Elevator pitch

Millions of people enter (or remain in) countries without permission as they flee violence, war, or economic hardship. Regularization policies that offer residence and work rights have multiple and multi-layered effects on the economy and society, but they always directly affect the labor market opportunities of those who are regularized. Large numbers of undocumented people in many countries, a new political willingness to fight for human and civil rights, and dramatically increasing refugee flows mean continued pressure to enact regularization policies.

Key findings

Pros

More job and occupational mobility allow regularized workers to search for jobs without fear of deportation.

Regularization leads to higher wages through better jobs and because wage exploitation is harder to hide.

Workers may become more productive after regularization because they can work in an occupation for which they are trained, more freely invest in human capital, or receive job training without fear of deportation.

Massive refugee flows indicate an ongoing demand for regularization; denied asylum claims may lead to large populations of undocumented residents.

Regularization can reduce labor exploitation among undocumented workers.

Cons

The impact of regularization on employment is unclear; some researchers find rising employment for men and falling employment for women and some find the reverse.

Regularization tied to employment contracts inhibits wage increases that would normally be associated with greater job and occupational mobility.

Little is known about regularization’s impact in European countries because of a lack of adequate data and studies.

Native workers often oppose regularization because they fear increased competition for jobs.

Author's main message

Regularization can improve the economic welfare of workers, especially if they can freely move through the labor market. A policy that does not require employment contracts with a specific employer or where an employer applies on behalf of the undocumented worker is more likely to increase job and occupational mobility, which leads to higher wages for regularized workers. As such, policymakers should consider a policy option with few employment restrictions. When employment conditions are required, the positive wage impacts of regularization are likely to be muted, as some pathways to the benefits are closed.

Motivation

People migrate across national borders for many reasons. Some leave their home countries in search of freedom or new job opportunities, some to escape poverty and a lack of jobs, and some are forcibly displaced—fleeing war, violence, and ethnic conflict. Whether from clandestine border crossing, visa overstaying, denied asylum applications, or for other reasons, migrants may live in a new country without the sanction of its government, thus becoming undocumented residents. Rapidly rising numbers of refugees from the Middle East and Central America have escalated migration flows, with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimating that there were more than 60 million forcibly displaced persons worldwide in mid-2015 [1].

Undocumented immigrants live and work in the shadows to avoid deportation. Without working papers or the equivalent, they often work in informal or underground jobs. Family, social, or organized migration networks typically help them find jobs where other undocumented residents work, leading to job sites where the undocumented make up the majority of workers. Sometimes, migration networks emerge as human trafficking organizations and workers experience exploitation. Employers may take advantage of undocumented workers’ lack of legal status by paying them less and making them work harder, since their ability to search for better jobs is impeded by their status. Undocumented residents, particularly women, are vulnerable to labor exploitation and sexual abuse because of their fear of deportation.

Legislators around the world frequently prefer deportation to regularization policies due to economic, social, or political reasons. Native workers frequently question the validity of regularizing workers, who may subsequently compete with them for jobs, and thus pressure legislators to resist regularization. Communities often question undocumented residents’ ability to adequately integrate into the local society, and may raise concerns about costs to local institutions such as school districts. Some argue that regularization will beget more migration because it changes incentives to migrate. If it increases migration, then new regularization policies may be needed—thus changing incentives to migrate in the future. This incentive spiral is seen as unfair to those who are waiting (and are eligible) to enter a country legally.

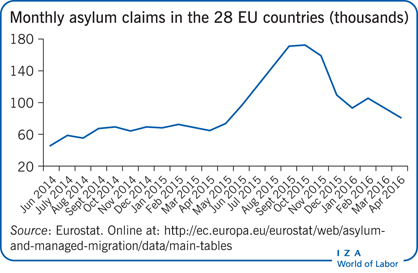

Nonetheless, countries still enact regularization policies that legitimate undocumented residents. The US, most of Europe, Malaysia, and other countries have enacted dozens of such policies over the last 40 years, regularizing millions of residents in the process. Importantly, the forces that create the need for regularization policies are growing stronger in many countries. Large numbers of undocumented residents, a new political willingness on the part of the undocumented to fight for future rights, and the current surge in refugee flows all suggest that there will be ongoing pressure for new regularization policies. The Illustration documents the recent extraordinary rise of asylum applications in European countries. Denied asylum applications often lead to undocumented residence and large numbers of undocumented residents create demand for new policies.

Discussion of pros and cons

Whatever the goals of regularization policies, they will always have both direct and indirect effects on the labor market. Informed policymakers must anticipate the ways in which these initiatives alter work opportunities for the newly legalized, other immigrant workers, native workers, and non-working residents of any status. Whether those changes are positive or negative depends on the characteristics of workers and non-workers in each group, institutional features of the labor market, a country’s labor policies, and the overarching economic context. They also depend critically on the kind of policy that is enacted. Some, like the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in the US, are wide sweeping, while others, like Spain’s 2005 regularization, are targeted specifically at workers. The following discussion focuses exclusively on the labor market consequences of regularization for regularized workers themselves, addressing the employment, wage, and human capital investment consequences specifically. Aside from these work-related aspects, policymakers will also have to consider potential indirect consequences (such as those on health care or school systems) of any proposed regularization policies, which are not discussed here.

Work and legal status

Undocumented workers face a difficult work environment. Multiple studies in the US, Italy, Spain, Germany, other countries in Europe, and elsewhere consistently find that working while undocumented is associated with constrained employment. The undocumented have access to fewer jobs and earn lower wages than other workers. Employers may use their workers’ lack of legal status to pay below minimum wages. In general, job matches are worse for the undocumented because both the worker and the employer fear being caught by the authorities. The constraints to employment differ from country to country and vary from not having access to the best jobs to working in highly abusive labor conditions.

Undocumented workers are typically unable to utilize human capital credentials such as licenses or school certificates and may not be able to work in the occupation for which they were trained. These credentials are more likely to be accepted in formal sector jobs, which are not usually available to the undocumented worker. Undocumented workers are unlikely to receive training or other human capital investments from their employers because hiring them is risky and their deportation would lead to the loss of the employer’s investment. These workers are unlikely to invest in their own education and training for the same reasons. Moreover, they typically do not have access to formal educational institutions; as such, this channel of human capital improvement is closed to them. Wages are lower for undocumented workers than they would be if they had the right to work.

Does becoming regularized change workers’ outcomes? This critical question is difficult to answer. The best answer requires a comparison of workers’ outcomes before and after legalization rather than a comparison of outcomes for undocumented and legal immigrant workers. Differences between these two groups are not particularly informative because systematic and sometimes unobservable differences besides documentation status exist between them. It also requires comparison with a control group that includes workers who are not regularized to establish that it is regularization (and not some other unknown change at the same time) that produces the results. Unfortunately, there are no data sets in the world that satisfy these requirements. Researchers attempt to use available data in creative ways to get partial answers: they link different data sets, utilize innovative techniques, and compare outcomes for regularized residents and comparison, rather than control, groups.

The jobs of the undocumented

Undocumented workers work in particular jobs, in sub-par occupations, and in certain industries, to avoid apprehension by the authorities. Workers may continue to work in jobs where an employer is abusive because they can avoid apprehension or because they fear the employer will turn them in if they quit. They often do not work in the occupation for which they were trained because they do not have appropriate credentials, or cannot use the credentials they have, in the new country. Job matching is based less on productivity than on secrecy, leading to poorer job matches. Employment in the informal sector, in underground and unregulated jobs, or in private households is often a worker’s best employment option. A lack of the right to work along with the need for secrecy means that undocumented workers congregate in certain jobs, leading to extreme occupational and industrial concentration. As a specific example, two in five formerly undocumented women in the US began their US working lives as household servants or childcare workers, and four in five worked in one of ten specific occupations (there are about 700 officially defined occupations in the US). Even while workers are undocumented there can be significant job mobility, but it is typically within this same small group of occupations [2]. Work in the construction industry, agriculture, private households, and in hidden areas of the service and food industry (such as restaurant kitchen help, hotel maids and janitors, or groundskeepers) is most common for the same reasons.

Simply looking for work in this environment can be dangerous and casual labor arrangements are common. In big US cities, potential workers congregate on street corners, in the parking lots of relevant businesses (like plant nurseries), or at highway off ramps. Employers drive by and, after a short negotiation, transport workers to an employment site. Tales of overwork, a lack of breaks, being underpaid or unpaid, or threatened with exposure are common. Being hidden from the authorities can be synonymous with being excluded from labor rights. Both men and women frequently work in agricultural jobs, living on-site in farm camps and being shuttled from farm to farm. Women can be particularly vulnerable because many work in private households where potential labor abuse is nearly invisible. Even without working papers people have labor rights in many countries, but they cannot be exercised without exposure to the authorities. While the specifics may differ, undocumented workers in many countries work in similarly abusive conditions.

The job consequences of regularization

Regularization allows workers to integrate more widely into the labor market. Once regularized, workers do not have to hide in the shadows and can look for new jobs without fear of exposure. Studies also reveal that occupational mobility was swift for regularized workers in the US (although the size of the effect varies considerably for different workers). Male Mexican workers, two-thirds of whom held one of ten traditional occupations as their first US job before regularization, illustrate how quickly occupational mobility took place after regularization. Fewer than two out of ten remained in one of those same ten occupations two years after regularization. Further, 70% reported changing occupations again after regularization, and with those changes there was significant occupational dispersion: only 40% were employed in one of the (new) ten occupations with the highest percentage of workers after regularization [3]. Better job matching means higher productivity for workers. Occupational mobility is significant because finding new and better jobs leads to increased wages after regularization.

However, it is not clear whether employment rises or falls with regularization, and its impact may differ by gender. Some research on the IRCA’s employment impact shows that employment fell for men because of unemployment but fell for women because they left the labor force and were no longer looking for jobs [4]. It is not known whether some women left the labor force because their spouses began to earn higher wages after regularization and there was less need for both spouses to work. However, other studies show increased employment for women as a result of regularization, possibly because regularization allows women to actively search for jobs [5]. Some related policies in the US (like the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act) appear to have had an insignificant effect on employment rates.

Regularization’s effect on employment obviously depends on the policy specifics. A number of programs in Europe require a job contract with a specific employer for a specific amount of time as a condition for regularization. Italy’s 2002 law (Legge Bossi-Fini) required employment before regularization, a one-year employment contract after regularization, and a certain length of residency. The prospect of regularization increased employment as undocumented workers who met the residency requirement scrambled to obtain steady employment in order to be fully qualified. Empirical work examining this “prospect” effect found that the employment probabilities for those who qualified on the basis of residency rose significantly but not for those who did not meet the residence requirements. As a result, there was a gap of more than 30 percentage points in the employment rate of the two groups one to two years after regularization [6].

Job or occupational mobility leading to higher wages is not always possible given the conditions of the regularization policy. Spain’s 2005 regularization program required proof of one year of employment with a specific employer or a contract for one year of future employment. As a result, neither job nor occupational mobility was likely in the immediate aftermath of regularization because workers were tied to specific jobs. Italy’s 2009 policy (Legge 94), which only allowed employers to submit applications on behalf of workers, effectively prevented workers from leaving an employer between the start of the application and final legalization, even though the process could take years.

Employment-based policies like those described above are often used as a signal for some desirable characteristics that indicate a resident deserves regularization. Employment may be seen as “a condition for integration, as a way to enhance selective migration policies, or as a guarantee of economic deservingness” [7]. Yet, some employment requirements hinder those very goals because they restrict workers’ mobility. Employment-based regularization policies are often attempts to regularize and formalize jobs as much as workers. Conditions in those jobs may improve, but job or occupational mobility is limited or unavailable in the short term.

The wages of the undocumented

It is almost universally found that undocumented workers earn lower wages than legal immigrants. Several issues arise when thinking about regularization’s impact on wages, and policymakers need to understand the differences among them. Undocumented workers may earn lower wages than legal immigrants because their human capital skills are less developed, their job experience and other productivity characteristics (like education, language skills, experience) are lower, and the local supply of unskilled workers may be higher—especially if, as in many countries, the undocumented tend to live and work in a few specific areas. There may also be differences in unobserved characteristics between undocumented and legal immigrants that drive wage differences.

In addition, it appears conclusive that undocumented workers earn lower wages than they would if they had the legal right to work (i.e. the same person working in the same job would earn higher wages if they were regularized, as opposed to undocumented). This fact is key to understanding the need for regularization policies and their potential impact on affected workers. The lower wages experienced by undocumented workers run the gamut from less pay for equal work, to outright wage abuse and the withholding of wages. Undocumented workers receive lower returns to their productivity characteristics—especially experience—because of sub-optimal job matches resulting from the need for secrecy, an inability to use home country credentials in the informal market, and because some employers practice outright wage fraud, discrimination, and abuse. Regularization can lead to an increase in wage earnings in all of these situations.

Evidence shows that workers experience a wage penalty while they are undocumented and receive higher wages after regularization—although they may never make up the wages lost during their undocumented time [8]. The size of the estimated wage increase varies substantially by policy and country, but nearly all studies investigating the impact of the IRCA found the wage effect of regularization to be positive: the magnitude ranged from 2−10% for men and from 0−21% for continuously employed women (though much less is known about the wage effects of regularization for women). Wages for IRCA-regularized workers increased more than those for comparable workers over the same time period [8]. Once workers were regularized, they earned higher returns to their productivity characteristics. Regularized workers were also able to earn higher returns to their existing skills; this holds true if they were in the same jobs they had before regularization or in new jobs. Since job and occupational mobility is a common consequence of regularization (among men), earning higher wages as a result makes theoretical and empirical sense.

The wage consequences of regularization

There are almost no studies about the wage impact of regularization in European countries, principally because adequate data for an investigation do not exist. One study shows that legal workers earn higher wages than undocumented workers in Spain, with a significant amount of the difference attributed to legal status even though it is not clear whether regularization would lead to higher wages for undocumented workers [9]. Another suggests, but cannot substantiate, that workers may have accepted drastic wage cuts to qualify for regularization under Italy’s employment-based policy [6]. Impacts in the US are better known and provide some hints as to the potential impacts in Europe. If the principal path to higher wages is job or occupational mobility, then specific regularization policies that require the employer to make the application on behalf of the worker, or that require continued employment with a specific employer, could lessen or prevent higher earnings. Wage increases resulting from employment-tied regularization may not arise in the short term, but only several years later, after employment contracts expire and workers are finally mobile. Findings on the 2002 Italian regularization policy in the years immediately after regularization are consistent with this problem [10]. However, these types of policies may still lead to higher wages for workers that remain in the same jobs, if those jobs transition from the informal to the formal sector.

Stringent data requirements make it difficult to predict the wage impact of regularization but many studies have uncovered heterogeneous results. For a policy to achieve its goals, policymakers should pay attention to the possibility of this heterogeneity. As an example, the existence and size of the increase in wages appears to be heterogeneous with respect to skills and gender. Highly-skilled workers are more likely to experience wage benefits from regularization than low-skilled workers, while women may not experience wage increases at all [2], [5]. Women were likely to work alone (as household help) and may have a more difficult time transitioning to a new job after regularization. Instead of higher wages, their benefits may be less tangible, including better and safer working conditions. While workers do not all receive the same economic benefits immediately, the social safety benefits, such as not being vulnerable to abuse and blackmail because of a lack of legal status, are always substantial.

Many countries, especially those in the Middle East and South East Asia, have large contract labor and temporary guest worker programs that lead to similar wage problems and human rights issues for temporary workers as those encountered by undocumented workers (i.e. low returns to their skills or experience or other wage abuses). Temporary guest worker programs often result in larger undocumented populations because wage abuse can be particularly endemic with contract labor—sometimes inducing workers to flee—or because employers may simply fire workers as contracts expire or if they no longer want to employ them. As a result, policies are needed to regulate such programs and to deal with any undocumented residents resulting from these programs’ problems. As an example of one such policy, Malaysia has passed a number of laws to alter contracting or sub-contracting labor arrangements (particularly for household labor): these laws set minimum wages and pay scales, require other improved conditions of employment, and include regularization policies to register undocumented workers [11].

The self-investment of the undocumented

Undocumented residents live in daily fear that they will be deported and returned to their home country. They know that being apprehended by the authorities almost certainly means they will lose their job. As a result, workers significantly discount the returns on any self-investment and have little incentive to take time off work for training, schooling, or language classes. Similarly, employers have little incentive to provide skills-enhancement training or education benefits because they could lose their investment in any worker who is apprehended. Enrolling in a training program may even increase the probability of encountering the authorities, further eroding the incentives to engage in human capital investment.

Little is known about the self-investment consequences of regularization because that requires specific information about changing skills over time. It is common for workers to have more measureable skills after regularization than before, but the reason for the skill increase is not known. It may simply be a consequence of more time in the host country rather than regularization. Language skills, for example, are likely to improve with time. But enrollment in language classes is also a known consequence of regularization. There is at least one study suggesting that regularization may have led to a four percentage point increase in men who speak English well. However, there is no known language improvement effect for women [5].

Limitations and gaps

There are obvious limitations to the existing knowledge on the impact of regularization in European countries due to a lack of empirical work on the subject. Additionally, much less is known about the consequences of regularization for women than for men. What is known implies gender specific effects of regularization such as those discussed above [2], [5]. Further, the existing research on women generates contradictory results; for instance, it is unclear whether women’s employment increases or decreases. While the benefits of regularization seem to be positively related to skills for men, they may be negatively related for women. Further investigation into the consequences of regularization for women is therefore critical.

There are significant methodological challenges facing any investigation into the consequences of regularization. Data that adequately document such effects are virtually non-existent. Conducting studies with sufficient randomization, information on labor outcomes before and after regularization, and a good control group all require huge resources and encounter privacy concerns. Researchers have made creative use of natural experiments, alternative data sets, and predicting legal status to estimate the effects of legal status, but identification issues often make estimates less than adequate. One data set satisfies part of this requirement: the IRCA mandated several reports on its impact and government agencies provided the resources that led to the creation of the Legalized Population Survey (LPS). LPS is an important source of evidence on the impact of regularization because it is one of the few data sets that contain information on residents both before and after their regularization. Policymakers should consider adding similar reporting requirements to any proposed regularization legislation to help evaluate its impact.

There are some studies on the employment impact of regularization policies in Europe, but the wage impact of the many European policies is simply not known. This gap in our knowledge, along with the different conditions and requirements to apply for regularization, makes it difficult to predict the impact of future regularization policies. It is certain that workers will not gain the wage benefits of job or occupational mobility if regularization is tied to an employment contract. A policy that does not require employment is more likely to lead to wage gains, but empirical studies of this are mostly drawn from a single policy: the US experience with the IRCA. Wages may not change in the same way as a result of policies in European countries.

Summary and policy advice

Policymakers who are considering future policies will need to be clear about their policy’s goals. Because regularization policies vary in their conditions and requirements, so too will the resulting outcomes. If the policy’s goal is simply legal residence then the requirements to apply may matter less than if there are also labor market goals for regularized or other workers. Workers will not gain the wage benefits of job or occupational mobility if a future employment contract is required for regularization, though an employment requirement that is solely present at the time of application may lead to significant employment increases among the undocumented population prior to application. A policy that does not require employment is more likely to lead to wage gains if workers can move freely through the labor market. Findings from the US that utilize the most comprehensive data available show that wage gains principally arise because of job and occupational mobility; as such, policies that are not tied to employment may bring about the most positive impacts for regularized populations.

Regularization policies can be beneficial for governments, people, communities, and economies, but the specific conditions of the policy drive actual outcomes. In particular, legislators must balance the needs and demands of all residents and workers, not just those who are regularized, when they consider the effects of potential policies. Overall, little is known about the empirical impact of these policies on communities and economies, though more is known about the effect of regularization on those who are regularized. Evidence suggests that regularization policies can have a significantly positive impact on undocumented workers, although the size—and the presence of an occasional negative impact—is context specific. Importantly, evidence suggests that the undocumented are most helped by regularization policies when there are few restrictions on post-regularization mobility and work behavior.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here [2], [3], [8].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Sherrie A. Kossoudji