Elevator pitch

The Covid-19 pandemic has produced unprecedented negative effects on the global economy, affecting both the demand and supply side. Its consequences in terms of job losses have been important in many European countries. A large number of firms have been forced to dismiss at least part of their workforce or to close down all together. Considering that young people are usually penalized more than their adult counterparts during economic crises due to the so-called “last-in-first-out” principle, it is worthwhile to evaluate if the youth will also end up paying the highest price during this pandemic-induced recession.

Key findings

Pros

Young people are on average more educated and flexible than adults and thus more able to react to economic changes.

Young people have significantly higher digital competences, which is very important in the Covid-19 crisis.

The prolonged suspension of many productive activities could lead to closure, involving employees of any age.

Young fathers and mothers have been almost equally hurt by the pandemic, with some differences across countries.

Due to their flexibility, young people have secured new jobs related to digitalization of consumption and production, and will likely benefit most from the after-pandemic recovery.

Cons

Young people lack work experience and ability when job searching.

Young people often lack soft skills.

At EU level, the ratio between the youth and adult unemployment rate increased significantly during the first year of the pandemic.

Young people are victims of the “last-in-first-out” principle.

Young people are over-represented in informal jobs and in sectors most hit by the pandemic, such as entertainment and recreation as well as accommodation and food services.

Author's main message

Was the pandemic a “youth-cession”? The pandemic has yielded dramatic consequences in terms of job losses and firm closures almost everywhere. Empirical evidence suggests that the drop was more severe for young people as compared to adults, with little systematic gender differences. The primary reason is that young people are mainly employed via temporary contracts in the sectors most hit by the pandemic. Policymakers should focus on generating sustained and stable economic growth to enable markets to reabsorb the high youth unemployment caused by the pandemic crisis.

Motivation

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a devastating economic recession yielding loss of income, worsened economic prospects, reduction in household consumption and firms’ investment, and, consequently, massive layoffs. On the supply side, prolonged lockdowns, business closures, and social distancing caused the slowdown of many productive activities, global supply chain disruptions, and closures of factories. Currently, extreme uncertainty about the future path and duration of the pandemic recession is dampening business and consumer confidence and tightening financial conditions. This could possibly lead to further job losses and investment slowdowns in the near future. This article examines the extent to which young people have been affected across European countries during the Covid-19 pandemic, based on the first available Eurostat data (until the third quarter of 2020). Due to the lack of homogeneous and comparable statistics, the focus of this article is mainly on EU countries, although it would be interesting to compare with the US situation and that of developing countries.

Discussion of pros and cons

The Covid-19 contagions in Europe started, at least officially, in February 2020, initially in Italy, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg and then on to Germany and Austria. Quite soon after, the pandemic had spread to Switzerland, Spain, Portugal, France, Sweden, Ireland, and the UK. The second wave, beginning in the autumn of 2020, was more severe and spread almost evenly across European countries. In October 2020 a third wave was fueled by virus mutations. While vaccines were available by this time, their rollout was slow at first and they were thus unable to halt the virus. The autumn of 2021 saw the advent of a fourth wave, affecting mainly the so-called “anti-vaxers.”

The effects on GDP and unemployment registered in 2020 are only the first signs of a much deeper crisis that has already led to the final closure of many enterprises and economic activities.

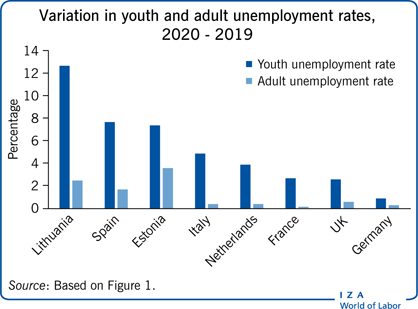

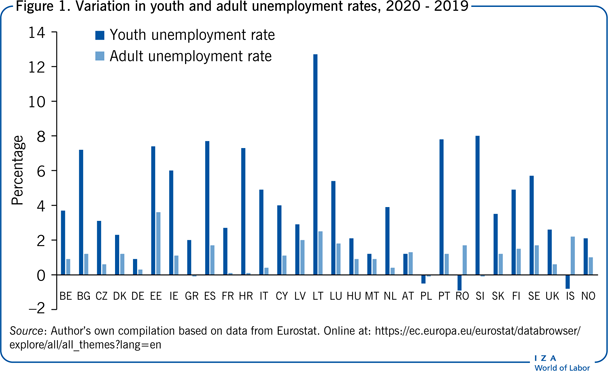

The pandemic recession has totally changed the labor market worldwide. In this harsh scenario, it is important to understand which segments of the population have been most affected. The age dimension is one of the most important from the supply side. This article examines differences among young people (15–24 years old) and adults (25–74 years old), highlighting the extent to which the pandemic was a so-called “youth-cession” [1] (Figure 1). Beyond age, another key factor is gender: being female and young are indeed two traditional factors of disadvantage in the labor market, though in recent years the gap among young men and women has dramatically reduced, mainly due to the increasing educational level of women. It is likewise important to determine whether young women have fared worse than young men during the pandemic.

The pandemic recession

The pandemic recession occurred in an already complex economic scenario. For many countries, not only within the EU, recovery from the previous global financial crisis of 2007–2008 was still not complete, and the unemployment rate, especially for young people, was still very high. Within the European framework, this was especially the case in Italy, Spain, and Greece. In these countries, in the first months of 2020, the unemployment rate, especially that of youth, was still far from pre-crisis levels. Moreover, these countries registered low growth rates and were slow to adopt the digital and green revolutions. The continental and northern EU countries experienced an opposite economic scenario while the eastern European countries, even if starting from lower-than-average levels of GDP, were experiencing a higher-than-average GDP growth, slowly but steadily reducing the gap with the most developed EU economies.

The Covid-19 pandemic reached European countries in the first quarter of 2020, but it hit some countries more severely than others. Actions taken to counteract the pandemic were very different across countries as well. Some, such as Sweden, adopted less restrictive measures; in principle this should have led to less severe economic impacts in the short term, but not in the long term. Other European countries instead decided to combat the pandemic by prohibiting many economic activities and obliging their inhabitants to stay home for prolonged periods of time. Such actions were intended to reduce the chances of infection, but they also reduced spending and consumption, thereby causing a significant interruption of many economic activities. Despite these different national approaches, some first evidence shows that the global nature of the negative supply and demand shocks triggered by the lockdowns produced a severe economic crisis almost everywhere [2]. A recent stream of literature analyzes the effects of social distancing measures on labor supply, finding a greater impact on the jobs in non-essential activities that cannot be performed from home. The most impacted activities were in the tourism sector, restaurants, and retail services. Other activities, such as food stores, were instead experiencing increasing revenues.

The most direct and immediate impact of the pandemic occurred on GDP, which quickly shrank almost everywhere. Considering variations in GDP registered in the second quarter of 2020, when the first wave of the pandemic severely hit only some European countries, Spain and the UK experienced the strongest negative consequences, with a decrease of more than 20 percentage points. The other Mediterranean countries of France, Italy, Portugal, Croatia, Greece, and Malta followed suit, with GDP losses higher than 15 percentage points. Conversely, countries with the lowest GDP losses of around 7 percentage points, were, in order: Slovakia, Ireland, Lithuania, Finland, and Estonia. All the other Nordic and central European countries were in between.

However, when comparing GDP registered in the first and fourth quarters of 2020, the only nations which confirmed the negative trend were the UK, with a loss of 9.9% during that span, followed by Portugal and Malta, whose losses were less than 1 percentage point. All other European countries registered an increase, with particularly high increases seen in Romania (+42%) and Bulgaria (+25%).

Young people and the labor market

The sharp fall in GDP seen in the first half of 2020 had a swift impact on unemployment. Indeed, most governments tried to contrast the reduction in worked hours by introducing income support and fiscal measures to sustain enterprises, thereby avoiding their closure. In some cases, governments intervened with measures blocking layoffs. Despite this, many jobs were lost, and unemployment rates increased almost everywhere. The first statistical estimates show that the most penalized population groups in terms of job losses were young people and women; but, as discussed below, mainly adult women.

It is well-known that young people represent one of the most vulnerable segments of the population [3]. With reference to the previous economic crisis, a 2011 study on the EU and US estimates that a 1% increase in the adult unemployment rate corresponded to a 1.79% increase in the youth unemployment rate [4]. The youth unemployment rate is indeed typically more severely influenced by economic fluctuations [3], [5]. Recent evidence shows that the recent pandemic recession is no exception.

Reasons for youth's specific sensitivity to business cycles are manifold. In principle, the share of the tertiary educated is significantly higher among youth, as is their digital competence, which is particularly important in the context of the pandemic crisis.

However, despite such perceived advantages, young people usually encounter greater obstacles finding jobs because of their lack of work experience [3] and, as some recent research suggests [6], their lack of experience in searching for a job. Moreover, when making firing decisions, firms often apply the “last-in-first-out” (LIFO) principle. The fact that young workers have less firm-specific human capital and fewer children to support is used to justify seniority rules, which favor adults over young people [3].

Furthermore, ever more often, young people are likely to be hired on temporary labor contracts, which are the easiest to discontinue in the case of a reduction in demand for a firm's products. Temporary labor contracts may represent an entry point into the labor market, but also serve as a buffer to deal with sudden demand fluctuations. Temporary workers are more likely to be laid off without incurring statutory redundancy payments or restrictions imposed by employment protection legislation. Conversely, adult workers have been more protected during the pandemic by several income support schemes. Such schemes, including those placing restrictions on firms’ ability to fire employees, concerned, almost exclusively, workers in regular jobs.

On the other hand, when dramatic recessions cause plant closures, rather than employment reductions at the margin, they involve adults more frequently than young people, since adults make up the bulk of employment for established firms. Moreover, most planned new hires were frozen during the pandemic, which also has stronger consequences for young people, who are of course more numerous among job seekers.

Another important aspect to consider when identifying the most affected segments of the population during the pandemic is the distribution of young people across economic sectors and job positions. Almost everywhere, young people are more concentrated in hard-hit sectors. For example, ILO and European Commission estimates show that 77% of the world's young workers were in informal jobs, compared to around 60% of adult workers. Furthermore, the presence of young people is disproportionately high in leisure sectors, such as sport, the arts, and entertainment, as well as other non-essential activities, which are typically suspended during a pandemic.

The first pioneering studies on the effects of the pandemic on the labor market seem to confirm that young people were the worst hit. One such study from 2020 shows the most severe impact of the pandemic on young people also in terms of reduced job opportunities and career prospects in the UK [7], while another study highlights that young people were most affected in the first months of the pandemic in Spain, with greater transitions from employment to other labor market statuses [8]. Yet another relevant 2020 study finds the same outcome looking at the contracts for training and internships, involving mainly young people [9].

Another key factor affecting the comparison between youth and adults in the labor market is the gender dimension. While the 2007–2008 economic recession hit men more severely than women, as women are usually concentrated in less cyclical jobs such as health and education, the pandemic crisis had an outsized impact on female employment [10], [11]. Indeed, even if the gap in time spent by men and women in homework and care activities for children and the elderly has reduced in recent years, women still carry the majority of family caregiving responsibilities. A recent publication by Eurostat shows that 17% of part-time female workers in the 15–29 age group cited taking care of family and children as motivation for their choice of part-time work, compared with only 2% of men in the same age group.

The “stay at home” imposition, with consequent closure of schools and disruptions in day-care centers and after-school programs penalized in particular women with children. Furthermore, women of all ages are more likely to provide unpaid care for elderly relatives, an activity that has also been exacerbated by the pandemic. Some pioneering studies on UK couples show that both women and men have increased the time spent with their children during the pandemic, but the increase has been greater for women. Moreover, a survey of parents in the US during the pandemic shows that mothers do more than fathers with respect to home schooling, with similar results coming also from Europe. These results indicate a strong need for further investigation to verify whether and to what extent young people and especially (young) women may be worse off due to the pandemic recession.

Empirical evidence

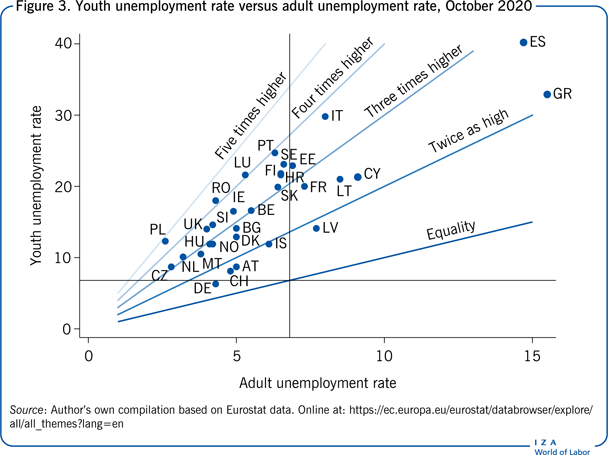

The ratio between youth and adult unemployment is typically used to measure the relative disadvantage of the former [3]. In 2019, before the pandemic exploded, the ratio was equal to an average of 2.50 at the EU28 level. In 2020, during the pandemic, it increased progressively to 2.65 in the first quarter, until 2.76 in the third quarter, the last period for which data are currently available. Comparing unemployment levels in October 2020 to January 2020, the adult unemployment rate increased by 0.90 percentage points for the EU27 countries, against an increase in the youth unemployment rate of 2.6. In other words, the relative increase was 2.89, which is greater than in the previous economic and financial crisis. It is therefore apparent that in the first year of the pandemic young people were penalized more than adults, at least for the majority of countries. However, it is interesting to verify what differences may exist across countries.

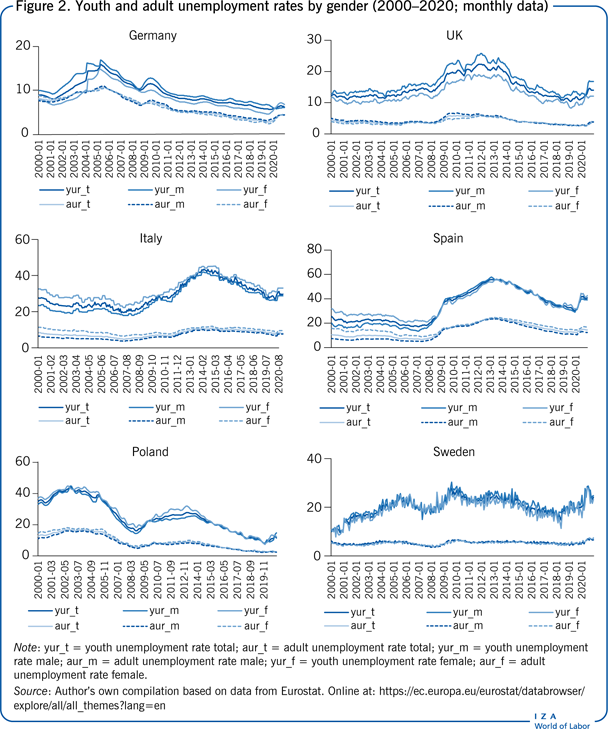

Unemployment levels for both youth and adult populations registered an increase almost everywhere during 2020, after a long period of decline following the recovery from the previous economic crisis. The paths for youth and adult unemployment rates by gender for some representative European countries over the last 20 years are shown in Figure 2.

As is well-known, quite atypically in comparative terms, Germany exhibits a low relative disadvantage between young people and adults, with the youth unemployment rate being only slightly higher than that of adults. Moreover, the gender gap in unemployment rates, as shown by the distance between the trend lines of men and women in Figure 2, was already in favor of women from the mid-2000s, both among young people and adults. However, over the pandemic, there seems to be a worsening of the female unemployment rate among both youths and adults. This is probably due to the impact of the pandemic on such female-dominated sectors as tourism, retail trade, and private services in general.

In the UK, Italy, Spain, and Poland, the relative disadvantage of young people, as measured by the distance between the trend lines of youth and adult unemployment rates in Figure 2, appears sizable, even if in recent years, until 2019, it tended to decrease. In contrast, in Sweden the youth gap has increased in the last years. During 2020, unemployment rates in all countries increased, but especially those of young people. As a consequence, the gap between young people and adults tended to further increase almost everywhere during the pandemic recession, with the exception of Germany.

Last, but not least, while in most countries young women tended to worsen their position in comparison to young men, in the UK exclusively, young men appear to have been penalized more than young women. In general, due to the pandemic, the gender gap for young women has largely grown, reversing many of the gains they seemed to have made in recent years. Nonetheless, it is apparent that the pandemic hit adult women harder than young women.

Unemployment rates started to increase globally in the second quarter of 2020, and further increased in the third quarter, reaching their maximum levels. However, while the increase in adult unemployment was less than 2 percentage points, the increase in youth unemployment rates exceeded 8 percentage points in Latvia, Croatia, and Slovenia, and was higher than 2% in most other countries.

The levels of youth and adult unemployment rates in October 2020 for all European countries (EU27 plus the UK, Norway, Iceland, and Switzerland) are compared in Figure 3. The countries underneath the “twice as high” line are those where young people have the lowest disadvantage; in no country is the disadvantage lower than 1. The countries with the smallest gaps are the continental countries of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, while Iceland and Latvia are also close to the line. All other countries exhibit a disadvantage at least twice as large for young people versus adults. Youth unemployment rates are three times greater than those of their adult peers in Poland, Romania, and Luxembourg. Italy and Portugal follow just behind, as they are near to the “four times higher” line (for a comparison with the pre-pandemic times, see [3]).

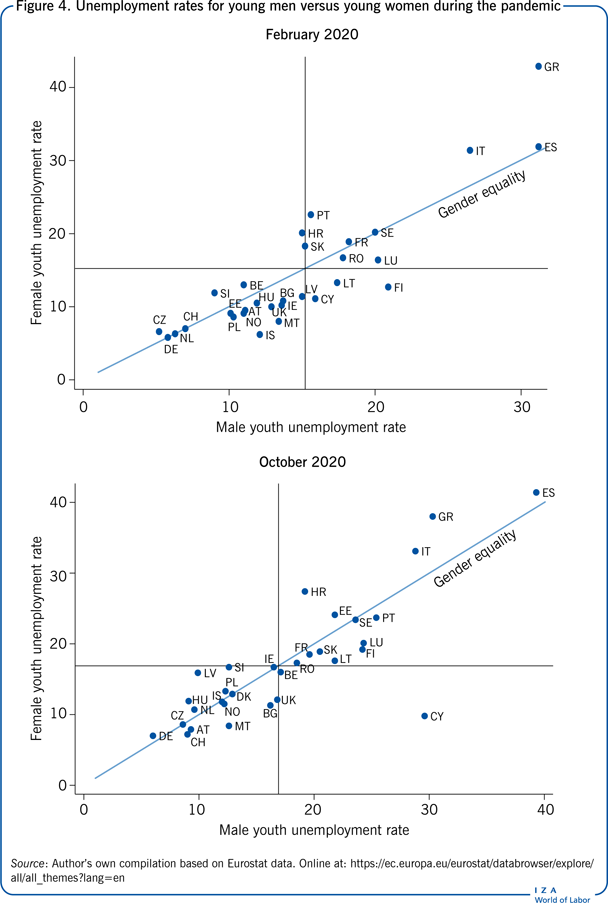

The condition of youth in the labor market by gender in February and October 2020, respectively, is compared in Figure 4. In this figure, only the bisector line which represents the case of equality among young men and young women is shown. Comparing youth unemployment for men and women before (in February) and during (in October) the pandemic, European countries differ substantially from each other. In Iceland and Ireland, young women were by far more penalized than young men during the pandemic. Indeed, the increase in unemployment for young women was 5 percentage points higher than for men. Estonia and Finland exhibit a worsening situation for women as well, though of lesser magnitude. By contrast, men were penalized more than women in Belgium, Cyprus, Portugal, and Slovakia; these countries plots tend to move from above to below the equality line. This essentially means that gender is not a consistent determinant of the gap among young people. In other words, young women were not always the most penalized. In some countries, young men fared worse than young women.

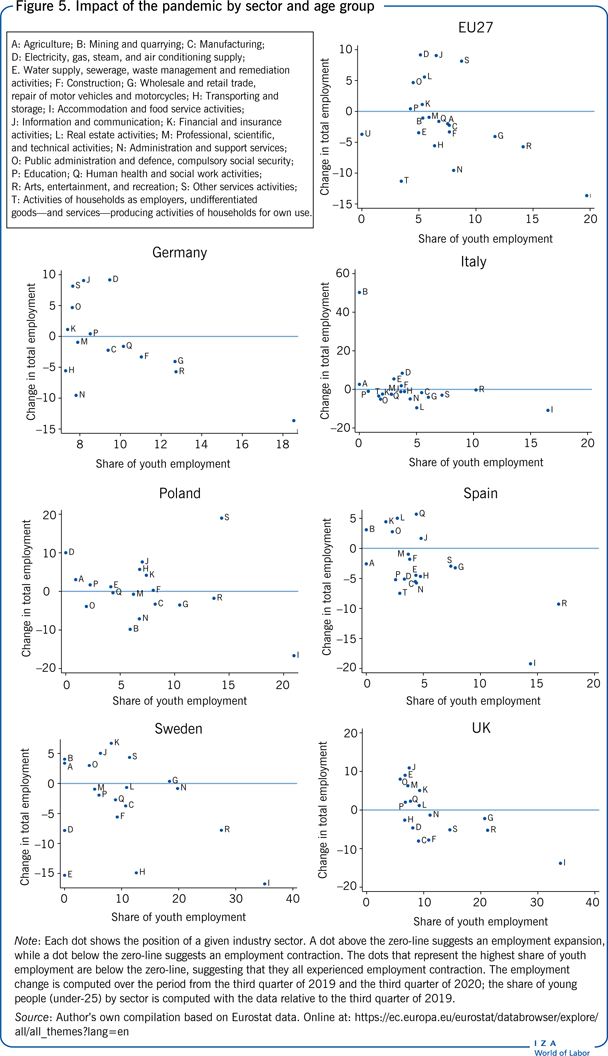

To understand the different degrees to which the pandemic has affected young people across countries, the distribution of youth employment across industry sectors within each country is of interest. The youth employment share is then compared with the total employment increase or reduction experienced in each sector. This analysis was conducted through an ad hoc elaboration on Labour Force Survey data, latest wave available (from the third quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2020). The results of this descriptive analysis for a number of EU countries for which comparable data were available are presented in Figure 5. The horizontal axis reports the share of youth employment, while the vertical axis reports the change in employment share experienced in each sector. Each dot shows the position of a given sector of industry. A dot above the zero-line suggests that the given sector experienced an employment expansion, while a dot below the zero-line suggests that the given sector experienced an employment contraction. Clearly, the dots that represent the highest share of youth employment are below the zero-line, suggesting that they all experienced employment contraction. In almost all countries, young people are disproportionately represented in the sectors most hit by the pandemic. These sectors include “Wholesale and retail trade”; “Repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles”; “Accommodation and food service activities”; and “Arts, entertainment and recreation.”

Limitations and gaps

The available data relevant to this field are still fragmented and, hence, do not allow researchers to identify the causes of the different outcomes registered across countries in terms of job losses. More in-depth studies capable of capturing these determinants should be conducted when microdata become available. Some recent studies, based on recently released enterprise survey data, are providing the first accurate analysis of the sectors most hit and of the employment effects of the pandemic [12], [13].

The analysis provided in this article is necessarily limited, as it does not consider the complex consequences of the pandemic recession on youth labor market behavior. There are at least three other ways through which the pandemic recession could have affected the participation of young adults in the labor market: (i) Through welfare damage: young people have no income and face quality of life issues. (ii) Through human capital depreciation: they stay away from the labor market and are thus unable to exercise their skills. (iii) Through the deterioration of mental health: lockdowns force people to stay indoors and reduce or eliminate the possibilities for social contacts. Therefore, young people face psychological problems and may struggle to efficiently search for new jobs.

These three factors are likely to produce a scarring effect, with consequences not only in the short, but also in the long term. All these aspects are fields for future research.

Summary and policy advice

The unprecedented economic crisis due to the Covid-19 pandemic has totally changed the world economy and with it the labor market. In this harsh scenario, young people are paying the highest price in terms of job losses, thereby increasing the employment gap with adults. From January to October 2020, in the EU27 framework, youth unemployment increased almost three times more than adult unemployement. Countries where young people were hit the hardest (Mediterranean countries, Estonia, Latvia, and Sweden) are mainly those where young people are more concentrated in economic sectors that were more penalized by the pandemic, such as the tourism and entertainment industries.

It is clear that with the diffusion of vaccinations and the reduction in infections, intensive care cases, and deaths, the need to lockdown will reduce and the economy will gradually return to its pre-pandemic equilibrium. However, without the re-launch of a strong and robust growth process, the recovery will not be possible in a sufficiently quick and stable way. The European continent needs important public investment in material and immaterial infrastructures that are incompatible with policies of fiscal consolidation. After decades in which the EU has pronounced “sad words” regarding the need for expansionary macroeconomic policy, for the first time in a long period, European governments have provided an unprecedented response: the so-called Recovery Fund or Next Generation Fund, which promises to form the bulk of an EU public debt and stable expansionary fiscal policy. For countries more severely hit by the pandemic, but also for those that experienced lower economic growth and productivity in recent years, this fund could represent an unprecedented opportunity to boost public and private investments in the green economy and digitalization. Such investment would help reduce the gap between the least and most advanced EU countries and would provide strong incentives to favor more stable economic growth, which is the first pre-condition for young people to reduce their disadvantage.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also gratefully thanks Prof. Antonella Rocca for providing support in the collection of data and elaboration of descriptive statistics.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Francesco Pastore