Elevator pitch

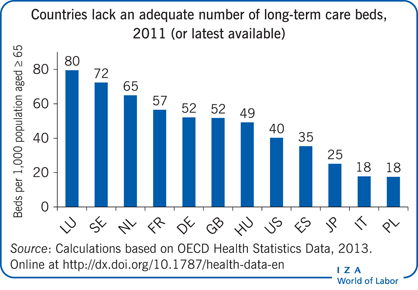

The demand for institutional long-term care is likely to remain high in OECD countries, because of longer life expectancy and falling cohabitation rates of the elderly with family members. As shortages of qualified nurses put a cap on the supply of beds at nursing homes, excess demand builds. That puts upward pressure on prices, which may not reflect the quality of the services that are provided. Monitoring the quality of nursing home services is high on the agenda of OECD governments. Enlisting feedback from family visitors and introducing portable benefits might improve quality at little extra cost.

Key findings

Pros

Portable old-age allowances empower the elderly and thus may help improve the quality of long-term care services.

Many elderly residents in long-term care institutions receive regular visits from family, who can be enlisted to help monitor service quality.

Ombuds systems and adult guardianship could also be implemented more widely to monitor institutional long-term care services.

New forms of nursing home architecture with individual homes for each resident offer more independence and could improve the quality of care and living standards.

Cons

The excess demand for nursing home residence is likely to worsen because of shortages of skilled nurses rather than because of any difficulties caused by regulatory requirements.

Excess demand keeps prices high while offering little incentive to improve the quality of services offered.

Portable allowances, if provided as cash benefits, may be appropriated by relatives of the elderly.

New forms of nursing home architecture with individual living arrangements for each resident can be very expensive.

Author's main message

Under conditions of excess demand, nursing home service providers have little incentive to improve quality. Regulations focus on inputs because outcomes are harder to monitor. One way to improve quality is to empower the elderly to monitor their own care by providing them with a flexible allowance to spend on either institutional or in-home care. Family members and other nursing home visitors could also be enlisted to report on specific indicators of service quality. Recruiting more young men and women to become nurses could ease supply constraints and strengthen incentives to improve quality. All of these options can be introduced at little additional cost.

Motivation

With the number of elderly people in need of care projected to at least double by 2050, “governments are struggling to deliver high-quality care to people facing reduced functional and cognitive capabilities” [1]. The vast majority of beneficiaries of long-term institutional care are individuals of retirement age or older [2]. OECD governments spend about 1.6% of GDP on long-term care, and such spending has been growing at an average of 9% a year over the past decade, compared with 4% annual growth for overall public health expenditures [1]. Longer life expectancy and reduced cohabitation rates of the elderly with next of kin imply that the excess demand for nursing homes is likely to persist in most OECD countries. The problem is exacerbated by a shortage of skilled nurses. Under conditions of excess demand, nursing homes have little incentive to improve the quality of the services they provide. Better monitoring of the quality of institutional long-term care services thus becomes essential.

This paper focuses on institutional long-term care. It does not examine the determinants of the long-term care choices made by the dependent elderly nor does it investigate the scope for substitution between long-term care received at home and that received at a nursing home.

Discussion of pros and cons

The demand for institutional care

There are generally three residential options for the dependent elderly (ignoring the possibility of temporary hospitalization): living with family, living on their own and receiving home assistance, and living in a nursing home. The demand for nursing homes is greater the less capable the elderly are of providing their own care, the better the job opportunities available for women, and the higher the household income [3]. There is limited evidence that the wealthier elderly (who are often also healthier because of the strong positive correlation between wealth and health) have a preference for receiving home assistance over entering a nursing home, which is often viewed as a last resort option [3].

Aside from income, other factors that influence the choice of care options are the availability of public health subsidies (often covering only part of the costs of institutional long-term care) and the extent of family involvement in providing old-age care, which is affected by cultural norms. Early in the 20th century, it was common for elderly people, especially women, to live with their adult children or grandchildren. This arrangement served the interests of the adult child as well, since older women often provided unpaid household services and childcare [4]. However, due to rising incomes and changing cultural norms, co-residence rates have fallen dramatically [4]. This trend has gone hand in hand with the increased labor force participation and incomes of women. Government reform of survivor pensions and old-age benefits has also increased women’s old-age income [4]. While there has been an increase in multigenerational households as a result of the recent recession [5], demand for home assistance and nursing homes is likely to remain high in the coming years.

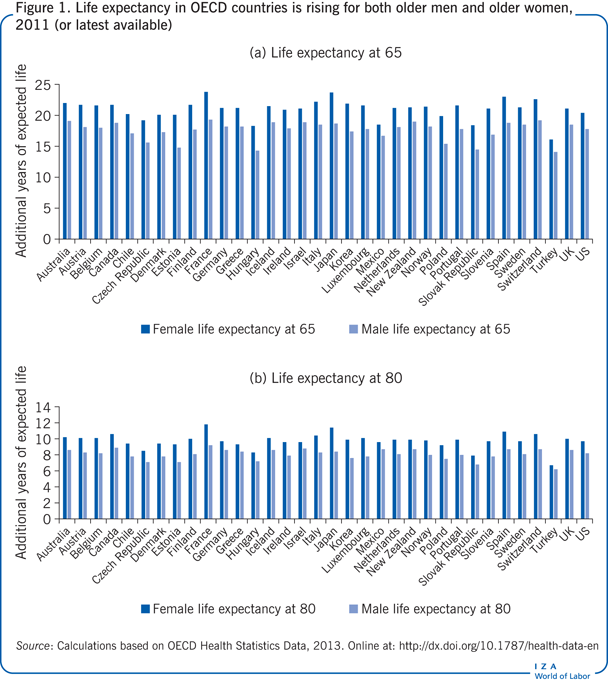

Projections of the number of elderly people who cannot perform the activities of daily living for themselves because of mental or physical impairments can be used to estimate how much increases in lifespan can be expected to raise demand for long-term care services. According to data from the Survey of Health Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE, a multidisciplinary survey covering more than 30,000 people aged 50 and over in many different countries) roughly 20% of people over the age of 65 are physically impaired [2]. Assuming a continuing rising trend in life expectancy, the rate of physical impairment may remain constant or fall slightly if health outcomes improve [6].

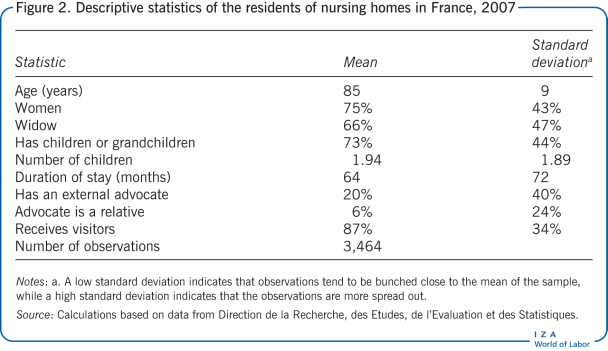

Despite the narrowing gender gap in life expectancy at older ages (Figure 1), most users of nursing homes are single (often widowed) women (Figure 2) [4]. This is partly due to better health outcomes for women than men and to the age difference between spouses. Although the age gap between spouses has fallen over time, husbands are still about two years older than their wives, on average, in most OECD countries, and more than 80% of older people live together as a couple. Women typically provide informal care for their husband until he dies, and then, when independent living is no longer an option, enter a nursing home.

Figure 2, drawn from a representative sample of residents at French nursing homes in 2007, indicates that the average age of residents was 85 years and that 75% of residents were women and 66% were widows. Moreover, 73% of the residents had children or grandchildren. The average number of children per resident was close to two (the count includes residents who had no children). About 87% of residents reported receiving visits from family and friends.

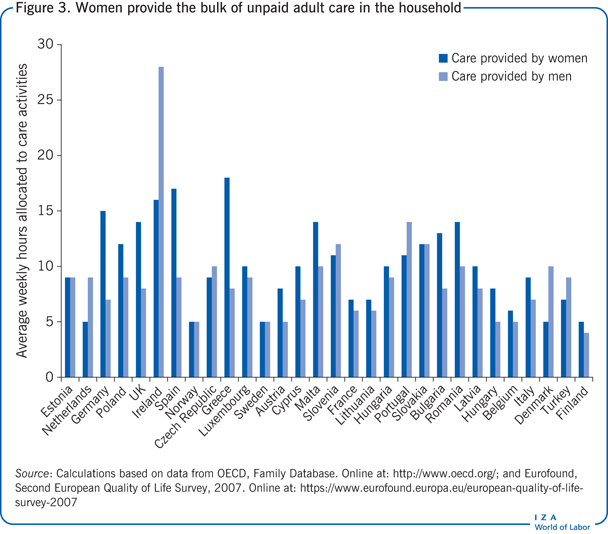

Informal care and institutional care: Complements or substitutes?

Generally, women provide the bulk of unpaid care in the household. The difference between men and women is smaller for adult care than for child care (Figure 3). Estimates of the time adult children spend caring for aging parents (in forgone employment and wages) are high [7]. While there is some substitution between informal care provided by family members and paid assistance at home, informal care is likely to be a limited substitute for nursing home care, as many nursing home residents require intensive medical care. Evidence from SHARE shows that informal care only weakly complements nursing home care [8].

Improving the quality of institutional care while reducing its costs

Studies of nursing home quality and regulation note that the long-term care industry faces three main problems: the high and rising cost of nursing home care, concerns about the quality of the care, and the inability of poor people to afford it [9], [10].

Demand for nursing home care is rising faster than the supply. The supply of nursing homes includes public, private, and non-profit institutions. And while most OECD countries have a national licensing system for nursing homes, the main constraint to expanding nursing home beds appears to be the limited supply of qualified nurses rather than undue regulation [1]. Excess demand also constrains the scope for cost reduction.

The main cost faced by nursing homes is the cost of employing qualified nurses [9], [10]. Increasing the supply of qualified nurses would enable expanding the supply of nursing homes while increasing competition between nursing home providers.

Standard ways of monitoring the quality of institutional care

Concerns about quality are another of the major problems with nursing home care. Reports of abuse of nursing home residents are not uncommon [2]. But measuring the quality of nursing home services is challenging. While advances in computerization and the development of standard clinical measures of user outcomes have made it easier to standardize quality measures, collecting such data entails extra costs for providers in required staff skills and hours of work.

To overcome the weak incentives to improve the quality of nursing home care and the failure of providers to self-regulate, many governments impose external regulatory controls, which usually focus on controlling inputs (labor, infrastructure) by setting minimum acceptable standards and enforcing compliance [1]. Quality monitoring is often decentralized to local authorities. The main instruments for regulating input quality are licensure, accreditation, and standard setting. Variations in accreditation and inspection practices and frequency are considerable across OECD countries. Audits and inspections commonly find safety violations, unsuitability of premises, inadequate staff and staff training, and lack of regular assessment of residents’ needs and autonomy. In some countries, public reporting of audits is mandatory. Some countries use standardized assessment results, including residents’ assessment instruments, and audits, inspections, and other administrative data. For a given institution, the maximum capacity and the required skill level of the staff are also often regulated.

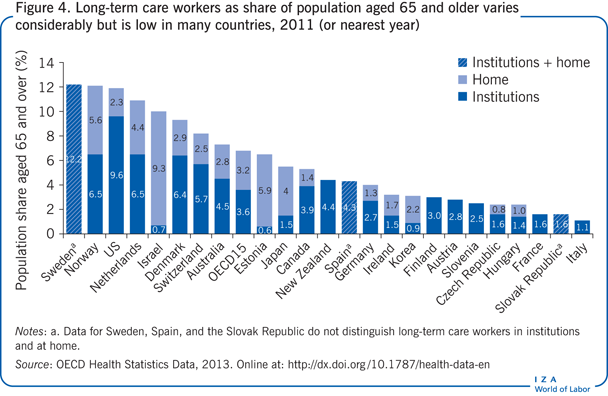

Regulating the quality of outcomes for institutional long-term care is much less common. The ratio of qualified nurses to residents is one of the most widely used indicators of the quality of institutional long-term care quality (Figure 4). This is obviously a limited indicator of residents’ well-being. More precise quality measures rely on assessments of the clinical condition of patients and typically focus on the prevalence of depression, falls and fall-related fractures, use of physical restraints, over-medication, and unplanned weight loss [1]. Dehydration is often a sign of mistreatment and neglect of residents.

However, regulations dealing with the clinical condition of residents may tempt nursing home providers to select only applicants in relatively good health in order to improve their clinical scores [11]. Excess demand makes this fairly easy to do. Another disadvantage of setting quality indicators based on clinical criteria is that providers may focus on meeting those criteria while neglecting other aspects of the services they provide. For example, nursing home providers may give less attention to illnesses that are not directly monitored or to recreational activities that are not part of the clinical criteria. Moreover, assessments are generally based on the average value of a series of clinical indicators rather than on each indicator individually. Thus providers may do very well on some indicators and very poorly on others and still receive an acceptable average score. And because nursing home residents do not always have their full cognitive capabilities, their subjective evaluations may not be reliable for monitoring the quality of services provided, though it is often argued that residents’ voice should receive more attention [12].

Alternative methods of monitoring quality

Thus the quality of nursing home services is difficult to monitor. The use of clinical reports for monitoring may induce providers to select only the healthiest applicants, while residents’ subjective reports may be compromised because of mental and physical impairments. However, many residents have regular visitors. These visiting family members and friends could be enlisted to provide regular evaluations of the services residents receive.

Preliminary evidence using data from a representative survey of the population of nursing home residents in France (author’s calculations prepared for this paper) indicate that a large majority of the residents (about 87% of the sample) receive visits from family and friends. Moreover, individual measures of subjective well-being correlate positively with receiving visits and having an external advocate. It must be acknowledged, however, that causation may run either way: it could be that instead of social networks leading to better health, better health increases residents’ chances of having external contacts. There is also evidence drawn from SHARE that informal care can complement weak nursing home care. One study finds that adult children provide on average five hours a month of informal care to elderly parents, with adult children in Italy and Spain providing about 12 hours a month and adult children in Sweden about three hours [8].

Feedback from visitors could be systematized. They could receive a short one-page questionnaire to fill out along with a pre-stamped envelope addressed to the authority in charge of evaluating the quality of long-term institutional care. Visitors could be asked to report on aspects of nursing home care that have been identified as indicators of quality, such as overall cleanliness, safety, restraints on the resident’s movement, improvement or deterioration in the resident’s health (including falls and fractures due to falls, any unintentional weight loss, signs of depression, dehydration, and sleeping problems, and any sign of under-treatment or over-medication). Related methods used to monitor long-term care services in some OECD countries include ombuds systems and adult guardianship [1]. The success of these practices suggests that family links could help in monitoring the quality of nursing homes.

Flexible or “portable” cash benefits have also been identified as a means of empowering the elderly and enabling them to affect the quality of the long-term care services they receive [2], [13]. People can choose how to spend their cash allowance, either for nursing home care or for assistance at home. Having the resources to make this choice could affect the quality of long-term care by enabling the elderly to switch from one nursing home to another or from one type of care to another in response to quality differences. Examples of cash benefits are the German Cash Allowance for Care, which is received by about one-fifth of elderly dependents in Germany, and the French Old-Age Benefit, which is universal but varies in amount with the recipient’s physical and financial resources. Some countries, such as Sweden, provide monetary allowances to family members for providing informal care to the dependent aged.

The main drawback with portable cash benefits is that they can easily be appropriated by family members and used for other purposes than intended. New forms of portable benefits that are flexible enough to allow the dependent elderly to use them to direct their own care but that are not necessarily in the form of cash may be needed to avoid these shortcomings.

Finally, modern nursing home designs that provide semi-independent living facilities resembling individual homes for each resident have also been introduced in some countries. These are proposed as a means to improve the living standards and well-being of long-term residents, preserving their right to privacy and to a life of their own [12]. Such projects have received considerable attention in the Netherlands, where the buurtzorg (neighborhood care) model has been very successful in providing home care that relies on nurses working directly with the elderly, their families, and the local community. This Dutch model entrusts nurses with considerable autonomy and responsibility, thus reducing some of the administrative time and cost burden of care. The same principles could be applied to new nursing home complexes in which residents have a home of their own and nurses work together with the residents and the medical staff, such as the non-profit Green House Project in the US. The Dutch buurtzorg model could be extended to a nursing home setting. It might also be possible in some cases to substitute qualified care workers for nurses, to relieve shortages of qualified nurses and lower the cost of this new type of nursing home arrangement.

Impediments to new methods of quality improvements

Family members may be reluctant to report honestly on the quality of long-term care if they feel that there are no feasible alternatives for their dependent elderly or if they believe that the quality of long-term care cannot be improved without incurring higher costs. This makes it all the more important to increase the supply of qualified nurses, so that supply shortages can be alleviated, giving the elderly and their families more options for long-term care providers.

Portable benefits that enable the elderly to select among different providers of long-term care services might have little impact on the standard of services provided as long as there is excess demand for these services. Moreover, fully flexible cash allowances may be appropriated by relatives, especially under conditions of a shortage of qualified workers. Placing too many restrictions on the use of the cash allowance to avoid such abuses is likely also to reduce their beneficial effects by making it difficult for the elderly and their families to use the benefits to select the best care option available. Therefore, new forms of non-cash, portable, and flexible long-term care benefits may be needed.

Limitations and gaps

Because the focus of this paper is institutional long-term care, it is not an exhaustive review of the literature on long-term care for the elderly. It does not examine the determinants of long-term care choices or the scope for substitution between long-term home care and long-term nursing home care. The choice of type of care depends in part on the medical condition of the dependent elderly person, and independent living is often correlated with better health outcomes [12]. Home care services are thought to be less expensive, which may be partly due to the more intensive assistance and costly medical care often required by nursing home residents.

Improving and monitoring the quality of nursing homes appears to be more pressing than measuring home care quality or informal care provided by relatives, because more severe abuses are reported for nursing home residents than for other forms of long-term care [2]. Whether this is due to selection into nursing homes of the most dependent elderly, with greater physical and mental challenges, is hard to determine because of the limited evidence available. Most surveys do not focus on the elderly and those that do consider only a single category, either nursing homes or home care. The evidence to date on the effectiveness of portable benefits and systems of guardianship to improve the quality of nursing home care is also scant. More evaluation studies are needed in this area.

Finally, there may be large differences in the quality of public, private, and non-profit providers of nursing home services. Although there is evidence for the US that demand for nursing home services is inelastic with respect to changes in the public health insurance system for the indigent elderly (Medicaid), it has been found that under conditions of excess demand, a 1% increase in quality would crowd out 3.2% of Medicaid patients in nursing homes.

Summary and policy advice

Monitoring and improving the quality of institutional long-term care is challenging. Nevertheless, from the studies discussed here it is possible to draw some tentative policy recommendations to improve the monitoring and quality of long-term care at little extra cost.

Portable old-age benefits, introduced by some OECD countries, empower the elderly to direct more of their own long-term care and may also improve the quality of long-term care services. These portable allowances should be fully flexible and should not be paid in cash, to avoid expropriation by others.

Many residents of long-term care institutions receive regular visits from family and friends. These visitors could be encouraged to help monitor the services provided by these institutions by reporting on their experiences in surveys. The ombuds systems and adult guardianship programs that some countries have implemented to monitor long-term care should be fostered more widely.

Nursing home arrangements that provide residents with individual living accommodations may also improve the quality of services, though keeping costs low may be more challenging in this setting. The Dutch buurtzorg (neighborhood care) model that gives nurses more autonomy to work with the families and the local community to reduce administrative costs of home care might be extended to more complex nursing home settings in which residents live somewhat independently.

The main cost facing nursing homes is that of employing qualified nurses [9], [10]. Increasing the supply of qualified nurses would enable nursing homes to expand services, while also increasing competition among nursing home providers, which should improve quality. During the current period of high unemployment in many OECD countries, it should be possible to increase the supply of nurses without having to pay higher wages by encouraging young men and women to take up nursing education [13]. To make the profession more attractive, career prospects should also be improved. In parallel, social workers could be qualified and trained to provide some care to the elderly, at lower cost than nurses.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author gratefully acknowledges financial support from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program for Research, Technological Development, and Demonstration under grant agreement 613247.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Elena Stancanelli