Elevator pitch

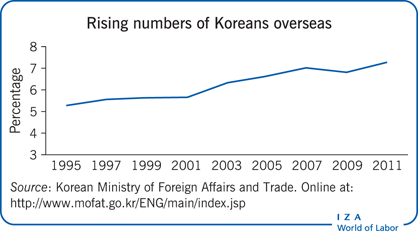

Since the 1990s, South Korea’s population has been aging and its fertility rate has fallen. At the same time, the number of Koreans living abroad has risen considerably. These trends threaten to diminish South Korea’s international and economic stature. To mitigate the negative effects of these new challenges, South Korea has begun to engage the seven million Koreans living abroad, transforming the diaspora into a positive force for long-term development.

Key findings

Pros

The Korean diaspora continues to grow and now exceeds 7.2 million (11% of the population in 2011).

South Korea is strengthening its ties with Koreans overseas.

In the 1990s, South Korea began to view its diaspora as a valuable asset for the nation’s future.

There is now substantial economic cooperation between businesses in South Korea and those operated by Koreans outside the country.

Brain drain was a concern in the 1960s and 1970s, but South Korea and China are now experiencing the return migration of scientists and engineers.

Cons

Some people oppose engaging the diaspora because Koreans abroad do not fulfill certain civic duties (such as paying taxes and completing military service).

Recognition of dual citizenship has encountered resistance because of South Korea’s strong nationalist tradition.

South Korea’s diaspora engagement policy might be seen as fundamentally ethno-nationalistic.

China, with two million Koreans in its territory, is concerned about South Korea’s policy.

Author's main message

Responding to transnationalism and a shrinking population, South Korea has pursued a policy of engaging its seven-million-strong diaspora by giving Koreans living abroad virtual extraterritorial citizenship. The policy is yielding economic benefits, as well as the political and cultural benefits that stem from building loyalty to the ethnic homeland. The government’s Overseas Koreans Foundation is fostering a Korean identity among the diaspora, enhancing and expanding economic and political cooperation with them, and building networks linking them to one another and to Koreans in South Korea.

Motivation

Since the 1990s countries have been facing challenges from globalization and transnationalism. Transnationalism is increasing, as a rising number of people worldwide engage in activities that take them across national boundaries, moving from one country to another. This has made it more complicated for countries to govern themselves, especially when it has contributed to a shrinking population.

South Korea is one of these countries, facing a demographic crisis and the effects of transnationalism. It has a rapidly aging population (aging even faster than Japan’s), a falling fertility rate (the lowest among all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries), continuing outmigration of its middle class, and slowing economic growth. In addition, increasing numbers of foreign residents threaten the country’s identity, built as it is on ethnic homogeneity and the goal of reunifying as one nation. This is the context in which the country decided to reconnect itself to its seven-million-strong globally scattered diaspora. How can this be achieved?

Discussion of pros and cons

Overpopulation and poverty were major challenges for South Korean policymakers in the 1960s when they inaugurated the country’s new industrialization program. In the early 1960s, South Korea had 27 million citizens and a per capita GDP of only about US$100. By 1970, the country’s population had grown to 32 million, and by 1980, it exceeded 38 million. As the effects of the industrialization program took hold, the population streamed from rural to urban areas. The country’s urbanization rate soared from about 30% of the population in the early 1960s to 70% by the 1980s. As part of its national development policy, South Korea also took two other key steps:

To cope with overpopulation, the government launched an intensive family-planning program in 1962.

It began an active program of sending workers overseas, both to relieve population pressure and to earn foreign currency.

By the end of the 1980s, the situation had changed dramatically. Male migration from rural areas to urban industrial centers had already run its course by the early 1980s. Female migration from rural areas continued, however, resulting in severe gender imbalances in rural areas.

Later, men in rural areas began to search for mail-order brides, marrying women from other countries. In South Korea’s urban areas, the labor supply tightened and wages rose. Labor shortages became so severe, particularly in low-paying blue-collar jobs, that by the end of the 1980s Korea was encouraging migrant workers from less developed Asian countries to enter the country.

Meanwhile, the population was aging rapidly, and economic growth had slowed. In addition, the fertility rate had settled at around 1.2 births per woman for the previous ten years, well below the population replacement rate. With the combination of an aging population and a low fertility rate, the country’s population was projected to start falling in 2030. This set off alarm bells for policymakers, who only two decades before had worried about overpopulation and had encouraged family planning and overseas migration.

Outmigration continued, especially among middle-class families. Although the number of emigrants fell after the 1980s, many middle-class families still leave to pursue better lives and enjoy the less competitive educational environment in other countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the US. Meanwhile, the number of non-native residents in South Korea, many of whom came to the country as migrant workers or mail-order brides, continues to grow. This poses another challenge to South Korean society, which used to be one of the world’s most ethnically homogeneous countries.

All these trends have contributed to stagnating economic growth since the 1990s. The country’s economy grew rapidly through the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, but the growth rate stagnated after 2000. This raised fears that the country’s industries might be overtaken by industries in the emerging market economies, such as its gigantic neighbor China.

These challenges pushed the country to find answers from every possible source. One such opportunity was the seven million Koreans of the diaspora. Scattered all over the world, their size is equivalent to almost 11% of the Korean population.

Engaging with South Korea’s diaspora

Not until the early 1990s did the South Korean government begin to pay serious attention to its diaspora, including the two million Koreans in China and the half million in the former Soviet Union. In the early 1990s, however, the government began to view the Korean diaspora as an asset that was especially valuable in a rapidly globalizing world. Investing in the diaspora was seen as an investment in South Korea’s future.

The government’s statistical data for 1991 reflected this new view: ethnic Koreans in China and the former Soviet Union were included for the first time in the official “Overseas Korean” statistics. Following the “Nordic Policy,” in which South Korea pursued normalization of diplomatic relations with the former communist countries of China and Russia, the South Korean government began to engage with ethnic Koreans in these countries, providing them with Korean language education support and opportunities to visit their homeland.

By the mid-1990s, the government had become much more active and systematic in its diaspora engagement policy. It established the Overseas Koreans Foundation (OKF) in 1997 to strengthen the connection between diaspora Koreans and their ethnic homeland and to help them settle successfully in their host societies. To achieve this mission, the OKF has pursued three goals:

The first is to foster a Korean identity among diaspora Koreans, especially among the younger generations, by providing them with educational support.

The second is to enhance and expand economic and political cooperation between diaspora Koreans and their homeland.

The third is to build and integrate networks among the diaspora Koreans in particular countries, the homeland, and other areas of the world.

Soon after the establishment of the OKF in 1997, the Asian financial crisis struck. The South Korean government looked for help from diaspora Koreans, especially those from communities in wealthy Western countries. To attract investment from diaspora Koreans, it conferred virtual extraterritorial citizenship on them under the Act on the Immigration and Legal Status of Overseas Koreans in 1999. That Act gave diaspora Koreans the right to enter South Korea freely, conduct business, and own real estate.

The law initially excluded Koreans from China and countries of the former Soviet Union due to domestic concerns (labor market disturbances) and diplomatic considerations (opposition from the Chinese government, which asserted that Korean Chinese were citizens of the People’s Republic of China). Still, the law was soon revised to include all ethnic Koreans regardless of their country of residence [1]. Diaspora Koreans throughout the world responded to the call, confirming for South Korean policymakers and the public the importance of their diaspora population overseas. Building on the Overseas Chinese Business Convention, the OKF began hosting annual World Korean Business Conventions in 2002.

In 2010 the South Korean government took further action and revised the Nationality Law to recognize dual nationality—albeit limiting its scope and allowing eligibility only for certain people such as highly skilled foreigners, marriage migrants, Korean adoptees, and members of the Korean diaspora aged 65 or older. Allowing dual nationality can strengthen relationships between the diaspora Koreans and their ethnic homeland [2], [3]. This was an important step in light of the country’s long-cherished tradition of national ethnic homogeneity. In 2011, Korean nationals residing overseas were given voting rights. Debates in South Korea were heated on both policy measures—allowing dual nationality and granting voting rights—as has been the case in other countries implementing similar policies [4].

In addition to the legal changes, one of the most important projects of the OKF has been helping diaspora Koreans to network among themselves and with Koreans in their homeland. The OKF built online networks such as Korean Net and supported Korean diaspora media such as the Dongpo News and the Overseas Koreans Times.

One focal point of the OKF has been embracing and networking with the younger generations of the Korean diaspora and organizing homeland visits for them. Through these programs, younger overseas Koreans are invited to visit South Korea to learn the traditions, history, and language of their ancestral homeland, thus strengthening their sense of Korean identity. Participants include young diaspora Koreans not only from wealthy Western countries, but also from less developed countries such as China, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Uzbekistan. Participants in the programs are encouraged to network. The OKF has also run programs that bring Korean language teachers from all over the world to South Korea for training so that they can teach future generations in their regions.

The OKF has also been running special programs to reconnect Koreans adopted by families in Western Europe and North America with their ethnic homeland. Adopting families are generally wealthy, and so adoptees tend to receive a good education. And many renowned Korean adoptees have become influential in their countries of residence. The Ministry of Women and the Family has also organized such a reconnection service for ethnic Korean women who marry foreigners.

Diaspora engagement aims at generating economic gains through trade promotion and investment. These activities are carried out through the World Korean Business Convention and the Overseas Korean Traders Association. But the policy also focuses on re-nationalizing diaspora Koreans over the long run; strengthening ethnic and cultural identity in the Korean diaspora; making cultural, social, and political connections among diaspora Koreans and their ethnic homeland; and promoting networks among diaspora Koreans. South Korea is trying to build a new nation of expatriate Koreans, including all ethnic Koreans, wherever they may reside.

Costs and benefits of diaspora engagement

In the short term, diaspora engagement policies cost money. For example, extending government protection to a diaspora population that does not pay taxes or participate in military service is a challenging and sensitive issue [5]. Arranging for extraterritorial citizens to participate in national elections also costs money. But strengthening the Korean identity among diaspora Koreans all over the world will build loyalty to their ethnic homeland, and this is bound to bring numerous long-term benefits to the country.

Economic benefits

Although data are limited, it is clear that the diaspora engagement policy increases trade and investment. Korea has a long history of attention to its diaspora, encouraging support of the homeland both economically and politically. As long ago as 1910–1945, when Korea was under Japanese rule, diaspora Koreans in China, Russia, and the US eagerly supported the independence of their homeland by organizing anti-Japanese struggles. Later, during the early stages of South Korea’s economic development, they also supported the country through remittances and investments. In 1997, during the Asian financial crisis, diaspora Koreans in wealthy Western countries helped by sending money to Korea and buying Korean products.

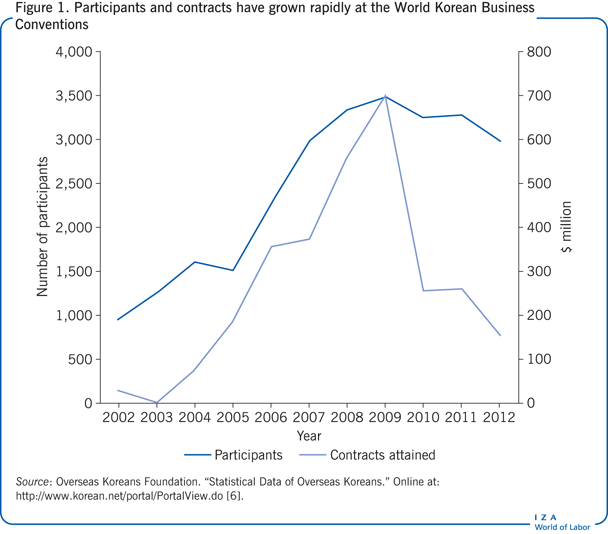

The annual World Korean Business Conventions foster economic cooperation between businesses in South Korea and those of the Korean diaspora. Since the first convention in 2002, the number of participants has tripled, and the number of business contracts attained at annual conventions has grown (Figure 1).

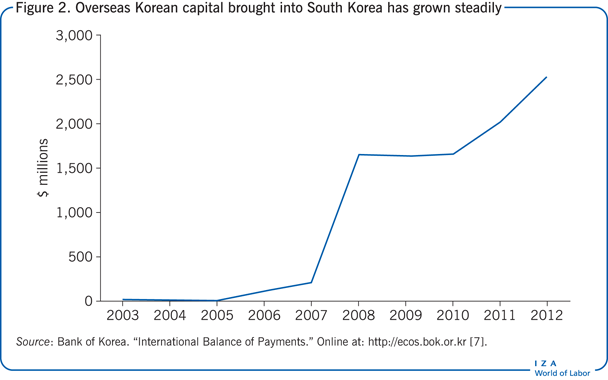

In addition, the capital brought in and invested in South Korea by overseas Koreans has grown steadily, except during 2008–2009, when growth escalated rapidly due to the global economic recession triggered by the subprime mortgage crisis in the US (Figure 2).

The existence of a diaspora normally increases trade between the immigrant sending and receiving countries. This trade often includes “nostalgia” or “taste” exports [8].

For the Korean diaspora, transnational migrant organizations like the Overseas Korean Trade Association (OKTA) have contributed greatly to the expansion of South Korea’s global exports. The association holds an annual Next Generation Trade Schools event to train young Koreans in trade and to strengthen their Korean identity. Recent programs have supported the government’s emphasis on tackling youth unemployment in South Korea. Each year, the association provides South Korean youth with hundreds of internship opportunities at diaspora-owned companies around the world. It also conducts local marketing promotions for Korean exporters, mobilizing local Korean firms.

Return migrants and brain gains

Brain drain was an issue in the 1960s and 1970s, when many Koreans left for better opportunities in the US and other Western countries. But during the administration of President Park Chung Hee (1961−1978), South Korea benefited from the return of a small number of migrants—especially scientists and engineers returning from the West. As many observers have noted, Korea and China have both benefited from the return migration of elite scientists and engineers [9]. Well-educated second- and third-generation Koreans from the West—including Korean adoptees, who tend to be particularly well educated—are now important assets of the country.

Since the early 1990s, the number of return migrants has been rising. The Korean diaspora is doubly beneficial as it, somewhat uniquely, provides both a cheap workforce (Chinese Koreans) and a highly skilled workforce (American Koreans). Korean return migrants from China have made a large contribution to the Korean labor market. Today, there are more than 300,000 Chinese Korean workers in South Korea, mostly manual laborers working in activities shunned by South Koreans. Return migrants from countries such as the US, with higher levels of education and English-language fluency, have also contributed to globalization of the country’s economy. Working for companies in South Korea, they contribute to the globalization and democratization of South Korea’s management culture and labor relations.

Allowing dual citizenship has also had some positive effects. Increasingly, older diaspora Koreans in Western Europe and North America are choosing to retire in their ethnic homeland, in part because it has become easier for them to receive their retirement pensions from their former countries of residence. For example, many Korean miners and nurses who lived in Germany are now retiring in South Korea.

The Ministry of Education, Science and Technology set up an online community, the Global Network of Korean Scientists and Engineers (www.kosen21.org), in 1999. The network taps the knowledge and skills of diaspora Koreans to develop Korean science, technology, and business. More than 80,000 ethnic Korean scientists and engineers, both in South Korea and overseas, participate in the network, exchanging more than 300 scientific and technological questions and answers each day. The site is also well used by the Korean business community. South Korea’s diaspora engagement policy thus helps Korean scientists, engineers, and businesspeople connect to each other online and offline, a powerful “brain gain.”

One reason for the government’s energetic pursuit of this engagement policy with the Korean diaspora is the political pressure from the diaspora itself. The Korean diaspora has a strong ethnic identity and, like the country, is relatively homogeneous. The homogeneity of the Korean diaspora distinguishes it from the Chinese or Indian diasporas, which are more divided along regional, linguistic, and religious lines.

Problems with the engagement policy

The diaspora engagement policy has had some problems. There has been some domestic opposition to granting citizenship rights and dual-citizenship rights to Koreans living abroad. Those opposed to the policy argue that citizenship should be restricted to those who fulfill their civic duties, such as paying taxes and serving in the military. The policy is also viewed as ethno-nationalistic, which is at odds with the multiculturalism policy that South Korea is pursuing to integrate its non-Korean residents into Korean society and the economy. Finally, the policy can lead to conflict with countries that have large numbers of ethnic Korean citizens. For example, China has affirmed the citizenship rights of the two million ethnic Koreans living in China.

Limitations and gaps

The lack of more systematic statistical data on—and the difficulty of quantifying—the direct economic, political, and cultural effects of Korea’s diaspora engagement policy is a challenge to analysis. And the long period required for the results of engaging a diaspora population to be manifested makes measuring the benefits and effects complex. Comparing South Korea with other countries pursuing similar engagement policies (such as China, India, Italy, and Mexico) could shed more light on the full benefits and costs of such policies.

Summary and policy advice

South Korea’s diaspora engagement policy was a response to a demographic crisis caused by a rapidly aging population, a falling fertility rate, continued emigration of the middle class, a rising number of non-Korean residents in the country, and a stagnating economy. The policy was intended to reinforce the country’s relationship with the seven million ethnic Koreans living overseas and to make it easy for them to contribute to the country’s growth.

The country’s policy of engaging with its diaspora has focused largely on two areas: strengthening ethnic identity among the Korean diaspora and building networks among members of the diaspora and between the diaspora and Koreans in their ethnic homeland.

To strengthen Korean identity among the diaspora, the South Korean government granted dual citizenship and voting rights to members of the Korean diaspora. It also organized education programs and homeland visit programs, especially for younger generations of the Korean diaspora. Reaching out to previously overlooked groups, such as Korean adoptees abroad and Korean women married to foreigners and living abroad, helped to re-nationalize many of them.

In an era of globalization, when people with multicultural backgrounds can contribute their creativity and unique perspectives, reaching out to the diaspora will bring long-term benefits to the country.

To strengthen the networks among the Korean diaspora and between them and their ethnic homeland, the OKF and other government organizations established and supported various organizations of businesspeople (World Korean Business Conventions, Overseas Korean Traders Association), scientists and engineers (Global Network of Korean Scientists and Engineers), and next-generation leaders. In particular, creating and supporting online newspapers and other online portals such as Korean Net has helped extend and integrate networks among the Korean diaspora. Such measures strengthened existing “imagined communities” of Koreans across the globe. The policy helped transform South Korea into an extraterritorial nation.

The policy of engaging members of the diaspora has brought substantial benefits to the South Korean economy—and more are expected over the long term. Small countries with substantial diaspora populations might achieve similar long-term gains from adopting policies to engage the diaspora. Such policies can be a smart response to the challenges of increasing globalization and transnationalism, even if they can be seen as fundamentally ethno-nationalistic.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. This work was supported by an Academy of Korean Studies grant funded by the Korean government (MEST) (AKS-2012-BAA-2101).

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Changzoo Song