Elevator pitch

Public sector jobs are created because governments opt to provide goods and services produced directly by public employees. Governments, however, may also choose to regulate the size of the public sector in order to stabilize targeted national employment levels. However, economic research suggests that these effects are uncertain and critically depend on how public wages are determined. Rigid public sector wages lead to perverse effects on private employment, while flexible public wages lead to a stabilizing effect. Public employment also has important productivity and redistributive effects.

Key findings

Pros

Expanding public sector employment can be an effective means of reducing unemployment in the short term, providing a stabilizing effect during recessions or in relatively disadvantaged regions.

Public sector employment can create demand in other sectors of the economy (e.g. private services).

Public sector employment supports equitable policies, such as encouraging employment of marginalized and/or disadvantaged groups.

Cons

Reducing short-term unemployment through expanding public sector employment can only occur when wages in the public sector are flexible according to productivity, rather than fixed.

The expansion of public sector jobs leads to “crowding out” of private sector employment; when wages are relatively unresponsive to productivity differences, this can even increase unemployment.

High public sector employment may lower overall productivity in an economy that is reallocating resources from the private to the public sector, or from higher to lower productive sectors.

Author's main message

Flexible public sector wages that adjust to local productivity, or that are highly pro-cyclical, are crucial for public employment policy to generate positive effects on total employment. Geographically homogeneous or time-rigid (a-cyclical) wages instead exacerbate unemployment. Policymakers should thus promote flexible, pro-cyclical public sector wages. However, given the institutional structure of wage setting, it may be difficult to ensure flexible public sector wages, in which case policymakers should be aware that a policy that increases public sector jobs can generate higher total unemployment.

Motivation

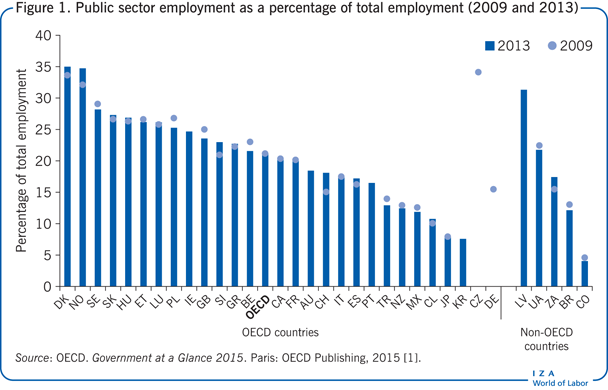

The share of public sector employment relative to total employment varies considerably across OECD countries (Figure 1), ranging from 8% in Korea and Japan, to 35% in Denmark. Governments also differ with respect to the amount of goods and services (e.g. in education or health care) they provide publicly to their citizens, and on how they provide those goods and services, with some governments providing them directly (through creating public sector jobs) or indirectly (by procuring the goods or services from the private sector market and redistributing them).

Most of the evidence shows that, when a government produces more public jobs it attracts workers that would otherwise have worked in the private sector, thus effectively “crowding out” the private sector. But is this always the case under any conditions, and to what extent?

Increasing public sector employment could feasibly crowd out more than 100% of private sector jobs (i.e. the creation of 100 new public sector jobs could result in the loss of more than 100 jobs in the private sector), thus generating unemployment. Alternatively, it could crowd out less than 100%, in which case it would have a positive impact on overall employment, and so could be used as a stabilization lever. Empirical and theoretical evidence shows that those effects depend on how wages in the public sector are set.

Discussion of pros and cons

Public sector employment and the economy

Governments can affect the private sector economy in a number of different ways. One important, and relatively less studied way, is the effect that public sector employment policies can have on private sector employment and on unemployment. Key questions in this respect, and which are addressed in this contribution, are the following: what is the effect of the size of public sector employment on private sector employment? What is the effect of public sector wage setting rules? Can public sector employment policies stabilize total unemployment? Can the public sector boost an overall productivity?

In answering these questions it will be seen that public sector employment also has other important effects. These effects may be the anticipated results of deliberate policies put in place by governments, or alternatively they could be unforeseen and undesired effects created by the combination of the policy and the institutional framework within which it is implemented. For example, through public sector employment policies governments can effectively increase the wages and employment level of disadvantaged groups, such as racial or ethnic minorities. This could be the result of intentionally targeting these groups and giving them priority for public sector employment—an example of which is the affirmative action program in the US—though it may also be the result of simple and clear wage setting and hiring rules that allow less space for discrimination.

Public sector employment can also be a source of redistribution of resources. When, for example, governments create more public sector jobs in regions that are relatively less advantaged, with higher unemployment and lower wages, they may implicitly divert resources from the more advantaged regions of the same economy in order to pay for those jobs. This arises when tax collection is relatively centralized and wages in the public sector are more homogeneous. Moreover, the creation of public sector jobs has important compositional effects, in terms of sectors of the economy. For example, when a hospital is built it will require a range of inputs from the private sector, in the form of building materials, desks, beds, and cleaning and catering services, thus creating demand in those sectors.

Finally, the public sector is more competitive with some sectors of the economy (typically the tradable sector—whose output (goods or services) is traded internationally, or could be traded internationally given a plausible variation in relative prices—which is also generally more productive) and more complementary with others (typically the non-tradable sectors). This implies a reallocation of resources that can lead to a negative effect on overall productivity i.e. if the public sector creates demand, especially for less productive sectors such as services, then it can lower overall productivity.

Public employment, private employment, and unemployment

When considering the effect of the size of public sector employment on private sector employment, most recent research has found that higher levels of public sector employment lead to a reduction in private sector employment. The reason for this is that the public sector competes for workers in the labor market with the private sector, and this competition leads to the private sector losing workers to the public sector. There is evidence for this, both at the aggregate levels of countries, and at more disaggregated levels of regions and local markets.

At the aggregate level, a panel data analysis of OECD countries found that if a government hires one additional public sector employee it has a negative effect on private sector employment, reducing it by one and a half employees [2]. However, this study also reports that a proportion of the displaced workers from the private sector become inactive (i.e. they drop out of the labor market) while another part becomes unemployed. Therefore, the overall effect on unemployment is smaller, but nevertheless still positive, in that it increases unemployment. Similar findings are provided by another study looking at Swedish aggregate time-series data from 1964 to 1990 [3]. However, most interestingly, another study using OECD data has recently found that the correlation between private and public sector employment is not always negative and, in some countries, is actually positive [4]. The authors of this study point to the fact that the conditions of the labor market itself and how the private and public sectors compete is fundamental in determining the sign of this correlation.

At the level of local markets, one study analyzing British data found that an increase in public sector employment was not associated with any significant change in overall private sector employment [5]. However, when looking at the compositional effects on private sector employment the study finds significant effects, in that the non-tradable sector (i.e. construction and services) benefitted from the creation of public sector jobs, by adding 0.5 jobs for each public sector job created, while the tradable sector (i.e. manufacturing) suffered by losing 0.4 jobs for each public sector job created. This shows that the public sector competes more with some sectors of the economy (i.e. the tradable sector) while being more complementary with others. One possible explanation for this complementarity is that, at the local level, the government creates additional demand for those sectors.

This study also importantly indicates one possible channel through which public sector employment can affect the overall productivity of the economy. The tradable sector is by definition the most open to the international market and, as such, needs to be the most competitive and highly productive, otherwise business enterprises would have insufficient margin for profits. The non-tradable sector, especially some sub-sectors in services, may face lower competition, in which case private firms in this sector may still have profit margins, with a relatively lower level of productivity than firms in the tradable sector. By changing the composition of private sector employment in favor of the relatively lower productive sector (non-tradable sector), the public sector can effectively make the entire economy less efficient and less productive.

Overall, it is not obvious how the size of the public sector directly affects the private sector. Other factors also need to be taken into account. Indeed, the wage setting rules that the public sector follows are the most important determinant of the relationship between the two sectors.

The importance of wages

The evidence for the crowding-out effect of public sector employment on private sector employment supports the hypothesis that the public sector competes with the private sector in the labor market for hiring workers. While the competition may involve several aspects of a job, such as job security, amenities, pensions, and health plans, the most important aspect of a job, for most workers, is the salary that accompanies it. How governments set wages to compete for workers is thus a very important factor, which can lead to a number of different scenarios.

One study shows that the crowding-out effect, and its relationship with unemployment, can be either positive or negative depending on how “rigidly” public sector wages are determined by governments [6]. Economic theory suggests that the primary factor determining the wage paid to a worker is productivity. Profit-maximizing private firms have an incentive to pay more to workers employed in jobs that produce more, and less to workers in jobs that produce less. In contrast, the objective of the public sector is not to maximize profit. As such, the wage setting within the public sector may be less tied to productivity than in the private sector. As the public sector competes with the private sector for workers, a necessary condition of hiring workers is that they are paid at least as much (not considering other benefits) as they would expect to be paid in the private sector. If this was not the case, there would be little incentive to accept a job in the public sector.

However, governments may have incentives to create simple and clear rules that minimize the differentiation of wages among workers with similar jobs. Indeed a large body of empirical research has shown that public sector wages are both higher and more homogeneous than private sector wages.

Greater homogeneity can be a positive or negative result of public wage setting rules. For example, one study shows that women in the public sector are paid wages that are closer to those of men doing similar jobs [7]. Another study shows a similar result for black people in the US [8]. An incentive for creating simple and clear rules for paying workers with similar jobs similar wages is therefore a reduction in discrimination against minority groups. This also has spillover effects on the economy in general, making these groups more competitive. However, simple and clear rules can often create rigidities that have negative effects.

Wage rigidity

There are at least two dimensions in which wage rigidity can prove to be detrimental: a spatial dimension, which considers different regions or cities, and a time dimension, which looks at different periods in time. A substantial body of evidence that looks at the regional distribution of wages shows that, particularly in Western European countries, public sector wages are geographically more uniform than private sector wages. For instance, one study shows that public sector employees in southern Italy are paid the same wages as their counterparts in the north, while private sector employees, due to the fact that productivity in the south is generally lower, face a wage gap of about 10% [9]. Similar evidence of public sector wages being more regionally homogeneous than private sector wages is presented in other studies for the UK, Germany, and France.

Moreover, a wider gap between public and private sector wages seems to coincide with higher regional unemployment. Furthermore, private sector wages decline with rising regional unemployment, while public sector wages do not [10]. This suggests that while public sector wages are more similar across regions, private sector wages decrease with unemployment, and their wage gap becomes wider. Other studies do not include unemployment specifically among the possible variables related with public sector wages, or the public/private sector wage gap. However, in the case of Germany, for example, it has been found that the public/private sector wage gap remains substantially wider for eastern regions than for western, where unemployment is much higher.

Wages have also been found to be more rigid in the public sector than in the private sector over time. One study shows that the public sector pays its employees better, i.e. there is a positive wage gap in their favor compared to private sector employees, and, most importantly, the wage gap is counter-cyclical, that is, it is larger during downturns of the economy [11]. The reason, as the authors show, is that public sector wages do not adjust as rapidly as private sector wages to fluctuations in productivity, which leads to higher employment volatility in private firms during the business cycle.

Crowding out and the destabilizing role of public sector employment

Most of the theoretical models that address the effect of public sector employment on private sector employment and unemployment rely on the pioneering work of the Nobel prize-winning economist Christopher Pissarides, and on some application of his “theory of search” in labor markets. According to this theoretical background, crowding out occurs when the public sector competes with the private sector for workers, which creates more tension in the bargaining process in favor of workers. A larger public sector leads to more competition and higher wages in the private sector, which translates into lower private sector employment.

As evidenced by a number of empirical studies referred to earlier in this contribution, the crowding out generated by the competition of the public sector can be more than 100%. This means that the number of jobs lost by the private sector can be more than the number of jobs created by the public sector. This occurs when wages in the public sector are so attractive and the probability of finding a job is sufficiently high, that unemployed workers prefer to wait longer to find a public sector job. Moreover, when wages in the public sector show more rigidity with respect to fluctuations in productivity, the crowding-out effect becomes stronger when productivity is lower, which in turn amplifies the effect of real business cycles on unemployment. The amplification, or destabilizing, role of the public sector is stronger the higher the wage gap is in favor of the public sector and the larger its size.

A similar destabilizing role can also be generated when the public sector pays homogeneous wages across regions that have different productivity levels. One study finds that about half of the unemployment gap between the south and the north of Italy can be explained by the role of the public sector [9]. Were public sector wages in line with those of the private sector, that is, paid according to local productivity, the unemployment gap would be half of what it has been historically. The same study shows that the rigidity of wage setting in the public sector clearly explains the differences in performance of the labor markets in the south and the north following the great recession of 2007/2008, with the southern market losing many more jobs that the northern market.

The potential stabilizing role of public employment and taxes

More recently, one study looking at metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) in the US, finds that high public sector wages are associated with an increased sensitivity of MSAs to aggregate shocks, while a high rate of public sector employment is associated with a decreased sensitivity [12]. This holds true for the private sector and the economy as a whole. The study also finds that high public sector wages are associated with high private sector wages, and that a high rate of public sector employment is associated with lower private sector wages. This evidence mostly confirms previous findings, but also sheds more light on the complex effects of the public sector on the general economy. In particular, the authors stress that while higher public sector wages are always associated with crowding out and higher employment volatility in the private sector, the size of the public sector relative to total employment, at least in the US case, is associated with lower volatility and lower wages in the private sector.

The main source of competition between the private and public sectors is the relative wage rate. The rules adopted by the public sector to determine the compensation of public employees are crucial in determining the overall effects of public employment. When the wage gap in favor of public employees is relatively small and wages react to productivity quickly enough, the public sector generates only “mild” competition and the crowding out effects are small.

The study also takes into account an equilibrium, or balancing, effect between the private and public sectors, as a result of the resources collected from the private sector directly supporting the additional expenses of the public sector [12]. A large public sector drains more resources, in the form of taxes, from private sector households which, as a result, have less disposable income. This leads households to supply more labor and to accept a lower wage for a job, which in turn leads to reduced volatility and lower wages, as well as a positive effect of public sector employment on the private sector. However, higher wage gaps between public and private sectors, and rigid wages in particular, can reverse the effect of a bigger public sector on private sector employment.

It is important to note that this “equilibrium effect” holds true only for as long as the resources collected through taxes are collected predominantly within the same market as where the effect is measured. This is the case for the US, for instance, where most of the public sector employment is state or city employment, and the corresponding taxes are collected within those jurisdictions. For other countries, especially in Europe, taxes are generally collected at the national level, even when public employees are unevenly distributed across the country. In this case, in addition to higher public employment, the result can be a redistribution of resources [13], which may then lead to a different type of equilibrium that includes higher wages for the private sector. For example, one study shows that higher local public sector employment leads to higher wages in the UK and, at the same time, to a higher demand for goods and services produced by the non-tradable sector [5]. Another study shows that the uniform tax system in Italy exacerbates the crowding-out effects of public employment in the weaker regions of Italy.

Limitations and gaps

Although it is clear that there are strong relationships between public and private sector employment, further research is required for a better understanding of the extent to which public sector employment directly affects the private sector.

First, while it is clear that the relationship between the public and private sector is not one- but two-way, theoretical models do not currently take this into account. Consequently, the feedback of the private sector to the public sector, which is implicit to the correlations that are apparent in the data, is not incorporated into the analysis. Models that include this feedback would provide more accurate predictions and, in turn, would allow for more appropriate policy responses.

Second, while there has been some research to disentangle the effects of public sector employment on private sector employment, both empirical and theoretical research on this is still quite scarce. More and better knowledge, for more countries, is required. Research also needs to take into consideration the effects of changing the size or wages of public sector employment over longer periods of time—this would shed more light on the efficiency and productivity effects of those policies. To this extent, it would be interesting to access and utilize data on different sectors (such as services and manufacturing) within the public sector itself.

A further aspect that has not been explored in the literature so far is if, and how, the public sector affects the institutional structure of wage bargaining in the private sector—unionization in particular.

Also less studied are the possibly positive effects of public sector employment on the employment gender gap, the gender wage gap, and more generally on female labor relationships and benefits. Public employees, as seen earlier, are less likely to be discriminated against. This can be reflected in the wage paid, but also through a range of other benefits that workers are entitled to, either by law or through employment contracts. One such set of benefits is parental leave packages paid to new parents. While these packages are often directed to both men and women, women are, in most countries, those who benefit the most from them. This may be one of the reasons why the public sector employs disproportionately more women than the private sector. A high level of public sector employment then can also imply higher female labor participation, together with a series of other potentially positive outcomes, such as, for example, higher fertility, as a result of better employee benefits.

Finally, this contribution has presented evidence on the relationships between public and private employment and unemployment for OECD countries. Theoretical models can help interpret those relationships and derive predictions for public policies. However, the public sector is also a very important component in non-OECD countries, including developing and transition economies. Unfortunately, data availability represents a considerable constraint in analyzing the effect of public employment in these countries. With more and better data on developing and transition economies it will be necessary and useful to verify whether the same empirical relationships appear as in OECD countries.

Summary and policy advice

Governments around the world differ significantly in terms of the type and number of goods and services they choose to provide to their citizens. They also differ in terms of how they choose to provide them—it could be via direct public sector provision or through private sector procurement processes, and they could be paid for in full, or in part, through taxes. The choice of how to produce and deliver these goods and services implies different levels of public employment, even if the overall public expenditure for goods and services is similar. This difference has important implications for the functioning of the private sector and for the overall performance of a country.

Economic research has shown that public sector employment can have important and long-lasting effects on private sector employment and overall unemployment. In particular, the public sector competes with the private sector for workers, and this competition can increase the tension in the wage bargaining process and, ultimately, the wages of workers in the private sector. This tension generates a crowding-out effect that brings workers from the private into the public sector. However, the size of this effect, and the eventual effect on unemployment, crucially depends on the wage setting rules within the public sector.

So far, the available research suggests that when public wages are relatively high and unresponsive to productivity, higher public employment negatively affects private employment and increases unemployment. This leads to a destabilizing effect of the size of public employment on unemployment across business cycles. However, when public wages are responsive to productivity and adjust similarly to private wages, then the size of public employment acts as an automatic stabilizer, that is, it reduces the fluctuations of unemployment over the business cycle.

It is also clear that the role of taxes is not neutral. When the focus is shifted to the regional effects of public sector employment, it can be seen that a uniform distribution of tax collection may generate implicit subsidies from regions with lower shares of public employment over total employment, to regions with higher public employment shares. However, these effects are countered by an increase in labor demand, which in turn may lead to an increase in private sector employment, at least in some sectors of the economy (e.g. services). When, instead, taxes are more locally concentrated and public wages are flexible enough, the stabilizing role of public employment is increased by a local equilibrium effect that lowers wages and increases private sector employment. This is empirically relevant, at least for the US economy.

Given these findings, policies that increase public sector employment should be accompanied by wage setting policies that allow wages to be as flexible as possible relative to productivity, both in time and across regions or cities. While there are benefits to having a relatively large public employment sector, the size of the public sector can be detrimental to the private sector of the economy. This, however, is true only when private sector wages are relatively higher than public sector wages (or the benefits that come from public sector employment are more advantageous), and relatively inflexible.

Another important caveat of public sector employment is how well the economy is performing. Public sector employment can generate lower productivity by diverting resources from more to less productive sectors of the private sector economy, or from the private sector to the public sector economy, which is generally less productive. Therefore, when governments choose between providing goods and services directly (by creating public employment) or indirectly (by relying on private sector procurement), the potential effects should be carefully evaluated and considered in terms of the wider economic implications.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [12].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Vincenzo Caponi