Elevator pitch

In the popular immigration narrative, migrants leave one country and establish themselves permanently in another, creating a “brain drain” in the sending country. In reality, migration is typically temporary: Workers migrate, find employment, and then return home or move on, often multiple times. Sending countries benefit from remittances while workers are abroad and from enhanced human capital when they return, while receiving countries fill labor shortages. Policies impeding circular migration can be costly to both sending and receiving countries.

Key findings

Pros

Circular migrants fill labor shortages in host countries.

Migrants do not stay in host countries if they cannot find work.

Remittances sent home by migrants contribute crucially to the economic development of the sending countries.

Circular migration reduces the brain drain and encourages the transfer of skills and know-how (“brain circulation”).

Circular migrants benefit from mobility.

Cons

Restricting circular migration increases the likelihood of illegal immigration and overstaying of visas in receiving countries.

Restrictions may result in more non-economic migrants, including family members and people on welfare.

Outmigration can lead to labor market shortages in sending countries.

Circular migrants may remain stuck in low levels of employment and may be exposed to abuse, exploitation, and discrimination.

Author's main message

International labor migration is typically circular, involving non-permanent moves back and forth between home and foreign places of work. Policies that restrict worker mobility often backfire, with workers resorting to illegal means of entering the country, bringing their family with them, and no longer returning home. Restricting mobility may therefore induce losses of welfare. Free labor mobility is more likely to generate benefits for all sides. Supportive policy instruments include dual citizenship, permanent residence permits, and open migration agreements between countries.

Motivation

In popular opinion, migration is about foreigners being attracted by Western countries’ generous welfare systems and wanting to move permanently to the receiving country. In reality, a large share of migrants move for work-related reasons—and do so on a temporary basis. The movement of labor migrants is therefore often circular: They move back and forth between their homeland and foreign places of work. This circularity suggests the potential of a win-win-win situation for migrants and the sending and receiving countries.

When policymakers misinterpret the real motivations underlying workers’ migration decisions, the results can be costly not just for individual migrants but for society as well. Exploitation, discrimination, and other undesirable conditions can turn the great freedom of labor mobility into a modern form of slavery.

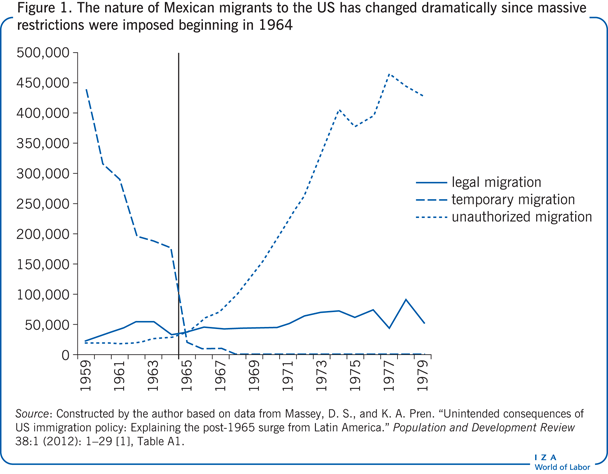

An example of the effects of poorly reasoned immigration policies is the broad-based effort to restrict the circular flow of workers between Mexico and the US in the 1960s and 1970s. Those policies have transformed legal, temporary migration into permanent, unauthorized or illegal migration [1].

Discussion of pros and cons

Creating a win-win-win situation

Circular migration can become a self-perpetuating, self-sustaining process. Knowledge acquired during migration creates migration-specific capital that encourages future movements.

For receiving countries, circular migration can help fill sectoral labor market shortages by matching excess labor demand in receiving countries and excess labor supply in sending countries. In the 1950s and 1960s, millions of low-skilled laborers from southern Europe were recruited to work in the industrial sector in West Germany and other Western European countries, where labor shortages were slowing economic growth [2].

Circular migration enables transnational social networks to arise that can provide information to potential migrants about job vacancies in the receiving country and provide information about human resources in the sending country to employers in the receiving country. Circular migration thus offers firms in the receiving country recruitment from a known and reliable pool of workers, keeps wages low, and reduces illegal migration [3], [4]. Such highly developed networks worked very well, for instance, for Mexican workers in the 1940s who frequently commuted between their home villages in Mexico and workplaces across the US border [1].

Circular migration can buy time for receiving country governments and employers to train native employees to meet labor shortages and can have a rejuvenating effect on aging societies. Because free movement back and forth keeps migrants’ options open in both home and host countries, it reduces the risk of long-term settlement in the host country and illegal overstaying of visas. By explaining migration in these terms, policymakers might make a more compelling case to their electorates for policies that promote circular migration [5].

Sending countries benefit from circular migration as well. Circular migrants tend to send more money home as remittances than migrants who do not intend to return home [4], [5]. These remittances help reduce poverty, and seed investments in human capital and productive assets such as enhanced infrastructure [6]. Remittances also help improve food security, stimulate markets, and increase local wages, thereby accelerating demand for local goods and services and stimulating new job creation.

Higher-skilled migrants who do return home are valued for the knowledge and skills they have acquired abroad and for the new ideas they bring back that can foster innovation. In addition, they maintain non-family networks and productive links in the receiving country that can advance development in their home country. Returning migrants may also start new businesses in their communities of origin. For sending countries, circular migration thus reduces the negative effects of brain drain and encourages brain circulation.

Circular migrants tend to optimize and re-optimize their income, saving, and asset strategies, and thus improve their economic, social, and personal situations at each stage in the migration cycle [4]. Simultaneously, they minimize search, relocation, and emotional costs, and build up local capital in receiving and home countries. All these benefits give them an advantage over both non-migrants and return migrants who have only a single migration experience.

Illegal overstaying, brain drain, and exploitation of migrants

Migration also entails a number of risks for both the receiving and sending countries. Potential difficulties for receiving countries include compliance problems, including illegal visa overstays. After guest worker recruitment programs in European countries were halted in 1973, incentive measures to encourage return migration proved largely unsuccessful [2], [4]. Because circular migrants do not stay permanently in the receiving country, integration efforts and integration opportunities have been limited. This has created social tensions in the past and requires specific policy measures to forestall new tensions.

For the sending country, outmigration can induce severe labor shortages and worsen poverty. In addition, remittances might be smaller than they otherwise would be because of excessive rent-taking. Transaction costs can be higher for legal migrants than for illegal, undocumented migrants, who tend to circumvent payments to recruiters, government officials, and travel providers, as well as payments for documents and training. Legal migrants, who do pay those charges, may thereby incur debt, reducing their capacity to send remittances. Furthermore, sending countries still risk a brain drain if highly skilled migrants do not eventually return home [5].

In some cases, circular migration can be harmful to migrants if they are exposed to exploitation or are locked into dependent and exploitative relationships that offer little possibility of upward mobility and training in the receiving country. Potential problems in the destination country include lack of employment protection and opportunities for integration, and exposure to anti-migrant attitudes and behaviors. In the home country, re-integration possibilities might be limited, due to poor governance in migration institutions and few investment opportunities [5].

Characteristics of circular migrants

While circular migration occurs extensively throughout the world, its extent is difficult to measure. Thus the available empirical findings may be selective.

Evidence from sending countries

Albania

About 25% of Albania’s working-age population (ages 15–64) was either living abroad or had past migration experience, according to a 2005 household survey. Most of Albania’s circular migrants, who represented about 80% of its migrant population, migrated to geographically proximate regions in Italy and Greece, where they were employed as seasonal workers in construction, farming, tourism, manufacturing, and service industries. Most circular migrants were men, were younger on average than the non-migrant population, had only a primary education, and came from rural and less-developed areas. Many were members of poor, large families, and most had migrated for employment. Their return was often prompted by the expiration of seasonal or temporary work permits. Workers who intended to migrate permanently were more likely to choose distant countries such as Canada and the US. Among those who returned to Albania, migrants with the least formal education were the most likely to engage in repeat migration, taking advantage of better job opportunities for low-skilled workers abroad [6].

India and Asia-Pacific

A combination of push and pull factors drive circular migration in India: low income, unemployment, low agro-ecological potential, debt, poor access to credit, and high population density. In the Asia-Pacific region, particularly in Indonesia, labor migration has been a dominant feature in the poorest areas of the country [5]. This has also been the case in northern Malaysia, which has experienced a sizable inflow of migrant workers from southern Thailand.

Evidence from receiving countries

The Netherlands

A large percentage of immigrants to the Netherlands (between 20% and 50%) do not stay permanently but return to their home country or move on to another country. The percentage is similar for Denmark: 20% of immigrants to Denmark left the country between 1986 and 1995 [7]. Data from Statistics Netherlands show that, among migrants, those who are unmarried are the most flexible and mobile. Mobility is also high among migrants who emigrate to countries close to their home country, both geographically and culturally. Thus, circular migrants to the Netherlands often originate from EU member states; Canada and the US are also common countries of origin. Migrants from those countries face fewer barriers (such as institutional restrictions), and it is easier for them to assimilate into the Netherlands economy.

Germany

Studies on circular migrants to Germany find similar patterns [4], [8]. Having German or EU citizenship gives migrants the opportunity to move back and forth without restriction. Migrants who enjoyed free labor mobility were the most likely to engage in circular migration, according to data from the comprehensive German Socio-Economic Panel for 1984–1997. About 60% of migrants from former guest worker countries (the guest worker program ended in 1973) who were still in Germany over that period were circular movers. Among them, two-thirds came from other EU countries. Migrants from Greece, Italy, and Spain were particularly mobile, while migrants from Turkey and the former Yugoslavia, who as citizens of non-EU countries were unable to re-enter the country easily, were less mobile, exiting fewer times and spending less time outside Germany. This pattern was also observed in Denmark, where migrants from Pakistan and Turkey had the lowest levels of return migration [7].

Among the studied migrants to Germany, circular migrants were mostly middle-aged and free of close family ties. Migrants without family ties, with low levels of education, who owned homes in Germany, or who had spouses still living in Germany, were most likely to engage in circular migration. For them, seasonal and non-seasonal low-wage labor in other countries provided the main motivation for migrating. Higher-skilled circular movers were more likely to migrate because of educational opportunities, employment transfers, and intra-company transfers [4], [8].

Immigration restrictions can have negative outcomes

A common finding for many countries is that imposing immigration restrictions often has the opposite outcome (more or different migrants) to that intended (fewer or other migrants). If circular migration is allowed to flow without undue impediments, people will migrate for jobs in other countries where the economy is booming and jobs are plentiful. Likewise, they will leave when opportunities become less promising (during recessions or because of falling seasonal employment) or if they have achieved their economic objectives.

Imposing restrictions on immigration through legal measures or tightened border controls that aim to reduce the number of immigrants residing in or entering the country can instead increase the number of immigrants who stay in the country. Tighter immigration restrictions can also intensify immigrants’ efforts to enter the country illegally: If it is difficult to enter legally, workers who are highly motivated by push or pull factors will come illegally. Once in the country, workers who want to leave will tend to stay or stay longer because returning is so difficult.

As a result, return migration home and onward migration to other countries collapse. Would-be circular migrants who cannot easily move in and out of the host country are also more likely to bring family members with them when they migrate, since migrants can no longer be sure that they will be able to return home to see their family. In this way, the suppression of circular labor migration flows often results in a larger and transformed migrant population—and increases the likelihood of unemployment in the receiving community. Not surprisingly, the social burden of this transformation also increases.

In contrast, free mobility and the option to return to the host country—for instance, guaranteed by citizenship rights (dual citizenship) or residence permits—encourage circularity. In Germany, for example, the acquisition of German citizenship has not resulted in prolonged stays by naturalized citizens. In fact, the opposite effect is observed. Because immigrants who become naturalized can return to Germany whenever they want, they can search for and accept the best jobs on offer—whether in the home country or some other country [5]. Dual citizenship and permissive migration agreements between countries can promote circular migration, to the benefit of all parties.

Examples of immigration restrictions that have backfired

United States

Under the so-called Bracero program of free labor mobility that began in 1942, workers from Mexico, mainly men, could travel into three US states along the border for temporary jobs—working primarily for growers in California and agricultural employers in Texas [1]. Immigrants relied heavily on social networks that connected workers in Mexico with employers in the US. Although the program was an effective system of circular labor migration based on temporary work intentions, it was officially terminated in 1964. As a result (and due to other restrictive immigration and border policies), Mexican families began settling permanently throughout the US.

Furthermore, data from the Mexican Migration Project—a study that surveyed Mexicans on both sides of the border—have shown that the massive and costly increase in border enforcement had little effect on the likelihood of initiating undocumented migration. On the contrary, return migration fell because militarization of the border increased the costs and risks for Mexican migrants, so that they stayed longer once they managed to cross the border.

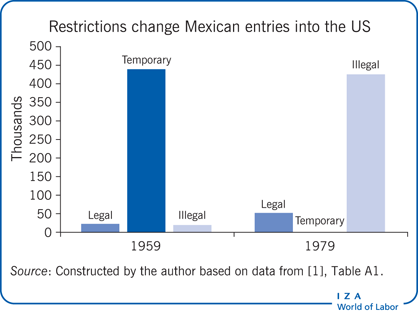

Under the Bracero program, nearly 440,000 Mexicans entered the US on a temporary entry basis in 1959, 23,000 more entered legally under other visas, and 20,000 entered illegally (see Figure 1). At the time the Bracero program was ended in 1964, other work restrictions and border controls were introduced, changing the situation dramatically. By 1979, the number of illegal, undocumented entrants soared to 427,000, and the number of legal immigrants rose to about 53,000. The number of temporary workers slowed to a trickle—just 1,725 people. Thus, barriers installed to reduce labor migration from Mexico to the US backfired, transforming a successful temporary migration scheme into a flow of largely the same number of migrants, but this time migrants who were undocumented and who tended to become permanent residents in the US [1].

Spain

With the economic boom of the 1990s, Spain became a major immigration destination for seasonal agricultural workers from North Africa and cyclical construction workers from Latin America [9]. Spain experimented with several circular migration programs, but after 2004 it began implementing restrictive measures—stricter immigration and asylum policies, tighter border controls, and immigrant quotas. These restrictions failed to stop the immigration flows. Instead, they resulted in increased illegal overstaying of visas and irregular entry, shifting immigration routes, and more dangerous migration. (Illegal entry was a much smaller problem than illegal overstaying, but it attracted much more attention in the media.) As a consequence of tighter border enforcement, African immigration routes shifted—from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Canary Islands, and from Morocco to Mauritania and Senegal—and immigration became increasingly costly and risky, exposing migrants to ruthless smugglers and organizations engaged in human trafficking.

Germany: The end of the guest worker program following the 1973 oil crisis

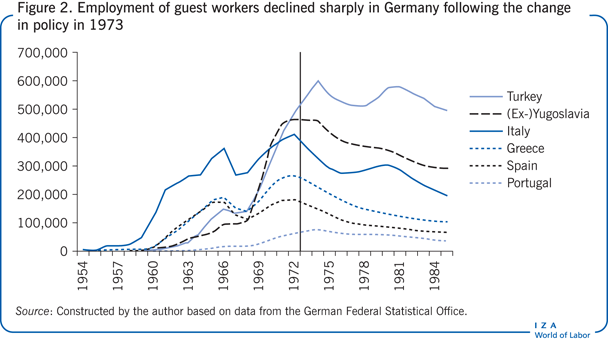

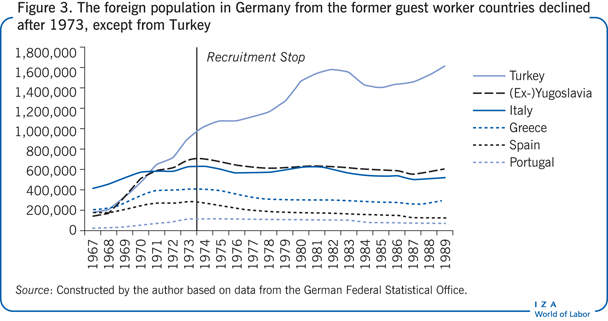

Due to labor market shortages and rapid economic growth in the 1950s and 1960s, Germany and several other Western European countries actively recruited low-skilled laborers from southern Europe. Migrants from Turkey, Yugoslavia, Italy, Greece, Spain, and Portugal flocked into Germany. Following the economic downturn after the 1973 oil crisis, however, Germany ended the recruitment of guest workers and provided economic incentives to encourage workers to return to their home countries [2].

For all but Turkish nationals, the stocks of guest workers declined (see Figure 2). For example, migration into Germany from Greece, Spain, and Portugal—all countries whose citizens could move at some time freely among member countries—virtually stopped. But for Turkish workers, who did not have free labor mobility, migration followed a cyclical pattern, while the stock of Turkish workers remained constant. At the same time, the total stock of all foreign populations declined while the stock of the Turkish population rose substantially. Without sufficient labor demand and with free labor mobility, net immigration declined. It did not decline, however, in cases where severe mobility restrictions were in place, as was the case for Turkish migrants (see Figure 3).

For the Turkish population, permanent settlement and family-based immigration became common. Workers who lost employment did not move home, despite four rounds of financial incentives to return home offered by the German government, and a shrinking share of the population remained employed. Social tensions increased due to weak or absent social and economic integration policies. Hence, the policy backfired in the case of the Turkish community. With a more liberal migration policy, more Turkish migrants would have gone home.

Germany: Failure to benefit from the migration flows following the EU enlargement in 2004 and 2007

The EU enlargements of 2004 and 2007 added eight new member countries and created a new generation of circular labor migrants, largely from Poland. Germany (and Austria) opted against opening its borders to the free flow of workers from the new member states for a seven-year transition period [10]. Fears of mass migration, “welfare tourism,” and displacement effects in the labor market kept Germany’s borders closed—but not without negative repercussions [6].

The best-qualified workers from the new member states went to other EU countries with more open immigration policies. Skilled workers from Poland, for example, migrated to the UK and Ireland—countries that, unlike Germany and Austria, did not restrict immigration. Meanwhile, Germany received an influx of less-qualified workers from EU-8 countries under legal exceptions (for self-employment, for example), as well as increasing numbers of illegal immigrants, counteracting Germany’s protective immigration politics. The presence of these less-skilled workers had a deleterious effect on the other non-EU migrants already living in Germany [6].

Once again, restrictive immigration policies backfired and led to an outcome the opposite of that intended by policymakers. Germany’s closed-door policy not only failed to attract much needed high-skilled workers but was also unable to prevent the inflow of low-skilled immigrants [6].

Limitations and gaps

Circular migration is not a new phenomenon. But because it is difficult to measure, its implications have long been overlooked. Empirical studies on circular migration are rare because suitable data are scarce. National statistical offices generally do not standardize their data, and there is no systematic tracking of migrants’ movements worldwide through an appropriate matching of the national data. In addition, it is almost impossible to observe migration decisions over a lifetime, as would be desirable for studying circular migration. To better understand the global dimensions of circular migration, panel data are needed that can provide information on workers across time and space.

There is also little experience with functioning circular migration policy regimes and little knowledge about how circular migrants interact with diaspora populations and how they affect transfers of knowledge, capital, and goods and services between receiving and sending countries.

Summary and policy advice

Circular migration has received increasing attention recently in the context of labor mobility policies. Circular labor migration is often associated with a range of economic and social benefits for migrants and for both receiving and sending countries. It is practiced most commonly by young, low-skilled men without dependents for whom the only other option is frequently disadvantageous job offers in their home country. Circular migration offers considerable potential for skilled migrants as well.

Policies that restrict immigration, increase border protection, or force migrants to return home have often failed to curtail immigration and have even backfired. Consequences have included rising illegal migration, reduced return migration, increased family migration, and a lower attachment of migrants to the labor market in the host country. Policies that make it easy for migrants to move freely back and forth between home and host countries—with workers basing their migration decisions on labor market conditions at home and abroad—are the best way to avoid the adverse labor market outcomes and social effects associated with restrictive immigration policies. Establishing a well-defined right for migrants to move freely between home and host countries, by enabling circular migration, is essential to a successful immigration policy. Supportive instruments include dual citizenship, permanent residence permits, and liberal immigration agreements between countries.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks anonymous referees, the IZA World of Labor editors, as well as Amelie F. Constant, Olga Nottmeyer, and Ulf Rinne for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. A handbook article on circular migration contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this essay as a background paper [6].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Klaus F. Zimmermann