Elevator pitch

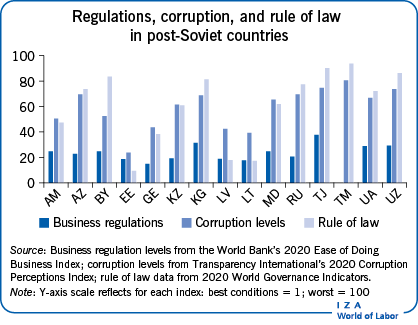

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the differing impact of institutions on entrepreneurship development is undeniable. Several post-Soviet countries benefitted from early international integration by joining the EU, adopting the euro, and becoming OECD members. This process enabled entrepreneurship to develop within institutional contexts where democratic and free market principles were strengthened. In general, however, post-Soviet economies continue to be characterized by higher levels of corruption, complex business regulations, weak rule of law, uncertain property rights and often, lack of political will for institutional change.

Key findings

Pros

International integration such as EU membership enables member countries to enact the reforms needed for productive entrepreneurship.

IT and tech sector business development offers new opportunities for increasing entrepreneurship in post-Soviet countries.

Increasing numbers of productive entrepreneurs can support sustained institutional reform.

The post-Soviet country diaspora has substantial potential to drive economic development, innovation and productive entrepreneurship in their home countries.

Cons

The Soviet legacy of negative attitudes and restrictive policies towards entrepreneurship continues to influence policy making in several post-Soviet countries.

High levels of corruption undermine productive entrepreneurial development and sustainable institutional reform.

Weak institutional environments stunt business growth and drive entrepreneurs to operate in the informal sector.

Lack of political will and commitment limits the sustainability of programs to support entrepreneurship development.

Author's main message

Governments foster conducive conditions for entrepreneurs through functioning free markets and good governance. In most post-Soviet countries, these conditions are still missing. Lack of political will combined with a detrimental Soviet legacy towards entrepreneurs continues to stunt entrepreneurship development. Some post-Soviet countries have initiated policies and programs to support entrepreneurship, reduce regulatory burden and provide resources and increased access to financing. However, these interventions are rarely combined with broader institutional reform so that their benefits are often limited or short lived.

Motivation

More than thirty years after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the differing paths chosen by the transition countries that made up the former Soviet Union offer insights into how institutions affect entrepreneurial development. Underlying factors of institutional weakness due to corruption, length of communist rule, and lack of commitment to reform and digitalization are some of the main causes of lower levels of entrepreneurship found in post-Soviet countries [1]. Free markets are not enough to sustain entrepreneurial prosperity in post-Soviet countries; rather, supportive institutions are also needed to safeguard the rule of law.

In 2015, Pavel Durov, a successful Russian tech entrepreneur and creator of VKontakte (VK), the Russian equivalent of Facebook, fled from Russia after being pressured by Russia’s secret service to provide encrypted data of VK users. Durov resigned as CEO of VK and in exile, together with his brother, he successfully launched Telegram, a new messaging app. Durov did not return to Russia but continued to live abroad and became a citizen of St. Kitts, an island country located in the Caribbean. Due to Telegram’s tremendous success, in 2021, Durov was listed as one of the world’s top billionaires with an estimated net worth of US $17.2 billion. Although extreme, this example illustrates the type of brain drain and revenue loss post-Soviet countries experience when conducive business environment for entrepreneurial activity is not ensured. A survey of Russian business owners in 2021 indicates that entrepreneurship is still a risky undertaking in Russia: 78.6% of entrepreneurs feel that Russian legislation does not provide sufficient guarantees to protect business from unjustified criminal prosecution. The same opinion is shared by 60.8% of Russian lawyers and 18.4% of prosecutors that also participated in the survey.

Discussion of pros and cons

The importance of institutions for entrepreneurial development

Entrepreneurs and their activities are influenced by opportunities and incentives provided by a country’s context, which is made up of both formal and informal institutions. Put simply, formal institutions are the visible “rules of the game,” such as constitutional law and a national legal code. These rules can be adjusted and altered quickly to adapt to changing economic circumstances [2]. In contrast, informal institutions are the invisible rules of the game, made up of norms, values, acceptable behaviors, and codes of conduct that characterize a given context. Informal rules are usually not legally enforced and tend to take longer to change [3]. Informal and formal institutions often coevolve. Through their collective actions, economic agents such as entrepreneurs can trigger institutional change [4].

Entrepreneurial development is a dynamic process that is influenced by institutional conditions and the existing incentive structure. When the institutional environment is supportive of entrepreneurship, there tend to be larger numbers of productive entrepreneurs—those who create economic wealth through innovation and filling market gaps. To a large extent, productive entrepreneurs abide by ‘formal rules’ by paying taxes and complying with regulations. Conversely, when the institutional environment is less favorable, there are larger numbers of non-productive entrepreneurs—those who engage in activities such as rent seeking from government agencies through privileged monopoly positions or evasion of individual tax and regulatory requirements. In conditions where rule of law is very weak, there is a likelihood of the emergence of destructive entrepreneurs. These types of entrepreneurs engage in criminal activity such as illegal drug manufacturing and sales, smuggling, human trafficking and prostitution or cybercrimes [5]. Different combinations of formal and informal institutional arrangements affect the balance of incentives that induce individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activities, thereby influencing the pattern of economic growth. Productive entrepreneurship contributes positively to economic growth, whereas unproductive and destructive entrepreneurship have a neutral or damaging and negative effect on economic growth.

If the benefits of engaging in illegal entrepreneurial activity outweigh their risks and costs, destructive forms of entrepreneurship are likely to increase in prevalence and interfere with economic development. Conversely, if the incentives are greater for productive entrepreneurship, then this form will predominate and support further economic development. In each case, existing incentives that are influenced by regulations (formal rules) as well as prevailing cultural values and norms (informal rules) play a critical role in shaping the conditions for entrepreneurship development. This does not mean that the same individual will engage in productive, unproductive, or destructive entrepreneurship; rather, different individuals will embark on entrepreneurial activities under different combinations of incentives.

In addition to these three types of entrepreneurship, there is evidence in Russia of state-sponsored violent entrepreneurship, which likely emerged in post-Soviet Russia in the 1990s. This form of entrepreneurship is state sponsored and targets businesses and individuals living both in and outside of Russia, and even foreign governments. Recent examples include cyberattacks from Russian hackers requiring ransom payments and sophisticated organizations that conduct technically sophisticated attacks on governments and businesses globally.

In post-Soviet countries’ initial transition period, the development of formal institutions, such as the adoption of a free-market economy, was prioritized. However, the same level of emphasis was not placed on the development of supportive informal institutions. In the end, this narrow focus on free market mechanisms was not sufficient as it did not safeguard the development of supportive informal institutions such as the reduction of corruption and social acceptance of productive forms of entrepreneurship.

Institutions that matter for entrepreneurship in post-Soviet countries

In the post-Soviet landscape, weak property rights, cumbersome business regulations, lack of trust, and high corruption levels are some of the main impediments to productive entrepreneurship development. Research indicates that property rights play a pivotal role in determining entrepreneurial activity in post-Soviet countries [6]. Weak property rights interfere with business growth since they discourage entrepreneurs from reinvesting profits.

Arguably, the single greatest impediment to productive entrepreneurial development in post-Soviet countries is corruption, which also serves as a good proxy for overall institutional weakness [7]. Corruption is especially damaging since it affects the functioning of formal institutions and negatively influences the development of informal institutions. High levels of corruption can further exacerbate weak property rights, arbitrary state administration, a weak judicial system and an excessive, opaque regulatory framework. Small- and medium-sized businesses are especially vulnerable to corruption in post-Soviet economies because they lack the bargaining power of large firms with respect to state bureaucracies. High levels of corruption further discourage non-corrupt entrepreneurs from starting or scaling-up their businesses, or drive entrepreneurs to operate in the informal economy. In Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, corruption is so pervasive that even successful initiatives to curb corruption have been limited in their ability to reduce “state capture” or ensure a functional system of checks and balances. (State capture refers to a situation in which firms are able to shape the laws, policies, and regulations of the state to their own advantage by providing illicit private gains to public officials).

Another important factor for entrepreneurial development is the length of time spent under communism, specifically as part of the Soviet Union. To a large extent, this characteristic alone explains the differences in entrepreneurial start-up rates across post-Soviet countries. Older generations in post-Soviet economies are far less likely to engage in business start-ups than their counterparts in other regions of the world. By contrast, younger generations have learned to adapt to new conditions and are more inclined to starting a new business. In Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, although former Communist party membership facilitated business set-up, it did not lead to business longevity [8]. This tendency suggests that although former party members and their children had increased access to resources, information and opportunities, they did not possess the entrepreneurial traits needed to facilitate business longevity.

In the literature, networks have been linked to increased entrepreneurial opportunity and business success. Networks denote a system of personal relationships based on trust that provide entrepreneurs access to critical resources (such as information, finance, and labor) and new business opportunities. In the absence of functioning institutions, established networks can become even more important [9]. In the Soviet context, Russians developed network strategies, referred to as “blat,” as a way to obtain scarce resources within the malfunctioning Soviet regime and this practice spread throughout the general population living in Soviet republics. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, blat transformed into an effective tool for the elite (in Russia). Blat’s shift from a network that was open to and utilized by the general public into an elite-only network is attributed to two main factors. First, blat was never rooted in a moral system: even during the Soviet regime, it was seen as “antisocial” and as a way of “cheating the system,” thus carrying amoral connotations [10]. This resulted in blat being easily manipulated toward opportunistic activities focused exclusively on personal gain. Second, since blat functions best by utilizing strong ties, those individuals closest to individuals with power, that is, the elite, are arguably able to benefit from it much more than less well-connected individuals. This has serious implications for broad-based entrepreneurial development, since in the strong-ties based network system, only the individuals in the inner circle of the elite can successfully utilize blat resources for business formation.

Limited access to effective networks within failing institutional environments exacerbated the lack of trust that already existed during the transition process and which continues to characterize post-Soviet countries. Although the interactions between institutions and entrepreneurial dynamics are complex, reducing corruption may be one of the key elements for increasing trust in the government and supporting productive entrepreneurial development.

Several post-Soviet countries have taken important steps to improve the business environment by reducing opportunities for corruption. For example, the Moldovan parliament is seeking to unify and streamline the country’s customs legislation to improve the quality of services provided, reduce costs and delays, and reduce the risk of fraud and corruption through online monitoring of customs operations. This new code is expected to enter into force in 2023. In Russia, a new program was launched in January 2021 to reduce the heavy regulatory burden of outdated regulations faced by businesses.

Adopting e-procurement systems is another strategy that post-Soviet countries are incorporating to reduce costs and the risk of corruption. Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, and Ukraine are developing platforms for e-procurement, e-monitoring and e-reporting. In Ukraine, implementation of the Prozorro project supported by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (ERBD) is estimated to have saved US$ 3.8 billion in public funds from 2015–19. Estonia has taken the lead in e-government services that allow businesses to register, obtain licenses and pay taxes digitally, saving firms time and money. Estonia is estimated to have saved the equivalent of 2% of its GDP by introducing digital signatures.

Transition countries were also uniquely affected by the distorted Soviet notion of “gender equality”, including a resurgence of gender stereotypes and conservative, patriarchal views, that impacted the development of women’s entrepreneurship. Although the Soviet Union pioneered the integration of women into the formal labor market, the Soviet state prevented women from contesting two elements of gender subordination: distributional inequality, or the gendered division of paid and unpaid labor, and the associated status inequality, or the devaluation of work seen as “feminine.” Dissatisfaction with Soviet gender policies became more acute and visible after the Soviet Union’s collapse. In many transition countries, this discontent evolved into broad support for more traditional gender roles and stereotypes within the context of national revival. Such stereotypes can adversely impact women’s entrepreneurship at key stages of business development and growth: At nascent business stages, gender stereotypes limit women’s entrepreneurial intentions and impede access to the knowledge and skills required to start a new venture. At later business stages, gender stereotypes impede women’s development of professional venture networks critical for business growth.

Two differing paths for entrepreneurial development: Estonia vs Russia

The cases of Estonia and Russia provide insights into the differing effects of political will and institutional reforms on productive entrepreneurial development. Estonia has been able to create a thriving institutional environment while support for entrepreneurial development in Russia has been less consistent and effective.

Although institutional contexts are complex, three factors are likely to have contributed to the positive outcomes in Estonia. First, Estonia’s government excelled as an “early adopter” of technology, digitally connecting its population to government institutions soon after it regained independence. These efforts had positive spillover effects for start-ups and business development, including streamlined regulations and a simplified online business registration process. In addition, nearly universal WiFi access supported technology-oriented entrepreneurial development by fostering an internet savvy population and a pool of experienced software developers that had open access to the greater EU market. Estonia was the highest ranked post-Soviet country in the 2021 World Digital Competitiveness Ranking [11].

Second, Estonia benefitted significantly from EU integration in four key ways: (i) the EU provided a standard for “a normal society,” where corruption is not tolerated and entrepreneurship is promoted; (ii) the EU facilitated the direct transfer of functioning institutions from other EU countries that support entrepreneurship; (iii) the EU introduced institutions that reinforce democracy and free market principles; and, (iv) the EU provided direct access to a larger European market for goods and services. Initially, following accession into the EU, Estonia’s GDP per person increased by 30%. At the same time, Estonia continues to be a net receiver of EU funds. However, it is important to note that while EU membership has been beneficial for Estonia, EU accession was by no means a “painless” process; it necessitated extremely high levels of commitment both domestically and in EU bodies to ensure successful institutional reform.

Third, Estonia has excelled at institutional reform. In 2011, seven years after becoming an EU member, Estonia became the first ex-Soviet republic to join the Eurozone. Compared with other post-Soviet countries, Estonia has been ranked near the top in a number of international assessments, including the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index and in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index (see the illustration on p. 1). These rankings demonstrate the success Estonia has achieved in terms of promoting positive institutions and facilitating the development of productive entrepreneurship.

In contrast, Russia’s support for entrepreneurial development has been less focused and uneven. Initially, during the early years of transition, entrepreneurial development was not prioritized due to Russia’s abundance of natural resources, the influence of oligarchs and the state capture of economic policies. However, a recent decline in oil prices (in 2020) instigated a push toward economic diversification and has renewed interest in supporting entrepreneurial development.

In 2010, the Russian government created the Skolkovo Innovation Center in Moscow to nurture development in IT, biomedical, energy, nuclear, and space sectors. In 2019, the Skolkovo Softlanding program was introduced, targeting high-tech foreign companies willing to expand to the Russian market. This initiative has led to an improvement of Moscow’s standing within the international technology scene, though it is still outpaced by many other locations, including Estonia.

However, the total number of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Russia was decreasing even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Since 2016, the number of SMEs has decreased by 6% to 10% per year. Between 2016 and 2019, 50,000 SMEs ceased to exist. The high level of tax burden is one destructive factor in SME development in Russia. In a 2020 survey by Price Waterhouse and Coopers (PwC), Russia ranked among the countries with the highest tax burden, 7% higher than the global average. However, the tax burden in Russia does not correspond to the labor productivity of SMEs, which is significantly lower than in developed countries. As a result, the Russian tax policy performs mainly a fiscal function and is not used to stimulate further business growth and development.

The proportion of business owners who say they do not trust Russia’s law enforcement agencies rose from 45% in 2017 to 70% in 2020, with three-quarters saying Russia’s courts are not independent. Anecdotal evidence indicates that many entrepreneurs are imprisoned for small transgressions where a simple warning would have sufficed. The existence of high-profile arrests intensifies the threat to livelihood that can befall Russian entrepreneurs [12].

Soviet and post-Soviet entrepreneurs

Under Soviet rule, legal forms of private business ownership were severely limited. In the mid-1980s, the individual sale of handicrafts or produce grown on private garden plots was legalized. By the late 1980s individuals were allowed to form limited forms of cooperative style enterprises. But it was only in the mid-1990s that all forms of private enterprise were finally legalized.

Even when it was illegal, certain forms of entrepreneurship existed and even thrived during Soviet rule. The very nature of the planned economy inadvertently promoted the development of widespread illegal entrepreneurial activity, largely as a response to the chronic shortages of consumer goods that plagued the Soviet system. A unique characteristic of this illegal entrepreneurship experience is that it was acquired without the expectation that it would ultimately be useful in a market-oriented system. Research on entrepreneurs with illegal pre-transition experience shows that they are likely to continue operating and growing a business in a market-oriented economy.

In the post-Soviet context, entrepreneurs continue to operate in the informal sector, especially when the governing structures are predominantly corrupt and rent seeking. While informality may be advantageous in the short term, in the long term, businesses functioning in the informal sector are more limited in terms of their access to key resources such as finance, business networks, and support programs. Post-Soviet countries continue to be characterized by large informal sectors, which contribute significantly to official GDP. Estimates range from between 16% to 28% in the three Baltic countries (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) to over 40% in Russia, Moldova, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Georgia. Though data is lacking, in Kyrgyzstan, it is estimated that about 70% of the employed population work in the informal sector, with the majority being micro- and small-scale entrepreneurs.

Another common characteristic of the SME sector in post-Soviet countries is the relatively low level of SME contribution to GDP. For example, there are more than 6.2 million micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in Russia in 2019, accounting for only 22.3% of GDP and employing around 26.3% of the workforce. In Kazakhstan, SMEs employed 3.3 million people in 2018, or 37.5% of the total employed population in the country but contributed only 28.9% to GDP. In Kyrgyzstan, the average contribution of SMEs to GDP has hovered at around 40% since the early 2000’s. However, while the contribution to GDP has remained rather similar, the share of total employment in SMEs significantly increased, from 12.6% in 2001 to 20.3% in 2017, indicating that increased employment has not corresponded to increased labor productivity for SMEs.

There are also growing numbers of self-employed individuals in post-Soviet countries. However, the self-employed should not be confused with individuals who operate a private business as entrepreneurs. It is common for a range of professions, such as consultants, dentists, accountants, and domestic cleaners, to own their own businesses. But entrepreneurs are different. They are involved in innovative activities related to the creation and growth of new ventures.

Entrepreneurship in weak institutional environments

Weak institutional environments enable unproductive or destructive entrepreneurship to develop. Once entrepreneurial activity becomes associated with corruption, rent seeking, and illicit activities, productive entrepreneurs are less likely to engage in entrepreneurship, or, when they do, more likely to move their operations into the informal sector.

Tajikistan provides the most extreme case of institutional failure and lack of support for productive entrepreneurial development. According to World Bank data, Tajikistan’s national income is based on two main sources: remittances (27% of GDP in 2020) and drug trafficking. Domestic entrepreneurial activity is largely focused on the illegal drug trafficking of heroin that is produced in Afghanistan and sold in Russia.

Though lucrative, the high domestic dependence on “illicit entrepreneurship” has a negative effect on productive entrepreneurial development in Tajikistan in four key ways: (i) it has led to corruption within the higher levels of government; (ii) close ties have developed between the government and drug lords, which fosters the rise of a corrupt elite and ineffective law enforcement; (iii) illicit entrepreneurship crowds out the development of productive entrepreneurship in sectors most targeted for criminal investment such as bars and restaurants, construction, wholesale and retail trade, transportation, real estate activities, and hotels; and, (iv) the weak institutional environment has led to state capture and control of the media. In Tajikistan, as in other countries with weak institutional environments, it is common to find larger numbers of entrepreneurs starting businesses “out of necessity” and operating in the informal sector rather than founding “opportunity-driven” businesses in the formal sector.

The technology sector can provide opportunities for entrepreneurs to start and grow businesses, even in countries where institutions are weak. Entrepreneurs operating in the technology sector tend to be less affected by the prevailing corrupt conditions due to four reasons: (i) lower start-up costs; (ii) the ability to function under the radar, even informally at first, in a largely unregulated, non-monopolized and less corrupt sector; (iii) ease of mobility within and beyond a country’s borders; and, (iv) the potential for rapid growth and high profit margins.

However, there are also disadvantages for technology sector growth and expansion in weak institutional environments. For example, internet access is costly and slow in Tajikistan, which interferes with the growth of tech start-ups. Additionally, the relative immaturity of the technology sector in post-Soviet countries in Central Asia results in a lack of access to the key resources needed for tech sectors to expand and grow (such as mentors, informal “angel” investors and partners). Moreover, the technology sector can become a silo: entrepreneurs who are successful in the technology sector may encounter difficulties in entering other lucrative economic sectors due to existing monopolies or corrupt practices.

Limitations and gaps

The main limitation for conducting entrepreneurship research in post-Soviet countries is the lack of reliable comparative data on entrepreneurship and business development. Data sets such as the OECD and Eurostat Entrepreneurship Indicators Program, or the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s data contain a sub-sample of some of the more economically advanced post-Soviet economies but are not sufficient for conducting thorough cross-country analyses. Data on post-Soviet countries with limited international engagement such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have largely not been available.

Though notoriously difficult to collect, comparative estimations on the size and scope of informal entrepreneurship in post-Soviet countries could provide a more accurate account of how institutions affect entrepreneurial outcomes in post-Soviet countries.

Further knowledge gaps exist when it comes to understanding which combination of policies, programs, initiatives, free press and media, civic engagement, social norms, civil servant wages, and/or job rotation may have a long lasting and positive effect on reducing the effects of corruption on business startup and growth. More research is also needed on how informal institutions such as beliefs and attitudes shape entrepreneurial development. Specifically within the post-Soviet context, a better understanding is needed about how deeply rooted views affect entrepreneurial development and how they can be adapted to create an enabling environment for productive entrepreneurial development. Additional qualitative insights are also needed on how different forms of entrepreneurship influence institutional change.

Summary and policy advice

More than 30 years since the breakup of the Soviet Union, many post-Soviet countries are still grappling with the legacies of their Soviet-style institutions. Corruption and weak rule of law continue to inhibit the development of productive entrepreneurial development in many post-Soviet countries. The formal and informal institutional environments play critical roles in shaping incentives that drive the allocation of entrepreneurial talent to productive and non-productive activities. Therefore, it is paramount that policies address both the formal and informal institutions that impede entrepreneurial development. Institutional and policy initiatives that focus on reducing regulatory burdens are important but must also be combined with reduced corruption and a commitment to long-term economic, political, and institutional reform.

International integration such as EU membership has provided a solid template for building institutions that reinforce democracy, free market principles, and support entrepreneurial development. These effects are visible in countries like Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, who joined the EU in 2004. The EU is also significantly supporting economic development and entrepreneurship in post-Soviet countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia. The Asian Development Bank and the World Bank are providing support through projects in post-Soviet countries in Central Asia such as Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. Other international membership organizations such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) or the World Trade Organization (WTO) may also help sustain commitment to the institutional reforms needed to foster productive entrepreneurial development through their activities in post-Soviet countries.

However, even where rule of law is weak and corruption high, the new globalized, digitized world economy provides opportunities for technology-based entrepreneurs to interact with a broader market and, if needed, operate informally. To be successful, these entrepreneurs may need to leave their home countries and immerse themselves in more conducive environments located in advanced market economies with technology hubs such as Silicon Valley, London, Tokyo, or Paris. While abroad, they can access those locations’ existing funding opportunities and support networks, launch their products or services in mature foreign markets, and then duplicate their business model back in their home country. These entrepreneurs can serve as much-needed role models and potentially play a future role in fostering the institutional change needed for developing a productive entrepreneurial society.

Instead of restricting movement out of a fear of brain drain, it would be wise for post-Soviet countries to cultivate close ties with their diaspora by allowing dual citizenship, removing the barriers for returning entrepreneurs and supporting professional diaspora networks. Returning entrepreneurs can bring knowledge, capital, and networks, which may be the missing piece for jumpstarting economic development through increased innovative entrepreneurial activity. Informal networks of investors can be encouraged within the business community or through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to provide capital and mentorship to entrepreneurs in their home countries.

Successful institutional reform may not be enough to retain entrepreneurship capacity given the small size of the domestic market and limited talent pool in some post-Soviet countries. Encouraging diversity through immigration may provide benefits for expanding the scope of productive entrepreneurial activity. To expand its entrepreneurship base, Estonia’s e-residency program allows entrepreneurs, regardless of nationality or citizenship, to register their internet-based businesses in Estonia without ever physically establishing themselves there.

Although it is relatively easy to identify impediments to entrepreneurship in the post-Soviet context, such as corruption and excessive regulations, it is far more difficult to alter these practices. Unwavering and focused commitment on the part of key stakeholders, including the government, is critical to push through often unpopular yet necessary stages of the reform process. Several new anti-corruption laws, programs and strategies were recently introduced by post-Soviet governments. In 2020, Maia Sandu was chosen as the new President of Moldova. Her campaign focused on addressing corruption and ending the “rule of thieves.” In October 2020, Kazakhstan amended legislation to strengthen its anti-corruption framework, which included an absolute ban on giving gifts to public officials and members of their families. Russia and Kyrgyzstan have both adopted extensive anti-corruption strategies for 2021–2024. In Armenia, the parliament adopted a law creating a new anti-corruption body with stronger investigative and enforcement functions in March 2021. This was followed by the adoption of legislation establishing a specialist anti-corruption court to handle corruption-related cases. Also in March 2021, the Ukrainian parliament approved a law strengthening the independence of its anti-corruption bureau. While, at face value, these are all positive developments, it is still too early to say if these initiatives will lead to institutional reform that supports productive entrepreneurship development. Likewise, it remains unclear to what extent political will is committed to ensuring that the resulting reforms will lead to long-lasting institutional improvements.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The responsibility for opinions expressed in this paper rests solely with the author, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Organization. Version 2 explores new aspects such as state-sponsored violent entrepreneurship, gender stereotypes, and party membership and discusses latest steps taken to improve business environment. It also adds new Key references [7] and [8].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Ruta Aidis