Elevator pitch

Estimating the causal effect of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers has been a major concern in the literature. Because immigrants decide whether and where to migrate, immigrant populations generally consist of individuals with characteristics that differ from those of a randomly selected sample. One solution is to focus on events such as civil wars and natural catastrophes that generate rapid and unexpected flows of refugees into a country unrelated to their personal characteristics, location, and employment preferences. These “natural experiments” yield estimates that find small negative effects on native workers’ employment but not on wages.

Key findings

Pros

Refugee flows into a country are generally due to reasons unrelated to the immigrants’ location and employment preferences.

Refugee flows bring in a massive number of immigrants within a short period.

The location of refugees within the host country is generally determined by the host government based on security, logistic, and social concerns.

From the host country perspective, refugee flows are mostly unexpected events that can be considered immigration shocks.

Cons

Refugee inflows to a region can trigger an outflow of native workers from the refugee-receiving regions to other regions in the host country, creating new selectivity problems.

The skill composition of refugees may affect their impact on native workers’ labor market outcomes.

The impact of refugees may also depend on the existing stock of immigrants, which affects the absorption capacity of local labor markets.

In the longer term, the occupational distribution of the refugee population may be influenced by the relative returns across occupations in the host labor market.

Author's main message

Countries are concerned that immigration may cause the employment and wages of native workers to fall. To estimate such causal effects, the decision on whether and where to migrate has to be randomly assigned. A close substitute is to exploit natural experiments, such as sudden and rapid refugee flows. Estimates based on refugee flows find larger short-term impacts than long-term impacts, since local labor markets tend to adjust in the long term. Thus, policymakers should focus on targeted labor market policies and social programs that jointly facilitate the integration of refugee workers into local labor markets in the short term.

Motivation

The impact of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native-born workers has been a central issue of public debate. The main concern is that immigration can reduce the employment opportunities of native workers and generate downward pressure on their wages. A large body of literature has tried to test the validity of this conjecture. Although the most widely sought estimates are those that can demonstrate causality, they are rarely obtained. The problem is that immigrants select their place of residence, and they tend to move into areas with better labor market opportunities. This selectivity suggests that immigrant populations in a given region generally consist of individuals with certain characteristics, both observed and unobserved in the data, which will be quite different from the characteristics of a randomly selected sample of immigrants. Random selection—or something close to it—is however needed for demonstrating causality.

The literature offers several remedies based on standard econometric approaches. These remedies try to minimize the selectivity problem inherent in the standard data sets. An alternative is to set up an environment in which the choice of location is generated by a randomized experiment. One way to study immigrant flows similar to those that would be generated through a randomized experiment is to look at forced movements of refugees from one country to another in response to external forces (such as harsh political conditions, civil war, or natural catastrophes) that are unrelated to the individuals’ location preferences. This paper looks at the pros and cons of such a natural experiment approach.

Discussion of pros and cons

Whether countries should admit immigrants to benefit from a less expensive workforce or prevent their entry to avoid the potential negative impacts of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers has been a major policy tradeoff in traditional receiving countries, such as Australia, Canada, France, Germany, and the US. To elucidate this tradeoff, many empirical studies have tried to estimate the impact of immigration on native workers’ wage and employment outcomes. Several empirical approaches have been used in these studies, and they differ from each other in many ways, including their assumptions, data, context, empirical methods, and underlying theoretical construct.

In addition to refugee flows, country-specific policies for randomly distributing refugees across different regions within a country also offer valuable opportunities to estimate the causal effect of immigration on various outcomes. Examples of these policies include the Danish spatial dispersal policy, the policy of randomly assigning refugees to municipalities implemented in Sweden between 1985 and 1991, and the resettlement across Germany of ethnic Germans returning from Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union after 1989.

There are also immigrant lottery programs that randomly select immigrants from among a large set of applicants. The migration lottery program in New Zealand, the H1-B visa lottery in the US (a temporary foreign worker program), and the US Diversity Visa Lottery can be listed among popular immigration ballots. These cases are not examined here, however.

Main empirical approaches

The empirical literature can be grouped into three main categories. The first set of studies directly exploits the cross-sectional variations in the density of immigrants across cities or regions within a country to identify the effect of immigration on the outcome of interest. A common criticism of this approach is that immigrants may move (relatively) freely within a country, which suggests that the differences in labor market outcomes across cities or regions will be washed out through market forces. So, although immigration may have a large effect at the national level, the impact may not be visible within a cross-section of cities or regions in a country. This criticism implies that immigrants tend to move into the areas with better labor market opportunities. This selection problem (endogeneity), in turn, will likely lead to an underestimation of the true impact of immigration on native workers’ labor market outcomes. In other words, even if market forces do not operate perfectly, the selectivity problem will mask the true effect. Although several studies have applied standard methods for dealing with selectivity, doing so is always a challenge. Overall, these studies document that immigration has a quite small (and sometimes negligible) effect on the labor market outcomes of native workers.

A second set of studies adopts a production function approach, which relates production inputs to production outputs, based on estimating the degree of substitutability between immigrant and native workers. Immigration leads to a change in the relative abundance of immigrant workers. What effect this change will have on the wage and employment outcomes of native workers depends on the degree of substitutability between native and immigrant workers and labor demand conditions. This approach is criticized mainly because of the sensitivity of its estimates to the specification of the production function. These studies estimate much larger effects of immigrants on native workers’ labor market outcomes than do the first set of studies.

Finally, there is also a set of studies that rely on a specific type of immigration: refugee flows. These studies are regarded as natural experiments since the underlying reason for immigration is unrelated to the location preferences of immigrants. To be specific, the immigrant flows in these studies are generated through factors (such as political developments, civil war, or natural catastrophes) that are not related to the factors driving the location choices of individuals (they are exogenous). The studies adopting this approach document moderate negative effects of immigration on the employment outcomes of native workers. Some of these studies are examined below.

While the focus here is on the labor market impacts of refugee migration, the natural experiment approach in migration research can also be used to estimate the impact of immigration on many other outcomes, including consumer prices in the host region (and therefore the purchasing power of the native population), the prices of aid food, housing rents, educational outcomes, health and crime rates [8].

Benefits of the natural experiment approach

The natural experiment approach has several advantages over other approaches such as matching and instrumental variable (IV) approaches. Most important, the force that generates refugee inflows is mostly unrelated to the location preferences of the immigrants. The involuntary nature of refugee flows enables estimating the causal effect of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers without relying on the standard econometric methods for dealing with the selection problem, which have their own deficiencies.

Not only the decision to migrate, but also the choice of location within the host country is mostly beyond the control of the refugees in these studies. Sometimes, like in the case of ethnic Germans, refugees are allowed to state their preferences, e.g. to be allocated to regions where their relatives live. However, most of the time, the refugees are located by the host government based on considerations that are independent of the refugees’ location decisions. In some cases, governments aim to evenly distribute the refugees across the country to prevent any effects of too dense a concentration of refugees in one place. In some other cases, governments want to keep the refugees clustered in a specific region to increase the effectiveness of humanitarian aid. The region is often preferably chosen to be near the host country’s border with the refugees’ home country to facilitate their return when the underlying conflict or problem is resolved.

Another advantage of the natural experiment approach is that a massive inflow of refugees from one country to another happens unexpectedly within a very short period. This is like an exogenous labor supply shock. The size, timing, and duration of the shock do not allow labor demand conditions to adjust, at least not in the short term.

These factors constitute a setup in which immigration occurs as if it were generated through a randomized controlled trial. In the absence of real experiments, which are not easy to design in migration research, such natural experiments provide valuable opportunities to estimate the impact of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers without relying on overly strong identifying assumptions and complex econometric procedures.

Potential disadvantages of the natural experiment approach

Despite the advantages, the natural experiment approach is not free of problems. Caution is still required in interpreting the estimates associated with natural experiments. To begin with, the biggest disadvantage of immigration generated through massive refugee inflows is that it may generate movements of native populations out of the refugee-receiving regions to other regions in the host country. In such a case, native workers with certain types of preferences and skills may leave the refugee-receiving region inducing selection among the native population.

For example, a massive influx of low-skill immigrants initially generates an over-supply of low-skill labor in the receiving region. Firms that typically employ low-skill workers will likely relocate to that region. As a result, the joint distribution of skills and jobs will change, and some native workers in the receiving region may be willing to incur the cost of leaving the region to search for better jobs. This means that the labor markets in the non-receiving regions will also be affected by the refugee influx, if indirectly. The resulting estimates will be biased, since the average characteristics of the native workers who choose to stay in the host region will be determined by the changed conditions there. This response suggests that the analysis has to ensure that the patterns of internal relocations of native workers do not exhibit significant changes following the inflow of refugees, or the analysis has to effectively control for this relocation of native workers.

The nature of the refugee problem directly determines the skill composition of the refugees. For example, in some cases, the average education and wealth of the refugees may be high (even higher than the average education and wealth of native workers residing in the region), while the opposite may be true in other cases. The skill composition of the refugee population can directly affect the impact of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers. The generalizability of findings would thus be limited in the case of extremely skewed distributions of refugee skills relative to the skill distribution of native workers.

Another concern is the size of the existing stock of immigrants in the host regions. This is of particular importance as the integration of refugees into the host labor markets will be much easier if there is a pre-existing immigrant network with a high degree of labor market integration. When there is no such network, the impact of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers may be much weaker.

Finally, the short- versus long-term consequences of immigration are another source of confusion in interpreting findings [9]. Refugee flows can be regarded as a good natural experiment in the short term. Over time, however, the occupational distribution of immigrants may respond to the relative returns to occupations in the host economy. On a related issue, the existing human capital stock of the refugees may not be fully valued in the host labor markets in the short term, while the “portability” of human capital will increase in the long term and the relative returns to skills may also change. These secondary effects operate mainly in the long term, which suggests that the short- versus long-term consequences of the refugee-based immigration on the labor market outcomes of natives should be clearly and carefully distinguished.

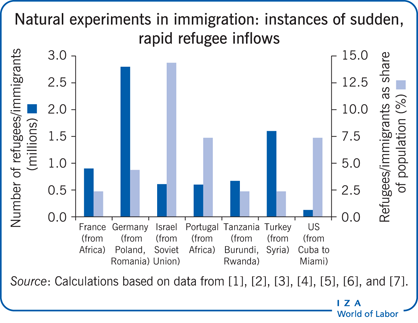

Some global examples of natural experiments

Cuba–US

One of the first examples of the natural experiment approach in migration research is the examination of the effects of the 1980 Mariel boatlift from Cuba on the Miami labor market in the US [7]. On April 20, 1980, Fidel Castro declared that Cubans who wanted to emigrate to the US were free to leave Cuba from the port of Mariel. Following that unexpected declaration, around 125,000 unskilled immigrants arrived in Miami over a period of about four months. Around half the immigrants settled in Miami, rapidly boosting the labor force in the city by some 7% and increasing the number of Cuban workers by 20%. This labor supply shock had virtually no impact on the labor market outcomes of native workers, largely, it is argued, because of the large number of Cubans already in the labor force in Miami, which facilitated the absorption of the newcomers [7].

Algeria–France

After Algeria declared independence from France in 1962, around 900,000 French expatriates returned to France within a short period of time—over about a year [1]. The inflow of expatriates represented about 1.6% of the French labor force of the time and constituted a large labor supply shock since the timing of immigration was totally independent of the economic conditions in France. The immigrants were mostly skilled, unlike the Cubans who arrived during the Mariel boatlift. One disadvantage of this setting is that the location choices of the immigrants within France were mostly driven by their own preferences, and most of them chose to live in southern France. A study found only small negative effects of repatriation on the labor market outcomes of native workers in the destination regions [1].

Angola and Mozambique–Portugal

Another example is the Portuguese repatriation (retornados) in the 1970s from Angola and Mozambique following independence of those former Portuguese colonies [4]. The return of the expatriates generated a labor supply shock as 600,000 workers (approximately 10% of the Portuguese workforce at the time) entered the labor market over just three years. The political event that generated the refugee flows was again independent of the economic conditions in the destination economy. Moreover, as in the French case, the skill levels of the Portuguese returnees were also high. The immigration had larger estimated negative effects on native workers’ labor market outcomes than those documented in other studies [4]. However, the mid-1970s was a period of poor economic performance across Europe, so it is difficult to clearly isolate the impact of immigration from the impact of aggregate economic conditions.

Former Soviet Union–Israel

One of the most well-known refugee flows is the influx of some 600,000 immigrants from the former Soviet Union to Israel from 1989 to 1994, which raised the population of Israel by around 12% [3]. The reason for the massive migration wave was the lifting of emigration restrictions in 1989. The majority of Jewish emigrants migrated to Israel, in part because it imposed no entry restrictions. As in the case of the French and Portuguese expatriates, the skill level of the Russian immigrants was high—at least as high as the average skill level of native Israeli workers in the 1990s. After correcting for post-immigration occupational choice among immigrants, the study found that immigration had virtually no adverse effects on the labor market outcomes of native Israeli workers [3].

Eastern Europe and former Soviet Union–Germany

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 offered another opportunity for a natural experiment on the impact of immigrants on the labor market outcomes of native workers [2]. After 1989, ethnic Germans living in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union were allowed to return to Germany; approximately three million ethnic Germans returned within 15 years. One distinguishing feature of this immigration experience is that the immigrants were settled across Germany to ensure an even distribution across the country. Since the immigrant inflows were triggered by an event unrelated to the economic conditions in Germany, they constituted a real labor supply shock. The supply shock had negative employment effects on native German workers, but the wage effects were negligible [2]. Although the return of ethnic Germans to Germany cannot be classified as a refugee flow, the nature of the sudden flow allows the study of its impacts to be categorized as a natural experiment.

Burundi and Rwanda–Tanzania

An example from Africa that has been extensively explored is the flow of refugees from Burundi and Rwanda to Northern Tanzania (Kagera) following the civil war and genocide in those countries [5]. In 1993, around 370,000 Burundians moved to Tanzania to escape the political turmoil that followed the assassination of Burundian president Melchior Ndadaye. The next year, as civil war spread throughout Rwanda, around 300,000 Rwandans fled to Tanzania. These two events almost doubled the population in Kagera within about 15 months in the mid-1990s. The distinguishing feature of this immigrant inflow is that it involved poor countries in which food shortages were already common at the time [10]. The refugee inflows had a slightly negative impact on the employment outcomes of Tanzanian agricultural workers [5].

Syria–Turkey

The most recent example is the ongoing inflow of refugees from northern Syria to south-eastern Turkey, which started in 2011 [6]. The Syrian civil war has displaced millions of people. The UN estimates that, by the end of 2014, around 3.6 million Syrian refugees had fled to neighboring countries, and that Turkey alone had received more than 1.6 million. The migration decisions of Syrian refugees to Turkey are independent of their location preferences. The refugee camps they live in are constructed and operated by the Turkish government. The demographic and educational composition of the refugees is comparable to that of the native workers living in the host regions, suggesting that the potential for substitutability in the workforce is high. Since both the decision to migrate and the location choice of the refugees are not controlled by the refugees, the natural experiment conditions were exploited to estimate the impact of Syrian refugees on the labor market outcomes of native workers. The study reports negative employment effects on native Turkish workers but no wage effects [6]. A distinguishing feature of this immigration flow is that the Syrian refugees are not allowed to work officially (as of the end of 2014), so the immediate employment effects operate mainly through the informal labor market.

Central America–US

Beside political events and civil conflicts, natural catastrophes can also generate immigration waves that are independent of the immigrants’ preferences [11]. In October 1998, Hurricane Mitch hit Central American countries including El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, and generated a large wave of immigration to southern ports in the US. Around 200,000 unskilled workers from these countries were granted temporary residency status in the US and were located in southern regions. Similar to the other cases mentioned here, the immigrant flows had some negative employment effects on native workers, but the wage effects were negligible [11].

Overall, these studies exploiting natural experiments to estimate the impact of immigration on the wage and employment outcomes of native workers consistently document two common findings.

First, immigration shocks have moderate negative effects on the employment outcomes of native workers: unemployment rates rise slightly among native workers as a result of the increased immigrant population in the host regions. Whether skilled or unskilled natives are affected more depends on the skill and occupational composition of refugee and host populations.

Second, wage outcomes of native workers are mostly unaffected.

Short-term versus long-term impacts of migration flows

Refugee inflows may have different short- and long-term impacts on the labor market outcomes of native workers. The literature based on natural experiments clearly documents that large inflows of immigrant workers will be absorbed by local labor markets, given time, and that the long-term equilibrium effects are usually smaller than the short-term effects. The findings of the studies based on natural experiments involving refugee inflows confirm this view. These studies suggest that the negative impact of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers is more clearly observed in the short term than in the long term, as local labor markets are more likely to adjust in the long term. Those studies also suggest that differences between short- and long-term impacts are greater for employment outcomes than for wage outcomes. Traditional studies of the impacts of immigration, which are not based on experimental methods, focus on the degree of complementarity between native workers and immigrants within a framework that relates production inputs to production outputs, comparing the skill composition of native workers relative to that of immigrants. These studies generally find little impact of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers in the short term and large positive impacts on employment and wages in the long term. In this sense, the results of traditional studies differ from those of studies based on natural experiments.

Limitations and gaps

The natural experiment approach to migration research is not free of problems; and these problems could pose challenges to estimating and interpreting causal effects. One major limitation is that the events that can generate an immigration shock independent of the location preferences of immigrants are extremely rare. Although political conflicts, civil unrest, and natural catastrophes are not infrequent, they rarely generate huge waves of population movements that can lead to a massive and unexpected inflow of immigrants within a short period.

Clearly, natural experiments have a great potential to ease the selectivity problem associated with the decision to migrate since location preference is irrelevant for a refugee who is forced to move from one country to another. However, further layers of selectivity can emerge following the forced movement.

First, whether the refugee can choose a location within the host country is crucial, since it can generate selective bunching of refugees in certain regions and thus bias the estimates.

Second, the refugee inflows can generate a large movement of native workers from refugee-receiving regions to other regions within the host country, which means that selectivity can operate among the native population.

Finally, the occupational distribution among the refugees in the post-immigration period may be affected by the relative returns to occupations in the host economy, which can also bias the estimates.

Finding the correct reference group is another key issue. Most of the studies based on refugee flows perform a type of analysis that depends critically on the choice of a relevant comparison region. Specifically, a reference (or control) region is needed in which the labor market outcomes would move very close to those in the refugee-receiving (or treatment) region absent immigration. It is not always possible to find the correct comparison group. A famous critique [12] of the estimate of the effect on labor market outcomes of native workers following the Mariel boatlift [7] shows why the choice of the correct comparison group is crucial.

Finally, the interpretability of the estimates obtained from the refugee data is limited by the extent to which refugee flows are an accurate proxy for normal migration flows. The legal status, admission rules, and work-permit conditions of refugees differ from those of migrants. Whether this distinction requires treating refugees and migrants differently in empirical analysis is a controversial issue and should be kept in mind when interpreting the estimates.

Summary and policy advice

Estimating the effect of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers has been a challenging task because immigrants choose whether and where to migrate; they are not assigned to countries on a random basis. Several econometric techniques are generally used in the literature to overcome this problem. The natural experiment approach offers an alternative path for estimating the impact of immigration on the labor market outcomes of native workers. This approach relies on episodes in which migrant flows are generated by factors that are mostly unrelated to the migration decision and location preferences of migrants—such as unexpected refugee flows due to political factors, civil conflict, and natural catastrophes.

Studies using this approach uniformly find that immigration somewhat reduces the employment prospects of native workers while having only a negligible impact on their wage outcomes. Although these studies shed light on the extent and nature of estimation biases arising from the location preferences of immigrants, the results need to be interpreted carefully as the particular nature of the refugee inflows may pose additional problems.

Finally, the short- and long-term impacts of refugee inflows may differ, with each having different implications for policy. The long-term impacts are generally much smaller than the short-term impacts, since local labor markets tend to adjust in the long term and absorb immigrant workers. This suggests that targeted labor market policies and social programs that jointly facilitate the integration of refugee workers into local labor markets may prove to be more effective in the short term than in the long term.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles. The analysis and conclusions expressed in this paper are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey.

© Semih Tumen