Elevator pitch

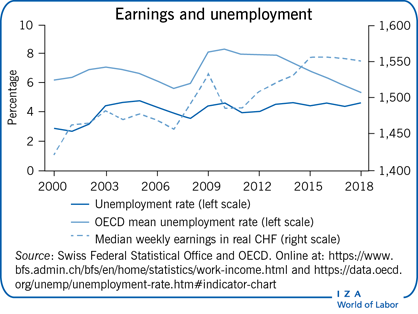

Switzerland is a small country with rich cultural and geographic diversity. The Swiss unemployment rate is low, at around 4%. The rate has remained at that level since the year 2000, despite a massive increase in the foreign labor force, the Great Recession, and a currency appreciation shock, demonstrating the Swiss labor market's impressive resiliency. However, challenges do exist, particularly related to earnings and employment gaps between foreign and native workers, as well as a narrowing but persistent gender pay gap. Additionally, regional differences in unemployment are significant.

Key findings

Pros

Unemployment has remained stable at a low level.

Wage inequality has remained low by international standards.

The labor market was only weakly affected by the recessions in 2001 and 2008 and recovered quickly.

There is no evidence that major events of the past 15 years—the eurozone crisis, the massive inflow of refugees, or the appreciation of the Swiss franc—negatively affected the labor market.

Cons

Unemployment among foreigners is more than twice as high as among Swiss citizens.

The wage gap between Swiss citizens and foreigners remains high, especially among men.

The long-term unemployment rate has increased and remains higher than the OECD average.

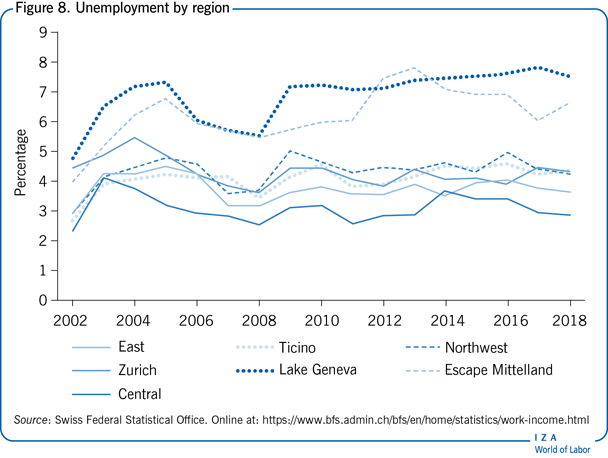

There are substantial regional differences in labor force participation and unemployment.

Author's main message

Overall, Switzerland's labor market is doing well. Unemployment has remained below 5%, and real earnings have been growing at a rate of about 0.5% per year since 2000. This success comes despite a massive expansion of the labor force of about 23% since 2000, the Great Recession, and appreciation of the local currency. Switzerland should maintain the policies that have supported this resilience and should resist new policy proposals that may endanger it. Beyond this, policymakers should strive to reverse an upward trend in long-term unemployment via job search incentivizing, and must find ways to address labor market differences between foreign and native workers, regions, and genders.

Motivation

After decades under relatively stable conditions, the Swiss labor market has faced major challenges since the turn of the millennium. The establishment of the free movement of people with the EU in 2002 led to a massive expansion of the labor force. In addition, the Swiss economy was burdened by the Great Recession and the unprecedented appreciation of the Swiss franc during the eurozone crisis. Despite these circumstances, low unemployment and steady wage growth have persisted over the past 20 years. However, other issues such as the regional differences in labor market performance, and across gender, continue to arouse concern.

Discussion of pros and cons

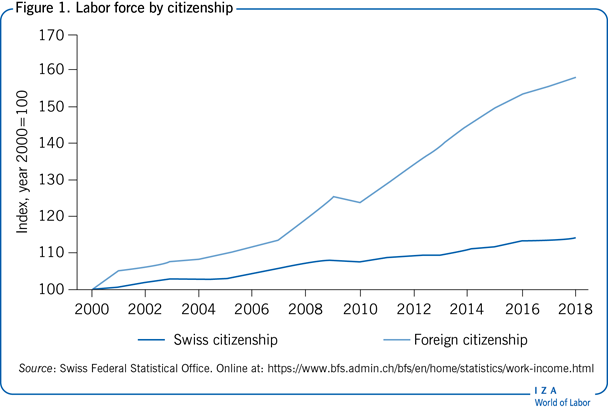

Since the turn of the millennium, Switzerland has deepened its integration into the EU's single market through the introduction of free movement of persons between Switzerland and the EU. Gradually implemented since 2002, this free movement of people allows EU citizens non-discriminatory access to the Swiss labor market. This facilitation of immigration is the most important cause for the impressive growth in the foreign labor force shown in Figure 1. At the same time, the Swiss labor force has grown at a slower pace; 90% of the growth of the Swiss labor force having been due to naturalization of foreigners. Overall, the labor force in Switzerland increased by 23% from 2000 to 2019. Today, foreigners account for 21% of the labor force in Switzerland.

Unemployment by citizenship

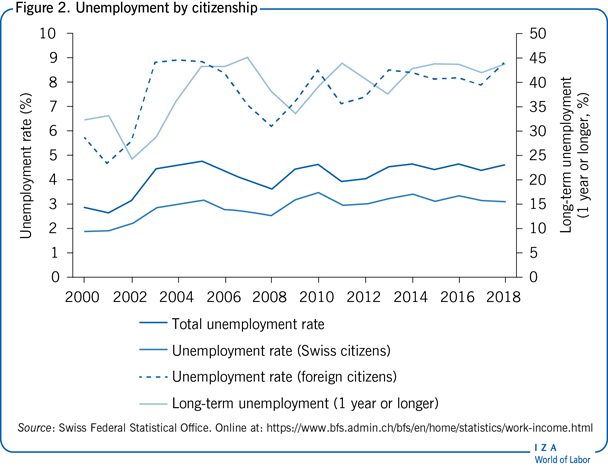

The Swiss labor market has managed to absorb this massive immigration quite well. The unemployment rate has remained stable over the period 2000−2018 (Figure 2). After reaching a low point in 2001, unemployment returned to its mid-1990s level of slightly above 4%, where it has more or less remained until today. The rise in unemployment between 2001 and 2003 coincided with a longer period of stagnation. The unemployment rate increased once again following the financial crisis in 2008. However, this increase was below 1 percentage point, which is low by international comparison. Since then, the unemployment rate has remained generally steady, which is rather remarkable, considering the EU's overall weak economic performance and a strongly appreciating Swiss franc burdening the heavily export-oriented Swiss economy.

The unemployment rate of Swiss citizens has been about 1 percentage point lower than total unemployment throughout the observation period (Figure 2). In contrast, the unemployment rate among foreign citizens has been about twice as high as total unemployment and was close to 9% in 2018. A potential reason for this is that foreigners are overrepresented in low-skilled occupations, where unemployment rates in general are higher. Foreigners might also suffer from greater frictions in the labor market because of lower language proficiency. Figure 2 shows that there has been greater variation in the unemployment rate among foreigners than among Swiss citizens. A possible explanation is the overrepresentation of foreigners in cyclical sectors such as the construction industry. This could also explain the hike in foreigners’ unemployment rate from 2002 to 2003. While this particular increase coincided with the introduction of the free movement of people with the EU, Figure 1 provides no evidence of a massive influx of foreign laborers in that period. Therefore, a positive supply shock of foreign laborers cannot explain the increase in unemployment from 2002 to 2003. Moreover, foreigners’ unemployment rate was already around 8% in the mid-1990s which lends further credence to the explanation that the unemployment rate increase between 2002 and 2003 was due to the weak economy rather than an increase in labor supply.

The long-term unemployment rate, the share of the unemployed who have been searching for a job for one year or more among all the unemployed, is an important indicator of labor market performance. This rate can be high in countries with low unemployment due to low inflow into unemployment. For Switzerland, the long-term unemployment rate was stable at around 30% throughout the 1990s before rising by 10% between 2001 and 2005. Despite Swiss labor market reforms in 2003 [1] and 2011 [2], which incentivized early return to work by reducing possible benefit duration for certain groups, the long-term unemployment rate never recovered and exceeded the OECD average of 29% in 2018.

Labor force participation by citizenship

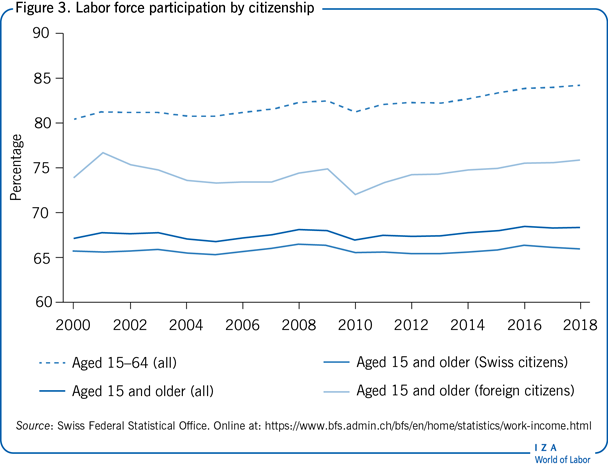

After increasing slightly throughout the observation period, labor force participation in Switzerland for those aged 15 or older was among the highest of all OECD countries, reaching 69% in 2018 (the OECD mean in 2018 was 61%). The picture remains the same when only considering the population aged 15−64, just below Switzerland's current retirement age of 65. Of this age group, 84% participated in the labor market in 2018, which is the second highest proportion OECD-wide (after Iceland).

Figure 3 shows that labor force participation among foreign citizens is about eight percentage points higher than among Swiss citizens. After accounting for the higher proportion of unemployed among foreigners, the proportion of foreigners actually working is still about 4 percentage points higher than the proportion of Swiss citizens working. The reason for this difference largely lies in demographics. OECD studies have shown that the labor force participation rate for those between the age of 15 and 64 in Switzerland is about the same for people born in Switzerland as it is for people born abroad [3]. This finding suggests that the share of foreigners below the regular retirement age of 65 is comparably high, leading to a higher labor force participation rate.

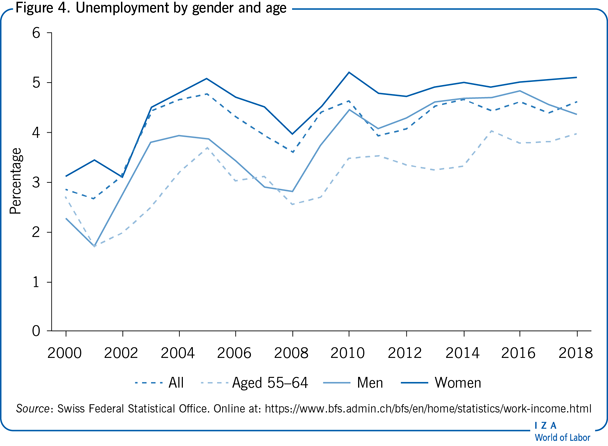

The gender gap and unemployment

Figure 4 shows that men are somewhat less likely to be unemployed than women. However, gender differences in unemployment have dropped considerably in Switzerland during the past 20 years. While women were about 1 percentage point more likely to be unemployed than men between 2003 and 2008, the difference had narrowed to about 0.5 percentage points by 2018.

Women and men aged 55−64 have the lowest unemployment rates, even lower than the unemployment rate of men overall. These low unemployment rates of older workers are because of lower inflow into unemployment, but those who do become unemployed grapple with very long unemployment durations.

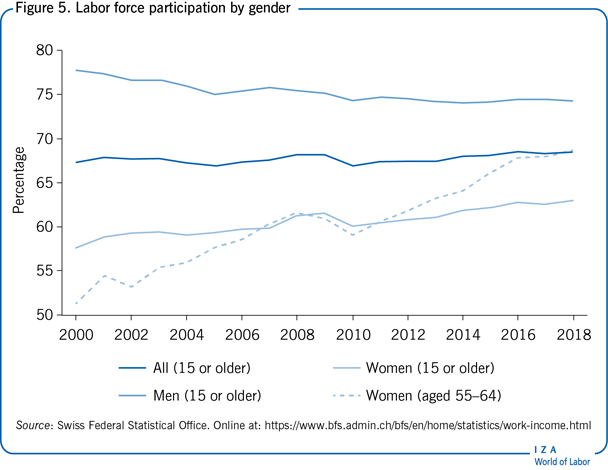

Gender gap in labor force participation

Labor force participation by gender and age is shown in Figure 5. Men are much more likely to be in the labor force than women. In 2000, 57% of women were in the labor force, compared to 77% of men, a gap of 20 percentage points. By 2018 this gap had narrowed to 11 percentage points, both because men left the labor force and because women entered it. Women aged 55−64 entered the labor force most strongly. In 2000, about 51% of women in this age bracket were active in the labor market. Only 18 years later, 69% of women aged 55−64 were active. Increased labor force participation of older women can be attributed to slow-moving factors affecting their labor participation decision such as changes in family norms or increased desire for self-empowerment, but also, plausibly, to policy changes. Switzerland increased the full retirement age (the age at which a pension can be drawn) for women retiring in 2001 from 62 to 63, and for women retiring in 2005 from 63 to 64 [4]. The narrowing gender difference in labor force participation masks a sizable gap in hours though. In 2018, 59% of all women worked part-time, while part-time work is not very common among men (only 18%).

The OECD argues that a “well-regulated labor market” explains the simultaneous high labor force participation and low unemployment in Switzerland [5]. The good economic and institutional framework conditions in Switzerland are another reason. Culture may also play a role, especially compared to other European countries. People in Switzerland may value more highly the status of having a job for non-monetary reasons such as social acceptance and self-esteem [6].

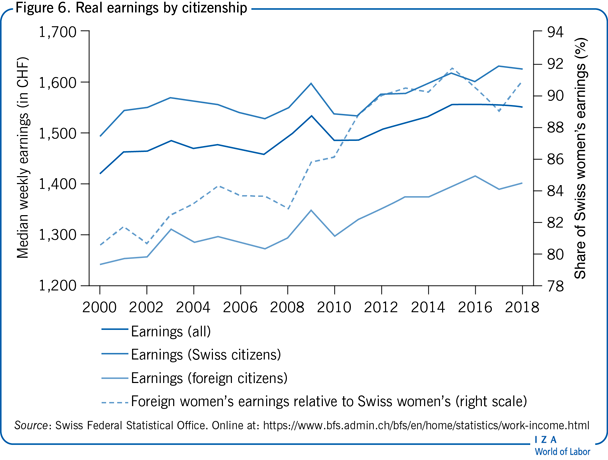

Earnings inequality by citizenship

Median weekly earnings are a good indicator for measuring the development of wages within an economy. As can be seen in Figure 6, real median weekly earnings in Switzerland have grown relatively smoothly, resulting in a total growth of 9% from 2000 to 2018. The only stronger contraction took place after the financial crisis from 2009 to 2010. However, the labor market recovered quickly, with median earnings already back to their pre-crisis level by 2012.

Figure 6 also shows how foreign citizens’ and Swiss citizens’ median weekly earnings have developed. While running roughly parallel until 2008, the growth of foreigners’ earnings was stronger after the financial crisis. This has led to a narrowing of the wage gap between foreigners and Swiss citizens. Women's earnings have been the major driver of this, as the rise in foreign women's earnings relative to Swiss women's earnings shows. The narrowing wage gap between foreign citizens and Swiss citizens is consistent with data showing that since 2000 the level of education of foreign citizens has increased slightly more than that of Swiss citizens.

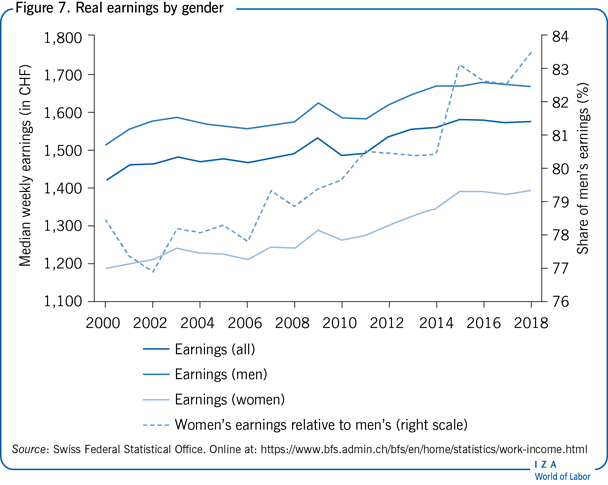

Earnings inequality by gender

Median weekly earnings of full-time workers by gender are shown in Figure 7. In 2000, men earned about 1,500 CHF per week, while women earned around 1,200 CHF, about 80% of men's earnings. Over time, the gap in earnings closed somewhat. Women earned more than 83% of a man's wage in 2018. However, convergence has been slow. At a speed of 3 percentage points per 18 years, or 1 percentage point per six years, it would take another 100 years to wipe out the gender pay gap.

While median earnings are informative about developments at the midpoint of the earnings distribution, they do not say anything about how high or low wages have developed. A conventional indicator for low-paid workers’ earnings is earnings at the first decile (the tenth percentile of earnings) of the distribution of earnings. Earnings at the first decile (not shown) have changed almost in parallel with median earnings, amounting to 66% of median earnings in the year 2000 and 67% in 2016. At the other end of the distribution, earnings at the ninth decile have grown slightly more rapidly than median earnings. They amounted to 173% of median earnings in the year 2000 and 178% in 2016. Switzerland is among the countries with the lowest wage inequality in the OECD. On average, earnings over all OECD countries at the first decile amounted to 59% of median earnings and earnings at the ninth decile amounted to 201% of median earnings in 2016.

Regional differences in unemployment

Switzerland is small, but separated by topographic and cultural (linguistic) divides. Unemployment rates for seven large economic regions within the country are shown in Figure 8. These seven regions can be grouped into two clusters. The first cluster consists of the Lake Geneva area, predominantly French speaking, and Ticino in the south, predominantly Italian speaking. The second cluster consists of the five other areas—Zurich, Central, Espace Mittelland, East, and Northwest—and is predominantly German speaking. The Lake Geneva-Ticino cluster has a higher unemployment rate in every year between 2000 and 2018. Initially, the difference was about 1 percentage point, but it widened to about 3 percentage points by 2018. Labor force participation is also lower in the Lake Geneva-Ticino cluster than in the rest of Switzerland.

The two clusters differ in economic terms. For instance, Lake Geneva-Ticino is more service oriented than the second cluster, which explains some of the differences. However, a recent study shows that the unemployment differences also arise at the language border between French- and German-speaking regions that lie within the same cantons and economic areas [6]. This suggests that some of the differences in economic outcomes may be caused by cultural differences.

Limitations and gaps

It should be emphasized that the results presented in this article are based on raw data, without any adjustments. However, characteristics like education, industry, and family status certainly affect whether an individual works, or not, and how much that individual earns. Accounting for these characteristics is thus crucial for interpretation and might increase, or decrease, the gaps in outcomes by gender or citizenship.

Summary and policy advice

The Swiss labor market has proven resilient to several large shocks during 2000−2018, for example, the Great Recession in 2008, a massive inflow of foreign workers, and a sharp appreciation of its currency. Despite these challenges, unemployment remained stable, and real wages have been on a steadily increasing path. However, differences in labor market performance across regions and between genders continue to arouse concern.

Switzerland should maintain the policies that have supported this resilience, such as its flexible labor laws, and should resist new policy proposals that may endanger it, such as a high general minimum wage. Policymakers should maintain the active strategy to help job seekers find jobs, and develop new tools to reverse the upward trend in long-term unemployment, perhaps by giving job seekers access to information that would help in job search. With culturally driven heterogeneity in labor market outcomes, Switzerland should aim for policies that support convergence, but should be prepared to accept heterogeneity in outcomes. Policymakers should investigate the recent narrowing of the wage gap between Swiss women and foreign women, as it could provide a recipe for improving foreign men's labor market performance or for reducing the overall gender gap in the labor market.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the content and figures to 2018.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed thes principles outlined in the code.

© Rafael Lalive and Tobias Lehmann