Elevator pitch

Measures of individual happiness, or well-being, can guide labor market policies. Individual unemployment, as well as the rate of unemployment in society, have a negative effect on happiness. In contrast, employment protection and un-employment benefits or a basic income can contribute to happiness—though when such policies prolong unintended unemployment, the net effect on national happiness is negative. Active labor market policies that create more job opportunities increase happiness, which in turn increases productivity. Measures of individual happiness should therefore guide labor market policy more explicitly, also with substantial robotization in production.

Key findings

Pros

Unemployment has a significant negative effect on individual happiness and is comparable to personal trauma such as divorce or a death in the family.

Employment protection policy for permanent jobs contributes to happiness.

Unemployment benefits contribute to happiness.

Policies designed to increase employment opportunities also increase happiness.

Policies aimed at reducing income inequality, such as minimum wages, will increase happiness.

Cons

The pain and subsequent unhappiness of losing a job is not fully compensated for by finding another job, unless this occurs seamlessly.

Employment protection can increase unemployment for “outsiders” and hence be associated with unhappiness.

Favorable unemployment benefits may prolong unemployment and thereby reduce happiness.

Minimum wages may reduce happiness if they lead to more unemployment.

Happiness-increasing policies have winners and losers, so there is risk to governments in introducing happiness-increasing policies.

Author's main message

Society should be organized to foster personal happiness and well-being. Employment is central in this context and happiness at work increases productivity, whereas unemployment has negative effects on long-term happiness. Policies that reduce unemployment can thus increase happiness; but, the timing and targeting of such policies is important. Robotization may decrease employment of certain groups with possible concomitant loss in happiness. So to ensure national well-being and greater productivity, governments should put full employment center-stage.

Motivation

Economists and politicians are increasingly convinced that “happiness,” which in this context means personal well-being and satisfaction with life (as measured in happiness research), may be as important for evaluating and determining labor market policy as the more traditional measures, such as GDP per capita or unemployment.

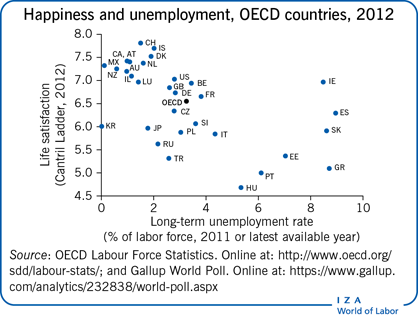

Conversely, labor market policies also have an impact on happiness, as lower unemployment in a country is associated with more happiness (see the Illustration). The global financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent high levels of unemployment have spurred the international debate regarding the ways and means of regaining (close to) full employment. In many European countries, this debate centers on “structural labor reform”; i.e. reductions in employment protection legislation for workers with permanent contracts and reductions in the size and duration of unemployment benefits. Both of these measures would have considerable impact on the happiness and well-being of those affected. In the post-crisis period (after 2014) concerns about employment are gradually shifting toward the impact of robotization on the level of employment, with ample debate on unconditional basic income as a means to enhance happiness in periods with substantial unemployment.

There is also considerable debate on the impact of active labor market policies (i.e. policies designed to create job opportunities for the unemployed) in situations when the unemployed accept jobs for little pay and few prospects for promotion. Poorly paid, not secure, part-time jobs with limited and no control over schedules are a threat to happiness, also the risk of unemployment resulting from robotization is substantial.

Labor market policies, in particular minimum wage legislation, can also affect the income distribution. The impact of minimum wage legislation on happiness is then likely to be the net result of the positive impact on wage inequality and the negative impact through unemployment it can give rise to. One study in particular shows how labor market policies can be evaluated along the happiness criterion in order to develop a scenario in which full employment is regained in the EU by 2020, and where income inequality is reduced and economies made more sustainable [1].

Technological advancements, however, give rise to substantial “creative destruction” and new types of employment practices. One US study shows how the effect on happiness depends on the speed of mobility and that of labor market price adjustment [2]. Some see this as irrevocably calling for a basic income to invite voluntary unemployment [3].

It is vitally important that policymakers understand the connections between particular policy measures and their effects on people's sense of happiness and well-being.

Discussion of pros and cons

What is happiness and how is it measured?

Almost every language has an expression along the lines of “money can't buy you happiness.” Yet it wasn't until the early 1970s that economists began to consider trying to measure the extent of people's happiness, their state of well-being, and satisfaction with life, in terms other than of their monetary wealth or current income [4].

Around the same time, sociologists began to conduct questionnaires with individuals in order to assess their general state of happiness and satisfaction with life: e.g. whether people considered themselves to be “happy,” “pretty happy,” or “not very happy.” The results turned out to be quite robust, with little variability across periods of time. The score on an individual's self-report would also be corroborated with reports provided on the person through other means, or through evaluations provided by outside observers. These would include observations of stress levels, facial expressions, as well as brain scans [4].

Happiness measurements are now based on assessments over time, rather than being short-term, and their value is increasingly recognized by economists and politicians as being an important guide for policy evaluation.

The effect of unemployment on happiness

Of all the external factors that might influence an individual's sense of happiness and well-being, unemployment is by far the most significant. Being unemployed, or being made unemployed, is comparable in its effect to other more personal factors or trauma that can influence an individual's sense of well-being, such as divorce or a death in the family [5].

Being employed is a very important contributory factor in determining an individual's sense of happiness and well-being. And this is the case even when other external factors have been taken into account, such as the level of corruption in society, the degree of freedom in the country, or the social support systems that are in place within the individual's environment.

Measures of happiness are related to a number of factors, including an individual's situation in the labor market. The work that people do and the conditions under which they work, as well as the income they earn through their work, or the loss of a job and the difficulties in finding a job, and so on, all have a clear and significant impact on individual happiness [5].

However, individual happiness is also linked to wider employment circumstances within a country. For example, it is not only an individual's state of unemployment that causes them unhappiness, but also the rate of unemployment in a country, to the extent that the total loss of happiness due to a rise in the unemployment rate is twice as large as the loss to the individuals who lose their job (measured by the Life Satisfaction Scale used for the Illustration [4]). In other words, people feel for others and are more depressed by the general situation. This understanding should stimulate governments to promote the policy goal of (near) full employment on par with (sustainable) economic growth, controlled inflation, and fair income distribution.

When people become unemployed they experience sharp falls in happiness and well-being [5]. Well-being remains at this lower level until they are re-employed. This reduction in well-being is not so much a result of the loss of income, but more as a consequence of the factors associated with being “in work,” such as social status, self-esteem, workplace social life, as well as the routine and time structure of the working day. Other important factors that contribute to reduction in well-being include: the loss of regularly shared experiences and contacts with people outside the family; links to collective goals and purposes that transcend the individual; individual status and identity; and the enforcement of activity [5].

The pain and subsequent unhappiness of losing a job is not fully compensated for by finding another job. Unemployment leaves scars. Early adult unemployment, in particular, turns out to have long-lasting effects, not only in terms of happiness, but also in labor market outcomes like wages.

Happiness is generally lower not only for the current unemployed (relative to the employed), but also for those with higher levels of past unemployment. Therefore, labor market policy should ideally be geared toward mobility, so that a new job is found before the current job is lost. Employment protection policies may sometimes give the illusion that the job is there to stay, even if all evidence suggests differently.

Modern technological advancements, in particular the rapid increases in the speed of computer chips (“Moore's law”), combined with the speed of connectedness and artificial intelligence, have brought significant changes in the speed of creative destruction and the types of employment available.

Does employment protection increase happiness?

A traditional dilemma in labor market policies is that the “insiders” (i.e. workers with attractive labor contracts and well-developed safety nets in case of unemployment) will not easily abandon their privileges even if it would mean that the “outsiders” (those who cannot find employment, who are often the young, less educated, and/or less skilled) would gain more than the “insiders” would lose.

Labor market institutions have an effect on happiness. On the labor demand side, these institutions generate a high-quality work environment through legislation that provides job security and working terms and conditions that are considered pleasant and attractive. Some 20% of workers in OECD countries state in surveys that a high income is very important, as are flexible hours (20%) and promotion opportunities (20%). But around 60% say that job security is very important, with similar figures for interesting work and autonomy (50% and 30% respectively) [6].

In other words, reducing employment protection is likely to reduce the happiness of those who are covered, or who are expected to be covered in the (near) future by this protection. In general, workers feel more secure when protection legislation—as measured by the OECD in employment protection legislation—is stronger.

Over the period 1994–2011, job security, as expressed in firing costs, indeed improved well-being (measured by job-satisfaction) of permanent workers, as would be expected [7].

However, the effect is small and often not particularly significant. In the same way, temporary workers experience more well-being when permanent workers are better protected, as presumably they see themselves in that position in the near future.

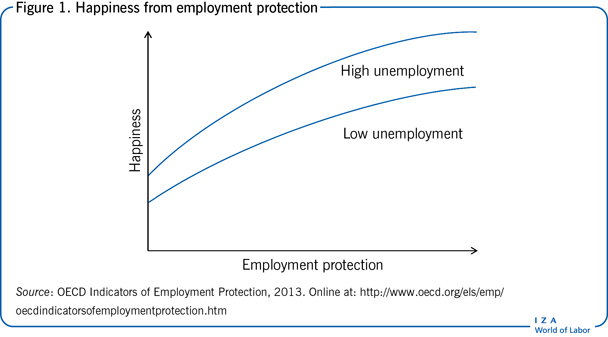

Permanent contract workers in Europe in the period 1995–2005, however, did not increase their life happiness with an increase in employment protection, but temporary workers did. It is interesting to note that the importance of employment protection for happiness for workers under a permanent contract decreased in this period of decreasing unemployment [8]. It appears that the extra happiness derived from employment protection is as sketched in Figure 1, which shows happiness diminishing with an increase in protection, and higher in periods of rising unemployment than in periods of declining unemployment.

Workers’ well-being matters to firms as well as to workers, as it is a good predictor of productivity. It is commonly accepted that the workers who are more satisfied with their jobs are less likely to quit from them. They are also less likely to reduce firm productivity via absenteeism, or via “presenteeism”: turning up to work, but contributing little.

Labor market institutions also deal with job safety and health risks at work. These have a positive impact on happiness, as individuals value their personal health highly when expressing how happy they are. Workers in highly stressful jobs, who don't receive adequate support to cope with difficult work demands, are more likely to suffer from job burnout, or to develop musculoskeletal disorders, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, among others. Highly stressful jobs are, in fact, relatively widespread.

Job quality is therefore an important issue for labor policy that is also guided by happiness. However, happiness-increasing policies, such as employment protection, can also be associated with unhappiness as a result of increasing unemployment for the “outsiders.”

Unemployment in a country following an economic shock, as was experienced in the wake of the 2008 crisis in Europe and the US, is first and foremost the result of decreased investment and reduced spending. Yet the impact of labor market institutions, such as employment protection or unemployment benefits, or the confluence of education and work (as in the German dual education system), matter considerably during the adjustment to the new circumstances.

If Spain had the same employment protection as France did at the outbreak of the crisis, then its unemployment would have been half the 2012 level [9]. At the same time, Spain experienced such a strong rise in youth unemployment that experts now believe that a generation may be “lost”; while in Germany, youth unemployment continued to decline and was hardly affected by the crisis. These differences coincide with different structures of labor market policy and in the transition from school to work, which for many young people in Germany is eased by the dual vocational education system [10].

By 2018 the labor markets in Europe and the US have more or less recovered from the impact of the crisis, and full employment in many EU countries and in the US is now within reach. At the same time, the consequences of the fast information and communication technology (ICT) revolution—often dubbed “the third industrial revolution”—on employment are becoming visible, potentially with substantial unemployment, either transitory or permanent, while at the same time affecting the type of employment in terms of security and health provisions. This has led to suggestions of a basic income as a way to reduce the supply of labor, so that full employment can still be guaranteed [3]. The 2018 World Economic Forum gave serious thought to basic income as a policy option. The consequences of different policies in terms of happiness need further exploration.

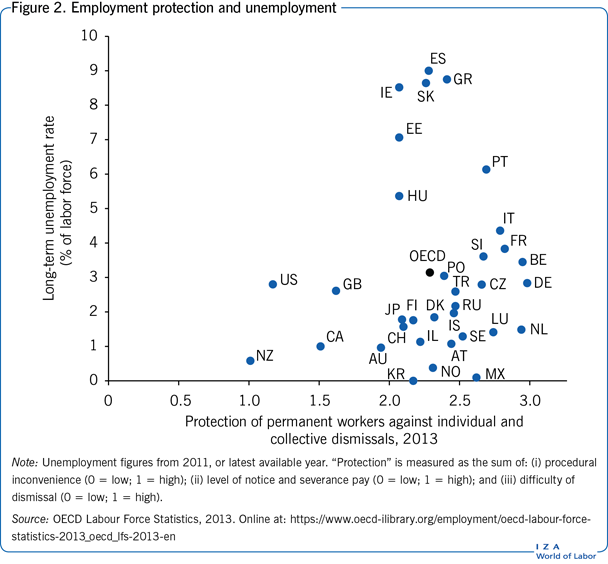

Employment protection legislation and labor mobility

Employment protection has a sizable effect on labor market flows and these, in turn, have significant impacts on productivity growth [11]. At the same time, some displaced workers lose out via longer periods of unemployment and/or lower real wages in post-displacement jobs. OECD countries fare differently along the employment protection-unemployment axis (Figure 2).

Employment protection legislation may reduce mobility from declining industries to growing industries (or within firms from disappearing jobs to newly emerging jobs) by raising labor adjustment costs. It may also have negative implications for aggregate economic and labor market outcomes. High-risk innovative sectors are relatively smaller in those countries with strict employment protection legislation. This may explain a considerable portion of the slowdown in productivity in the EU relative to the US since 1995 and the lower level of “yollies” (young leading innovators) in Europe compared to the US.

Employment protection legislation has a significant negative effect on unemployment turnover, on job-to-job flows and on mobility. It has been noted in one study, for example, that switching the employment protection legislation in Spain to be similar to that in force in Finland resulted in an increase in overall labor mobility of four percentage points [6]. At the same time, job stability may encourage work commitment and investment in firm-specific human capital (e.g. firm-sponsored training schemes) with a positive impact on productivity and real-wage growth [1].

In many European countries, regulation surrounding temporary contracts of employment has been “liberalized,” or become more relaxed, over the last two decades, while remaining stringent for permanent contracts. The effect of this has been to push firms into substituting temporary workers for regular workers. Those employed on temporary contracts (often younger people and other workers with little work experience or low skills) then have to bear the impact and consequences of the employment adjustment. Also, employment protection in the form of firing costs for permanent workers contributes to hiring more temporary contract workers when firms are faced with uncertain futures. And for start-ups and firms in their initial stages, uncertainty is a characteristic feature of their existence.

In summary, then, the main policy question in relation to employment protection is to weigh up the “pro” of more happiness (due to the increase in employment) against the “con” of more unhappiness as a result of less employment protection for those concerned.

The dual effects of unemployment benefits on happiness

Unemployment benefits contribute to an individual's income, which in itself is happiness-increasing. Yet they provide little compensation for the unhappiness experienced due to the loss of the job in the first place. In addition, unemployment benefits may cause the period of unemployment to increase.

The longer the period of substantial unemployment benefits, the longer the duration of unemployment. The evidence on this relationship is overwhelming, most recently from many states in the US, where unemployment benefits were extended during the period 2009–2012. There was a small but statistically significant reduction in the unemployment exit rate and a small increase in the expected duration of unemployment.

The system of so-called “flexicurity,” which seeks to combine labor market flexibility with security for workers through providing high unemployment benefits for a short period combined with less employment protection, is generally considered to generate the same degree of happiness as low benefits for a longer period with high employment protection [8].

Creating more job opportunities contributes to happiness

For Germany, not a single job feature or combination of such features could be found such that remaining unemployed would be the better choice for the individual. The evidence shows that even the opportunity to take on lower-quality jobs is associated with higher life â(satisfaction [12].

This conclusion corresponds with findings from the country's workfare program: being employed makes the individual happier than not being employed while receiving a social security benefit that is not much lower than the earnings that could be gained from employment.

Policies aimed at creating additional employment in the public sector and—through subsidies—in the private sector for those in danger of remaining unemployed for extended periods are clearly happiness-enhancing. This is likely to remain the case when the possible decrease in happiness as a result of additional taxation for these jobs is taken into account.

Income and wealth inequality create unhappiness

For most people, the major function of work is to earn an income. Within countries, people with higher incomes are generally happier (if all other circumstances, such as age, health, and education are the same). In contrast, across countries, average income per person is not so strongly related to average happiness in that country. Also, over time, happiness does not necessarily go up in a country when average income per person increases. This is referred to as the Easterlin paradox, which notes that while high incomes do correlate with happiness, long-term increased income does not correlate with increased happiness. Or, put differently, individuals derive their happiness from their income relative to that of others.

As a result of this, the variation of happiness across the world's population is largely seen within countries, even though the levels of income might differ substantially between countries. Twenty-two percent of the worldwide variation in one measure of happiness (the Gallup World Poll ladder) is between countries. This is much lower than the corresponding 42% variation in household incomes between countries [5]. The primary reason for the difference is that income is but one of the causes for happiness, while most of the other causes, such as the population's health, are much more evenly spread across countries.

During the period 1975–1992, European people had a higher tendency to report themselves happy when inequality was low, even if their own income might have been high [13]. However, this effect may not be so apparent in the EU over recent years.

Relative income differences in Latin America, however, which is the region with the highest inequality in the world, have large and consistent effects on well-being. In Latin America, inequality seems to be a signal of persistent advantage for the very wealthy and persistent disadvantage for the poor, rather than a signal of future opportunities.

The effect of minimum wage policy on happiness

Income inequality is to a large extent the result of wage inequality. Policies directed at the reduction of wage inequality are in this respect happiness-increasing. Minimum wage policy may increase the happiness of those who are employed at that wage level, but may also reduce happiness, as employment might shrink and unemployment increase as a result. Minimum wages can therefore reduce happiness if they lead to more unemployment.

An increase in the minimum wage generally does not lead firms to fire or lay off workers they already have, but does reduce the rate at which new workers are hired, depending on the stage in the business cycle. Countries with minimum wages fare worse in times of economic downturns than those without, depending on the level of the minimum wage for adult and young workers [1].

Robotization

Discussions on the implications of the vast transformation of the world of work due to the third industrial revolution are in full swing [14]. Some studies suggest persistent long-term unemployment of workers with low and medium level skills, even when active labor market policies are taken into account [15]. Others believe in labor market adjustments which are able to provide for full employment with the help of policies [14]. What is common among all observers and analysts is that the speed of “creative destruction” is increasing, making “seamless mobility” a necessity to retain happiness from employment under robotization [2]. Creative destruction refers to the incessant product and process innovation mechanism by which new production units replace outdated ones.

Basic incomes would be happiness increasing, if they would be set at a level comparable to present-day social assistance. However, affordability is unlikely without a substantial tax increase and the associated happiness decrease. But even if basic incomes were affordable, then there are questions about their long-term happiness effect. First: work is more than the income it generates. It provides for a social structure. Second: the choice for a basic income would be free to the individual. However, there is no guarantee that employment will be available for the same individual when they decide to seek employment, as skills tend to degrade when not used. A basic income then becomes a trap: easy to get into, but difficult to get out of.

Timing happiness-increasing policy changes

Happiness-increasing policies will have winners and losers. The losers are likely to pose a risk for the politicians who decide to implement happiness-increasing policies.

The best time for governments to reduce employment protection and the duration of unemployment benefits is at the height of the business cycle. This is when unemployment has been decreasing and is at a low point. The resistance against such changes will therefore be low and the happiness “decrease effect” of such measures would be limited.

At the same time, however, the happiness “increase effect,” due to lower unemployment, is also limited. Hence, most OECD countries tend to increase, or at least not decrease, employment protection and unemployment benefits in the upswing of the business cycle rather than at the height. This strategy, however, makes them less prepared for the downswing in the business cycle and the subsequent increase in unemployment.

During the downswing in the business cycle politicians have less support for downward adjustments as they hurt permanent workers as well as the unemployed. A political majority is then not so easily achieved, even if the long-term impact can be argued to be positive in terms of employment and happiness. The rights of the “ins” in this situation will be defended, while the voices of the “outs” will count for less.

Limitations and gaps

There are a number of limitations to the use of happiness as a means of evaluating labor market policy in a country. The data and insight presented in this contribution on the relationship between happiness and employment protection, or unemployment benefits, are at present scattered and far from complete. For example, individuals are likely to change their view on employment protection or unemployment benefits, perhaps as a result of changing labor market conditions. This appeared to be the situation during the period prior to the Eurozone crisis when unemployment in Europe was decreasing (Figure 1).

A better quantification of the relationship of happiness to employment protection and unemployment benefits would be very helpful for policy making. Figure 1 also indicates that the relationship between employment protection, or unemployment benefits, and happiness is likely to be non-linear, as is depicted for employment protection. The same holds true for the relation between (un)employment, on the one hand, and employment protection and unemployment benefits on the other.

As a result, the findings in the current empirical literature are limited and need to be brought together in a more detailed quantified picture. Panel data, which would necessarily include observations and analysis over time and across sectors (such as for individuals, firms, households, and so on) would be an important next step.

Summary and policy advice

Labor market policy affects individual and collective happiness, particularly via its impact on the level of unemployment. Happiness of the working population in turn contributes toward a more productive economy. If a government wishes to ensure the greatest happiness of its people, it should therefore put full employment center-stage among its economic policy goals.

Unemployment has long-term negative effects in terms of happiness for individuals—particularly the young—and for society as a whole. Labor market policies such as employment protection legislation and unemployment benefits increase happiness, but they also contribute to unemployment (and its associated unhappiness).

Further, it is likely that policies to reduce employment protection for those with permanent contracts and policies to reduce the duration of unemployment benefits may increase national happiness overall, as they help to reduce unemployment. However, such policies are difficult to enact in periods of high unemployment. In order to address this dilemma, policymakers should consider implementing more targeted, accommodating actions, such as increasing employment protection for temporary workers and providing special arrangements for the long-term unemployed and older workers. The long-term unemployed can be released from job-searching and still be eligible for financial support if they perform voluntary work. Older workers with low chances of finding work can be accommodated with financial support toward retirement. Many countries have recently successfully experimented with such policies.

Active labor policies such as workfare programs also increase happiness, even if the jobs are not “ideal” in terms of pay and promotion prospects. Greater inequality in incomes is associated with less happiness. Labor market policies to reduce wage inequality should take this into account. Limitations on top incomes in non-entrepreneurial jobs may have an impact on income inequality, with a likely positive happiness gain within the country.

Finally, happiness-guided labor market policy would set the level of the minimum wage carefully in order to avoid an increase in unemployment. Minimum incomes are not only determined by wages but also by tax breaks for workers (as a fixed amount). In view of this, a negative income tax at the bottom end of the income distribution might be superior, in terms of the happiness it induces, to a high minimum-income level.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author would also like to thank Vanessa Draeger. Financial support of IZA and the Rockefeller Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Version 2 of the article adds discussion on robotization and unconditional basic incomes and four new key references [2], [3], [14], [15].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Jo Ritzen