Elevator pitch

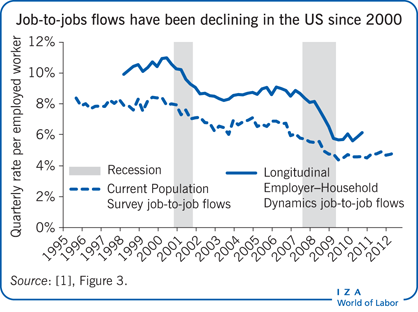

As part of a more general process of employment reallocation from less to more productive employers, job-to-job flows tend to be beneficial for productivity and for workers. Thus, when this rate slows, it is important to understand why. In the US, for example, the job-to-job flow rate is now at an all-time low. While job-to-job flows are a means of boosting wages and productivity, a decline could indicate improvements for workers if it means that they are now better matched to their jobs. Furthermore, when job-to-job flows are lower, firms and workers incur fewer costs related to job transitions, such as job search and hiring costs.

Key findings

Pros

Job-to-job flow rates are generally the result of voluntary quits for better jobs.

Changing employers usually involves a wage increase, especially for young workers.

Job-to-job flows are part of efficiency-enhancing resource reallocation: productive employers tend to expand, and less productive ones to contract.

Workers are generally in their jobs longer after switching employers.

Changes in labor market composition, such as the aging workforce, rising educational attainment, and declining entrepreneurship, explain some of the decline in the job-to-job flow rate.

Cons

Job transitions are costly: workers have to look for work, and employers must post vacancies and interview new applicants.

Worker-accumulated job-specific skills may not be put to productive use after a worker changes jobs.

Some direct job-to-job flows are involuntary, and these often involve worse matches and pay cuts.

The main causes of the decline in the job-to-job flow rate are unknown.

Little information is available on job-to-job flows in countries other than the US.