Elevator pitch

In Europe, about one in eight people of working age report having a disability; that is, a long-term limiting health condition. Despite the introduction of a range of legislative and policy initiatives designed to eliminate discrimination and facilitate retention of and entry into work, disability is associated with substantial and enduring labor market disadvantage in many countries. Identifying the reasons for this is complex, but critical to determine effective policy solutions that reduce the extent, and social and economic costs, of disability-related disadvantage.

Key findings

Pros

There is a growing international body of evidence exploring the labor market experience of disabled individuals.

Parts of the raw gaps in labor market indicators by disability are explained by factors other than disability, including age and educational attainment.

There is growing use of experimental methods that attempt to identify labor market discrimination against disabled people in hiring.

The literature extends to consider evidence from developing countries.

Longitudinal evidence highlights that for many individuals who experience disability onset, it is not permanent.

Cons

There are limitations of using self-reported information on disability status from survey data, particularly in comparisons across countries.

There is consistent evidence that disability is associated with substantial labor market disadvantage, particularly in terms of employment.

Longitudinal analysis provides evidence of a likely causal influence of disability on labor market outcomes.

Disability may affect work-related productivity and preferences, making it particularly difficult to identify discrimination using survey data.

There is no consistent evidence that anti-discrimination legislation has improved the labor market outcomes of disabled individuals.

Author's main message

The prevalence of disability, combined with its substantial labor market disadvantage, makes the design of effective policy critical for reducing its negative social and economic consequences. However, this process is complicated by difficulties in measuring disability and in distinguishing its influence on work-related productivity and preferences from employer discrimination. Recognizing that the labor market impact of disability varies by type, severity, and duration may nevertheless facilitate a more tailored and flexible approach to policy, which provides the necessary incentives and support to work for those who are able.

Motivation

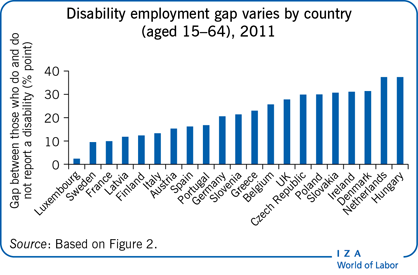

Across European countries, about one in eight working-age individuals (aged 15–64) report disability as defined by a long-term health problem (at least six months) and a basic activity limitation; in some countries, such as France and Finland, this proportion rises to one in five (Figure 1).

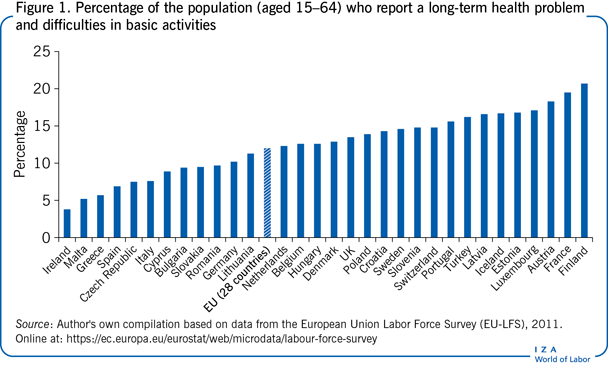

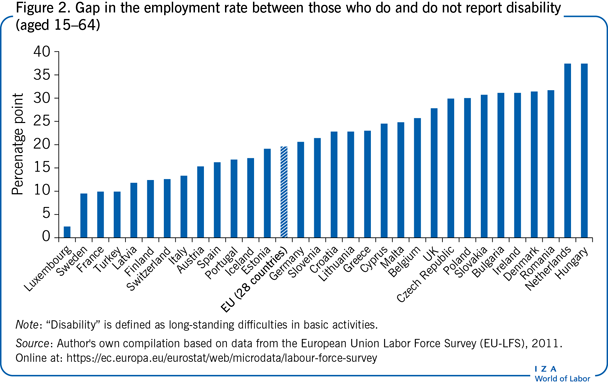

There is also widespread evidence of a substantial and enduring disability employment gap, which refers to the percentage point difference in the employment rate between those who do and do not report disability. When disability is defined as limitations in basic activities, the average employment gap across Europe is about 20 percentage points, reflecting an employment rate among disabled individuals of 47% as compared to 67% among those not disabled. As shown in Figure 2, the gap varies from about ten percentage points in Sweden and France to nearly 40 percentage points in the Netherlands and Hungary. There is an important link between the prevalence rate (i.e. the percentage of people reporting disability) and the associated relative employment disadvantage experienced by disabled people; tighter definitions of disability, which typically exclude those with milder disabilities, are accompanied by more substantial estimates of disadvantage. Indeed, in Europe, the corresponding employment gap relating to disability when it is defined as limitations with work (as opposed to basic activities) is larger, at nearly 30 percentage points.

Discussion of pros and cons

Measuring disability

The availability of comparable international survey data such as that presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2 is limited and, while it appears to provide opportunities for cross-country analysis, there are important measurement issues involved. The magnitude and nature of international variation, particularly in terms of disability prevalence, raise important concerns about the extent to which self-reported disability, which depends on the social, economic and policy context, is comparable across countries [1]. Indeed, the incentives to self-report disability may depend on social acceptability and its financial implications, which themselves are likely to stem from country-specific institutional features, such as the welfare system and anti-discrimination legislation. Nevertheless, some common patterns have been observed: rates of disability are typically higher in northern than in southern Europe, these rates increase with age and decrease with more formal educational qualifications. Across the EU, for example, the percentage of the population reporting disability among those aged 55–64 (26%) is eight times higher than among those aged 15–24 (3%).

The majority of evidence used in this article relies on self-reported measures of disability, which are now routinely available from national survey data across many developed countries. They have, however, been subject to a number of criticisms, and studies have sought to explore their validity using more objective information such as activity restrictions arising from functional limitations. But these objective measures of health are also likely to suffer from measurement error as the concept of disability, that is the outcome of the interaction between health and environmental barriers, will itself depend on the individual's social and economic environment. As such, rather than using an alternative measure in place of self-reported information, studies have examined how self-reported disability varies compared to “true” disability that is, for example, constructed from objective health measures or receipt of disability benefits. The results are, however, mixed and inconclusive, with studies finding evidence both for and against the use of self-reported data on disability.

The analysis of a subset of disabled individuals who receive disability welfare payments forms a largely separate strand of literature. While this is arguably a more objective measure of disability, in the sense that recipients typically have to meet specified medical criteria, eligibility for, and therefore receipt of benefits depends on the nature of the scheme. Indeed, the majority of these schemes are designed as a form of income replacement, and therefore tend to impose intentional and substantial restrictions on “permitted employment.” This design feature limits the usefulness of disability defined in relation to welfare benefit in analyzing individual labor market outcomes. Nevertheless, cross-country variation in receipt of disability benefits among older workers, which substantially exceeds variation in indicators of objective health, suggests that disability welfare forms a route into early retirement in some countries. Moreover, country-specific studies, such as those based on changing benefit regimes, provide important evidence of a causal relationship between the level of disability benefit and nature of restrictions on permitted employment, and non-participation in the labor market. As such, the design of the disability welfare system is undoubtedly an important contributory factor to the broader self-reported disability-related employment gap.

The nature of disability welfare schemes has attracted increasing attention, at least partially due to significant growth in disability benefit caseloads and the associated financial pressure, particularly in parts of northern Europe, the US, the UK, and Australia. This growth has occurred over a period where objective measures of health have generally been improving and dominant explanations for growth instead relate to the design of the scheme (e.g. relaxation in eligibility requirements and increasing relative generosity), changes in demographics, female labor force participation, and reduced demand for low-skilled workers [2]. Recent reforms of disability benefit systems have tended to contain active strategies to encourage re-engagement with work designed to enhance the (typically low) rate of exit from disability benefits. Tighter medical (among other) eligibility criteria have also been introduced to reduce the inflow of recipients and to better target support to those who are unable to work. While there is recognition of the difficulty associated with attempting to achieve two conflicting goals, that is, providing financial support to those unable to work while at the same time encouraging those who can to retain or re-engage employment, there has been some recent success, at least in terms of reducing caseloads, particularly in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, in considering the broader disability employment gap, it is important to assess the extent to which such reforms have led to continued labor market attachment (or re-attachment) rather than benefit displacement.

Disability, employment, and earnings

The size of the employment gap (Figure 2), combined with its persistence over time and existence across developed countries, has motivated a body of evidence which attempts to identify the drivers of, and trends in, disability labor market inequality. The latter, in particular, has been used to assess the effectiveness of major changes in policy and legislation. This evidence frequently also considers hourly labor market earnings, where the disability gap is often more modest than that relating to employment but, at between 10% and 20% it is nonetheless significant and comparable to pay gaps for other protected characteristics in many countries.

Explanations for the disability-related employment gap vary and include: pre-existing disadvantage, changes in capacity for and ability to work, and changes in preferences for work, such as those arising from changes in the value of leisure and/or eligibility for welfare support. They also include reverse causality, including justification bias; that is, the incentive for those who are out of work to legitimize their situation by subsequently reporting disability. A key issue has, however, been identifying the influence of discrimination or unequal treatment by employers arising from prejudice or imperfect information (whereby the employer uses disability as a signal of low productivity). Studies have attempted to distinguish discrimination from the disadvantage associated with other personal and work-related characteristics using comprehensive survey data. This type of analysis asks to what extent gaps in the raw data reflect disability, per se, rather than other factors, such as age and education, which are correlated with disability. A substantial proportion of both employment and earnings gaps are found to relate to disability, or what is often referred to as being unexplained. In the UK, for example, about 75% of the disability employment gap, and between 50% and 75% of the disability earnings gap, are unexplained by other factors [3], [4].

One limitation of this type of analysis is that it is difficult to control for all the potential differences between disabled and non-disabled people. Factors which are typically not fully observed include the impact of disability on work-related productivity or preferences. As such, the unexplained gap is almost certainly an overestimate of disability discrimination. Studies have attempted to tackle this issue by controlling for functional limitations and/or by using different definitions of disability to identify groups of disabled individuals who are more or less likely to experience discrimination or productivity reductions at work. These studies tend to find that discrimination plays a less important role [3], [4].

Albeit necessarily restricted to specific occupations and disability types, and to labor market hiring, an alternative experimental approach is increasingly being used to explore discrimination in circumstances when disability does not affect productivity in work. In this approach, applications from disabled and non-disabled people with otherwise identical resumes are sent to employers in response to a job advert. The emerging international evidence from countries including the US, Belgium, and Canada suggests that employer response rates are significantly lower for disabled relative to non-disabled applicants, consistent with discrimination [5]. Moreover, several of these studies find no positive impact of government financial support for disabled workers on employer responses, consistent with it having limited impact on hiring.

Studies have also used survey data to evaluate the impact of major changes in legislation which have made discrimination against disabled individuals unlawful, by comparing the outcomes of disabled and non-disabled individuals before and after the introduction of the legislation. Examples of this type of legislation, including the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the US and the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) in the UK, contain two main components: an antidiscrimination element that makes disability discrimination unlawful, and a reasonable adjustment element that requires employers to make changes to the workplace and work practices to prevent a disabled person from being disadvantaged. Although the threat of legal action related to disability discrimination on hiring would be expected to increase the employment of disabled individuals, the anticipated increase in firing costs arising from wrongful termination combined with the costs of accommodation are predicted to act in the opposite direction. It is the latter that is anticipated to dominate and, due to the expected increased costs for employers when hiring disabled individuals, is predicted to reduce demand for disabled workers [6].

Overall, there is little evidence of positive employment effects arising from the introduction of such legislation [6]. Moreover, negative employment effects in the US have been found to vary by firm size and by variations in disability discrimination charges among states in a manner that is consistent with an adverse influence of the ADA [6]. Indeed, when using variation in pre-existing legislation between US states, there is preliminary evidence that it was the introduction of the reasonable accommodation element of the legislation that gave rise to its short-term negative consequences [7]. Nevertheless, these findings have not gone undisputed, with factors other than the ADA—for instance, the economic cycle and changes in the disability welfare regime—put forward as alternative explanations for the decline in the employment rate among disabled individuals in the US.

European countries have tended to employ a range of alternative policies to increase the employment rate of disabled people, including quotas and employer subsidies. Although there have been a number of studies evaluating specific schemes, for example in Austria where there is evidence that a quota scheme which has been accompanied with financial penalties for non-compliance as well as financial support for workplace accommodation and wage subsidies for disabled workers has had a positive effect on the employment of disabled people [8], there remains a lack of consensus about what works.

While the evidence is largely based on data from developed countries there has been increasing academic and policy attention on the issue of disability-related labor market disadvantage internationally, including in India, Vietnam, and South Africa. Despite the additional challenges imposed by the reliability of data on disability in developing countries, recent studies have applied similar methods to explore the scale and nature of the disability employment and pay gaps, and impact of disability-related policy, including in relation to welfare. While this analysis documents considerable variation in the prevalence and impact of disability across developing countries, it confirms that there is an unexplained disability employment gap for males in many developing countries [9].

Disability and the experience of work

Extensions to these original themes within the literature have considered broader labor market outcomes including hours of work and the nature of employment. The concentration of disabled workers in non-standard employment, including part-time and self-employment, raises questions about the extent to which this reflects “push” factors, such as inequality of treatment, or “pull” factors, including the ability to accommodate disability in work. Such analysis has also started to consider the experience of work using subjective measures of skill utilization, job satisfaction, work-related well-being, perceptions of managers, and employee commitment. Relative to their non-disabled counterparts, disabled workers tend to report more negative experiences across a range of in-work outcomes; this trend is evident across several countries including the US, the UK, and Australia [10]. Further, this is not explained by differences in personal characteristics or more objective work-related characteristics, such as hours worked or occupation, and therefore exists, on average, between similar disabled and non-disabled workers in comparable jobs. Understanding the disability gap in work-related perceptions and well-being is not only important in its own right, but is also likely to contribute to the employment and earnings gaps via the impact on the recruitment, retention, and productivity of disabled individuals.

An interesting question, which can be explored using matched employee–employer data, is what role the employer has and what influence specific workplace policies and practices have on this disability disadvantage. While these issues remain underexplored as a consequence of a lack of reliable matched employee–employer data internationally, recent US evidence finds that the disability gap in perceptions disappears in workplaces that are viewed as the most fair among all employees, pointing to the importance of “corporate culture” [10]. Nevertheless, evidence from the UK is less conclusive, with a recent study finding the more negative experience of recession-induced changes in working conditions (including in terms of workload and pay) among disabled employees to be common across workplace equality characteristics [11].

Longitudinal evidence

A major criticism of the literature is the focus on cross-sectional data and associations between variables rather than causal relationships. More recently, longitudinal evidence, which is able to exploit the dynamic nature of disability to track the same individual over time, has been used to identify the disadvantage associated with disability measured relative to the same individual pre-onset (i.e. before that individual became disabled), rather than to a similar non-disabled individual, who may differ in a range of unobserved ways. Among other things, such analysis is able to separate the disadvantage associated with disability onset from pre-existing disadvantage, and is able to use the timing of disability onset relative to the observed disadvantage to rule out reverse causality. It is also able to explore the long-term effects of disability and the extent to which the impact of disability narrows or widens over time. Longitudinal evidence has one further advantage: it is able to identify and distinguish between disadvantage associated with different dynamic patterns of disability, particularly the duration of disability. Indeed, in contrast to common perceptions, analysis of the dynamics of disability highlights that, for many, disability is not permanent.

Although much of the existing longitudinal evidence is based on US data, there have also been important recent contributions in the UK and Australia. Several key findings emerge from this literature. First, there is evidence that disability onset is associated with employment disadvantage relative to the same individual pre-onset, which is consistent with a causal explanation. Further, the dynamics of disability are important: those with chronic disability, which is defined as persisting post-onset, experience greater disadvantage at onset and, in contrast to arguments that individuals adapt, this disadvantage is exacerbated post-onset, consistent with a negative disability duration effect. Finally, self-reported severity is a key driver of the magnitude of disadvantage. For example, relative to other types of disability onset, those who report chronic severe disability experience more than 3.5 times the reduction in annual working hours ten years post-onset [12]. Further, this type of framework has been used to consider the broader impact of disability on well-being, recognizing that the implications of changes in individual labor market status may have a less pronounced impact on household income and/or consumption when there is support within the household or from government welfare. Even after accounting for this, there is evidence of an impact of disability onset on disposable income and consumption expenditure, consistent with a residual impact on well-being [12]. Indeed, recent evidence from the US, the UK, Germany, and Australia which points to a negative impact of disability onset on self-reported life-satisfaction raises interesting questions for policymakers about how social and economic disadvantage should be measured and policy support should be targeted.

The focus on the dynamics of disability has also raised questions about the influence of the timing of onset [13]. It is important to distinguish between those who are disabled at birth or during childhood and those who have already entered the labor market pre-onset because the barriers to employment for these two groups may differ. Among the first group, disability may affect the accumulation of human capital and will precede entry into the labor market, whereas human capital is likely to have been largely determined prior to disability onset among the latter, where the key issue may instead be job retention. Indeed, in this study a distinction is made between general human capital, which is valued equally for disabled and non-disabled individuals (such as formal education or training); healthy human capital (i.e. human capital that cannot be utilized due to disability), which is valued only for non-disabled individuals; and disability human capital, which is valued only for those with a disability (such as learning to use adaptations) [13]. If healthy human capital increases with age, those with age-onset disability will face more severe disadvantage. Further, those who are disabled at a younger age should have a greater incentive to invest in disability-specific human capital (e.g. by entering a less physical occupation, or learning to use adaptations), which should reduce the extent of disadvantage experienced over time. Consistent with this, the impact of disability has been found to be greater among older onset groups across several countries, including the US, the UK, and Australia.

Limitations and gaps

Relative to research on other protected characteristics such as gender or race, evidence on disability is still scarce. This is partly because disability is more difficult to define and measure, and these issues are exacerbated in comparisons across time or countries. Indeed, even within a country, relatively small changes in the order and nature of survey questions used to identify disability can have important consequences for measuring disability and disability-related gaps. Even in the absence of changes in survey questions, changes in the institutional and policy environment can affect disability prevalence (and therefore disability-related gaps in the labor market) by changing the threshold at which functional limitations become disabling. In this respect, future research could usefully explore the dynamic relationship between (i) self-reported disability and more objective measures of health, and (ii) self-reported disability and receipt of disability benefits, possibly by linking survey data to administrative records. This may shed light on important issues such as for whom and at what point health conditions become disabling and lead to welfare support, and who is subsequently most likely to exit welfare support and/or disability. It is evidence of this nature that will help develop proactive policy measures which prevent disability onset and support exit from disability.

The disadvantage associated with disability is typically considered at the level of the individual, but useful insights may be afforded by considering the household, both in terms of patterns of onset and also in terms of the wider impact of disability. Important questions include the likelihood of disability passing from one generation to the next as well as the household clustering of disability prevalence. In a similar vein, studies need to consider the household implications of disability onset, such as the impact on spousal labor supply and/or workless households.

Future research should acknowledge that the influence of disability depends on both the nature of disability and the characteristics and circumstances of the individual. In this respect, there are gaps in knowledge in relation to key events such as (i) job retention, where there is a lack of evidence on the role of job, employer, and workplace adjustment in particular, and (ii) the school-to-work transition. Indeed, the percentage of disabled people in Europe aged 15–24 who are not in employment, education, or training (24%) is twice that of non-disabled individuals (12%), suggesting an important role for early policy intervention.

More detailed information on the nature of disability, including duration and severity, is often missing from national survey data that are typically used to analyze labor market outcomes. The simple binary measure (i.e. disabled or not), while having the advantage of simplicity, ignores substantial intra-group heterogeneity. Indeed, there is a clear need for evidence that distinguishes between conditions, particularly with respect to physical and mental health problems which are likely to have distinct labor market barriers, especially given that the latter is typically associated with more severe disadvantage [4] and has been linked to rising numbers of disability welfare claimants.

In the current context, perhaps the most important omission from the literature is a clear picture of what works in terms of policy. This is despite considerable political and policy attention on the disability employment gap in many developed countries. The lack of consensus in part reflects the fragmented nature of the evidence, which often focuses on individual schemes, including quotas, sheltered employment, wage subsidies, welfare reform, and employment support, which are features of particular institutional environments and where the results are not easily generalizable. Where there has been deeper international investigation, such as the evaluation of equality legislation, the absence of a positive effect simply demonstrates how complex and difficult the challenge is for policy.

Summary and policy advice

Descriptive evidence based on national surveys provides insights into the prevalence of disability and the scale of associated labor market disadvantages. It is important to recognize, however, that since disabled individuals are often disadvantaged relative to non-disabled individuals pre-onset (e.g. in terms of educational attainment), such comparisons may overstate the true influence of disability. Identifying the causal influence of disability is difficult, but the existing longitudinal evidence points to a negative onset effect, which, for those with severe and persistent disability, is exacerbated over time [12]. More positively, longitudinal analysis also identifies that disability onset is not necessarily permanent and that the disadvantage associated with temporary disability is frequently less severe and short-term.

Typically, less than half of the raw cross-sectional gaps in employment or earnings associated with disability are explained by other observable factors, such as education. The reasons for the residual disadvantage, however, remain contested, with the (unobserved) influence of disability on productivity and preferences for work proving difficult to separate from discrimination, resulting in discrimination potentially being overestimated. Nevertheless, there is little evidence that legislation prohibiting disability discrimination in countries such as the UK and the US has led to a narrowing of the disability employment gap.

Given the lack of consensus about what works in terms of policy, it is worth noting that disability is heterogeneous, and that differences in the type, severity, and chronicity of disability are fundamental to the pattern of disadvantage experienced. They are therefore likely to be critical to the design of effective support mechanisms. Indeed, recent studies highlight the importance of a more tailored policy response and, in particular, matching individual job demands to functional limitations in order to mitigate negative productivity effects in work. Consistent with this, there is increasing recognition of the importance of the employer and of effective occupational health in supporting flexibility and adjustments to work in order to enable employees to retain and/or re-engage with work. The government also plays an important role in this regard, such as by providing incentives for employers to retain disabled workers and by designing welfare systems that support disabled individuals in work. In contrast, many current welfare schemes provide support that is conditional on not working. The broadening of permitted employment and/or the provision of temporary financial support to facilitate work-related adjustments would appear to provide greater incentives for disabled individuals to remain in work, or return to work, when they are able.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author also thanks Peter Sloane for helpful comments on the original version. Version 2 of the article includes information on the use of anonymous job applications to detect hiring discrimination, reports on the increasing attention given to disability-related labor market disadvantage internationally, and updates the reference lists.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Melanie Jones

The definition and measurement of disability

Source: Bound, J. “Self-reported versus objective measures of health in retirement models.” Journal of Human Resources 26:1 (1991): 106−138.