Elevator pitch

A wide range of high involvement management practices, such as self-managed teams, incentive pay schemes, and employer-provided training have been shown to boost firms’ productivity and financial performance. However, less is known about whether these practices, which give employees more discretion and autonomy, also benefit employees. Recent empirical research that aims to account for employee self-selection into firms that apply these practices finds generally positive effects on employee health and other important aspects of well-being at work. However, the effects can differ in different institutional settings.

Key findings

Pros

High involvement management is associated with higher productivity and better economic performance of firms.

High involvement management gives more discretion to employees, and high job control weakens the negative link between job demands and employee well-being.

Greater autonomy at work leads to greater employee well-being.

Multiple theoretical frameworks link high involvement management to employee well-being and health outcomes.

Innovative work practices should lead to working smarter, not necessarily harder.

Cons

High involvement management can lead to higher work intensity.

Increasing the intensity of work may erode employee well-being and harm performance.

High involvement management might increase strain and lead to higher risks of occupational accidents and sickness-related absenteeism.

Whether it is profitable for firms to redesign jobs for workers’ benefit varies with firm characteristics and market conditions.

There is no agreement on which sets of high involvement management practices are sufficient to transform the working environment.

Author's main message

While empirical studies have linked high involvement management jobs with firm productivity and employee well-being and health, only recently have studies accounted for the possibility that more able employees are more likely to enter such jobs. If unaccounted for, this employee self-selection will exaggerate the benefits of high involvement management for employees. However, even after self-selection is taken into account, the employee effects are generally positive, suggesting that firms may want to invest in these practices, which seem to improve both firm outcomes and employee well-being, at least in some institutional settings.

Motivation

Change is a constant facet of modern working life. In many cases, change is introduced by management and is related to the way work is organized. Innovative work practices have become increasingly popular in contemporary human resource management in both industrialized and developing countries. Examples include:

self-managed work teams;

problem-solving groups;

management information-sharing with employees;

incentive pay;

and such supportive practices as:

employer-provided training; and

associated recruitment methods.

Such techniques were first articulated and advocated by management thinkers in the early 1980s, though many individual practices, such as incentive pay, have been around for hundreds of years.

These management innovations generally aim to increase flexibility in the workplace, improve labor-management cooperation, boost employee involvement in decision-making, and expand employees’ financial participation in the firm. Individually, these innovative work practices do not typically signal the coherent presence of high involvement management; rather, the consensus is that bundles of such practices are needed to transform the working environment. There is still no agreement, however, about which sets of practices are sufficient or whether there is a universally applicable set of practices that would work in all cases.

Discussion of pros and cons

The theory of high involvement management

High involvement management has significant impacts on firm and employee outcomes. An extensive empirical literature examines the relationships between high involvement management and firms’ long-term economic performance, including productivity and profitability [1].

While the predominant view in the economic literature is that firms adopt such management practices to achieve these gains, it is less clear whether these practices also benefit employees directly. Much less is known about the effects of high involvement management on employees’ health and other important dimensions of well-being at work than about the effects on firms. But the impacts on employees are potentially very important, because employee well-being is associated with fewer sickness-related absences and higher productivity. Thus, if high involvement management has negative effects on employee well-being (e.g. increased stress and psychological pressure due to more responsibility), the direct positive effects on firm productivity may be eroded, at least to some degree.

Multiple theoretical frameworks link high involvement management to employee well-being and positive health outcomes. A demand–control model suggests that jobs with high demands but low control tend to lead to stress at work [2].

Two starkly contrasting views have been proposed in the theoretical literature. One view argues that high involvement management makes work more rewarding, meaningful, and challenging by increasing employees’ discretion and autonomy at work. This notion predicts that employee well-being should increase as a result of the introduction of high involvement management practices. In particular, the demand–control model contends that greater discretion at work should eventually lead to lower levels of occupational stress. This theoretical view does not directly address the impact of high involvement management on employees’ workloads, but innovative work practices should lead to working smarter, not necessarily harder.

The second view takes a more critical stance on the effects of high involvement management on workers’ well-being. This strand of the literature claims that high involvement management increases the workload and the pace of work while only marginally increasing the control possibilities of individual employees. In this view, employees may gain some discretionary decision-making, but they may also lose control, especially over the pace of their daily work. The increased pace of work, in turn, diminishes overall well-being at work and increases the prevalence of sickness, absenteeism, and occupational accidents. It is also possible that not all workers want additional discretion, since discretion entails responsibility, which some workers might not welcome.

According to the demand–control model, increased demands at work that are not accompanied by increased discretion or rewards for workers should reduce employee well-being. Additionally, if high involvement management practices, such as self-managed teams, substitute peer control for supervisor control, employees’ stress could increase rather than diminish. In this view, high involvement management reduces employee well-being by intensifying work and increasing the perceived level of stress.

Thus, because the theoretical impact of high involvement management on employee well-being is ambiguous, the issue is essentially an empirical one that has to be solved using appropriate data and methods.

Empirical evidence on high involvement management

The empirical literature on the relationship between job control and job demands and subjective well-being at work tends to support the most important predictions of the demand–control theoretical framework. For example, using linked employer-employee data for the UK, a study finds that employee well-being is generally negatively related to job demands and positively related to job control, as predicted by the demand–control theory [3]. Also, high job control weakens the negative link between job demands and employee well-being. However, studies that focus on the effects of specific high involvement management practices reveal that they are often associated with high levels of work intensity and perceived worker stress, even when they are also associated with a higher work commitment or higher job control [4].

Survey data for the late 1990s show that task discretion declined in most European countries. In the UK, this declining task discretion and the intensification of work effort were associated with a notable reduction in the level of job satisfaction [5]. This declining trend has been reversed in more recent years. In the UK, high involvement management was introduced as part of a lean production system that aimed to reduce costs and support just-in-time production at the plant level. Just-in-time production is associated with weaker sick leave provisions [6], as predicted by a theoretical model of worker reliability [7].

In summary, the empirical findings from these studies point to a connection between high involvement management and reduced employee well-being and higher rates of occupational accidents and absenteeism. However, other UK studies suggest that high involvement management supports greater perceived satisfaction at work. In particular, there is convincing empirical evidence that performance-related pay significantly improves perceived job satisfaction [8].

The evidence for countries in continental Europe is also ambiguous about the effects of high involvement management on various aspects of employee well-being. Evidence for France shows that high involvement management is positively associated with mental strain and employee perceptions of occupational risks, but not with occupational accidents [9]. A recent empirical study of a large German steel plant supports the conclusion that high involvement management significantly increases accidents and absenteeism by increasing labor intensity [10]. The introduction of work team production bonuses leads to an increase in absenteeism and in the number and severity of occupational accidents. Evidence based on European data relates performance-based pay such as piece rates to increased injuries in the workplace. But the empirical evidence is far from conclusive. For example, a study using representative Finnish survey data finds that high-performance workplace systems have little impact on the overall health of employees [11].

Causality and the identification problem

The most important challenge in interpreting the estimates from the empirical studies noted above is to establish whether the relationship between high involvement management and employee well-being is causal or not. The estimates are difficult to interpret because high involvement management jobs are more demanding than other types of jobs and could therefore attract healthier, more able, or more mentally or physically resilient employees. Such workers may be more likely to queue for high involvement management jobs, and employers are more likely to offer these employees high involvement management jobs.

Failure to account for the self-selection of more able and healthier workers into high involvement management jobs will upwardly bias the estimated effect of these management practices on employee well-being. That is because the well-being of employees in firms that practice high involvement management would have been higher than that of their counterparts even in the absence of such management practices.

Market and job search frictions and imperfect information about available job vacancies imply that employees cannot shift easily between high involvement management companies and companies that do not apply such practices without facing substantial costs. As a result, their current employment will not necessarily reflect their underlying preferences concerning high involvement management practices. Thus, the self-selection of employees into workplaces and job tasks remains a source of potential estimation bias.

A further limitation on any causal interpretation of the relationship between high involvement management and various measures of employee well-being concerns non-observable characteristics of workers and omitted variable bias. Employees in high involvement management companies and those in other companies may differ in dimensions other than their work and health histories that are unobservable in the data but that may influence both workers’ propensity to take jobs in high involvement management companies and their current state of physical and mental well-being. For example, risk preferences and personality traits are not observed in most data. But employees with high risk preferences may be more willing to take on the more demanding and responsible tasks in a high involvement management job and also may be more likely to engage in risky behavior such as smoking and alcohol consumption that has harmful effects on their health. If this is the case, then there would be a negative bias in the estimated effects of high involvement management on measured employee well-being.

Omitted variable bias might also arise from unobserved differences between high involvement management jobs and other jobs. For example, high involvement management jobs may be better jobs in terms of their overall compensation or physical and mental working conditions. In that case, working in high involvement management companies might improve employee well-being for reasons that have nothing to do with the amount of employee involvement they offer.

Using linked survey and register data

Using linked data to study the impact of high involvement management on employee well-being and health provides a methodological advance over previous empirical approaches. Because of the unobservable employee characteristics referred to above—such as abilities that are significantly related both to the entry into high involvement management firms and subsequent well-being at the workplace—it is challenging to present compelling evidence on the causal impact of such management practices on employee well-being. Thus, the key problem in empirical research is that employees are not randomly assigned to high involvement management companies. This lack of random assignment may substantially bias the estimates of the impact of high involvement management practices on employee well-being. At least some of the impact on well-being is likely a result of less able employees being less capable in high involvement management jobs, perhaps creating greater stress for them on the job. The size of this bias is unknown.

One approach to alleviate this problem is to find a set of variables describing wage and work histories that are plausibly highly correlated with unobserved employee traits, thus reducing the scope for omitted variables bias.

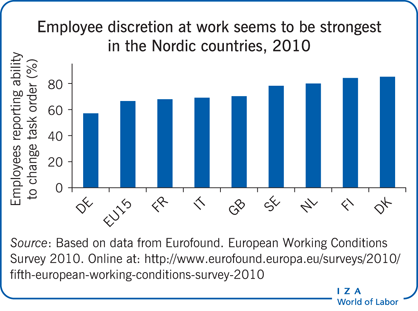

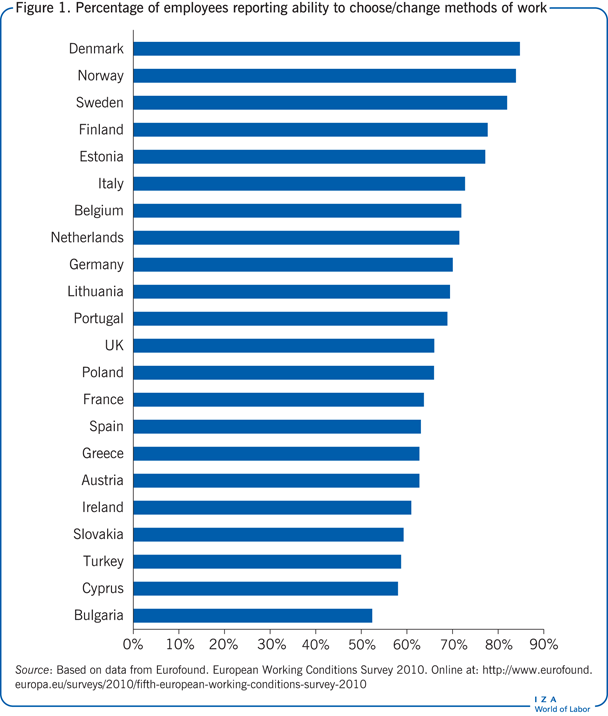

One study took advantage of a representative Finnish survey and register data, linking the data to estimate the effect of high involvement management on subsequent wages and employee well-being [12], [13]. The Finnish case is interesting for its analysis of high involvement management, because Finland is renowned for being an “early mover” in these management practices. Large firms in the export-oriented manufacturing sector have been in the frontline in adopting high involvement management. From a broader perspective, the Nordic countries are an interesting setting to examine the effects of high involvement management. These countries have widely adopted various aspects of these management practices (as compared to other countries: see Figure 1), and the institutional framework in the labor market, where employer-employee cooperation is common, may also support the positive effects of these practices on employees.

The primary data used in the analysis are from Statistics Finland’s Quality of Working Life Survey of 2003 [12], [13]. The survey is administered through face-to-face interviews that cover all major aspects of respondents’ employment. In addition to information on the high involvement management practices that a worker is exposed to in the workplace, the survey also contains rich information about various dimensions of employee well-being and health at work.

The most important limitation of the Quality of Working Life Survey is that it is a cross-section data set. Thus, it includes only some rough self-reported information on past labor market experience, such as length of time working in the current firm. However, it is possible to overcome this lack of information on past labor market information and link the survey data with comprehensive longitudinal register data maintained by Statistics Finland: the Finnish Longitudinal Employer-Employee Data. This longitudinal data set is constructed from a number of registers on individuals and firms that are gathered and maintained by Statistics Finland. The survey and register data sets can be linked through unique personal identifier codes. The codes can then be used to follow individual employees backwards over the period 1990–2003 to link information on the firm and establishment to each individual each year. The wage and work history variables that can be constructed using the comprehensive register-based Finnish Longitudinal Employer-Employee Data include duration of past employment and unemployment spells, number of layoff episodes, past average earnings (1990–2001), and past earnings growth. All of these work history variables are linked to the Quality of Working Life Survey through the longitudinal register data.

After controlling for standard individual-level variables such as educational attainment that are basic determinants of employee compensation, the study calculated a wage premium of roughly 20% for high involvement management jobs [12]. The estimate of the wage premium falls by around one-fifth when comprehensive controls for wage and work histories are added to the model as explanatory variables. These variables, which are jointly statistically significant determinants of employee entry into high involvement management companies, were absent from earlier empirical studies. This observation points to an upward bias in previous empirical studies of the wage returns to high involvement management due to positive self-selection of employees into such jobs. This kind of self-selection is arguably associated with hitherto unobserved differences in employee quality. However, even with a rich set of controls related to wage and work histories, it is very unlikely that estimates of the effects of high involvement management have been purged of all potential bias associated with employee ability.

Using the same Finnish linked survey and register data, but adding register-based information on employees’ histories of sickness-related absences, estimates show that the association between high involvement management practices and various facets of employee well-being is generally positive and economically significant (meaning that they have large positive effects) [13]. In particular, high involvement management is strongly associated with higher evaluations of subjective well-being, including higher satisfaction at work and lack of fatigue. High involvement management is also significantly associated with a reduced prevalence of accidents in the workplace.

It is quite possible that these positive effects stem from the close cooperation between employees and employers that is prevalent in the Finnish labor market. Finland seems to differ from the UK, where the association between high involvement management and labor intensity is more evident. However, even in the Finnish labor market, some aspects of high involvement management exposure—especially performance-related pay and employer-provided training—are significantly associated with a higher incidence of short-term sickness-related absences.

There is a plausible explanation for the increase in the number of short-term sickness-related absences [13]. Work is more demanding in the firms that adopt high involvement management practices. To compensate for this greater complexity, employees in these firms are multi-skilled and employees’ skills are improved through employer-provided training. This implies that employees can cover for one another’s short absences more easily. Thus, the costs of replacement labor for the employer are also lower. For this reason, it may be economically reasonable for a firm to pay the additional short-term cost of absences caused by employee tiredness if it also means that the firm is able to meet tight production schedules. It is also interesting to note, that high involvement management is positively related to both wages and employee well-being, which is in contrast to the idea that employees are compensated with higher wages for experiencing various harms at workplaces.

Limitations and gaps

There are several important limitations in the empirical literature on high involvement management. The use of subjective measures of well-being may pose difficulties in interpreting the estimates. The evidence on the relationships between high involvement management and employee well-being is both scarce and based mainly on case studies of particular occupations or self-selected samples of employees. The reliance on case studies reflects the fact that representative data sets containing information on both participation in high involvement management jobs and employee outcomes (well-being and health) have been lacking.

The case-study approach can be highly problematic because the effects of various aspects of high involvement management practices likely differ across different types of firms or industries. The firms and industries that have drawn researchers’ attention may be those where the positive effects of high involvement management on employee well-being would be expected to materialize because their characteristics are consistent with the theory on such an association. This makes it difficult to extrapolate from these empirical patterns to the population of all firms and employees. The effects can also be different in different institutional settings.

The use of linked survey and register data is a promising approach to gain deeper knowledge about the impacts of high involvement management on workers’ well-being. Future research on these issues would also benefit from register-based firm-level data. This could alleviate the problem of differences in unobservable characteristics between firms that practice high involvement management and those that do not, which can simultaneously affect both wage formation and the propensity to adopt such management practices.

Summary and policy advice

There are empirical studies that aim to link high involvement management to various aspects of employee well-being. But only recently have there been studies that account for comprehensive employee wage and work histories. This is important because the estimates show that employees’ wage and work histories are a significant predictor of subsequent entry into a high involvement management job. Despite the fact that not all effects point in the same direction, there are clear indications that more able employees—as described by their histories of past earnings and earnings growth—are more likely to enter high involvement management jobs.

There are several important issues that have to be taken into account before drawing strict policy conclusions about the findings in the empirical literature on high involvement management practices. There is still relatively sparse information about the exact costs and benefits of high involvement management practices in specific settings. It is particularly important to gain more knowledge because such management practices are often costly for firms to adopt. The costs and benefits seem to differ considerably across firms, and they are also dependent on the institutional framework that has been adopted in the labor market.

The evidence supports the conclusion that cooperation between employers and employees may be a particularly important condition for the full benefits of high involvement management practices to materialize for both firms and employees. However, it is not easy to establish cooperation between employers and employees in institutional settings where there is no tradition for seeking mutual benefits in the labor market. Cooperation is a long-term investment.

It is also important to use representative data to examine the effects of high involvement management practices, because the effects can be widely different between firms. It is not easy to generalize the results from a specific set of firms to the total population of firms and employees. Furthermore, recent empirical studies show that the use of linked survey and register data is important, because linked data make it possible to take into account the self-selection of employees into high involvement management practices. Otherwise, the estimated effects are biased, and it is not possible to draw reliable policy conclusions.

Thus, while there is still a lot to be learned about the effects of high involvement management practices in different institutional settings, a tentative conclusion can be drawn from the empirical evidence. Even after employee self-selection is taken into account, the effects of high involvement management practices are generally positive, suggesting that firms may want to invest in these practices, which seem to improve employee well-being as well as firm outcomes, at least in Finland, where employer-employee cooperation is common.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. He is also grateful to Alex Bryson and Pekka Ilmakunnas for very useful comments.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Petri Böckerman