Elevator pitch

The youth population bulge is often mentioned in discussions of youth unemployment and unrest in developing countries. But the youth share of the population has fallen rapidly in recent decades in most countries, and is projected to continue to fall. Evidence on the link between youth bulges and youth unemployment is mixed. It should not be assumed that declines in the relative size of the youth population will translate into falling youth unemployment without further policy measures to improve the youth labor market.

Key findings

Pros

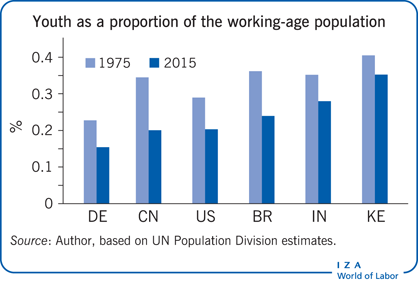

In most developing countries the youth share of the working-age population is now substantially lower than 40 years ago.

Growth of the youth population in most middleincome countries is zero or negative.

The youth share of the working-age population is much lower in high-income than in low-income countries, but youth unemployment is not lower.

The relative size of the youth population has declined in recent decades in high- and low-income countries, but youth unemployment has not.

Countries in the Middle East and North Africa are not experiencing dramatic youth population bulges, so that is unlikely to be a major factor in high youth unemployment or political unrest.

Cons

Many poor countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, continue to have high growth rates of the youth population.

High youth growth rates are projected to continue in sub-Saharan Africa for several more decades, rising by 3.9 million a year and reaching 5.2 million a year over 2025–2030.

Most of the literature finds that larger youth cohorts in high-income countries have worse labor market outcomes.

More recent data confirm that larger youth cohorts have worse labor market outcomes in high-income countries, though the evidence for developing countries is weak or mixed.