Elevator pitch

Non-experimental evaluations of programs compare individuals who choose to participate in a program to individuals who do not. Such comparisons run the risk of conflating non-random selection into the program with its causal effects. By randomly assigning individuals to participate in the program or not, experimental evaluations remove the potential for non-random selection to bias comparisons of participants and non-participants. In so doing, they provide compelling causal evidence of program effects. At the same time, experiments are not a panacea, and require careful design and interpretation.

Key findings

Pros

Experiments solve the problem of non-random selection and thus often provide compelling causal evidence of program effectiveness.

Policymakers and other stakeholders find experimental methods easier to understand than many non-experimental evaluation methods.

Experiments are, in general, more difficult for researchers to manipulate than non-experimental evaluations.

Experimental data provide a benchmark for the study of non-experimental approaches.

Cons

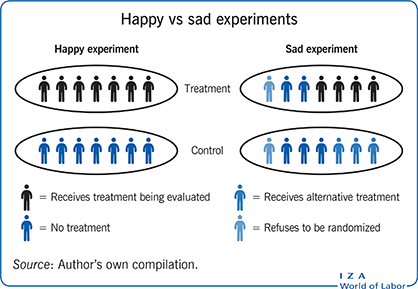

In many experiments, interpretation is complicated by the fact that some of those assigned to the program do not participate in it, and, equally, that some of those assigned to not receive it may actually do so (or else receive a similar program).

Many experimental evaluations allow individuals to opt out of random assignment, which reduces the findings’ generalizability.

To fill the control group, experiments may require changes in program scale or that programs serve people they would not otherwise.

Local programs that resist participation in an experimental evaluation may not be representative, thus limiting generalizability.