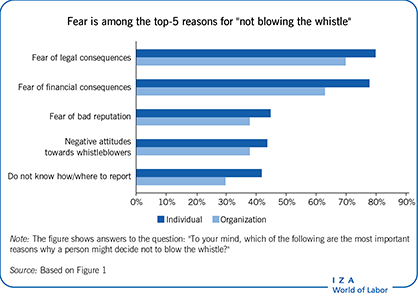

Elevator pitch

Internal whistleblowing refers to the decision of an employee observing a misconduct in a firm to report it through an internal channel, i.e. via a hotline or directly to an identified ombudsman. Whistleblowing is highly beneficial to firms in various ways. However, employees may be reluctant to blow the whistle, both for moral reasons and due to a fear of retaliation. Consequently, a firm aiming at encouraging whistleblowing in order to save judicial or reputation costs, fines, and to spare its reputation should consider a wide range of possible measures in addition to developing a global ethical culture.

Key findings

Pros

Internal whistleblowing procedures reduce the risks of fraud that could damage firms.

Encouraging employees to report internally, along with the resulting reduction of fraud, reduces external whistleblowing to the authorities and thereby allows avoiding fines.

Internal whistleblowing prevents the firm from public whistleblowing announcements to the media that imply negative stock-price reactions and potential shareholder lawsuits.

Wrongdoing that is prevented or quickly corrected enhances working satisfaction and employee engagement. Implementing internal whistleblowing procedures improves the firm’s brand image.

Cons

Employees may misjudge the situation and wrongly blow the whistle.

Internal whistleblowing may challenge the organizational hierarchy and make the organization structure more fragile.

An employee who blows the whistle may suffer retaliation.

Internal whistleblowing procedures are not always efficient and may have counterproductive effects by demotivating whistleblowing.

Author's main message

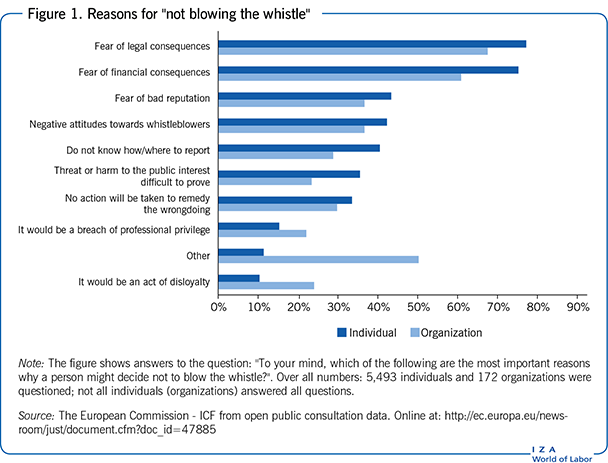

The reasons for not blowing the whistle are numerous. One is fear of consequences. Another is unfamiliarity with whistleblowing procedures and fear that no action will be taken after reporting. These potential negative consequences can easily outweigh employees’ motivations to report a misbehavior, hence there is a need for the firm to be proactive on this issue. In order to encourage their employees to blow the whistle, firms should implement a whistleblowing process by taking immediate actions in case of wrongdoing but also establish a whole ethical culture within the organization, in order not only to solve misconducts but also to prevent them.

Motivation

Illegal or unethical behavior within firms, such as corruption, financial fraud, discrimination both at hiring and promotion stages, sexual or moral harassment, danger to the environment or data breaches, are widespread. To fight such issues, regulations have been increasingly imposed to encourage both internal and external whistleblowing (hereafter, WB). On top of such regulations, firms themselves enable their employees to internally report fraudulent practices. While policy-makers aim to prevent and punish fraud, companies may be hesitant to adopt and implement WB procedures due to concerns about disruptions to their organizational structure and potential stock-price reactions that may follow reporting.

However, companies also recognize benefits, such as their own will to reduce fraud and, in doing so, the risk of being ultimately sued and fined by the regulation authority, but also to encourage their employees to report internally rather than to regulators, which decreases the probability of an external detection. Establishing formal whistleblowing procedures can improve a firm's reputation, increase employee loyalty, and strengthen overall corporate governance.

Given the relevance to implement internal WB procedures, an important topic for firms is to identify the determining factors of decisions to blow the whistle. Employees may be reluctant to blow the whistle for various reasons, such as ethics, loyalty toward wrongdoers or fear of retaliation. Firms have a power of action and can influence the employees’ decision to blow the whistle by taking specific measures, such as establishing clear WB procedures and clearly defining consequences for wrongdoing.

Discussion of pros and cons

Internal whistleblowing is partly imposed by statutes

Countries having whistleblowing statutes are numerous, but the rules that apply may differ a lot from one legislation to another. In any case, some provisions are general and apply to both internal and external whistleblowing, but some are specific to one type of WB.

Focusing on internal WB, some legislation requires firms to implement WB procedures in order to encourage their employees to report a misconduct they have witnessed. Such obligations may be limited to firms of a certain size, defined by a minimum number of employees. For instance, in the US, since 2023, and in the EU, since 2019, an internal reporting channel has to be introduced in organizations that employ 50 employees or more. It is not mandatory in smaller firms. Furthermore, when an internal procedure is imposed by law, an important distinction is the path that a whistleblower must follow in order to report the wrongdoing. In some countries, statutes require that internal WB precedes potential external WB (as in the UK) whereas no such obligations exist in other countries, so that external WB may come first, as in the US, Australia, and France.

There are also fundamental differences in the incentives designed to encourage WB, particularly in terms of protection against retaliation and potential rewards. Statutes may provide for the protection of an employee reporting a wrongdoing internally, but protection measures against retaliation may be limited to some sectors (such as the nuclear sector in the US). Additionally, protection is sometimes denied if WB is done in bad faith (as in the US and the UK). Mechanisms that are provided by law such as rewards for whistleblowers, implemented in order to encourage observers of wrongdoing to report it, generally do not apply to internal WB.

Organizations’ reluctance to implement internal whistleblowing procedures

Managers may sometimes be reluctant to implement whistleblowing procedures because they believe the potential costs outweigh the benefits. For instance, they may be worried that WB, especially when internal WB is then followed with external WB and/or public disclosure of wrongdoing, financially harms the firm, notably via a drop in the stock price [1]. Moreover, one may fear that employees misjudge the situation on which they report, needlessly imposing costs and risking tarnishing the firm’s reputation without justification [2]. Another point explaining the potential reluctance is that internal WB may challenge the firm’s hierarchy, especially when reporting comes from employees at low levels of the firm reporting wrongdoing by employees at higher levels. Though the opposite case is more frequent as WB more often comes from higher-level positions, bottom-up reporting may disturb the internal organization [3].

Why organizations eventually should choose to implement such procedures

One key argument for internal WB procedures is that they encourage employees to report issues internally rather than externally (particularly to the media). External WB impacts firms through several paths. First, a WB announcement may tarnish a firm’s reputation, implying adverse publicity. This translates for firms listed on stock exchange into a fall in their stock prices that can be strong and directly impact the firm’s performance [2]. Moreover, public reporting exposes a firm to the risk of being sued by third parties such as competitors, NGO or associations, and oblige it to compensate potential victims and bear judicial costs, as well as to be directly fined by a regulation authority [4]. Internal reporting, on the other hand, allows the firm to make corrective measures in order to put an end to the wrongdoing before it potentially becomes public. Another argument in favor of encouraging internal WB relates to the fraud preventing effect that internal WB may imply. Fraudulent behavior often leads to significant financial losses for the firm. Moreover, another indirect cost associated with wrongdoing or fraud is that it exposes firms to the risk of sanction by authorities.

Overall, the reduction in the harm caused by the wrongdoer to the firm and in the risk of being fined are allowed both by better practices that WB encourages and by the substitution of external by internal reporting.

Regarding the firm’s reputation, it is important to note that introducing internal WB procedures and making such information public may improve the firm’s brand image. An organization implementing internal WB procedures may attract new customers and employees. Overall, a firm where wrongdoing either does not occur or is effectively and quickly corrected is one where the overall satisfaction is higher and where employees’ commitment is strengthened [4].

Finally, the various measures that can be taken in order to encourage internal WB, such as an ethical culture and a healthy management, are associated with a higher degree of trust within the organization, more motivation from employees, a better leadership, and an ethical climate, which are all factors that translate into a better overall performance of the firm.

Blowing the whistle does not necessarily come spontaneously

Encouraging whistleblowing is challenging, as employees are not necessarily prone to uncovering frauds or wrongdoing. Indeed, employees witnessing wrongdoing face a moral dilemma. On one hand, observers of a misconduct can be motivated by the will to remove the harm or the externality implied by the wrongdoer, which would benefit the firm and society, as well as to be in line with their own values and their unwillingness to feel like an accomplice of the misconduct. Consequently, staying silent imposes a moral cost that could lead the observer to prefer to report the wrongdoing. However, blowing the whistle also implies potentially large costs for them, so that the perceived moral benefits associated with the act of reporting may be cancelled.

A first strand of reasons why an employee might be reluctant to blow the whistle is related to moral aspects, as reporting may be perceived by the whistleblower themselves as morally questionable [5]. This is even more the case when the wrong behavior comes from a close work relationship, such as a long-term colleague or a direct supervisor. There is evidence of a reduced chance of reporting in such cases [6]. Moreover, both from a moral and reputational point of view, a reporting employee does not want to appear to their colleagues as a "rat". This is reinforced by the fact that WB can be considered as deviant behavior by some members of the organization, who consider the whistleblower as betraying the firm or, at the very least, betraying the wrongdoers. In such a case, the potential whistleblower faces an ethical dilemma, as reporting the wrongdoing may appear both moral and immoral depending on one’s subjective viewpoint.

Another motive that can prevent employees from blowing the whistle stands in the fear of retaliation by wrongdoers [7]. Retaliation may take various forms, from colleagues’ ostracism and decreased quality of working conditions, to moral harassment, career obstacles, and job loss [5]. On top of job loss, employees might prefer to avoid a reputation as a whistleblower outside the firm, fearing that such information reduces their chances to get another job.

Apart from these considerations, research shows that the decision to report wrongdoing depends both on the context and on the individual characteristics of the employee. Regarding the context, employees are more likely to blow the whistle over wrongdoing perceived as more severe, e.g. over financial statement fraud (compared to theft), as well as in instances where the wrongdoer knows that the potential whistleblower is aware of their actions [1]. Individual characteristics are also key elements in the decision of an employee to blow the whistle. Thus, whistleblowers are in the majority of cases one-time complainants. Moreover, whistleblowing is positively correlated with employees’ education level, higher job positions and a high score at tests of moral reasoning. Women are also more likely to blow the whistle [3], [8]. Age and tenure are also found to play a positive role in the decision to report [3], though this result is not unanimously found. Finally, a proactive personality is associated with a higher probability of reporting [4].

The provisions included in external whistleblowing procedures

Whereas external WB procedures are specified by law or by public authorities, the core of internal procedures must be decided by firms. Having a look at external WB, the type of evidence the whistleblower should bring is not specified, except in the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) whistleblower law which stipulates detailed examples of the documents that may be addressed. Most laws (False Claim Act, IRS Whistleblower Law, Leniency programs in the US and the EU) do not allow for anonymous WB, but the authority guarantees in some cases the secret over the whistleblower’s identity. In the US, most laws also include a reward provision that may reach 30% of the recovered amount, which is generally not the case in Europe. Rewards associated to reporting have also been implemented notably by antitrust law through leniency programs, that provide a member of a cartel who reports and proves its existence with an amnesty that may entirely cancel the fine they would have had to pay in case of detection or reporting by another firm.

The specific measures that may encourage internal whistleblowing

Identifying misbehavior is a necessary precondition to reporting it. Employees must be aware of what constitutes illegal and unethical behavior, which can be achieved through regular training. In order then to encourage internal WB, one starting point is to introduce a visible and formal internal channel, sometimes referred to as "perceived channel justice" [8], concretely allowing for blowing the whistle. The identification of a single person, namely an ombudsman, who receives information about breach of law is known to increase internal WB, but the receiver of the complaint may also be the human resources service or the manager of the employee. An additional step that medium-sized and big companies may take is to introduce a hotline, consisting of a specific telephone number or of a software that can be accessible 24/7 and from any location.

Once the wrongdoing has been reported, key steps should include quick acknowledgement to reassure the employee that their concerns are taken seriously as well as confidentiality assurance, ensuring that the whistleblower’s identity remains confidential. The anonymity is easier to guarantee in internal WB than external WB, as firms have to deal with less reports than a national public authority. Studies tend to show that most initial reports are submitted anonymously, making anonymity a crucial aspect of an internal WB procedure.

These steps should be immediately followed by a preliminary assessment in order to determine the validity of the claim and whether it warrants a deeper investigation. If the report is substantiated, the procedure should further proceed with an investigation. When the wrongdoing has been committed by a CEO, then a board of directors is the best option to respond quickly and appropriately by implementing immediate measures [9]. During the post-reporting phase, the whistleblower, except in the case of anonymous reporting, should be kept informed about the progress of the investigation without compromising its integrity. Finally, if the investigation confirms fraudulent behavior, the firm should take immediate corrective actions, including disciplinary measures, and establish a mechanism to protect the whistleblower from any form of retaliation. This can be achieved by keeping their identity secret or by implementing anti-retaliation protections, such as creating a committee dedicated to this risk. Note however on this point that a perverse effect stemming from explicit protection included in hotline policies is that it makes the dangers associated to WB more salient so that such explicit provisions might indeed decrease the motivation of potential whistleblowers to report [10].

Another specific measure that could help encourage the reporting of observed misconduct, which has proven to be an efficient incentive, is the payment of a reward to the whistleblower. In cases of external WB, governments often provide these incentives, as in the US, where whistleblowers receive a portion of the recovered funds as a reward. The empirical studies based on experiments in the context of leniency show that rewarding reporting on top of cancelling the fine substantially increases the rate of reporting [11]. Such a result has also been obtained experimentally regarding employees’ decision to blow the whistle when they are aware of their manager’s misconduct [5].

By comparison with external WB, the implementation of a reward in the case of internal WB might appear more difficult to implement, but there are several ways to achieve it. It may either consist of a direct payment that could be fixed or proportional to the recovered savings if relevant, or translate into a salary increase or a promotion [4], [5]. However, the question of financial rewards must be carefully balanced due to the perceptions associated with accepting such a reward. Depending on whether whistleblowers are paid for their reporting or not, the social image they get after the reporting might differ, so that their incentives to report might be affected. What might be perceived as a completely altruistic and moral gesture when not rewarded could be perceived as a greedy action when it is remunerated. This argument is in part balanced by the fact that rewarding whistleblowers may also foster a positive social judgment by giving the signal that such an action is desirable and supported by the firm.

Moreover, it is interesting to note that several experimental studies show that WB subsequent to the observance of a misconduct arises even when it is (financially) costly to the whistleblower to engage in reporting [5]. This proves that intrinsic motivation, i.e. due to internal forces driving an individual’s behavior, to report wrongful actions may be powerful.

Note that firms should carefully balance making it easier to report wrongdoing with the need to prevent false reports. Obviously, reporting incentives are negatively correlated with reporting costs. From this viewpoint, not allowing anonymous reporting, or imposing detailed incriminating evidence by increasing reporting costs, should reduce their number while simultaneously deterring false reports.

Note also that the general principles that are mentioned apply not only to fraud, but to any kind of illegal behavior in a firm, including sexual harassment and other forms of physical or verbal violence toward employees. In the presence of such issues however, the approach should be victim-centered and the process should prioritize the well-being of the victim, which includes providing immediate support such as access to counseling services and psychological support. Furthermore, and probably more than for other issues, regular training should be provided to all employees about recognizing such misbehavior, in order to create a culture where such behavior is not tolerated.

Introducing an ethical culture to make a difference

Empirical findings suggest that contextual variables are more powerful determinants of reporting decisions than individual characteristics. Consequently, beyond the previously mentioned specific measures that may help incite silent observers to report, the ethical culture that a firm may develop is crucial to create the context that will make WB more likely.

From this viewpoint, several factors are relevant [12]. The first one is clarity over the expectations of the firm in terms of which behavior is not only legally acceptable, but also desirable from its viewpoint and which is not. A higher degree of clarity is correlated with reporting decisions, as it helps whistleblowers to decide what is expected from them, but also to believe that their reporting will be given appropriate responses. More clarity also allows that observers of a misconduct feel complicit if they choose to remain silent as they do not doubt what is right and what is wrong.

A second determining factor relates to the leadership and the congruency of management, i.e. the extent to which the firm’s managers themselves apply the standards to their own behavior. When managers lead by example, they help clarify ethical principles and are more likely to earn employees' trust, encouraging them to report wrongdoing. Some types of leadership are especially prone to encourage WB. This is the case of transformational leadership, a form of leadership that heavily appeals to the intrinsic motivation of employees, as opposed to transactional leadership that mainly relies on rewards for meeting objectives. Transformational leadership has proved to increase the employees’ confidence in their ability to report misconduct without fear of retaliation [13]. As some authors suggest, the role of management might also be enhanced though the delivery of training on recognizing retaliation when it is occurring and knowing how to react is absolutely necessary for quick measures to be taken.

In line with the two previous factors, the responsiveness of the management to wrongdoing, referred to as sanctionability, appears as a key part of an ethical culture. An unpunished misconduct would leave a whistleblower with the feeling that wrongdoing is possible, and potentially desirable. Thus, the correction and termination of wrongful actions appear to be important predictors of the decision to report, whereas on the opposite, witnessing actions that are not followed with sanctions decreases the probability of reporting because it is associated with diminished perceptions of organizational support and channel justice [8].

These factors boost a whistleblower's confidence by aligning their actions with management's values and fostering social approval through an ethical culture. A vast experimental literature analyzing the psychological underpinnings of behaviors highlights the role of social judgment in the decisions of individuals to take a given action. For instance, it is shown that the contributions of individuals in public goods are strongly affected by their peers’ observation of these contributions. The simple observation of contributions helps increase their average level, and the possibility to sanction the lowest contributors further enhances cooperation. In a WB decision, the potential for social judgment, especially when anonymity is not guaranteed, impacts decisions. If misconduct is publicly observable, whistleblowers are more likely to report, anticipating social approval [5]. Thus, it is crucial, when reporting is not anonymous, that a firm’s culture ensures that potential whistleblowers feel that their actions will be socially supported.

Limitations and gaps

On the question of internal WB, most empirical studies (about 60%) are based on surveys that study the intentions of respondents to blow the whistle in various hypothetical scenarios [6]. This method is prone to "hypothetical bias", i.e. the gap between the individuals’ declaration about how they would behave, and their actual behavior. While these surveys identify correlations, their predictive accuracy in real situations especially on sensitive issues such as WB is questionable. Experiments, which represent about 20% of studies, place subjects in a context where their decisions have real consequences (in terms of payoffs) for themselves and others. They also isolate the effect of one variable at a time. However, the external validity of lab experiments may also be debatable. Some data analyses are based on real whistleblowing cases and allow investigation of the role of individual characteristics and of some contextual variables on whistleblowing decisions, but they do not allow for the comparison of different incentives. Finally, very few analyses drawn upon interviews have been run, but they are qualitative studies with data that cannot be statistically assessed.

Moreover, most studies on internal whistleblowing typically rely on data from narrow samples that do not represent the entire population. These studies focus on students, specific economic sectors, or particular job roles, such as nurses or managers, rather than a broad cross-section of the workforce. There are a few exceptions, and a few papers use broader samples of the working population of a given country [12].

Future research on this topic might also explore the comparison of the mechanisms behind WB intentions and actions depending on whether they occur in the public or in the private sector. Whereas one might expect WB to be more important in the public sector, where job loss (and thus the fear of retaliation) is less likely, countervailing forces might play a role, as private organizations can pull more strings (such as rewards) in order to activate WB decisions. Whereas existing studies focus on either the private or public sector (or include employees from both sectors), an accurate comparison of the various factors intended to encourage internal WB might be useful.

Summary and policy advice

Though firms may be reluctant to encourage internal whistleblowing, because it has long been viewed as challenging the hierarchy and because firms may fear the lost time associated with reporting of actions misidentified as wrongdoing, they should seriously consider implementing WB procedures. On top of the fact that some procedures are imposed by statutes, it is generally in their best interest to do so and go further.

The benefits associated with promoting internal WB are numerous. WB helps prevent or uncover fraud, which reduces direct financial losses for the firm. Additionally, it lowers the risk of fines from authorities and lawsuits by encouraging internal reporting over external WB. This reduces the likelihood of public exposure, which can harm the firm's market value, shrink its customer base, and tarnish its brand. Given these advantages, organizations should prioritize fostering internal WB.

However, employees who observe a misconduct are not necessarily keen to report it, as they face a moral dilemma. On the one hand, they might want to end the wrongdoing that harms the firm, so that staying silent could make them feel like they are approving the wrongful action. On the other hand, observers might anticipate social disapproval from their reporting decision and fear retaliation.

Consequently, to motivate employees to report wrongdoing, organizations should implement specific measures like reporting channels, protection, and financial rewards. However, these must be integrated into a broader ethical culture. Employees need a clear understanding of acceptable behavior, confidence that reports will lead to appropriate sanctions, and assurance that reporting is socially supported. Leadership plays a crucial role, with clarity, consistency, and accountability being key factors in encouraging whistleblowing.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous referee(s) and the IZA World of Labor editors for helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The authors declare to have observed these principles.

© Yannick Gabuthy and Eve-Angéline Lambert

Internal and external whistleblowing

Internal whistleblowing refers to the action of an individual (whistleblower) observing a misconduct, unethical behavior, or any wrongdoing in their company, who decides to report it internally. Such internal reporting may entail notifying a supervisor, a manager, an identified colleague, the human resources department, or an internal whistleblowing mechanism.External whistleblowing involves reporting wrongdoing to individuals or authorities outside the organization, such as government agencies, an attorney, or the media.

Both types of whistleblowing are not mutually exclusive, as internal whistleblowing may precede external whistleblowing.