Elevator pitch

The number of people holding non-traditional jobs (independent contractors, temporary workers, “gig” workers) has grown steadily as technology increasingly enables short-term labor contracting and fixed employment costs continue to rise. For many firms that need less than a full-time person for short-term work and for many workers who value flexibility this has created a great deal of surplus. During slack economic periods, non-traditional work also serves as an alternative safety net. Non-traditional jobs will continue to become more common, though policy changes could slow or accelerate the trend.

Key findings

Pros

Workers and firms in the independent labor market largely choose independent work because of the flexibility it accords.

The app-enabled gig economy has grown dramatically in recent years, particularly at the low end of the skill distribution.

The gig economy serves as an alternative safety net for some workers in times of economic downturn.

Independent work is a potentially good way for many people to ease into retirement.

Cons

It is very difficult to measure the size of the gig economy (and the independent workforce, more generally).

Non-traditional work imposes risk on workers in terms of fluctuations in income and worry that future “gigs” will not materialize, thereby effectively transferring risk from employers to workers.

Taxation and worker protection policies create both advantages and disadvantages related to traditional vs independent work, which are hard to quantify.

While the value of flexibility might be particularly high for women, women do not make up a disproportionate share of independent workers, and a gender pay gap persists on gig platforms.

Author's main message

Non-traditional work relationships (“independent work”) have grown steadily in developed economies as it has become easier to break work into discrete blocks. The app-based “gig economy” has increased that growth but has not brought (and will not soon bring) fundamental change in most people's work and in the economic centrality of the “employment” model. Independent work is likely to continue to grow as it becomes easier to arrange short-term labor contracts. Policymakers should carefully construct laws and regulations that allow firms and workers to engage in employment relations that maximize efficiency.

Motivation

The rise of Uber and other app-based “gig” platforms, as well as the massive accompanying press coverage, has led to a widespread perception that traditional employment is being overtaken by a “free agent” labor market. Accurate statistics are hard to come by, though, as traditional labor statistics are not well designed to capture people in independent workforce jobs.

While most independent workers choose short-term arrangements because they value flexibility, others take on gigs because they cannot find a desirable traditional job. Understanding the preferences of workers and firms for flexible and short-term work arrangements is important both for planning purposes and for policy. Proper planning can lead to gig work that provides flexibility to those who value it highly while also providing an “alternative safety net” to people looking for their next traditional job.

Discussion of pros and cons

The value of flexibility

Most people who work in platform-based gig jobs and other independent work relationships (such as temporary or independent contractor work) report that they do so by choice. That is especially true in the current worldwide full-employment economy where full-time traditional jobs are readily available and labor is in relatively short supply. According to one 2018 estimate, 78% of independent workers in the US preferred being independent to holding a traditional job. That percentage has gone up steadily in recent years as the unemployment rate has fallen and the traditional labor market has swallowed up those who want a traditional job.

As one example of the value of flexibility, consider one of the largest populations of gig workers—Uber drivers. In a given year, over a million people drive for Uber in the US, though many of them do not last very long on the platform. A recent study shows that, while earnings for Uber drivers are not very high, those who work on the platform regularly for an extended time earn considerable economic surplus from the fact that they have full control over their hours and location of work [2]. The flexibility of Uber allows these people to earn money whenever the opportunity cost of their time is low.

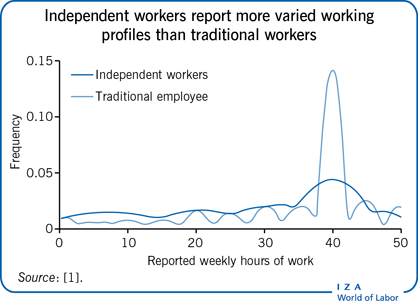

The Illustration shows that the flexibility of independent work leads to much more variation in weekly hours for independent workers than for traditional workers. Independent workers are far less likely to report 40 hours of work per week and more likely to report any other number of hours.

The value of flexibility is very heterogeneous, however. While many Uber drivers highly value it, one recent assessment of the value of flexibility for applicants to a more traditional job showed that most people put no (or even negative) value on the ability to set their own hours [3].

For employers, the value of flexibility is perhaps most crucial to small and growing organizations that cannot commit to a full-time hire or are not sure what their needs will be in a year or two. The world's largest online freelancing marketplace, Upwork, surveyed those who bought labor services on its site in 2014. They report that 80% of respondents had ten or fewer employees [1]. These firms use the site to hire people on a contract basis to do tasks such as web design and search engine optimization because they cannot justify a full-time hire and their needs for such a person vary over time.

Larger firms are also slowly increasing their use of flexible staffing. Upwork, for example, has focused more of its recent business on “enterprise” (large corporate) clients. As technology has made it easier to communicate with remote contractors, many larger employers find flexible staffing valuable for project-oriented work.

Growth of app-based gig work

While internet-mediated freelance work dates back to at least the founding of Elance in 1999, app-based platforms have arisen in the last decade. Ride-sharing apps, primarily Lyft and Uber, have grown from almost nothing in 2012 to over a million drivers in the US in 2018. Other gig economy platforms have grown, though at a slower pace. The distinction between the explosive growth of ride sharing and other types of gig work can be easily understood in the context of a basic search model.

Uber and Lyft assign drivers to those who want to purchase their services. Labor on these platforms is essentially a commodity because the basic service is the same no matter what driver is assigned to the passenger. There are no search frictions because an algorithm (to a first approximation) assigns the nearest driver to each passenger without taking the characteristics of drivers and passengers into account.

TaskRabbit, Upwork, and Fivver, on the other hand, introduce buyers and sellers of labor (rather than assigning them). Someone who wants to have their furniture assembled, translation done, or needs computer programming will be presented with many possible providers of the relevant service. Even if the buyer was willing to just take the first seller presented, that person may not be available at the right time or willing to do the work. So there is a non-trivial matching and vetting process where buyers and sellers of labor negotiate the task to be done, the timing, the price, and other details. Both sides have to be wary of incomplete contracts and the hold-up problem. As a result, much of the potential gain from trade can be dissipated in the matching process [4].

Despite much experimentation, these matching sites have not made great progress in reducing the search frictions that have inhibited their growth. However, as firms gain experience with online freelancers, they learn to hire more quickly and effectively [5]. So there is reason to expect non-commodity remote work to grow as employers gain the skills necessary to use this labor source effectively.

Policy and the gig economy

Policymakers around the world are finding the need to adapt to the growth of the gig economy. Restrictions on rideshare apps, especially related to classification of drivers as employees or contractors, dominate the headlines, but the range of issues and affected workers is much wider. Policy challenges vary across countries due to large differences in social programs and institutions. For example, the relationship between health care coverage and the gig economy is an important issue in the US, but not in countries such as the UK and Canada that have single-payer health care systems. For the purposes of this discussion, the focus here is on the US, but the broad principles apply globally.

One challenge in regulating the gig economy landscape is that workers are highly heterogeneous, varying in age, income, and education in a manner that is surprisingly similar to the traditional workforce [1]. Even within certain segments, workers vary dramatically in the time they spend working. Many Uber drivers work the equivalent of a full-time job while others work a few hours here and there. Drivers leave the platform for weeks at a time and then reappear. Crafting regulations that treat fully committed and occasional gig workers as one group is unlikely to be an efficient solution.

One common justification for strictly regulating independent work relationships is that firms have marginalized gig workers and exploit them. The underlying idea suggests some sort of monopsony power on the part of gig platforms—where a single party substantially controls the market—and, given that platforms seem potentially able to monopolize a specific vertical application of the gig economy (such as rideshare or shift work), this is an important consideration for regulators. At this point, this does not seem like a critical issue given that competition for rideshare drivers, delivery people, freelance workers, and others who find work through apps is quite vigorous and earnings vary with supply and demand.

In the absence of market power by those who hire gig workers, pay should equilibrate so that the marginal worker will be indifferent between gig work and traditional employment (with inframarginal workers strictly preferring one model or the other). There is some evidence that independent workers earn a premium in terms of hourly pay, which is consistent with a compensating differential in place of some of the benefits that go with traditional employment [1], [6]. However, these same studies show that independent workers earn less per week or per year. This is not problematic under the assumption that these workers choose to supply less labor than those in traditional jobs (which is likely given that most independent workers say they prefer independent work to traditional employment). On the other hand, some independent workers may earn extra per hour but not be able to work as many hours as they would like to or find they must spend considerable unpaid time finding work.

As with the broader population of US workers, where concerns about monopsony power have risen in recent years, policymakers should protect independent workers from exploitation [7]. However, as of now, there is not a lot of evidence to suggest such exploitation is widespread or requires new policy initiatives.

Benefits are another area where policymakers should work to ensure parity for independent and traditional workers. The employment-based US health care system makes traditional employment valuable as a source of consistent and sometimes generous health coverage. Independent workers have to purchase insurance through the open market, which can be expensive and time consuming. This is less of an issue for many independent workers who either hold a traditional job in addition to their independent work or have a partner who does. The disadvantage faced by independent workers in the health care market is similar to that faced by any self-employed or unemployed person. Policy aimed at easing access to health care for any worker whose employer does not provide coverage would be of value, though the issue is much broader than helping independent workers.

The right policy for other benefits, such as disability insurance and retirement benefits, is complicated by the fact that workers in the gig economy vary in income, age, and the amount of time spent working. It seems most efficient for policymakers to allow workers to set up their own benefits programs with their own earnings to meet their own needs and then to ensure portability. SEP-IRA's (a type of retirement savings account) already provide independent workers tax-preferred retirement benefits similar to those enjoyed by traditional workers, and these plans can easily be tailored to the income and savings needs of any given individual.

The most contentious regulatory question in the gig economy (in the US, but also in many other countries) is whether to classify independent workers as “employees” or continue to allow platforms and others that engage these workers to maintain a less formal relationship. As noted, in equilibrium if they have no monopsony power, the platforms have the incentive to choose whichever status is most efficient for them and those who provide services through their platforms. However, the variation in workers on these platforms may make it sensible to have some (relatively unattached) workers who are independent contractors and some (full-time or near full-time) who are employees.

Unfortunately, the fear of having all workers classified as employees has discouraged some platforms from providing opportunities to pool purchases of benefits and services such as tax help, insurance of various types, and retirement benefits. Policy that makes classification less contentious and leads to more efficient self-selection should be a primary goal.

Older workers and the gig economy

An important trend across the developing world is its aging population. There is a connection between changing demographics and increased gig work, in that working in the gig economy seems like a natural way to ease into retirement. However, there is not yet much evidence to suggest this is a significant trend. Independent workers are, if anything, a bit younger on average than traditional employees [1], [6]. On Uber, for instance, there are few drivers over the age of 60 [8].

One factor that can limit transition from traditional employment to gig economy work to full retirement is the different contract types. Many older workers are reaping the benefits of an implicit contract (a voluntary and self-enforcing long-term employment agreement) with a steep age/wage profile, during which their earnings have risen considerably as they have aged. However, the market for independent workers approximates a “spot” labor market (with surplus supply leading to contracts when there is demand) where people are paid according to what they add to production, their “marginal product.” As older workers decline in productivity, they can suffer the double hit of lower pay due to lower productivity and lower pay due to dropping from the “overpaid” part of an implicit contract to earning their marginal product.

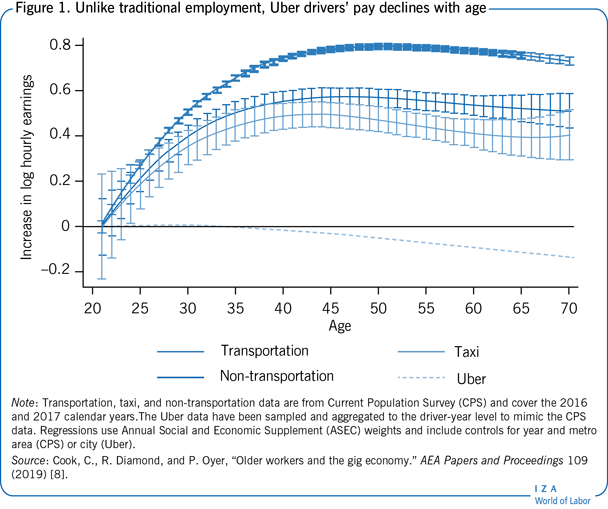

In at least one gig economy context (Uber), a recent study shows that older workers are, in fact, noticeably less productive (and, therefore, less well paid) than their younger colleagues. In addition, Figure 1 shows that the age/earnings profiles for male Uber drivers are markedly different than for all male non-transportation workers, transportation workers, and even taxi drivers [8]. The figure shows that normal career trajectories do not apply, at least not for workers on this one gig platform.

The Uber results suggest that older workers transitioning to the gig economy might face a lower replacement rate of their prior income than they would like. However, the benefits of at least some income replacement and of feeling productive and busy may make the total economic value of transitioning to the gig economy high for many older workers. It should be noted though that the Uber results may not apply in higher skill situations, so further research is needed to draw broader conclusions about older workers in independent work.

The unknown size of the gig economy

Different surveys and researchers have made vastly different claims about the size of the gig economy and the independent workforce more generally. In the US, surveys by the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) are the most heavily relied upon for labor market information. However, while the gig economy has grown, these organizations have not updated their survey instruments accordingly.

The Current Population Survey for many years had an occasional “Contingent Worker Survey” (CWS) supplement to ask about non-traditional employment relationships. This survey was discontinued in 2005 and was always somewhat problematic because it focused on a worker's “main job.” As a result, people who supplemented a traditional job with freelance work were not included. A study from 2015 found that between 2005 and 2015, the fraction of non-traditional workers had increased by about 50% and that, as of 2015, less than 0.5% of the US workforce's primary employment was in the internet-mediated gig economy.

In 2017, the BLS revived the CWS and found much less growth in independent work than was found in the previous study. The BLS concluded that non-traditional work had not grown substantially from 2005 to 2017 and had, in fact, declined slightly. This was partially a matter of labor market conditions (the extremely tight labor market in 2017 meant very few people worked independently if they did not want to) and partially differences in samples across the two surveys. But the bottom line is that, when looking strictly at “main job,” the rise of non-traditional work has not been nearly as dramatic as media coverage of the gig economy might suggest.

Another recent study shows that US statistical surveys are not successfully capturing the rise of independent work. There are hard to reconcile patterns in self-employment (declining) at the same time as independent work has been on the rise. The study concludes, regarding measurement of gig economy work, “Even in these early days, it is clear that the conceptual and measurement challenges are substantial” [9], p. 360.

Other surveys that ask people about any independent work (including occasional work and work in addition to a traditional job) suggest that the fraction of US workers who do gig or independent work in a given year is a quarter to a third of all workers [1]. In a given week, the fraction is likely to be much lower (which is a large driver of the CWS's lower estimate).

All indications are that independent work has grown, but slowly and steadily, as a fraction of the US workforce. However, traditional employment remains the overwhelmingly dominant model for the vast majority of work done by the vast majority of people. App-enabled gig economy jobs have grown quickly, but are not a major part of the workforce overall. As the ability to match short-term jobs efficiently through the internet continues to get easier, statistics agencies need to update their survey methodologies to capture the growth and importance of independent work.

The risk of independent work

The biggest downside of non-traditional work arrangements is the transfer of risk and volatility in earnings from a relatively risk-tolerant party (an employer) to a risk-averse party (an individual). Independent workers have more volatile earnings, week-to-week, than traditional workers. Much of this variation is by choice and reflects the flexibility that is a positive attribute of independent work. Moreover, many independent workers hold a traditional job or have a partner who does, so they are able to weather the ups-and-downs of income variability.

There are no data sets that capture week-to-week or month-to-month variability in income accurately for a large sample, so it is difficult to determine the magnitude of income variability for a set of independent workers. In one recent survey, the majority of independent workers said that “unpredictable income” and “difficulty finding more clients or projects” were “very concerning” or “somewhat concerning.” Press coverage has highlighted these issues on a more anecdotal level, quoting many independent workers who worry about finding their next gig and about the volatility of their incomes.

While week-to-week variability of income is clearly a bigger issue for independent workers than for those in traditional jobs, it is an important open question as to whether traditional or independent workers are more at risk of the adverse effects of macro shocks. Economic downturns likely put much more pressure on the typical independent worker, leading to less available work and pressure on the rates they can charge. On the other hand, during significant downturns, many traditional workers lose their jobs and, as a result, all their earnings. As many studies have shown, job loss often leads to long-term negative consequences due to substantial periods of unemployment and/or lower wages (and maybe reduced hours) upon finding another job. Independent workers are less subject to these extreme losses.

While choosing between traditional employment and independent work generally involves risk considerations, the availability of independent work lowers the risk for all workers by providing an “alternative safety net.” Rideshare availability has been shown to increase short-term consumption and earnings when other sources of earnings drop, suggesting that the ability to become a rideshare driver quickly provides insurance to low-skill workers [10]. Once more detailed data are available on independent workers’ earnings, a fruitful area for research would be to measure the relative riskiness (in terms of macro shocks) of independent and traditional work.

Tax policy and tax collection

An important policy issue regarding the gig economy is taxation. Ideally, tax liability on income earned through independent work and through traditional employment would be roughly equal, so that taxes would not distort the choice of how employers and workers contract.

As an example of where this should not present a major problem, consider Social Security (payroll) taxation. In traditional jobs in the US, the employer pays half the Social Security tax and also collects half of the tax from the employee before paying wages. Independent workers pay the full tax themselves, so it would be expected that independent workers would get paid more to compensate for this higher tax burden. Having independent workers pay the tax themselves is efficient, because they may hold a traditional job or get paid a large amount across many independent contracts. Given there is a per-worker cap on total Social Security taxes, the worker thus has the proper incentives to manage the tax payments.

While that may work well in most cases and for most independent workers, there is the issue of tax avoidance and/or taking advantage of tax breaks through independent work that are not otherwise available. In the US, firms that pay independent workers are required to file a form 1099-MISC or 1099-K with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Different gig economy platforms have interpreted the requirements differently (often changing from year to year). For example, Lyft and Uber only sent 1099-MISC forms reporting driver earnings to the drivers and the IRS for drivers who earned at least $20,000 in 2018 and completed at least 200 rides. Most drivers do not meet these criteria. While each driver has an obligation to report earnings to the IRS even if no 1099-MISC is issued, it is unclear what fraction of drivers honor that obligation. Other gig platforms follow similar practices. So one interesting area for future research is the extent to which independent workers keep their work spread out among a wide set of platforms and other buyers of their services in order to keep their reported income low and save on taxes. This may be very costly to governments in the form of lost revenue and may distort the choice of whether to work as a traditional or independent worker.

The gender pay gap and the gig economy

The rise of the gig economy has led some to hope that independent work could contribute to closing the gender pay gap. It might be expected that short-term and transactional labor market interactions would minimize gender disadvantaging effects and that, when jobs are more flexible, women would be at less of a disadvantage. However, most relevant studies find that women are not overrepresented in the gig economy—in fact, they are often found to make up a smaller share of non-traditional workers compared to traditional jobs.

Focusing on earnings, two recent studies have looked at gender differences on large gig economy platforms. One study used data from Uber, where an algorithm assigns drivers to riders without taking gender into consideration [11]. Nonetheless, men make 7% more per hour than women on the platform, which can be fully explained by three factors: accumulated experience as Uber drivers, differences in where they drive (primarily due to differences in where they live), and driving speed. The relationship between accumulated hours and earnings for Uber drivers has a similar pattern to that for more professional workers and implies that, whether in the traditional or independent labor markets, men's tendency to work more consistently and longer hours is likely to sustain a gender gap no matter how work is organized.

The second study focuses on a platform that introduces people who need tasks completed to those who can perform those tasks [12]. The work is varied and generally low skill (including laundry, shopping, carpentry, and handyperson services). In some cases, those who are trying to hire people post a wage and take the first person who accepts it. In other cases, people post tasks they want done and then review proposals from those who are interested in doing the work. The authors find that women on the platform sort into jobs that pay less and that they demand less pay for a given job, holding their skills (as measured by evaluations on the site) constant. They argue that, assuming women continue to have lower outside options than men, gender pay differences will be perpetuated in independent work environments.

Limitations and gaps

One of the biggest gaps in understanding the importance of the independent workforce is the lack of solid data on the size and growth of this sector. Traditional labor market surveys are not currently equipped to capture the influence and the growth of the gig economy. Efforts are underway at many agencies to fill this gap. Restarting the CWS in the US was a positive step, though many researchers have noted the limitations of that survey and have identified ways it can be modernized. Other related efforts will also help and, to the extent that countries want to set optimal policy in this area, they should invest in appropriate surveys and statistical work.

Another significant gap involves the gig economy's relationship to the rise in inequality. Press coverage of Uber, Lyft, and other lower-skill independent work platforms tends to present the impression that these platforms are exploiting workers and exacerbating inequality. However, given the absence of evidence that they have substantial monopsony power, it seems more likely that these platforms are more an outcome of inequality than a cause. The growth in inequality has been almost entirely an across-firm rather than within-firm phenomenon, which may indicate that firms that have done well have tried to shed low-skill workers from their formal employment rolls. This strategic outsourcing choice, as well as the high fixed costs of employing workers with generous benefits, may contribute to the availability of low-skill workers for non-traditional employment. While this seems likely to be true, it is also speculative and worthy of formal research.

Summary and policy advice

The gig economy (and the independent workforce more generally) has probably grown steadily in recent years, in large part owing to the dramatic rise of rideshare apps. Despite this apparent growth, there has not been any corresponding substantial decline in traditional employment. Technology has enabled short-term contracting for both in-person work (such as ridesharing) and remote work (such as freelance computer programming and graphic design). This trend is likely to continue to increase independent arrangements between workers and buyers of their services. But the end of formal employment contracts between firms and workers is not imminent.

Allowing those who hire people and those who are looking to supply labor to contract in the most efficient manner should always be the goal that guides policymakers. As the gig economy develops, some policy changes are likely necessary to give independent workers portability of benefits and protection from exploitation. Policymakers should focus on rules that lead to fairness for workers no matter what level of formal employment they may seek. Specific areas for policymakers to consider include leveling the playing field, tax-wise, between various employment models; ensuring that internet-based platforms do not develop monopsony power; and enabling independent workers to access and move benefits such as retirement and health dollars.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author was paid to write a white paper on behalf of Upwork in 2015–2016. He has written papers cooperating with employees of Uber, Inc. and using the company's data, though he has never been paid by Uber.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Paul Oyer