Elevator pitch

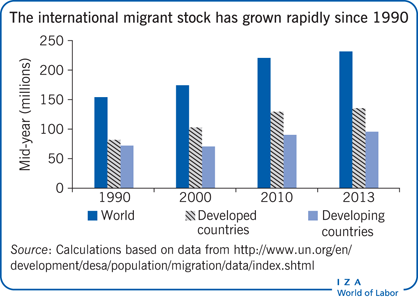

About a billion people worldwide live and work outside their country of birth or outside their region of birth within their own country. Labor migration is conventionally viewed as economically benefiting the family members who are left behind through remittances. However, splitting up families in this way may also have multiple adverse effects on education, health, labor supply response, and social status for family members who do not migrate. Identifying the causal impact of migration on those who are left behind remains a challenging empirical question with inconclusive evidence.

Key findings

Pros

The migration of a family member brings additional income through remittances, which can support household consumption and investment.

This income effect can reduce the need for child labor and increase children’s schooling, notably for girls in developing countries.

Remittances can improve families’ sanitation, health care, and nutrition and fill in for missing formal health insurance in the short term.

Remittances can enable remaining family members to engage in higher-risk, higher-return productive activities.

Where most migrants are men, the bargaining power of women who stay behind may be strengthened.

Cons

The migration of an economically active family member places a heavier burden on those who stay behind, who must make up for the lost employment and spend more time on household chores.

The absence of the main caregiver can increase children’s probability of dropping out of school and delay school progression.

Disrupted family life can lead to poor diets and increased psychological problems.

Migration may reduce incentives for education when perceived future returns to education are low because of expectations of migration.

Migration can reduce labor force participation for family members left behind, especially for women.