns to reduce information gaps and stigma and develop simpler program rules that ease administrative burdens.

Any social assistance program with eligibility criteria will require policies and processes to check those criteria. In designing those policies and processes, administrators must balance concerns between inhibited program access (if the procedures are too onerous) and reduced program integrity (if the procedures are too lenient).

In addition, simplifying the rules and streamlining eligibility for programs not only reduces compliance costs for potential participants but can also reduce compliance costs for administrators. Automatic eligibility determination and monitoring through linked administrative systems provide similar benefits. These processes effectively reduce the information that has to be entered by clients or caseworkers and allow for faster processing. Administrative savings from simplification, streamlining, and automation can be used to offset some of the costs of increased participation.

More generally, policymakers and the general public not only need to develop a rational tolerance of administrative expenditures but also need to develop a tolerance of small, but reasonable, levels of improper and unwarranted social assistance benefits.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© David Ribar