Elevator pitch

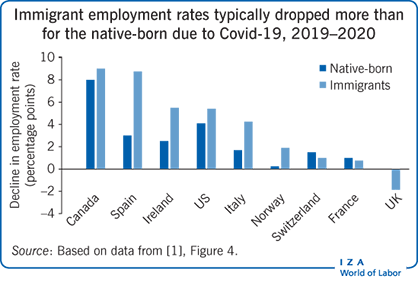

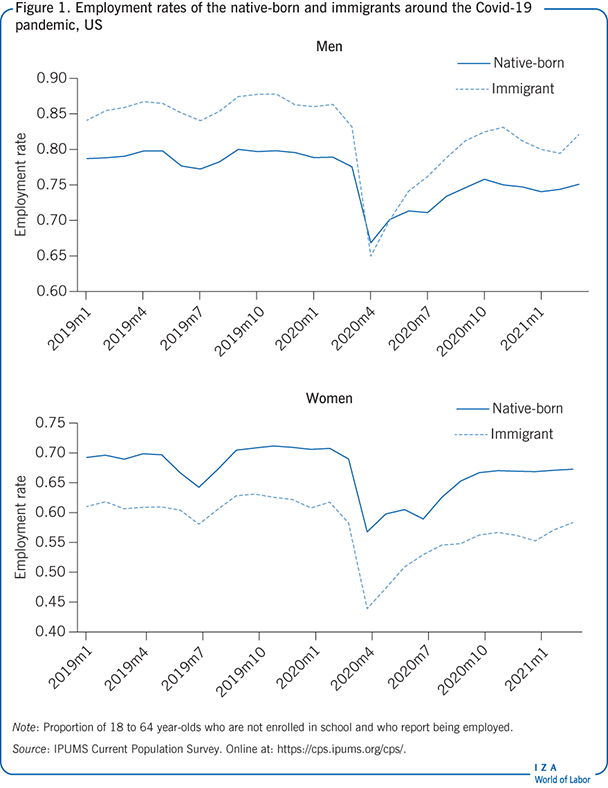

The labor market disruptions due to the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns impacted immigrant workers more severely than native-born workers in the US, Canada, Australia, and most EU countries. Immigrant workers in most of these countries were more vulnerable to the pandemic since they were more likely to be employed in jobs that are not as easy to perform remotely. The labor market recovery for both groups in the US was rapid, and by Fall 2020, the employment gaps between immigrant and native-born workers, both for men and women, had returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Key findings

Pros

Many workers, including immigrants and native-born, were able to successfully continue working from home during the pandemic.

Rapid employment recovery was experienced by natives, but especially by immigrants, in the US and Canada in the months following April 2020.

Work arrangements such as short-time work schemes more common in the EU likely mitigated job loss, especially for immigrants.

No evidence of racial bias in employment loss due to the pandemic was observed in the US.

Cons

Immigrants suffered significantly larger employment declines than the native-born in the early stages of the pandemic in most developed, immigrant-receiving countries.

Lower job remotability of immigrants left them vulnerable to job loss in the early stages of the pandemic.

Immigrants in the US, especially men, faced more difficulty searching for employment due to the pandemic than the native-born.

Immigrants in most developed countries will remain more susceptible to future lockdowns due to their employment in less-remotable occupations.

Author's main message

Immigrant workers in the US, Canada, Australia, and most EU countries were more susceptible to employment loss resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, partly because their occupations are typically more difficult to perform remotely. Though employment recovery in the US was faster for immigrants than native workers, future shocks may again affect immigrants more severely. Though it is difficult to pinpoint specific policy responses to such events, two possible options include enhanced focus on immigrants’ language proficiency, and greater consideration as to how policy responses will impact different groups.

Motivation

Between March and April 2020 (the onset of the pandemic), the employment rate in the US fell from 72.7% to 60.4% [2]; in Canada, it fell from 58.5% to 52.1% [3]. Though not as severely as in North America, employment rates also declined in most EU countries [1]. Unsurprisingly, unemployment rates also rose in many countries: in Australia, from 5.3% to 6.4%, while in Germany, from 5.1% to 5.8%. Lockdowns due to the Covid-19 pandemic affected nearly all workers, though not to the same degree. Especially, immigrants in most developed, immigrant-receiving countries are more likely to work in occupations that are difficult to perform remotely, whereas native-born workers tend to work in more “remotable” occupations. Due in part to this difference in employment patterns, during the early stages of the pandemic, immigrant workers in the US, Canada, Australia, and most EU countries experienced a significantly larger employment drop than native-born workers, for both men and women [1], [4].

In the months following April 2020 employment in the US recovered quickly for both immigrants and the native-born, and by Fall 2020, the employment gaps had returned to nearly pre-pandemic levels [2]. Employment recovery of immigrants in Canada was significant, but less so than in the US. However, differences in occupational remotability between the native-born and immigrants, which is typical across developed countries, will continue to leave immigrants at greater risk of job loss resulting from future lockdowns.

Discussion of pros and cons

Employment and job loss during early recession

As seen in Figure 1, during the onset of the pandemic in the US (between March 2020 and April 2020) the employment loss was unprecedented: from 72.7% in March to 60.4% in April. But these numbers hide the substantial differences in job loss by groups. For men, the employment rate between March and April dropped by 16.0% for the native-born and 28.0% for immigrants; for women, employment declined by 21.5% and 32.8% for the native-born and immigrants, respectively. Thus, the Covid-19 labor market shock—including the lockdowns in response to the virus—appears to have impacted US immigrants especially harshly. Also in other developed and immigrant-receiving countries, immigrants typically experienced greater employment declines than the native-born in the early stages of the pandemic. Between the second quarter of 2019 and of 2020—the early stages of the pandemic—the employment rate of immigrants in Canada fell by around 9 percentage points while for the native-born the decline was 8 percentage points. In Italy, native-born employment fell less than 2 percentage points but fell by 4 percentage points for immigrants [1]. In most EU countries, immigrants experienced a greater reduction in their employment rate in the early stages of the pandemic than the native-born.

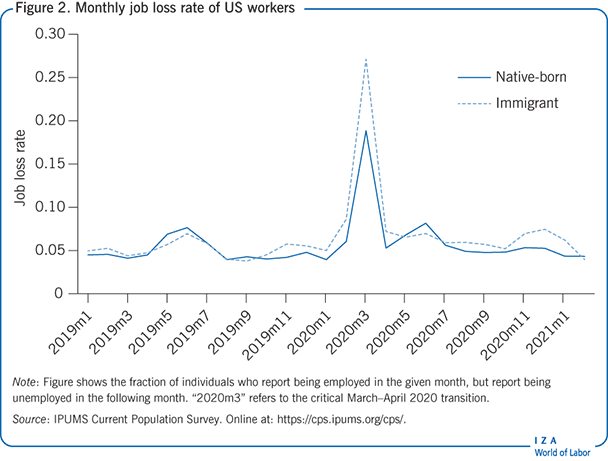

Further evidence of a native-born/immigrant disparity can be observed by looking at the job loss rates between months in the US. Figure 2 shows the job loss rate for the months immediately prior to and immediately following the critical March–April 2020 period. The spike in job loss is clear; also clear, however, is that though the job loss rate between the native-born and immigrants was nearly equal prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, between March and April 2020, immigrants experienced a much greater increase in job loss than the native-born.

Unemployment

The initial stages of the pandemic saw increases in unemployment in most developed, immigrant-receiving countries that were typically greater for immigrants than the native-born [1]. For example, in Norway, immigrants experienced an 8 percentage point increase in unemployment, while the native-born experienced only a 3 percentage point increase. Immediately prior to the onset of the pandemic, the unemployment rate in the US was near historic lows. Immigrant men actually enjoyed an unemployment rate around 1–2 percentage points lower than native-born men, while for women, the rates for the native-born and immigrants were essentially the same. In April 2020, however, 12% of native-born men and 15% of immigrant men reported being unemployed, while 14% of native-born women and 17% of immigrant women reported being unemployed. Thus, consistent with the larger reduction in employment experienced by immigrants than the native-born, a correspondingly larger increase in unemployment among immigrants was also observed.

Direct evidence of Covid-19 and employment

In May 2020, the Current Population Survey (CPS)—the main source of data for US unemployment—added several Covid-19-specific employment questions that are useful for better understanding how the pandemic has impacted immigrants and native-born workers. First, respondents were asked if they were unable to work due to either their employer closing or losing business due to the pandemic. In May 2020, 22% of the native-born and 29% of immigrants reported being unable to work due to Covid-19. Consistent with male immigrants being especially hard hit, while 21% of native-born men were unable to work due to Covid-19 in April 2020, 32% of immigrant men were unable to work. By August 2020, only around 11% of respondents were unable to work due to Covid-19, but a 5 percentage point gap persisted between the native-born and immigrants, suggesting immigrants continued experiencing more difficulty than the native-born in finding work due to Covid-19-related disruptions.

Not only has Covid-19 and the accompanying lockdowns interfered with employment, but job search was also impacted. The CPS asked respondents if the pandemic prevented their ability to look for work. In May 2020, 18% of native-born men and 33% of immigrant men reported being unable to look for work due to the pandemic, while only 14% and 16% of native-born and immigrant women, respectively, were unable to look for work. By August 2020, only 9% of workers reported they were not able to look for work, but an 8 percentage point gap between native-born and immigrant men persisted. Thus, immigrants (especially men) suffered more than the native-born due to the pandemic in both their employment levels as well as their ability to search for jobs.

A third Covid-19-specific CPS question asked if an individual worked from home due to the pandemic. In May 2020, 32% of native-born men and 28% of immigrant men, and 44% of native-born women and 33% of immigrant women, reported working from home. These results are consistent with immigrants working in occupations prior to the pandemic that were less amenable to remote work.

On a global basis, in Ireland, the Labor Force Survey asked respondents who were not at work whether they were “absent due to Covid,” with 21% reporting “yes” [5]. Absence from work due to Covid-19 was more common among immigrants than the native-born, but was especially common among EU-East and Non-EU immigrants in Ireland, suggesting that even within the immigrant group, differences in birthplace appear to be relevant.

Role of remotability

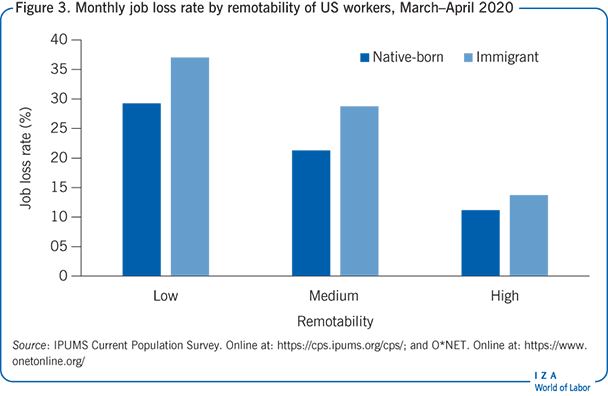

Immigrants and the native-born tend to work in different occupations. Of relevance during the Covid-19 pandemic, immigrants in the US, Canada, Australia, and nearly all EU countries were less likely to work in occupations that can be done at home, that is, that are “remotable,” when the pandemic struck. The importance of remotability has been noted in several recent studies across multiple countries exploring Covid-19 and the labor market [2], [4], [5], [6], [7]. A common finding across countries is that, unsurprisingly, workers who could more easily work from home were less likely to suffer job loss due to the pandemic. Working in less remotable occupations leaves immigrants disproportionately exposed to job loss resulting from lockdowns, and so might help to explain why immigrants typically suffered greater job loss than the native-born at the onset of the pandemic.

For the US, data from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET) was used to construct a remotability index, which measures the ease with which an occupation can be performed remotely. The procedure used occupational characteristics such as the frequency of the use of email and interacting with computers. The occupations were then divided into three groups based on this index: low, medium, and high remotability. While 44% of native-born workers were classified as working in a high remotability occupation in 2019, only 33% of immigrant workers were in a high remotability occupation [2]. In France, around 33% of the native-born but only 25% of immigrants can work from home; in Italy, the gap is much starker: 32% of the native-born can work from home, but only 13% of immigrants [1].

To illustrate the importance of remotability to job loss during the early Covid-19 pandemic, Figure 3 shows the job loss rate in the US by remotability group (low/medium/high) as well as between the native-born and immigrants for the critical period of March–April 2020. Prior to March 2020, little relationship between occupational remotability and job loss existed. As expected, for March to April 2020, there was a significant decrease in the probability of job loss with occupational remotability for both immigrant and native-born workers. However, note that even within the remotability group, immigrants experienced a higher likelihood of job loss, which cannot be explained by differences in remotability level between the native-born and immigrants within remotability groups. Thus, though remotability is an important factor, it alone cannot explain the variation in the immigrant/native-born job loss response to Covid-19.

In Ireland, EU East and Non-EU immigrants were more likely to suffer unemployment than the native-born at the onset of Covid-19. Taking job remotability into account—by measuring low, medium, or high homeworking—helps to explain a portion of this gap in employment loss. Thus, as in the US, Ireland provides direct evidence that differences in job remotability played an important role in understanding why the native-born and immigrants were differently affected in the labor market by Covid-19.

Differences across industries

The pandemic and lockdowns also impacted some industries more severely than others. Immigrants and the native-born differ not only in terms of occupation, but also industry: prior to the pandemic, immigrants were disproportionately represented in sectors especially impacted by lockdowns, such as the hospitality sector (31% immigrant in Canada and 25% immigrant in the EU28), as well as security and cleaning services (30% in Canada and 21% in the EU28) [1]. US immigrants were around 45% more likely than native-born workers to work in the restaurant industry, which suffered significantly from the pandemic and lockdowns, while immigrants were, for instance, underrepresented in the elementary and secondary school industry which, though schooling was heavily disrupted by the pandemic, did not experience a reduction in employment. However, immigrants were overrepresented in the agricultural sector, which similarly did not experience a reduction in employment. Immigrant workers in the EU tended to work in industries considered more “essential” during the pandemic, which to some extent insulated them from job loss [5], [8].

Overall, the importance of industry distribution between immigrants and natives and its effect on employment is inconclusive. In the US, accounting for industry does not contribute significantly to the disproportionate loss of employment faced by immigrants, it does little to shrink the immigrant/native-born gap in job loss. Furthermore, it is unclear to what extent this finding extends to other developed countries.

Race and job loss

Given the origin of Covid-19 in China, there have been concerns that the pandemic could lead to anti-Asian sentiment that might affect the labor market outcomes of Asian workers in immigrant-receiving countries. In the US, where approximately one-quarter of US immigrants identify as Asian, whereas only around 2% of the native-born do, anti-Asian sentiments may help to explain the large native-born/immigrant gap in employment outcomes at the start of the pandemic. However, Asian immigrants in the US did not suffer job loss at a rate different from other immigrants, and both their employment and unemployment rates responded to the pandemic in a similar manner as non-Asian immigrants. Thus, at least in the US, it does not appear that an increase in discrimination against Asians can help to explain the gaps between immigrants and the native-born in their labor market outcomes during the recession.

Work schemes and employee characteristics

Work arrangements differ significantly across countries, and these variations may be informative in understanding how Covid-19 impacted immigrants in different countries. In Germany, short-time work schemes are relatively common, and at the onset of the pandemic, 34% of employees reduced their hours; without this scheme, presumably some of these workers would have otherwise suffered job loss [7]. Such work schemes likely limited job loss, which may have been especially helpful for immigrants as they typically faced a higher chance of job loss. In contrast, employee furloughs (i.e. temporary layoffs) were common in the UK and the US, experienced by 36% and 25% of workers, respectively [7]. Immigrants are more likely than the native-born to be on temporary contracts, leaving them more heavily exposed to job loss than the native-born, who are more likely to be on permanent job contracts [8].

In Canada and Australia, workers with shorter job tenure were at greater risk of job loss [4], [9]. Since immigrants are, when they arrive, new labor market entrants, they often have shorter job tenures than the native-born, leaving them exposed to job loss, especially where work schemes like short-time work are less common and thus layoffs are more attractive to the firm. More recently arrived immigrants in Canada experienced a larger increase in employment-to-non-employment transition early in the pandemic, relative to prior to the onset of Covid-19 [9], which is a reminder that variation among immigrants—in this case, by arrival cohort—rather than just between immigrants and the native-born is also relevant.

Presence of immigrants and the impact of Covid-19 on the native-born

Immigrants can affect native-born workers in terms of labor market outcomes such as occupation, resulting in more native-born working in jobs that prioritize interactive tasks [10]. In EU regions where immigration is relatively high, the job loss suffered by the native-born due to Covid-19 tended to be lower [11]. The mechanism for this effect is that, with larger numbers of immigrants present in a region, the native-born have been able to move into occupations that specialize in interactive-intensive as well as other tasks that are more easily performed from home. As such, one benefit of higher levels of immigrants in a region has been to partly insulate native-born workers from the labor market effects of Covid-19, a result which highlights the complex interactions between immigrant and native-born workers in the labor market.

Recovery phase

Following the unprecedented drop in employment between March and April 2020, both immigrants and the native-born have experienced a steady and significant recovery in their employment levels. However, US immigrants experienced more rapid employment growth than the native-born. As illustrated in Figure 1, by Fall of 2020, the employment gap between immigrant and native-born men had returned to essentially its pre-pandemic level of around 7 percentage points. Similarly, though the employment gap between immigrant and native-born women rose to 13 percentage points in April 2020, by Fall 2020 it had fallen to around 10 percentage points, which is closer to (though still somewhat higher) than typical pre-pandemic levels.

In Canada, immigrant and native-born employment rates began to recover quickly following June 2020, though in Fall 2020, a gap of around 3 percentage points for both groups still existed relative to pre-pandemic levels [3]. As of Summer 2021, employment rates for both immigrants and the native-born had nearly returned to their initial levels. Unemployment rates, however, have remained higher for both groups relative to pre-Covid-19. Even in Summer 2021: for immigrants, their unemployment rate was around 3–4 percentage points higher than before Covid-19, while for the native-born, the gap was only around 2 percentage points. Thus, when comparing these two neighbors, it appears that immigrants in the US enjoyed a more rapid labor market recovery than immigrants in Canada.

As of June 2021, 3.5% of immigrants in the US but only 2.2% of the native-born reported being unable to work due to Covid-19. Thus, while a gap remains between immigrants and the native-born, it has narrowed considerably, indicative of a strong labor market recovery for both groups. Similarly, in June 2021, 2.8% of immigrants reported being unable to look for work due to Covid-19, whereas 1.4% of the native-born were unable to look for work. Again, though much lower than early in the pandemic, a small gap persists.

Teleworking has declined for both immigrants and especially native-born workers since the beginning of the pandemic, but has remained popular for both groups, especially among women. In June 2021, 14.9% of US immigrants and 14.4% of the native-born reported working remotely due to Covid-19. Thus, as of June 2021 there was no teleworking advantage for native-born workers in the US, which suggests that immigrants have been able to adapt to the new working environment.

Have immigrants and the native-born returned to similar occupations during the recovery? One way to assess this is to compare the average remotability of occupations over time. Among those actively working, there was an increase in the average occupational remotability as workers who could not work remotely were disproportionately laid off. As the labor market recovery has progressed, the average remotability of those actively working has declined, though not quite to pre-pandemic levels for either the native-born or immigrants. Currently, it is difficult to tell the extent to which this increase in remotability can be attributed to workers in low-remotability occupations continuing to face difficulty in finding work, or whether a more fundamental change in the labor market has taken place.

Limitations and gaps

This article shows that, in nearly all immigrant-receiving and developed countries, the employment loss experienced by immigrants at the onset of Covid-19 was greater than the employment loss among the native-born. In most countries, immigrants also worked in occupations that were more difficult to perform from home, which may help explain part of their greater employment loss relative to the native-born. Direct evidence from the US and Ireland confirms that the remotability of occupations can help to explain some of the higher job loss among immigrants compared to the native-born; however, even fully controlling for occupation cannot explain all, or even most, of the gap in the employment response between immigrants and the native-born in these countries. A rich set of other controls, including industry, age, education, and state of residence, do little to explain the gap in the US. Thus, researchers are left unable to fully explain why immigrants were more severely impacted than the native-born.

It is worth speculating about some potential causes, both to help guide future research and to better understand the variation in employment responses across groups to shocks. First, employers may favor laying off immigrant over native-born workers, in part due to less firm tenure leading to labor hoarding [4], [9]. Pandemics tend to lead to travel and immigration restrictions as a means of reducing the viral spread, which indeed were common due to Covid-19. Some firms may fear that immigrant workers present a higher risk if their visa status is precarious; however, both citizen and non-citizen US immigrants suffered similarly high job loss at the onset of the pandemic, so this is unlikely to be an important factor. Finally, a lack of dominant-language proficiency among some immigrants might make these workers less able to work remotely, even within the same occupation as native-born workers, leaving them more vulnerable to layoffs.

Summary and policy advice

Shocks to the labor market, such as the Covid-19 pandemic, impact some groups of workers more so than others. Immigrant workers were especially prone to the disruptions caused by the pandemic, due in part to working in jobs that are more difficult to perform remotely. However, the vulnerability of immigrants to the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns cannot be fully explained by their occupation or industry, which suggests other factors cause these workers to face higher risks of job losses from such shocks. Going forward, it is important to better understand why immigrants suffered greater employment losses than native-born workers. Conversely, in the US, immigrants were better able to return to the workforce than native-born workers in the recovery phase, which may be due to large unemployment insurance benefits that have been provided to laid off workers which many immigrants would not qualify for.

One likely consequence of the pandemic is a long-term increase in remote work, a trend that may benefit native-born workers more so than immigrant workers. Understanding why immigrants work in less-remotable occupations is important for ensuring that this group does not miss out on this labor market transition. A likely contributor is a lack of dominant-language proficiency. For example, in the US, English proficiency has been widely known to be beneficial to immigrants’ labor market success [12]; an increase in remote work may further enhance such benefits. As such, government programs that encourage and sponsor language instruction among immigrants will become more beneficial and thus deserve greater attention.

Finally, it is important for policymakers to recognize that actions such as lockdowns in response to pandemics will have disparate effects on different groups. Furthermore, the significant costs of lockdowns will likely be felt most acutely by more vulnerable groups, for example, immigrants, who are least able to bear the cost. Evidence suggests that important racial gaps also exist in the effects of Covid-19 on employment [13]. Significant policy decisions such as highly restrictive lockdowns deserve rigorous cost–benefit analyses that should account for the variation of policy impacts.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author, together with George Borjas, contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in this article [2].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Hugh Cassidy