Elevator pitch

Policy toward asylum-seekers has been controversial. Since the late 1990s, the EU has been developing a Common European Asylum System, but without clearly identifying the basis for cooperation. Providing a safe haven for refugees can be seen as a public good and this provides the rationale for policy coordination between governments. But where the volume of applications differs widely across countries, policy harmonization is not sufficient. Burden-sharing measures are needed as well, in order to achieve an optimal distribution of refugees across member states. Such policies are economically desirable and are more politically feasible than is sometimes believed.

Key findings

Pros

Viewing refugees as a public good provides a basis for cooperation among countries.

International cooperation can enable better outcomes for refugees and for host country populations if the policies are appropriate.

Large strides have been made in developing the EU’s Common European Asylum System.

Some foundations have been laid for the development of a truly EU-wide policy that focuses on the distribution of refugees.

Public opinion is more supportive of supra-national policies than is often believed.

Cons

Policy harmonization between EU countries is not sufficient to gain the full benefits of cooperation on asylum policies.

Deeper integration of policies would be required to ensure an appropriate distribution of refugees.

Loss of national control of asylum policy may present political challenges for member states.

Closer cooperation between developed countries is only really possible within the framework of the EU.

Deeper policy integration, while helpful, would have only a small impact on the world refugee problem.

Author's main message

Offering a safe haven for refugees can be viewed as a public good, and this provides a basis for cooperation on asylum policies across EU countries. The Common European Asylum System has harmonized policies, but harmonization has not improved the severe imbalance in the distribution of asylum applications across countries. The most realistic option would be to first set the central policy to obtain the optimal number for all the countries together and then to reallocate asylum-seekers to obtain the “right” number for each country. The deeper policy integration that this would require is more feasible than is sometimes believed.

Motivation

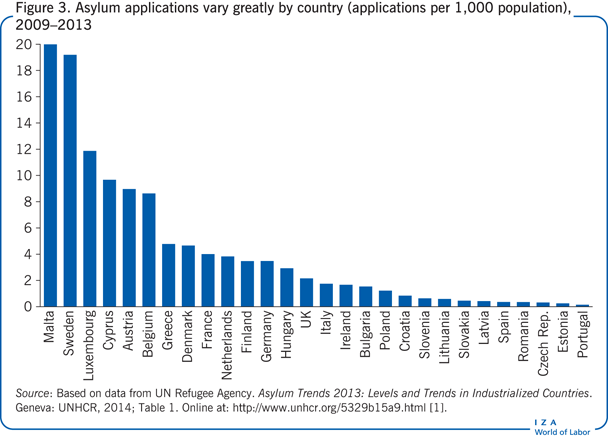

Since 1989, more than 12 million applicants for asylum have arrived in developed countries, an average of nearly half a million a year (Figure 1). The number has ebbed and flowed in response to periodic surges in civil war and human rights abuses in low- and middle-income countries. Flows peaked in the early 1990s, largely as a result of the turmoil in eastern and central Europe following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union; and again in the early 2000s, following the breakup of Yugoslavia. The Arab Spring of 2011 launched a third wave, shifting the locus of origin and transit countries.

The 25-year surge in asylum applications has provoked widespread controversy, and national governments have responded with ever tighter restrictions in what some have seen as a policy backlash. The EU has become an increasingly important player as it has developed the Common European Asylum System. This paper outlines a framework in which to evaluate those policies. It focuses on the deterrent effects of tougher asylum policies and on the rationale for cooperation between European host countries. Drawing on existing studies, it argues that policy harmonization is not sufficient and that some form of burden-sharing is needed as well.

Discussion of pros and cons

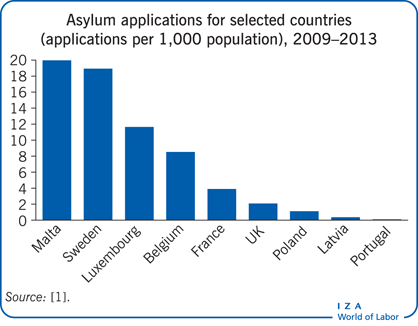

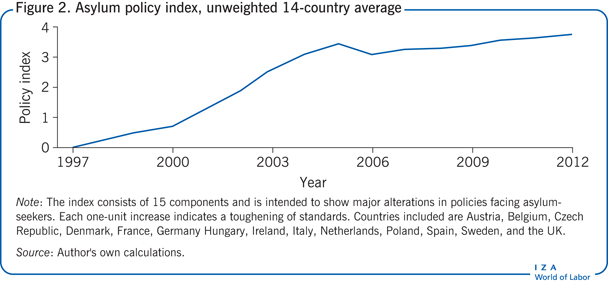

Since 1989, the overwhelming majority of asylum-seekers to the developed world have claimed asylum in Europe (77%), mostly in the pre-2004 member states of the EU (71%). More than half of applications in Europe were received by three countries: Germany (28%), the UK (12%), and France (11%). But the distribution of asylum claims per capita of the resident population looks very different. The distribution has been very uneven in recent years, with particularly high rates in Malta and Sweden but also in Luxembourg, Cyprus, Austria, and Belgium. At the other end of the spectrum, rates are very low for the Iberian and Baltic countries.

Most asylum claims are “spontaneous” applications—they are made by individuals or families arriving in the country of asylum or at the border. An unknown but large proportion of these seekers arrives illegally. Once an asylum claim is lodged, it enters an adjudication process to determine whether the applicant is a genuine refugee. Applicants who gain refugee status are allowed to stay and normally to settle permanently in the receiving country. Those whose claims are rejected are required to leave, although many disappear from sight and stay on as illegal immigrants.

Asylum policies and their effects

Asylum policies have changed substantially since the 1990s. A principal motivation behind these policy changes has been to tighten the rules in order to control what in some periods has seemed like an ever-rising tide of applications. Asylum policy is multi-faceted, but the individual measures can be divided into three broad categories. One relates to policies that limit access to the receiving country’s asylum procedures, mainly by preventing potential asylum-seekers from reaching the country. A second relates to the status determination procedure and the rules governing whether an applicant gains refugee status. A third includes policies relating to welfare conditions faced by asylum applicants during and immediately after processing.

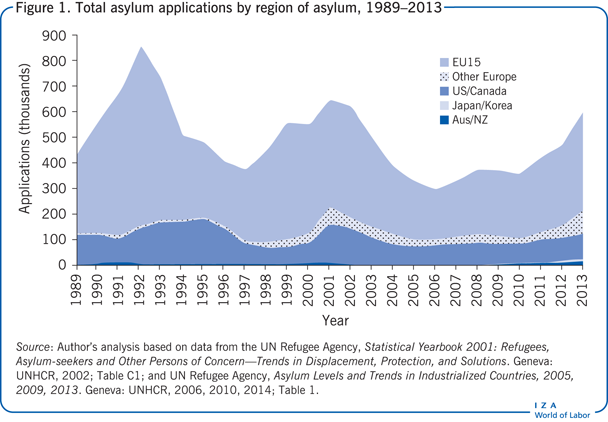

Several attempts have been made to capture the stance of asylum policies for the main receiving countries [2], [3]. The idea is to form an overall index based on changes in a diverse range of laws, regulations, and practices relating to asylum. One such index, shown in Figure 2, is an unweighted average for 14 European countries, comprising 15 components, each of which increases by one unit when policy becomes markedly tougher for asylum-seekers. The index is intended to reflect changes in policy that result in major alterations in the conditions facing a substantial proportion of asylum-seekers. Such judgments are inevitably subjective, but they are based on contemporary reports by country experts rather than on ex-post evaluations of the outcomes of policy change. Examples include implementing substantial changes in visa policies, fast-tracking the processing of “manifestly unfounded” claims, and providing subsistence only at reception centers.

Starting from zero at the beginning of 1997, the index shows a steep rise from 2000 to 2005, and then a mild increase in toughness after 2006. The steep rise in the early 2000s represents a considerable tightening of policy, which was partially a response to the surge in asylum claims from 1997 to 2002 (see Figure 1). The more gentle increase after 2006 probably reflects the reduced number of applications after 2004, which weakened policy imperatives. But it may also reflect the growing involvement of the EU in setting policy, as discussed below.

One widely debated question is whether such policies actually deter asylum applications. The evidence suggests that they do [2], [3], [4]. Policies that matter most are those relating to border control and the process for determining refugee status. For 19 OECD countries for which estimates are available, the effect of the dramatic tightening of access to territory and tougher processing policies between 2001 and 2006 was to reduce annual asylum claims by 108,000 [3]. These effects account for a 19% decline from the 2001 level and for 33% of the decline in total applications from 2001 to 2006. Thus, policy has a significant deterrent effect, but conditions in source countries matter even more.

The case for cooperation over asylum policies

In democratic societies, immigration policies are often viewed from the perspective of whether they serve the interests of host populations, either specific individuals, as in the case of family reunification, or the wider economy, as in the case of skill-selective labor migration. But asylum is different: refugees are admitted on the grounds of the benefit to themselves rather than to others in the host society. This can be seen in the basic criterion for refugee status (from Article 1 of the 1951 Refugee Convention), which is a “well-founded fear of persecution.”

The benefit to the host society of providing a safe haven for refugees is to satisfy basic humanitarian motives. The benefit to one individual does not reduce the value to others, and individuals cannot be effectively excluded from benefitting. Thus, because the benefit is non-rivalrous and non-excludable, refugees can be viewed as a public good. If one country provides sanctuary for those fleeing persecution, then residents of another country benefit from the knowledge that these refugees have found safety. But the costs fall only on the country providing refuge. If each country sets its asylum policy independently, that policy will fail to take account of the benefits flowing to the residents of other countries. In such a case, the public good will be under-provided. A benevolent social planner would set policies that take the public-good spillover into account.

In a setting where the demand for asylum (the number of applicants for asylum) differs across potential receiving countries (Figure 3), policies set non-cooperatively will also differ. Countries receiving a disproportionate number of claims will have tougher policies in order to limit the number of such refugees to the desired level. If the policies of different countries were to be set by a single benevolent social planner, more refugees would be admitted, but policies would still differ across countries because they face different levels of demand. If, on the other hand, a central authority were to impose the same policy for all countries, then relative to the social optimum, some countries would have too many refugees and some would have too few. Thus the overall social optimum would not be reached [5].

If a centralized policy seeks to set common standards for the adjudication of asylum claims, for border controls, and for the treatment of asylum-seekers, as in the case of the Common European Asylum System, then some other mechanism must be found to reach the social optimum. One possibility would be to establish a common fund to compensate countries hosting a disproportionate number of asylum refugees. Another possibility would be to first set the central policy to obtain what would be the optimal number for all countries as a group and then to reallocate the cases to obtain the “right” number for each country.

Development of the Common European Asylum System

Cooperation between EU countries over asylum policies dates from the 1990s, largely in response to the surge in asylum applications illustrated in Figure 1. The 1990 Dublin Convention provided a method for determining which country should deal with an asylum claim, in order to prevent “asylum shopping.” Normally this is the country of first entry. Resolutions made at a ministerial meeting in London in 1992 included a measure of agreement on designating as “safe” certain countries of origin and of transit, with the idea that applicants from such countries could be safely rejected. A number of other measures were agreed in the 1990s, on issues such as designating some countries as “safe”. But for the most part, asylum policies were set by national governments, with very little direct coordination. The concurrent tightening of policies by individual countries during the 1990s largely reflected the Europe-wide surge in asylum applications [2].

The development of policy at the EU level began with the Amsterdam Treaty in 1999, which passed the initiative for policy formation to the European Commission after 2002. Meanwhile, the European Council meeting at Tampere in 1999 laid out plans to develop the Common European Asylum System. Based on “full and inclusive” application of the 1951 Refugee Convention, these plans focused on harmonizing key areas of asylum policy. They included a revised version of the Dublin Regulation, now linked to the EURODAC fingerprint database. There were also directives covering the criteria for granting asylum (the Qualification Directive) as well as the procedures to be used in adjudicating claims (the Asylum Procedures Directive) and the rights and conditions afforded to asylum-seekers (the Reception Conditions Directive). These directives laid down only minimum standards, and harmonization across the full range of procedures was far from complete.

In the aftermath of the Kosovo crisis in the late 1990s, some steps were taken toward sharing responsibilities (burden-sharing). The European Refugee Fund, established in 2000, provided a common financial pool to support projects for integrating refugees into the host country and to provide resources in the event of a mass influx of refugees. Although this was expanded to provide for initiatives on reception and return of asylum-seekers, it remained small in relation to the total numbers of refugees. Another measure was the Temporary Protection Directive of 2001, whose purpose was to relocate refugees from countries under exceptional pressure in the event of a mass influx. While the Temporary Protection Directive provides some basis for burden-sharing, it lacks a formal triggering mechanism or a formula for redistribution. Not surprisingly, it has never been invoked.

The next stage in the development of the Common European Asylum System was the Hague Programme implemented in 2004–2010, which deepened integration in a number of areas. These included the establishment in 2005 of the FRONTEX agency to integrate and standardize border control and surveillance. There was also further harmonization of the rules and procedures for determining refugee status determination. Programs for integrating refugees into the host country were also expanded with enhanced financial support from the European Refugee Fund.

In 2010, the European Asylum Support Office was established in Malta with the aim of disseminating best-practice methods and supporting states facing exceptional asylum pressures. While the office was also expected to assist in the relocation of recognized refugees, that is to be done only on an agreed basis between member states and with the consent of the individuals concerned. In addition, the Dublin Regulation was further revised to take account (at least in principle) of the pressures faced by different countries; the European Refugee Fund was augmented and its name changed to the Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund; and the key directives were further revised and upgraded.

The Common European Asylum System and burden-sharing

All these measures represent considerable progress in harmonizing the rules, standards, and procedures for granting asylum. Nevertheless, application of the directives and regulations remains uneven across the EU. Much less progress has been made in developing effective burden-sharing policies. What this means is that if all countries share the same asylum rules, demand for asylum will still differ across countries and so will the distribution of recognized refugees. Thus, the current arrangements cannot reach the social optimum described above. Starting from a position where differences in policy reflected differences in the demand for asylum, convergence in policies could potentially lead to even greater divergence in refugee burdens, as seems to have happened between 1996–2000 and 2006–2010.

Not surprisingly, there have been ongoing discussions of burden-sharing mechanisms starting as far back as the 1990s. Proposed formulas have been based on estimates of countries’ capacity to host refugees, usually calibrated on some combination of population, population density, and GDP per capita. One study for the European Commission using asylum applications in 2008 found that equalizing the burden would require transferring between one-third and two-fifths of all applicants [6]. A study for the European Parliament estimated the need for more modest transfers of 15–18% of the total inflow in 2007 [7]. It considered the possibility of financial compensation to countries receiving excess numbers of asylum-seekers but concluded that this would involve too vast an expansion of the European Refugee Fund. The study concluded that a policy of redistribution “is the only mechanism that is likely to have a real impact on the distribution of asylum costs and responsibilities across member states.”

Supposing that there was sufficient political will to pursue some element of redistribution of asylum applications across EU countries, the question becomes how this could be realized. It would require much greater centralization of asylum policy. Essentially, responsibility for adjudicating asylum claims and assigning successful applicants to different EU countries would pass from member states to the EU. That would require a substantial upgrading of the EU’s authority and its capacity to implement policy. But some of the building blocks are already in place. One of these is the European Asylum Support Office, a central administration whose functions would need to be substantially expanded. At present it has a mandate to support, assist, and coordinate but not to direct.

Another is the Temporary Protection Directive, which was issued in the wake of the Kosovo crisis to provide protection in the event of a mass influx and to promote a “balance of efforts between Member States.” This directive needs to be revived from its moribund state by investing it with the power to direct at times of crisis. The lack of a formal triggering mechanism has meant that this directive has never been activated. Yet as the pressure of refugee numbers mounted in Malta after 2009, a modest reallocation program (600 cases) was initiated. Member states participated on a voluntary basis, and the operation was conducted with the involvement of the International Organization for Migration and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

Perhaps most in need of reform is the Dublin Regulation. After two revisions, it still works on the principle that an asylum claim should be dealt with by only one state, usually the first state of entry. Mechanisms have been developed to determine when a member state should “take back” or “take charge” of a particular asylum case. As has long been recognized, this means that in some instances asylum cases are referred to countries that are already under pressure. A better idea would be to scrap the current regulation and establish a mechanism for reallocating asylum claims in a way that improves rather than worsens the distribution.

But, of course, change is not that simple. Critics argue that compulsory reallocation of asylum-seekers could violate human rights and that separating the processing of applicants and the resettlement of refugees between countries would multiply the cost. Yet such systems have long operated within countries. In Germany, for example, refugees are allocated between (and then within) the country’s 16 states. Nevertheless, it might reduce costs (and improve incentives) to reallocate applicants before rather than after processing. Others suggest that the sheer scale of transfers makes this infeasible. One solution would be to redirect asylum claims only when the number of applications to a particular country exceeded a critical threshold, rather than trying to match the numbers exactly to a distribution key. Another would be to introduce a more market-based mechanism such as tradable admissions quotas and combine it with a mechanism to match transferees to the preferences of host countries [8].

Political feasibility

A major stumbling block in developing the Common European Asylum System is the perception that national electorates are, to various degrees, opposed to liberalizing asylum rules and unambiguously prefer tougher rules and fewer refugees. One reason is that politicians and the media have managed to conflate the term “asylum-seeker” with terms like “illegal immigrant” and “welfare scrounger.” In 2002 (and not subsequently), the European Social Survey asked respondents whether they agreed with the statement: “The [national] government should be generous in judging applications for refugee status.” On average across 19 EU countries, one-third of respondents agreed with the statement, while two-fifths disagreed. So despite that being a time of very high asylum claims (see Figure 1), the balance of opinion was not overwhelmingly negative. Not surprisingly, opinion was more negative the higher the number of applications per capita [9].

The European Social Survey also asked respondents (in 2002 only) at which political level decision-making on immigration and refugee policy should occur: international, European, national, or regional/local. On average across the 19 countries, 58% selected the international or European level [9]. This finding, echoed in surveys such as the World Values Survey and Transatlantic Trends, suggests that there is far more support for supranational policy making than is often believed.

Nevertheless, there are concerns about whether EU member governments would see it as in their interest to participate in such a scheme, which could leave some countries worse off than in the absence of cooperation [10]. Another concern is that the welfare benefits of cooperation might be undermined by countries strategically choosing an unduly negative bargaining stance [11]. However, these analyses focus on situations in which representatives of national governments negotiate over policy settings that would (and should) differ by country. This contrasts with the situation where policy-setting is ceded to a supranational body over which individual governments have little direct control.

That leaves the question of whether EU institutions would craft an asylum policy that comes closer to the social optimum than the current situation. There are some reasons to think that they would. The EU has successfully established a bulwark against restrictive policy moves in some countries [12]. A strong pro-refugee tendency is reflected in recent decisions of the European Court of Justice and in the inauguration in 2007 of the Fundamental Rights Agency. Yet there are serious threats to building a more integrated and enlightened asylum system. One is that recent trends in European Parliament elections do not seem favorable to constructive reforms in asylum policy, notwithstanding the increased accountability introduced by the inception of co-decision-making between the European Council and the European Parliament.

Limitations and gaps

There has been considerable progress on cooperation over asylum policies within the EU. But the underlying basis for cooperation remains unclear. Viewing refugees as a public good provides a clear rationale for cooperation and suggests that refugee places will be under-provided in the absence of jointly determined policy. But the value of public goods is hard to establish, and all the more so in the case of refugees, an issue over which opinions differ widely. An unresolved question is exactly how much value the citizens of one country place on refugees that are given a safe haven in another country.

For reasons outlined above, the distribution across countries of asylum applicants and refugees is important. When that distribution is severely imbalanced, the total number of refugees that are given protection is likely to be sub-optimal. The harmonization of asylum policies and the Dublin Regulation have exacerbated these imbalances. Although national governments have adopted internal distribution mechanisms, it would require a step-change to implement such a mechanism across EU countries. This would require a further transfer of power to the EU, something likely to be seen as yet another threat to national sovereignty.

Although the arguments presented here do not apply exclusively to the EU, the scope for wider application is limited. Incorporating countries like Norway and Switzerland, and perhaps a few others, into the Common European Asylum System is one possibility. There has been some cooperation in response to crises between Canada and the US and between Australia and New Zealand. But these countries already have large resettlement programs. The scope for wider cooperation within these regions is limited because of big gaps in development and the lack of EU-style regional frameworks. In the case of Australia and New Zealand, many of their nearest neighbors are not even signatories to the Refugee Convention.

The UNHCR estimates that 80% of the 12 million refugees in the world are in low- and middle-income countries. They are often stranded in dire conditions, sometimes for protracted periods, in makeshift camps across the border from their country of origin. Resettlement and independent asylum-seeking to rich countries make very small inroads on the numbers in these seemingly intractable situations. Deeper cooperation on asylum between rich countries would help, but it would not solve the larger refugee problem.

For more than a decade, the UNHCR has been urging greater cooperation between rich and poor countries, but it has been unable to broker any firm agreement on burden-sharing [13]. There is simply too little alignment of interests to support any sort of grand bargain. Direct aid and assistance seem more realistic goals, especially to countries like Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, Pakistan, and South Sudan, where the numbers of refugees far exceed local capacity. A shift in focus toward the regional level for facilitating refugee integration, resettlement, and return is more realistic but remains grossly underfunded.

Summary and policy advice

The Common European Asylum Policy has come a long way and has achieved some successes. The focus has been on the harmonization of border controls, the process of determining refugee status, and the conditions faced by asylum-seekers. More attention needs to be given to creating a more even distribution of asylum claims across countries in order to reach the socially optimum number. One possibility would be to beef up the existing Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund to provide greater compensation to countries that receive a disproportionate number of asylum-seekers. A much more realistic option would be to reallocate some proportion of asylum claims across countries. This would involve abolishing the existing Dublin Regulation and substituting an alternative system that improves the distribution. In order to limit the scale of transfers, claims could be redirected only when the applications to a country exceed a critical threshold rather than aiming for exact equalization. An alternative would be to introduce tradable admissions quotas and combine this with a mechanism to match transferees to receiving countries. Some of the building blocks for a redistribution system are in place, but further centralization of policy is required. While there may be political impediments, public opinion is more supportive than is sometimes believed.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for helpful suggestions on an earlier draft. Previous work of the author contains more background references for the material presented here and has been used throughout this paper [4].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Tim Hatton