Elevator pitch

Higher labor costs (higher wage rates and employee benefits) make workers better off, but they can reduce companies’ profits, the number of jobs, and the hours each person works. The minimum wage, overtime pay, payroll taxes, and hiring subsidies are just a few of the policies that affect labor costs. Policies that increase labor costs can substantially affect both employment and hours, in individual companies as well as in the overall economy.

Key findings

Pros

Cutting labor costs induces companies to employ more workers.

Increasing the minimum wage that employers must pay their workers prevents employers from exploiting workers who have few alternatives.

Increasing the minimum wage that employers must pay their workers increases earnings among low-wage workers who retain their jobs.

Increasing the penalty that employers pay for overtime work prevents employers from imposing long hours on individual employees.

Increasing the penalty that employers pay for overtime work may encourage new job creation that can reduce unemployment.

Cons

Any cut in the supply of labor to a market will raise wages—and raise employers’ costs.

Increasing the minimum wage that employers must pay reduces total hours worked—total jobs times hours per job—but with small impacts if minimum wage levels are low compared to average wages.

Increasing the minimum wage that employers must pay their workers has the biggest negative effect on the unskilled and minorities as well as young and older workers.

Increasing the penalty that employers pay for overtime work reduces total hours worked.

Increasing the penalty that employers pay for overtime work reduces GDP.

Author's main message

Higher labor costs reduce employment and/or the hours worked by individual employees. Laws that raise labor costs can either increase total employment or increase hours per worker, but they cannot do both. They lower the total amount of work performed in the market—the total number of person-hours (hours per worker multiplied by the number working). This loss must be traded off against the benefits that higher costs might provide to specific groups of workers.

Motivation

Every employer is concerned about labor costs—that is, higher wage rates and employee benefits. An attractive package is essential to induce people to apply for jobs and to work hard, but it will also subtract from the employer's revenue and thus reduce profits. In any economy, policymakers confront a trade-off between imposing higher wage costs—for example, by introducing or raising a minimum wage—that benefit workers but reduce profits. Knowing how employers react to higher labor costs is essential for understanding how jobs are created and for predicting the economic impacts of labor legislation.

Discussion of pros and cons

The central question here is whether an employer's reaction to higher labor costs differs from a consumer's reaction to increased shirt prices? In general they should not be different: in both cases the focus is on how somebody's demand for something reacts to an increase in its price. With shirts, it is expected that higher prices will lead customers to buy fewer shirts and to wear the shirts that they do buy for longer. With workers, higher costs will lead employers to use fewer employees and to “use” them more productively. In a few labor markets where one employer dominates or is the sole employer, the employer might respond differently; but such markets are rare, increasingly so as labor forces grow and transportation improves.

The only important question is by how much employment falls when labor costs increase. It is not a question of whether it will fall, but rather one of how big the reduction will be. It is a more important question in the case of workers than of shirts because about 60% of all income in a modern economy is generated by employment.

Adjusting employment when capital cannot be adjusted

When labor costs increase, an employer's immediate options are to do nothing and absorb the extra cost, or to reduce the amount of labor employed. It takes time to alter investments in machinery, buildings, and technology, which might allow a more efficient operation. On the other hand, changing workers’ hours, or the number of workers, is quicker and easier. So an employer's first decision when labor costs rise is whether to do nothing or to reduce employment and/or hours; and, if the latter, by how much [1].

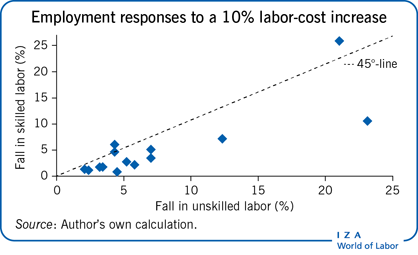

One set of evidence on this question comes from large-scale studies examining how employment changes in industries where hourly wages increase more rapidly than in other industries in which all other conditions are essentially similar [1]. These studies, conducted for many different countries and different industries, yield—unsurprisingly—a wide variety of conclusions. Nonetheless, a reasonable consensus from this vast body of research is that higher hourly wages induce employers to cut employment and hours worked. The best inference from these studies is that a 10% increase in labor costs will lead to a 3% decrease in the number of employees (or to a 3% reduction in the hours they work, or to some combination of both). This is sometimes referred to as the “3 for 10” rule. Taking the responses of unskilled and skilled employment to a 10% decrease in labor costs, the Illustration on p. 1 suggests responses that are on average very close to the 3 for 10 rule.

Much (although far from all) of this research ignores the fact that employers make wage and employment decisions at the same time. This raises the “chicken and egg” question of whether it is the rise in labor costs that causes employment to fall, or whether an increase in the demand for workers causes employers to raise wage rates. To get at the causality question, some studies focus on specific examples of the impact of shocks that alter the number of workers available to employers or that consider externally imposed changes in labor costs. Studies examine how the intifada in the Israeli-occupied territories altered wages and employment [2]; how sharp decreases in payroll taxes in Sweden increased manufacturers’ demand for labor there [3]; and how the withdrawal of able-bodied men from the American civilian workforce during World War II altered women's employment and wages [4]. Here too the evidence is varied. But, in sum, higher hourly wage costs do lead employers to use fewer workers.

How rapidly do employers adjust to an increase in labor costs?

Employers do not react instantly when labor costs increase. It takes a while before they believe that the increase is not just a temporary aberration. They know that it will take time to find new workers if and when labor costs drop again. Furthermore, because of government restrictions on layoffs, and because reducing their workforce by waiting for employees to quit is limited by how many actually do quit, and when, employer responses cannot be instantaneous. Despite these impediments, the evidence is very clear that things move fairly quickly. In the US at least half of the cuts in employment demand when labor costs increase occur in the first six months, while in continental Europe the adjustment is slower, but not greatly so [1].

Increases and decreases in employment need not proceed at the same speed. That depends upon the costs of hiring and firing—so called “adjustment costs”—and on how they change with the number of workers hired or fired over a period of time. If the costs per worker rise more rapidly with the number of hires/fires, it pays employers to stretch out the adjustment. Evidence suggests that hiring costs are far less than firing costs, especially in Western European economies, consistent with the idea that adjusting employment is asymmetric: hiring proceeds more rapidly than firing in response to a shock to the labor market [5].

How fast does a market adjust to a shock?

While labor demand adjusts fairly rapidly, shocks to labor markets generate adjustments in people's residences and in structures that house offices, shops, and factories, and these may take substantial time. Evidence for shocks to the US labor market when statutory minimum wages are increased suggests that it may be three years after a shock before most of the adjustment is complete [6].

Adjusting employment when capital investment can be changed

A rise in wage costs per worker or per hour makes using more capital an attractive option for employers. If time allows, the capital investment option is increasingly taken up, so that the employer substitutes capital for labor. This takes time because it is more challenging to install new machinery or build new facilities that allow the company to operate more efficiently. This means that the 3 for 10 “best guess” at the initial response of employment levels to labor costs underestimates the eventual response. Indeed, the evidence suggests that the eventual response of employment to an increase in labor costs is much bigger [1]. A good estimate is that each 10% rise in labor costs eventually leads to a 10% drop in employment and/or hours—a 10 for 10 response.

Another way for an employer to change the amount of capital invested, as well as to reduce their need for labor when labor costs change, is to close an existing establishment. Going still further, businesses may even shut down all their operations if labor costs increase sufficiently to make the business unprofitable for the foreseeable future. The question is whether the impact on total employment of a given increase in labor costs as the result of businesses closing is the same as the impact due to business cutbacks. On the other hand—looking at what happens when labor costs fall—the question is whether jobs generated through the birth of new businesses in response to cheaper labor are in the same proportion as jobs created through expansions in existing businesses.

There is relatively little specific evidence on the impact of labor costs on job creation or destruction due to establishments or companies opening or closing. The few studies that exist indicate that responses to changes in labor cost working through these more dramatic channels do not, on average, differ much from those resulting from plant expansions or contractions [1].

Not all workers are affected the same way by increased labor costs

The 3 for 10 immediate and 10 for 10 eventual responses to increased labor costs are averages, but there is no such thing as an “average worker.” Some workers have more experience, better skills, and/or more education. Male workers differ from female workers, racial/ethnic majority workers from racial/ethnic minority workers, and so on. The extent to which employers’ demand for workers changes when labor cost increases differs across all these distinctions.

In one way or another, these intergroup differences distinguish the skills that workers in different groups possess. Thus, a good way to generalize about differences in how employers respond to increases in the costs of labor of various workers is to consider how skilled the workers are. Evidence demonstrates that the responses of employment levels to a particular labor–cost increase are smaller the more skilled the workers are [1]. For example, a 10% increase in labor costs leads employers to cut the employment of teenage and young adult workers by more than that of mature workers. When the labor costs of less-educated workers increase, their employment is reduced by more than that of university graduates for the same increase.

Evidence on this issue is found in many studies covering different countries, skill levels, and periods of time. The Illustration on p. 1 shows the results from a number of these studies. For each, the fall in skilled employment is plotted against the fall in unskilled employment when labor costs increase by 10%. The diagonal line shows points where the implied changes in skilled and unskilled employment are equal. In all but two of these diverse examples, the change in skilled employment is less than that in unskilled employment.

Fire employees or cut hours per worker?

Whenever there is an increase in the cost of an hour of work—the worker's wage rate—the employer faces a choice: fire employees, cut hours worked, or some combination of both. The choice matters to society: most people would rather see all workers lose four hours per week than see 10% of them lose their jobs while the remaining 90% keep their jobs with no changes in weekly work hours.

There is another important consideration—fixed labor costs, which do not vary if hours per worker are cut. For example, if the employer is responsible, as in the US, for providing medical insurance to his/her workers, those costs will not be reduced when hours per worker are cut with the number employed unchanged. Similarly, if employers are taxed on some small amount of a worker's annual pay, as they are in the US by the tax that finances unemployment insurance, labor costs are not reduced if hours per worker are cut. Thus, the employer's response to an increase in labor costs is not indifferent to its type [7].

Increases in the hourly wage rate and increases in these fixed costs reduce both employment and hours. But a rise in the fixed costs of labor increases the cost of an extra worker relative to that of an extra hour per worker. Because of that, imposing a per-worker tax causes employers to hire fewer workers and to extend the hours of existing workers [7].

While the choice between cutting workers or hours per worker depends on the cost of each, the most important consideration is the total product of workers and hours (i.e. the total amount of labor used) that is generated by any combination of fixed and per-hour labor costs. After all, it is the total number of worker-hours across the economy that determines how much is produced—the GDP. From the perspective of the economy as a whole the evidence on this is clear: an increase in wage rates reduces employment and total hours, and an increase in the fixed costs of a worker reduces the total number of hours worked. Any increase in labor costs, regardless of its source, will lead employers to cut the total number of hours that they seek to use.

Some important policy examples

Minimum wages

Many countries impose minimum-wage requirements on most employers. In the US in 2020 there was a national minimum of $7.25 per hour, which is around 22% of the average hourly wage (and an even lower percentage of average labor costs). A majority of US states (and many cities) set minimum wages above that (as high as $15 per hour). In Canada, provinces set separate minimum wages; while the UK, France, and Germany have national minima. In the US the purpose of these minima was stated when the Fair Labor Standards Act was first enacted in 1938: “To take labor out of competition”—that is, to prevent companies from exploiting workers in their search for lower labor costs and higher profits.

When effectively enforced, a minimum wage increases labor costs. It does this, though, for those workers whose wage would otherwise be below the minimum. The demand for a professor who can earn $50 per hour will not be affected by a $7.25 per hour minimum wage; it is the demand for a day-laborer who might otherwise earn only $7.00 that will be affected. The impact of a higher minimum wage on employment therefore depends on two things: how many workers might otherwise earn less than the minimum; and how much it will reduce employment among those workers.

The second effect seems clear: the demand for low-wage workers—who tend to be low-skilled workers—responds more sharply (negatively) than average when labor costs are increased, as has already been noted.

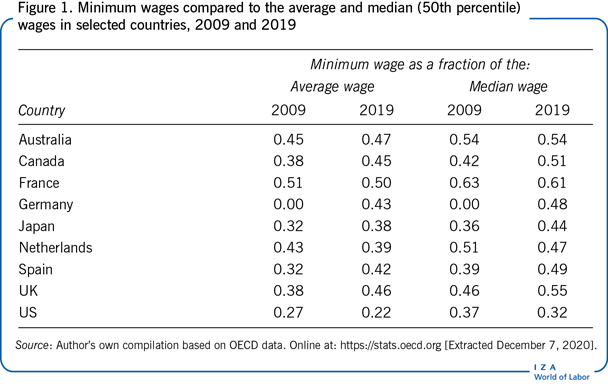

Figure 1 shows that there are substantial differences in the relative importance of statutory minimum wages across major economies: the US has a low national statutory minimum wage, while France has a very high minimum (0.50 of the average wage). In most of the nine countries listed in Figure 1 the ratio has risen or at least remained constant over the past decade. The figure also implicitly makes the important point that what matters is the fraction of workers whose wages are sufficiently low that an increase in the statutory minimum might affect the demand for their services.

Research on the effects of the minimum wage has occupied economists for over half a century, probably to a much greater degree than the policy's importance warrants. Despite all the research, the conclusions remain very controversial, in part because they deal with a policy issue that is universally contentious. A fair reading of the evidence suggests that a higher minimum wage has small negative effects on employment, and that these effects increase the more the minimum is raised relative to the average wage [8]. Also, however, raising the minimum wage does result in higher earnings for those low-wage workers who remain employed despite their higher cost.

Minimum wages in a former communist economy

Between 2000 and 2002 Hungary raised its minimum wage from below 40% of the median wage to nearly 60%, a huge and rapid increase by international standards. This resulted in a drop of employment of about 10% in firms affected by the increase. Three-quarters of the cost of the wage increase was paid for by customers through higher product prices, one-quarter by employers’ lower profits [9].

Overtime pay

A second policy example is overtime pay. In effect, overtime pay is a penalty paid by the employer for hours worked by an employee beyond a statutorily specified maximum. In some countries employers must pay overtime rates for each hour a worker puts in per week beyond a standard number of hours (40 in many countries, including the US, Japan, and Korea). The extra amount paid may be 50%, as in the US, or 25% as in Japan and many other countries. In some countries the overtime rate starts low but rises after a few hours are worked; for example, in Korea the additional amount paid is 25% for the first four overtime hours worked per week rising to 50% thereafter. In many countries there are statutory weekly and/or annual maxima on overtime work; in some the overtime penalty applies on a daily rather than a weekly basis.

All these policies have two purposes: to “spread” work by providing employers with incentives to employ more workers, each of whom is working a shorter workweek; and to protect workers from being forced to work very long hours at undesirable times. The evidence makes it very clear that these laws are effective in inducing employers to introduce shorter workweeks, an example being Japan in the 1990s [10], and to avoid long workdays [11]. Although it is not clear how much they do spread work (i.e. cause employers to employ more workers than they otherwise would), they do increase the number of employees relative to the number of hours each worker puts in. It is clear, though, that they reduce the total number of hours worked (hours times number of workers) by raising the cost of labor [8].

Penalties for unusual timing

Employers’ demand for labor has a temporal dimension in addition to its quantitative dimensions: when people work matters to both employers and to workers. Many employers earn higher profits by operating their businesses at night and/or on weekends, creating a demand for workers at what might be unusual times. Their desires for increased profits conflict, though, with workers’ apparent preferences against working when most other workers are enjoying leisure, including on weekends and at night. Thus, not surprisingly, in most modern economies such work is performed disproportionately by less-skilled, minority, and immigrant workers, for whom these undesirable work times are often the best they can obtain.

In many countries, employers who remain open on weekends or at night must pay legislated penalty rates to their employees, penalties that are independent of the amount of time worked per week (which is covered by the overtime laws discussed above). For example, in Portugal, work during weekday nights is penalized at a 25% rate; work on weekend days can be penalized at up to a 100% rate, while on weekend nights the penalties can reach 150% of the usual wage rate. In some other countries, such as the US, no such legislated penalties exist.

The extra cost to employers of operating at night or on weekends that these penalties impose does reduce such work—they shift some of the demand for labor at unusual times to more standard work times [12]. While research on this issue is still sparse, the evidence thus far suggests that employers’ scheduling of work time is quite responsive to higher penalties. Raising the cost of work scheduled at times that workers find undesirable will substantially reduce the amount of such work that is undertaken.

Payroll taxes and the demand for skill

In many countries, the payroll tax on an employer is at least partly capped: it does not apply or is reduced on earnings above some legislated amount. In the US, for example, the tax on employers that finances public retirement and medical benefits in 2021 is 7.65% on annual earnings below $142,800 per year, but only 1.45% on additional earnings exceeding that level. The much lower tax that finances the administration of unemployment insurance is capped at earnings of only $7,000 per year.

The level of these caps affects the relative demand for workers with different skills. At the same percentage tax rate, reducing the tax cap disproportionately raises employers’ costs on low-skilled workers. Employers in many industries readily substitute skilled for unskilled workers when their relative costs vary, so that reducing the cap will reduce employers’ relative demand for less-skilled workers by raising their relative cost. Policymakers thus need to consider how any change in payroll tax rates, or in the ceilings on the amount that is taxable, will alter the employment of workers who differ by skill level, for example, by experience in the labor market.

Hiring credits

Many countries attempt to subsidize employment by offering employers credits for adding workers to their payrolls. These are often used in recessions to stimulate employment recovery; and in many cases they are geared toward lower-skilled workers. Do they work—do they produce increases in employment?

France offered such a credit, geared toward low-wage workers and small firms (fewer than ten workers). The evidence suggests that smaller firms added total hours compared to firms just slightly larger which did not qualify for the subsidy. This occurred through an increase in hiring and also through an increase in hours per worker [13].

Limitations and gaps

The question posed in the title of this article is one of the broadest in the “World of Labor.” The reaction of the demand for workers and hours to changes in labor costs underlies both an employer's private considerations and a wide variety of questions of public policy in every economy. Given its breadth, one cannot expect to find specific answers to specific questions. Research can, and has, however, answered such general questions as:

How much does employment fall on average when labor costs rise by some amount?

How does the answer to this question change with differing worker characteristics, such as skill levels?

How do the number of workers employed and hours per worker change as various types of labor costs change?

Other, specific questions cannot be answered, such as:

How would the number of workers in Bulgaria change if the Bulgarian government imposed a 10% payroll tax on the employment of all workers?

How would the number of workers in Slovakia change if the Slovakian government imposed a 10% payroll tax on the employment of skilled workers?

How many fewer hours per week would Vietnamese employers use their workers for if they were required to pay a 100% overtime rate on hours per worker beyond 40?

These particular examples are of narrow interest, but questions like them apply in each country and for each type of worker. The evidence presented here suggests general guidelines that allow policymakers a general view about the direction, and in some cases the sizes, of the impacts of proposed increases in labor costs on outcomes such as employment and hours. What it does not do is allow answering specific questions. To arrive at detailed answers to policy and other questions in specific (national, worker-type) instances, targeted research is required that addresses the particular example.

Summary and policy advice

Higher labor costs unaccompanied by technology changes that increase productivity reduce employers’ willingness to hire workers and reduce the total amount of work done in any economy. This fact, which is well established by the evidence, means that any attempt to make workers better off by raising their wages or giving them wage premia for longer hours of work will reduce the total amount of labor that employers will use. With less labor, less will be produced. How much employment will drop on average for a given increase in labor costs, and how the magnitudes of these declines will differ across groups of workers with different characteristics are known. So too is the fact that changes in labor costs that raise the cost of an extra hour of work while leaving unchanged the cost of an extra worker will induce employers to substitute workers for hours.

Policymakers need to be aware that negative consequences are possible when increasing minimum wages or imposing other measures that increase labor costs. Some people will benefit, but each increase will reduce the number of jobs and/or the total amount of work available in the economy.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates “Figure 1,” adds new information on adjustments to economic shocks, minimum wages in Hungary, and hiring credits, and includes new “Key references” [3], [5], [6], [8], [9], [10], [11], [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Daniel S. Hamermesh

Cutting payroll taxes in Sweden

Source: Egebark, J., and N. Kaunitz. “Payroll taxes and youth labor demand.” Labour Economics 55:1 (2018): 163–177.

Labor cost and demand in the US during World War II

Source: Acemoglu, D., D. Autor, and D. Lyle. “Women, war and wages: The effect of female labor supply on the wage structure at mid-century.” Journal of Political Economy 112:3 (2004): 497–551.

Imposing the 40-hour workweek in Japan in the 1990s

Source: Kawaguchi, D., H. Naito, and I. Yokoyama. “Assessing the effects of reducing standard hours.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 43:1 (2017): 59–76.