Elevator pitch

Companies frequently hire new employees based on referrals from existing employees, who often recommend friends or family members. There are numerous possible benefits from this, such as lower turnover, possibly higher productivity, lower recruiting costs, and beneficial commonalities related to shared employee values. On the other hand, hiring through employee referrals may disadvantage under-represented minorities, entail greater firm costs in the form of higher wages, lead to undesirable commonalities, and reflect nepotism. A growing body of research explores these considerations.

Key findings

Pros

Employees that are hired via referrals have lower turnover relative to non-referred employees.

Referred employees may have higher productivity than non-referred employees.

Firms may incur lower recruiting costs when hiring employees via referrals.

“Good homophily”: When firms hire referred employees, their workforce becomes more likeminded; this can be a positive if workers share values or characteristics that are desirable.

Cons

It is possible that hiring based on employee referrals could disadvantage women or minorities.

Referred employees sometimes receive higher wages relative to non-referred employees, which entails increased costs to the firm.

“Bad homophily”: Firms get employees like their existing employees; for example, firms might get less demographic diversity and/or employees with less diversity in opinions and ideas.

Referral hiring may reflect nepotism; friends and family may be hired instead of the best available candidates.

Author's main message

Evidence increasingly supports the idea that firms can benefit from hiring through employee referrals. At the same time, this hiring method can entail various costs that firms must consider. While data constraints have typically limited research on hiring through employee referrals, significant research progress is being made. Additional future research using natural experiments and/or randomized experiments may be particularly fruitful.

Motivation

It is well known that social networks play a key role in labor markets. Many positions are filled via employee referrals, where existing employees at a firm refer potential candidates for a job. Further, many firms provide referral bonuses to their employees to make referrals.

For firms, an important question with respect to hiring through employee referrals is to what extent referrals help or hinder the firm from accomplishing its business objectives. Hiring is an extremely important topic, but leading economists argue that it is substantially under-researched, particularly relative to other topics such as the study of incentives. A significant challenge involved in studying hiring practices and outcomes is the limited availability of data on the matching process between workers and firms. Given this dearth of information, it is worthwhile to review what economists actually know about the benefits and costs that firms receive from hiring through employee referrals. The focus of this article is on firms in developed countries, though there is also a growing body of work on the importance of referrals in developing countries.

The study of employee referrals and worker social networks has a rich tradition in economics. It also has a very strong tradition in sociology. As such, it is a topic where economists and sociologists may be able to work together fruitfully to make progress on difficult and unresolved issues, such as why there are differences between referrals and non-referrals, why people make referrals, and how much referrals matter for inequality.

Discussion of pros and cons

Turnover

One important pattern for referred employees is that they tend to have lower turnover rates than non-referred employees. This pattern has been documented in various labor market settings, including the US [2], Germany [3], and online labor markets [4]. In the US, lower turnover has been found in representative labor market studies [2], as well as in the context of certain jobs, including call-center workers, truckers, workers in financial services, and high-tech workers [5], [6].

One interesting finding is that differences between referred and non-referred employees in turnover may be larger at the beginning of a new employee’s tenure [3]. This gap may fade as tenure increases. Thus, after two employees (one referred and one non-referred) have been at a company long enough, the relative benefit in terms of turnover risk may start to diminish, though the literature does not clarify what qualifies as “long enough”. One possible explanation for this is that referrals are initially better-matched with firms than non-referrals. As information about fit between employees and firms is gradually revealed, the difference in fit between referrals and non-referrals diminishes over time, meaning that differences in turnover risk also diminish over time.

Conversely, other studies do not find that the turnover gap shrinks with tenure [6]. Differences in findings could reflect differences in the environment being studied; for example, one paper analyzes data from a large European metropolitan market [3], whereas the other studies data from a large US financial institution [6]. The findings in the European study may reflect trends in the labor market at large, whereas there may be variability within particular firms [6].

Productivity

Besides turnover, another very important variable for firms is worker productivity. It is thus relevant to examine if and to what extent employee referrals lead to more productive workers. Unfortunately, relatively little information exists about referrals and productivity because worker-level productivity data sets are not readily available. As summarized in [4], study findings have run the gamut, from referred employees having higher productivity, to referred employees having lower productivity, to referrals and non-referrals having similar productivity on most metrics.

However, the same study argues that selection during the hiring process can play an important role in whether referred employees are more productive than non-referred ones [4]. Firms try to hire the best candidates during the selection process, and differences in the selection process between referrals and non-referrals may affect whether there are productivity differences between referrals and non-referrals. Using an online labor market, the study obtained a large number of referred and non-referred applicants. However, rather than trying to hire the best applicants, the firm hired all applicants. This served to eliminate the selection pressure that typically occurs when firms attempt to hire the best available candidates, which frequently ends up with firms favoring referred candidates. The study can therefore shed light on whether referred applicants tend to be more productive than non-referred applicants. The authors find that referrals tend to be more productive than non-referrals, but that selection during the hiring process may be important for understanding productivity comparisons in general. For managers, this raises the possibility that the way that referrals and non-referrals are selected during the hiring process affects the nature of productivity differences after hiring.

Less recruiting cost

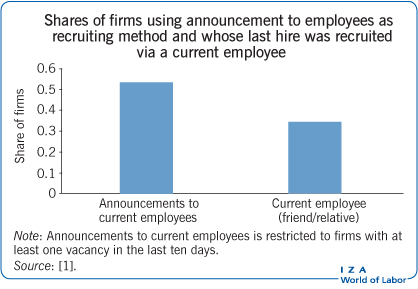

Another way in which referrals could be valuable for firms is if they lower the costs that firms incur when hiring new workers. For instance, firms need to spend less time conducting interviews and reading resumes when relying on referrals. Various studies in sociology and economics therefore argue that referrals help reduce recruiting costs [5], [1], [7]. That is, to achieve a hiring outcome through an employee referral, the cost of recruitment may be lower than to achieve a hiring outcome for a non-referred individual.

Good homophily

“Homophily” is a term often used by sociologists. It refers to people’s tendency to associate with people like themselves. Homophily is observed across a wide range of social phenomena. For example, people tend to be friends with people of similar ethnicities to themselves.

One way that employee referrals can be beneficial for firms is if they help leverage homophily with respect to desirable characteristics, such as productivity, attrition risk, or overall fit for the firm. For example, one recent study found that truck drivers tended to refer people with similar productivity (either in terms of miles or accidents) [5]. Thus, provided that individuals with higher productivity are more likely to make referrals (which could result for different reasons such as high productivity workers being more committed to an organization), firms can potentially benefit from those employees’ likeminded (i.e. similarly productive) referees.

One study on referrals in online labor markets also found that homophily on productivity is a common feature of referral relationships [4]. That is, more productive employees tend to refer people who are also more productive.

Potentially disadvantaging women and minorities

Despite its positive aspects, referral hiring could present a challenge for firms’ workplace diversity, especially given the tendency for employees to refer candidates with similar demographics as themselves [6]. One recent study argues that referrals could decrease diversity in the workplace [8]. The authors used data from a field experiment in Malawi and found that women seemed to be disadvantaged by the referral process relative to men. Specifically, they found that men were unlikely to refer women, and that women referred applicants who tended to perform worse (in terms of qualifying for a job) than applicants referred by men. This is an important finding, and it would certainly be worthwhile to examine similar issues in developed country economies as well (as cultural norms related to gender may be different between developed and developing countries).

Turning to ethnicity and back to the developed world, another study provides evidence from the US that black youth may receive less of a benefit from using informal methods to acquire jobs than white youth [9]. This occurs even though whites and blacks do not significantly differ in their likelihood of using friends or relatives in the job-finding process. In contrast, a study from the mid-1990s did not find lower returns to referrals for blacks (focusing on wages instead of job-finding), but did find lower returns to referrals for Hispanics.

In a rich and detailed ethnography, a book published in the late 1990s shows that disadvantaged blacks and Hispanics in New York frequently use social networks to find jobs. However, these social networks may lead to lower-skilled work, such as fast-food jobs. Individuals may be disadvantaged relative to others if they have fewer individuals with higher-skill or higher-paying jobs in their networks. This suggests an important point for policymakers that it is not only the size/quantity of an individual’s network that affects what types of job that person learns about, but also the “quality” of a person’s network. Increasing referral-based hiring could potentially disadvantage certain groups of people if there are differences across groups in the nature of their job networks.

The interaction between job networks and characteristics such as ethnicity and gender is complex. In the sociology literature, an influential paper from the mid-2000s argues that reputational considerations play a large role in the referral process. Specifically, minorities may be hesitant to make referrals if they are concerned that they will suffer reputational consequences from a referral that works out poorly. If an employee believes that their own position in the workplace is tenuous or that they have few outside options to pursue if things go sour, then that employee may be reluctant to make a referral.

Higher wages

One limitation of hiring through referrals (from the firm’s perspective) is that firms may need to pay referred employees more compared to non-referred employees (e.g. if referrals have higher productivity or match quality, or if referrals have an inside edge in negotiating higher salaries). The evidence is mixed, however, as different studies have reached different conclusions about whether referred employees earn more than non-referred employees [2].

One recent study examined differences over time between referred and non-referred employees in terms of wages at a large financial institution [6]. It found that referred employees started off earning more than non-referred employees. Over time, however, that difference faded away. A similar set of findings was recovered using data from Germany [3]. This pattern may reflect employers obtaining more precise initial information about worker quality for referred employees compared to non-referred employees. It should be noted that initial wages for referrals and non-referrals are the result of a complex hiring process. Moreover, paying higher wages is not necessarily a disadvantage for the firm if the higher wages reflect an employer having lower uncertainty about worker quality, as is the case of referred workers.

Bad homophily

Beyond possibly limiting diversity in terms of ethnicity, gender, and other background characteristics, referrals could also serve to perpetuate homophily along other dimensions. One of the main ones to consider is diversity of ideas and opinions. It should be recognized that diversity in terms of background characteristics may be linked to diversity of ideas or may improve other aspects of decision making. For example, one recent study in psychology argues that ethnic diversity increases market efficiency using an experimental asset market. Specifically, they find that market prices are closer to true values when market participants are more diverse.

Homophily may also be undesirable if referrals reflect nepotism. Placing too much value on family and family connections in the hiring (or promotion) process could cause people to lose faith in the idea that their organization is a meritocracy. Examples of nepotism in the hiring process can be found in numerous settings. Using data from Sweden, one study provides evidence that parents often help their children find jobs at the firm where they work [10]. A study using Chinese data shows that men whose fathers-in-law die experience significant drops in earnings, which is consistent with nepotism [11]. The idea is that men receive labor market assistance from their fathers-in-law (including getting help with being considered for higher paying jobs, perhaps in a nepotistic manner) and that such assistance ends upon a death.

It is not always easy to determine whether a source of homophily is “good” or “bad.” Organizations often have distinct cultures for various reasons (such as the founders’ influence, the type of product they provide, or the style and preferences of top managers). Some employees may be an excellent fit in one organization, but may struggle in a different one. Some organizations thrive on a brash, argumentative style, whereas others value polite and measured discourse. While referral hiring may attract individuals who are more like current employees, whether this is bad or good for an organization depends on the individual circumstances at play.

Limitations and gaps

Economics research on the value of hiring through employee referrals is still in its early stages, both in developed countries (the focus of this article) and globally. As such, a number of important limitations and gaps exist.

One very important question is: Why are there differences between referred and non-referred employees? Do referrals select better (or worse) individuals? Or rather, is there some feature of the workplace where referred employees behave differently for some reason? A recent study on online labor markets uses its experimental design to provide strong evidence for selection [4]. However, there is still much more research to be done on this important issue.

Another important question is why people make referrals to start with. If an organization wants to increase the quantity or quality of its referrals, it needs to understand why people make referrals. One study using a field experiment in India has made some exciting progress on this question [12]. The authors analyze how the size and structure of referral bonuses affect the quality of referrals (as well as the quantity of referrals). A separate ongoing study is conducting field experiments that provide evidence on why employees make referrals [13].

More research is also needed to measure the extent to which referrals may contribute to inequality. A central concern about referral-based hiring is that some people may be disadvantaged relative to others due to having more social connections than others. However, this issue may be viewed as conceptually separate from an examination of the main gains that firms experience from hiring through referrals.

Finally, more research is needed on the importance of sources of referrals (i.e. friends vs family vs others). Early research showed that job seekers are more likely to receive referrals from acquaintances instead of friends (i.e. weak ties instead of strong ties), though recent work using data from Facebook provides evidence that job finding success is more greatly enhanced by stronger personal ties instead of weaker ones. Economists may wish to study how the source of referrals relates to the value that firms receive.

Summary and policy advice

A growing body of research suggests that firms may experience significant benefits from hiring through employee referrals. However, the benefits are certainly not without costs (e.g. in terms of less diversity, higher wages, or bad homophily); as such, this article does not intend to suggest that firms should only focus on hiring referred candidates. Rather, firms should carefully examine how referrals are (or are not) adding value to their organization. In addition, firms should examine whether more can be done to improve the quality of referrals. Given the tendency for homophily in the referral process, one potential course of action is that firms could encourage referrals from their highest ability employees. Having said that, the evidence indicates that referring employees often have higher ability to start with; thus, it is possible that this advantage is already built into the referral process.

Firms that encourage referrals should make sure that their referral program is equitable, and is not just perpetuating the “old boys’ club.” Diversity is important for firms for many reasons (e.g. various studies suggests that diverse teams may perform better). To avoid a referral program leading to less diversity, a firm might encourage referrals of women and under-represented minorities to ensure that strong women and minority candidates are not left out of the referral process. As an example, the professional services firm Accenture announced in early 2016 that it would use “enhanced” referral bonuses for successful referrals of blacks, Hispanics, women, and veterans.

Finally, researchers and practitioners should continue to explore the value of hiring through referrals. As highlighted herein, there remain many important open questions. While this article has focused primarily on developed economies, the value of hiring through referrals in developing countries is also a very important issue.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Some of the broad arguments and ideas in this article draw on past work where additional references can be found [5]. Financial support from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Mitchell Hoffman