Elevator pitch

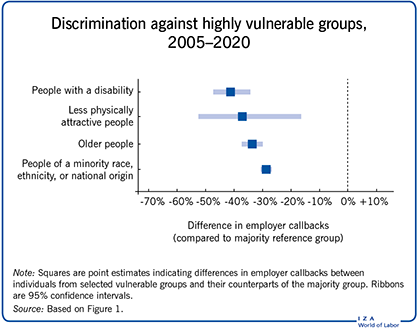

Over the past decades, academics worldwide have conducted experiments with fictitious job applications to measure discrimination in hiring. This discrimination leads to underutilization of labor market potential and higher unemployment rates for individuals from vulnerable groups. Collectively, the insights from the published research suggest that three groups face more discrimination than ethnic minorities: people with disabilities, less physically attractive people, and older people. The discrimination found in Western economies generally persists across countries and is stable over time, although some variation exists.

Key findings

Pros

Hiring discrimination based on gender appears mainly in occupations dominated by a specific gender.

Age discrimination is considerably lower in the US than in Europe.

Compared to other forms of discrimination, the high beauty premium in hiring stands out.

The level of ethnic discrimination varies by origin and is highest for Middle Eastern and Northern African candidates but lowest for European minorities.

Research increasingly focuses on identifying the mechanisms that may explain discrimination, but no conclusive view has emerged.

Cons

The past decades have seen little reduction in hiring discrimination.

Age discrimination in hiring is substantial and under-researched in many countries.

People with a disability are discriminated against most, although it is uncertain to what extent the hiring discrimination is productivity-related.

Candidates open about their sexual orientation receive significantly fewer positive responses to their job applications.

Ethnic hiring discrimination varies geographically, being highest in European countries such as France and Sweden and lowest in Germany.

Author's main message

The global research findings on hiring discrimination against vulnerable groups are inconsistent with policies (e.g., hiring quotas or subsidies) that focus exclusively on one vulnerable group or another. Broad diversity policies are needed instead. Policymaking should prioritize helping the most disadvantaged minorities, paying particular attention to intersectional hiring discrimination based on multiple personal characteristics. Moreover, policymaking should support research that (i) evaluates under-researched types of discrimination, (ii) provides broader insights into discrimination mechanisms, and (iii) pilot tests the efficacy of policy interventions.

Motivation

Policymakers have several incentives to combat hiring discrimination. First, hiring discrimination is unethical and undesirable. It contradicts the principle of equal treatment and ability-based allocation of work opportunities. Discrimination perpetuates existing inequalities that disadvantage underrepresented and vulnerable social groups.

Second, hiring discrimination harms individual employees and employers. Prospective employees experience reduced job opportunities, decreased income, and hampered well-being. Employers face increased labor costs and operational inefficiencies when denying qualified candidates a job. Still, they pursue discrimination because of personal preferences or (inaccurate) beliefs about productivity differences between groups.

Third, the underutilization and misallocation of talent due to hiring discrimination hinder economic growth. Discrimination contributes to higher unemployment of minorities, increasing reliance on social welfare programs. Because discrimination based on various personal characteristics (e.g., ethnicity, age, or gender) is forbidden in many countries, legislators prohibit it, impose sanctions against employers who perpetrate it, and mandate diversity actions to counter it.

Knowing when, where, and against which groups hiring discrimination occurs is indispensable for targeting policy interventions. Following a recent wave of empirical research examining hiring discrimination through field experiments, overview studies have synthesized this stream of work and identified general patterns and trends. Here, these findings are summarized. This article also lists the limitations of the current field experimental work and discusses policy recommendations.

Discussion of pros and cons

Severity of hiring discrimination across vulnerable Groups

The correspondence experiment is considered the gold standard for testing hiring discrimination in the labor market. In such experiments, researchers send fictitious job applications to actual job vacancies. Personal characteristics like ethnicity, gender, or age are randomly assigned across resumes of groups of fictitious job candidates, revealing minority or majority group membership. By keeping other individual characteristics of the fictitious job candidates constant, experimenters can causally appraise the impact of the randomly assigned characteristics on callbacks from employers. More specifically, the experimental data enable estimating hiring discrimination by comparing positive callbacks (i.e., the number of positive responses or interview invitations) between groups of fictitious job candidates.

In recent decades, many studies have used the correspondence experiment method to estimate hiring discrimination, testing numerous personal characteristics or so-called discrimination grounds. For example, to measure hiring discrimination based on ethnicity, researchers typically vary candidate names between fictitious applications to signal different ethnic identities. Conversely, age is usually indicated by birth date or work experience. In what follows, it is detailed what is known thus far about hiring discrimination through the lens of correspondence experiments conducted worldwide, summarized in meta-studies.

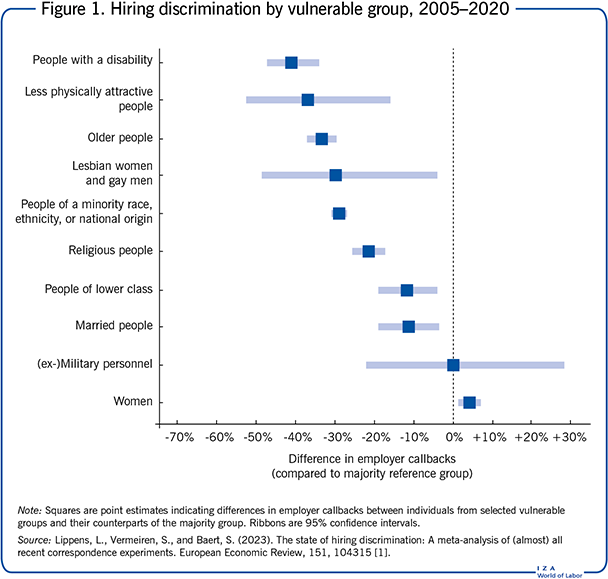

Hiring discrimination based on race or ethnicity is the most studied type [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Figure 1 shows average callback differences from a meta-study of recent correspondence tests [1]. These differences, expressed in percentages, indicate how much less (or more) frequently job candidates of a minority group receive positive responses than candidates of a corresponding majority group. These positive responses typically include an invitation to an interview or a request for additional information about their application. Candidates of a different race, ethnic identity, or national origin than the majority get 29% fewer positive callbacks, on average, from employers (see Figure 1). However, to some extent, this moderate average penalty hides variation in the level of discrimination across subgroups [1]. For example, discrimination is highest for applicants of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) descent, who receive 41% fewer positive callbacks than their majority counterparts in correspondence tests worldwide, on average. Conversely, Northern and Western European applicants face just about 19% fewer positive callbacks (mostly in European experiments), on average, and hiring discrimination against Hispanics is almost non-existent (mainly in US experiments).

Although race and ethnic discrimination are the most common discrimination grounds in the correspondence experiment literature, discrimination based on disability, physical unattractiveness, or older age seems at least as problematic; each of these types of discrimination amounts to a higher hiring penalty. To date, relatively few field experiments have tested disability as a ground for discrimination in hiring, while this form seems most penalized in hiring [1]. Candidates with disabilities face an average hiring penalty of 41% compared to those without disabilities (see Figure 1). On the one hand, experiments on physical disability include blindness, deafness, or being a wheelchair user. On the other hand, experiments on mental disability comprise psychodiagnoses such as autism spectrum disorder or past depression. Both forms of disability are usually indicated in the cover letter accompanying the fictitious candidates’ resumes. People with a physical disability receive 46% fewer positive callbacks, while persons with a mental disability face 38% fewer positive callbacks, on average [1].

In correspondence experiments, researchers have consistently considered disadvantages in skills or competencies when submitting fictitious applications differing randomly in disability status. This approach guaranteed that they could interpret differences in responses as discriminatory. In other words, when testing discrimination, experimenters tried to ensure that differences between candidates were strictly unrelated to job performance. However, suppose employers withhold job-related information from the vacancies that is crucial for the researchers to assess whether the assigned disability could be work-limiting. In that case, researchers might send fictitious applications in response to jobs for which the candidates with disabilities are effectively less suitable or even unqualified. Consequently, differential treatment by some employers could be legitimate, resulting in overestimating the severity of disability discrimination.

The beauty premium is also visible in hiring, given the substantial discrimination based on physical unattractiveness [1]. More attractive people receive, on average, 56% more positive callbacks (or, put differently, less attractive people receive 37% fewer positive callbacks; see Figure 1). Fieldwork with fictitious resumes exhibiting differences in physical attractiveness consists primarily of experimental manipulations of photographs eliciting subjective differences in facial attractiveness. Alternative signals include facial disfigurement or body art (e.g., tattoos).

In the fieldwork on age discrimination in hiring, researchers compare responses to applications of older candidates with those of younger candidates. Typically, older candidates are around 50 years old, and younger applicants are around 30 [1], [10]. However, age gaps in recent experiments are as narrow as six years and as broad as 35 years. On average, older applicants receive about 34% fewer positive callbacks than their younger counterparts (see Figure 1). Measured age discrimination generally intensifies as the age gap grows [10]. Age discrimination in hiring also seems to depend on career patterns: irrelevant out-of-field work experience alongside older age has a particularly negative impact on the chance of an employer callback [11]. In other words, when older candidates have equally relevant work experience as their younger counterparts but more irrelevant experience, they face considerable age discrimination.

Women and men open about their sexual orientation receive 30% fewer positive responses to their applications, on average, although this figure varies substantially between correspondence studies (see Figure 1) [1]. This personal characteristic is usually signalled through membership in an organization supportive of the LGB (i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual) community [1], [12]. Sexual orientation is rarely indicated by explicitly mentioning the gender of the partner or the orientation itself. Similar to the reservations about experiments considering disability, it is unclear whether the hiring penalty based on sexual orientation is genuinely discriminatory. Because of the way sexual orientation is signalled, differences in callbacks can occur due to discriminatory attitudes regarding LGB orientation, which would constitute discrimination, but also due to a negative stance against activism signalled through an affiliation with an organization that supports LGB rights [12]. Notably, sexual orientation discrimination is more pronounced for low-skilled jobs, especially among men [12].

Gender discrimination in hiring, which is also widely evaluated, appears generally absent in correspondence experiments, with a slight overall preference of employers for female candidates [1]. However, while many studies find no gender effect, some correspondence tests find evidence of discrimination against women, and others find that men are disadvantaged [13], [14]. More specifically, male candidates are typically favored over female candidates in experiments involving (mixed and) male-dominated occupations (such as a carpenter or truck driver). In contrast, female candidates are usually favored in female-dominated occupations (such as an HR professional or a nurse). These findings also have implications for gender earnings differences as male-dominated (female-dominated) occupations are relatively better (worse) paying, sustaining the gender pay gap [13].

Other (less researched) grounds for discrimination are religion, wealth, civil status, parenthood and fertility, criminal record, and military, political, and union affiliation. Most fieldwork on religious discrimination in hiring has focused on Muslims, who receive, on average, 23% fewer positive responses compared to their non- or majority-religious counterparts. Nevertheless, it is difficult to clearly distinguish between religion and ethnic identity, as both are often signalled through names in correspondence tests, sometimes with an added religious element such as volunteer work for a religious organization. Because meta-research is still limited concerning the remaining grounds, conclusive statements about the severity of the associated discrimination cannot be made. People of lower class and married people most probably face a limited hiring penalty, while (ex-)military personnel experience no discrimination (see Figure 1) [1].

Region and country differences in hiring discrimination

Several differences in hiring discrimination exist between regions and countries. Concerning ethnicity, within Europe, hiring discrimination appears highest in Ireland, Czechia, Finland, Sweden, France, and Italy and lowest in the Netherlands and Germany [1]. Studies in Finland, Sweden, France, and Italy show significantly higher levels of discrimination than in the US, while ethnic hiring discrimination is markedly lower in Germany than in the US [1], [5]. One reason for the lower discrimination levels in Germany is that employers use more extensive application procedures [5], [9]. Employers sometimes rely on assumptions—either accurate or inaccurate—about group-level productivity to infer the productivity of the individual (e.g., ethnic minority candidates presumably having lower language skills, making them less productive) [15]. Thorough selection procedures help counter reliance on false assumptions by diverting employers’ attention to relevant individual characteristics that matter for personnel selection.

Next, examining the averages of specific ethnic minority groups, meta-studies reveal that Black minority groups are discriminated against more in certain European countries compared to the US, notably in France, Great Britain, and Belgium [5], [8]. European Black job candidates might be perceived as more ‘culturally foreign’ than their US counterparts, for example, because of country differences in migration, historical treatment, and representation [5]. In addition, minorities of Middle Eastern and North African origin are worse off in France than in Germany or the Netherlands. More generally, country differences might be driven by institutional disparities, such as (the lack of) legal action at the national level [5]. Also, macroeconomic conditions such as increased demand for personnel when relatively few people seek work (i.e., a tight labor market) can shape disparities in hiring discrimination between different countries. For other ethnic groups, few differences can be found in discrimination between regions or countries because they either do not exist or because too few experiments have been conducted to draw statistically convincing conclusions.

A breakdown by region further reveals that hiring discrimination based on age differs significantly between Europe and the US [1]. In European correspondence tests, older applicants receive about half fewer positive responses than younger applicants. This penalty is much lower in the US, with about a third fewer positive responses, even though the ages and age differences in the American tests were much higher than in the European experiments. Within Europe, age discrimination appears lower in Belgium than in the UK, France, or Spain.

Regarding gender, the occupational disparities favoring women in female-dominated occupations and men in male-dominated occupations (i.e., the gender gradient), as mentioned already above, are consistent across countries [13], [14]. Country-level factors such as gender inequality, education level, economic prosperity, or human development do not seem related to levels of gender discrimination in hiring [14]. This geographical consistency suggests that the gender gradient is a global phenomenon. However, most correspondence tests are performed in so-called WEIRD (i.e. Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) nations, primarily in Northern America and Europe. Thus, caution should be exercised about extrapolating this cross-country stability regarding gender discrimination in hiring to other parts of the world.

Evolution of hiring discrimination over time

Hiring discrimination is relatively stable over time [1], [3], [4], [7]. Although reliable statements can only be made about race, ethnicity, national origin, gender, religion, disability, age, and sexual orientation, both at the regional and the country level, hiring discrimination has shown little movement in the past few decades. This finding is remarkable given the diversity-promoting efforts of many firms, the anti-discrimination legislation in many countries, and the equity-enhancing policy plans at the (supra)national level, including the European institutions’ recent European Pillar of Social Rights. The latter puts equal opportunities and access to the labor market front and center.

Yet, two temporal trends appear. First, ethnic discrimination in European correspondence experiments seemed to have decreased between 2005 and 2020 [1]. Nevertheless, this trend can be explained entirely by the research focus of the past decades. In the 2015–2020 period, applicants of European and West Asian (i.e., mainly Turkish) origin received proportionately more attention, and applicants of Middle Eastern and North African origin received less attention in hiring discrimination research than in the 2005–2014 period. At the same time, it is known that the latter group is more strongly disadvantaged in the hiring process. Thus, the now weakened post-millennium research focus on Middle Easterners and Northern Africans most likely led to this apparent regional decrease in hiring discrimination.

Second, gender discrimination in hiring appears to have reversed globally [14]. Whereas female applicants faced hiring penalties compared to male candidates before 2009, this overall penalty disappeared and slightly turned in favor of females in recent years. In contrast to the seeming decrease in ethnic hiring discrimination in Europe, changes in study design (or period or location) did not impact the shift in gender discrimination. As mentioned earlier, gender domination in occupations plays a crucial role in hiring discrimination based on gender, with women (men) facing hiring penalties in male- (female-)dominated occupations. However, from 2009 onwards, employers prefer female candidates for female-dominated and gender-balanced jobs. Women also no longer face significant discrimination in male-dominated professions.

Some meta-studies indicate (weak) evidence for temporal changes in hiring discrimination for specific ethnic groups and certain countries. First, discrimination against Latinos in the US seems to have declined slightly between 1990 and 2015 [7]. Second, ethnic discrimination in hiring against Blacks, Middle Eastern, and North Africans has decreased in France since 2005, whereas it has increased in the Netherlands since 1985 [4]. France stands out as the only country where an evident decline in hiring discrimination is observed, but the downward trend started from a very high baseline level of discrimination and remained high relative to other Western nations. Third, hiring discrimination against minorities of Middle Eastern and North African origin seems to have risen across countries since the millennium. This upward trend is presumably due to the increased (negative) attention on this subgroup following the political response to terrorist attacks in WEIRD countries during the early 2000s [4].

Limitations and gaps

Context differences and mechanism ambiguity

There are a few limitations to the current hiring discrimination literature. First, differences in context across fieldwork sometimes make formally comparing findings difficult. For example, how comparable is age discrimination against 50-year-old applicants in the US in 2003 and Belgium in 2015? It is possible to control for observed differences between studies, such as location or period, but usually it is not possible to account for unobserved differences, such as employer attitudes and personalities. A comparison across contexts also requires considering macroeconomic labor market factors. In this respect, some research indicates that competition between employers for shortage occupations diminishes hiring discrimination. Nevertheless, comparisons will always be restricted by what researchers can observe when overviewing multiple independent studies.

Second, correspondence experiments, which comprise a large part of the experimental fieldwork, have suffered from a lack of innovation in the past decades, leaving the correlates and mechanisms of discrimination under-researched [2], [5], [9], [15]. For instance, it is unclear what exactly drives the regional differences between various European countries and the US regarding age discrimination in hiring [1]. European countries often enforce retirement ages and more robust job security protection, which could lead employers to prefer more flexible, younger hires with better prospects and who are usually less costly. In the US, retirement timing is more individualized, age-based expectations are less rigid, and hiring older employees carries less risk because severance is typically less costly. Still, age discrimination can persist due to productivity concerns. These regional specificities could have resulted in differences in hiring discrimination based on age.

To some extent, the innovation gap has been filled by vignette experiments. In these experiments, recruiters assess fictitious resumes with varied candidate characteristics in a controlled setting. The designs typically isolate the influence of these characteristics on employer perceptions, aiming to reveal underlying stereotypes and discrimination mechanisms. Age discrimination, for example, could be motivated by the stigma around lower educational attainment, flexibility, and being current with technology. Conversely, discrimination against transgender people might be due to feared future health problems, such as mental health issues or medical complications associated with gender-affirming treatments. However, these studies are limited to elements that can be randomized, which evidently exclude factors such as national labor policies. In addition, they are prone to social desirability bias and do not fully capture the complexity of real-world discrimination.

Gaps in empirical work on hiring discrimination

Current research has a few notable gaps. Field experiments on hiring discrimination have generally been conducted in so-called WEIRD countries with little focus on Africa, Asia, or Southern America [1], [13]. Specifically, some discrimination grounds, like political affiliation, are underexamined. For others, like age, there is limited knowledge about time or location heterogeneity because, to date, research has focused on restricted periods or few countries; the relatively few studies on age discrimination are restricted to a handful of European countries and the US [1], [10].

Moreover, most of the hiring discrimination literature examines callback differences in online advertised entry-level positions [2], [4]. This focus negates a significant part of hiring discrimination formed through barriers in professional networking, to which vulnerable groups often have limited access, leading to reduced informal opportunities. In addition, because less is known about hiring discrimination in more senior positions, the estimates of hiring discrimination are less externally valid for jobs requiring substantial experience or seniority.

Discrimination research using correspondence tests also largely ignores later stages in the hiring process or other labor market outcomes. For instance, ethnic discrimination after the first callback is only weakly correlated with discrimination in the resume screening stage [6]. It appears to almost triple when applicants have reached the job interview stage. Also, correspondence experiments do not provide information about workplace, training, promotion, or layoff discrimination. Thus far, direct causal estimates for these outcomes are lacking.

Finally, researchers can extend efforts to mapping the consequences of hiring discrimination and finding solutions [1], [5], [13], [15]. For example, how does discrimination influence the job-seeking behavior of vulnerable individuals and their propensity to drop out of the labor market? Or how does a dynamic labor market with healthy competition between employers affect hiring discrimination based on different personal characteristics? While current meta-studies of hiring discrimination experiments provide substantial knowledge about against which groups employers discriminate, the above questions remain partly unanswered.

Summary and policy advice

Relying on evidence from various meta-studies, the widespread and lasting nature of hiring discrimination cannot be denied. Discrimination across Western economies disadvantages many vulnerable groups and appears constant over time. Discrimination is most severe against people with a disability, lower physical attractiveness, or older people, followed by people of different races, ethnic identities, or origins and lesbian women or gay men. However, subgroup differences exist, with some groups, like people of Middle Eastern or Northern African origin, facing higher-than-average hiring penalties.

Anti-discrimination and diversity-promoting measures, such as hiring quotas, hiring subsidies, or diversity awareness interventions, should focus not only on well-documented grounds, such as ethnicity and gender, but also on less-documented but more significant grounds for discrimination, including disability or age. In other words, policies to increase diversity in the labor market should also be given a diverse interpretation. At the very least, policymakers should target the minority groups that are most disadvantaged in the selection process. This approach also entails paying attention to those vulnerable groups that face multiple disadvantages.

Furthermore, policymakers should support research that uncovers discrimination mechanisms and pilots targeted interventions against hiring discrimination. Merely monitoring and measuring discrimination is insufficient. Research into the mechanisms of hiring discrimination is essential to know when and why it occurs. Subsequently, this research can inform about the types of intervention that can be useful in combatting discrimination, which researchers can then test.

Finally, policymakers should not wait to act against hiring discrimination. Three main strategies based on current evidence are proposed. First, policymaking should put more effort into enforcing anti-discrimination legislation [15]. Making discrimination more costly, for example, through financial sanctions, effectively reduces discrimination driven by taste or personal preference. Second, policymaking should promote standardized application procedures [5], [9], [15]. Such procedures can (i) decrease the dependence on easily observable characteristics like gender or age that signal information about group productivity and (ii) increase the reliance on individual, predictive signs of work performance. Third, policymaking should raise awareness of discrimination in hiring [9], [13]. This strategy primarily involves acknowledging and echoing what is already known about hiring discrimination against vulnerable groups, as is done here.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous referee(s) and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the authors (together with Abel Ghekiere, Pieter-Paul Verhaeghe, Eva Derous, and Siel Vermeiren) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [1], [15]. Financial support from Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) under grant number 12AM824N is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The authors declare to have observed these principles.

© Louis Lippens, Brecht Neyt, and Stijn Baert

Correspondence testing methods and meta-studies

Correspondence testing method: In the social sciences, the correspondence testing method is considered the gold experimental standard for measuring hiring discrimination. In these experiments, personal characteristics like gender or age are randomly assigned to resumes of fictitious applicants, which are subsequently sent to real vacancies. Experimenters can then causally interpret differences in responses from recruiters or employers in terms of discrimination.Meta-studies: Meta-studies systematically summarize findings from multiple independent studies that address comparable research questions. They synthesize the respective body of literature and attempt to derive more comprehensive conclusions than individual studies. By aggregating findings, meta-studies help identify patterns, trends, or discrepancies across similarly designed studies.