Elevator pitch

Many countries are experiencing increasing inflows of immigrant students. This raises concerns that having a large share of students for whom the host country language is not their first language may have detrimental effects on the educational outcomes of native children. However, the evidence is mixed, with some studies finding negative effects, and others finding no effects. Whether higher concentrations of immigrant students have an effect on native students differs across countries according to factors such as organization of the school system and the type of immigrants.

Key findings

Pros

In some countries, test scores of native children are not affected by the presence of immigrant children in the same classroom.

Increased immigration to the US has a small but positive net effect on the high school completion rate of native children.

Immigrant children who have stayed a few years or non-refugee immigrants may have no detrimental effects on their native peers.

If the share of immigrant children in schools is below a certain threshold, it may not affect native children.

Cons

In most countries, a high share of immigrant children in schools leads to lower test scores of native children.

A high share of immigrant students can lead to higher dropout rates from high school and lower chances of passing exams.

Native flight from schools that have many immigrant children can amplify negative effects on native children, as native parents move their children to schools with fewer immigrant children.

Native children with low parental education are most affected by immigrants in the classroom.

Author's main message

Recent evidence suggests that the effects of a high concentration of immigrant children on the educational outcomes of native children vary from negative to zero, depending on the country. Policymakers need to carefully consider any available evidence for their own country before implementing educational or immigration policies to address this problem. However, in most cases, the negative effects are rather small and seem to be related to disadvantaged immigrants or refugees. Thus, the effects might be remedied by improving immigrant children's language acquisition and providing general support to all children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Motivation

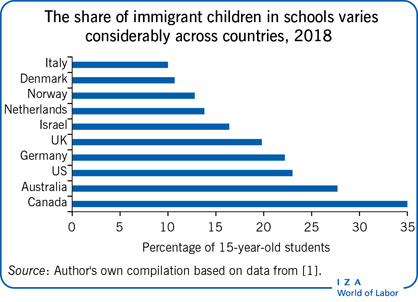

In recent decades, immigration has increased in many countries, most recently in the form of refugees. One result has been a rise in the share of immigrant children in schools. Many of these children do not speak the language of the host country as their first language; they are often of different religion and ethnicity than native children; and their parents are relatively poorly educated. This has raised concerns among politicians and parents that sending native children to schools with a high share of immigrant children may harm the educational performance of native children.

This concern has led to increased interest in whether there are educational spillover effects on the educational achievement of native children from having immigrant children in the same classroom or school. The question is whether native children are influenced by the ethnic composition in schools or classrooms, and if so whether they suffer or gain from being in a school or classroom with a higher share of immigrant children.

Besides such direct effects, there may also be indirect effects of immigration on the educational achievement of native children, for example, because of changed labor market incentives for educational attainment.

Discussion of pros and cons

Possible mechanisms behind spillover effects

Why do parents of native children fear that a high share of immigrant children in the classroom will reduce the quality of education for their children? There are several ways that could happen.

One of the most direct consequences of having many immigrant children in the classroom might be that the teacher's attention and time are diverted from the native children [2]. Since immigrant children typically have a poorer command of the host country language, the teacher may need to spend more class time providing individual assistance. The teacher may also slow the pace of instruction to accommodate immigrant children with limited language proficiency or a weak educational background. As a result, the teacher may cover less of the curriculum than the class would otherwise have covered. It is also possible that the teacher may adopt less language-intensive pedagogical methods, which could harm the learning experience of the native children in the same classroom.

Similarly, using a larger share of a school system's resources to support the needs of immigrant children could lower the quality of the education for the native children. However, in some school systems, classrooms or schools with a high share of immigrant children may qualify for additional resources, whether more money, more teacher time, or lower class sizes. These additional resources could counteract a negative spillover effect from having many immigrant children in the school or classroom.

As a slightly less direct consequence, teachers may lower their expectations for all students in classes with many immigrant students from disadvantaged educational backgrounds or with limited language proficiency. Thus, classes with a high share of immigrant children may cover less advanced academic content, thereby adversely affecting the native children.

In general, peer effects are believed to be important to education. Education experts argue that simply being around children from families with lower socio-economic and educational backgrounds may have a negative peer effect. If immigrant children coming from a disadvantaged background are struggling to perform academically, this peer effect may lead to worse academic achievements of native children. However, the opposite effect is also possible. If immigrant children come from more advantaged backgrounds than native children (in the case of positive selection of immigrants), immigrant children may have other characteristics that compensate for their lack of language fluency and thereby create positive spillover effects. Thus, the potential spillover effects may depend on the educational level and aspirations of the parents of the immigrant children in the school.

It might also be that ethnic and cultural diversity create a learning environment that is positive for learning outcomes. In this way, having immigrant children in the classroom or school could serve as a channel for transferring positive impacts to native peers.

Effects of immigrant concentration on native children's test scores

Recent studies have investigated the central question of whether a high share of immigrant children in the classroom or school affects the academic performance of native children. Academic performance is typically measured by test scores on major international assessments, such as the OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), or on national assessments. The tests typically assess knowledge of language, mathematics, and science, and the results are analyzed either jointly or separately.

A major problem in analyzing potential spillover effects is that children are usually not randomly assigned to schools. If schools with a high share of immigrant children tend to enroll a weaker group of native children (in terms of lower socio-economic and educational background) than schools with a low share of immigrant children, this may lead to the erroneous conclusion that the presence of immigrant children has negative spillover effects on native children. This problem commonly occurs in the case of immigrant children, since immigrants often live in ethnically concentrated low-income neighborhoods or in other low-income neighborhoods. Such residential segregation is likely to lead to segregated schools, which may seriously bias naïve estimates of the impact of immigrant concentration on native children's performance.

The problem is often reinforced by the so-called “native flight” from schools with a high share of immigrant children if, in response to a high concentration of immigrant children, native parents move their children to other schools, in particular to private schools. Thus, estimates of negative impacts of immigrant concentration on native children may simply reflect selective school enrollment of both immigrant and native children.

This selectivity problem has been solved in various ways. Some studies control for school-specific characteristics, or employ variation within schools to estimate the causal effects of immigrant concentration on native children's test scores [3], [4], [5], [6], [7] (or variation within siblings [8]). Other studies take account of the residential selection of immigrants by introducing an additional variable explaining (at least part of) the residential selection [9]. And some studies use specific events that increase immigration and the presence of immigrant children in a school as quasi-experimental evidence to find causal effects. That is the case for a study on Israel that exploits mass immigration from the former Soviet Union during the 1990s, and a study on England that exploits the eastern enlargement of the EU in 2005 [3], [10].

In most countries, the raw data show a negative correlation between the share of immigrant children in schools and student performance. However, this negative correlation may be a result of the selection problem discussed above. When appropriate account is taken of the residential selection of immigrants and the resulting endogenous selection into schools, the effect either stays negative or goes away, depending on which country is analyzed.

Two studies, on the Netherlands and England, find that the share of immigrant children has no significant effect on the academic performance of native children [3], [4]. Thus, the negative correlation in the raw data for these two countries can be explained by the selection or sorting of immigrant children into schools with less desirable characteristics, rather than by the share of immigrant children per se. Both of these studies look at primary school children (around 10 or 11 years old). In contrast, studies on Italy and Germany that also look at primary school children find negative effects of the share of immigrant children in the classroom on the test scores of native children [6], [7].

A study on Denmark uses PISA data on 15-year-old children to investigate the effect of immigrant concentration in schools on test scores of native children [9]. After controlling for the potential selection of immigrant families to certain residential areas (using immigrant concentration in larger geographic areas as an additional variable to explain the residential selection), it finds that a high concentration of immigrant children in school negatively affects test scores of native Danish children. The negative effect is stronger for mathematics scores than for reading scores.

Another study also uses PISA data and provides cross-country evidence for 19 countries [11]. One obvious challenge in using cross-country evidence is that more developed countries have more efficient school systems and attract more immigrants due to better economic opportunities. Therefore, simple cross-country data with countries at different levels of development in the sample tend to reveal a positive correlation between the average test scores of native children and the share of immigrants, but the correlation is spurious because of cross-country differences in economic development. To avoid these problems, the study aggregates PISA data at the country level and exploits the within-country variation over time in the share of immigrant children in school. It finds that a higher share of immigrant children reduces the test scores of native children, but the effect is small. The results are based on a small, non-representative sample of 19 countries and no generalizations to a broader set of countries are possible.

PISA data for different countries have also been used to examine whether the effects of immigrant children on their native peers are the same in different national school systems [12]. The focus has been on comparing non-comprehensive (ability-differentiated) school systems (represented by Germany and Austria in the analysis) with comprehensive school systems (represented by Denmark, Norway, and Sweden). The results suggest that the influence of immigrant children on native children's school performance is stronger in non-comprehensive school systems than in comprehensive school systems.

All the studies mentioned here estimate the total policy effect, which also includes all the indirect consequences of an increase in the share of immigrant children in the classroom or the school. In particular, this overall effect includes any adjustments made in class size in response to a high share of immigrant children (e.g. principals’ reactions to changes in class composition). If such changes in class size offset (fully or partly) the consequences of the higher share of immigrant children on native children, the total policy effect will be lower than the pure composition effect (defined as the effect of increasing the number of immigrants in a classroom, holding class size constant). A study on Italy exploits specific rules of class formation to identify this pure composition effect and finds that adding an additional immigrant child to a class while taking away a native child significantly reduces test scores of native students [6]. This pure composition effect is (as expected) stronger than the total policy effect, thereby confirming that a higher share of immigrant children in the classroom has a negative effect on the performance of native children.

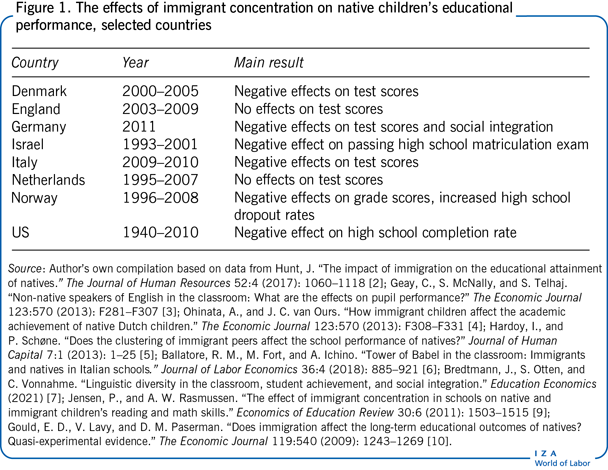

Effects on high school completion and exams

The previous section summarized studies focusing on the potential effects on test scores, including studies using PISA data gathered in secondary schools. This section adds to this evidence by summarizing some studies that look instead at effects on high school completion rates and exams (the main results are summarized in Figure 1).

A study on Israel uses the mass immigration from the former Soviet Union in the early 1990s to investigate the effects on native Israeli students [10]. This study provides evidence on the long-term effects of immigrants on native students, since it evaluates the effect of an increase in the share of immigrant children in the fifth grade on the high school matriculation exam pass rate, which is required to attend college. After controlling for the potential selection bias from the self-selection of immigrants to particular disadvantaged regions of Israel, the study finds that an increased share of immigrant students in the classroom has a negative effect on the probability of passing the high school matriculation exam.

A similar result is found for Norway, where an increased concentration of immigrant students in high school leads to a higher dropout rate for native students [5]. Again, the effect is still significant after controlling for potential selectivity problems. There is also some weaker evidence of a negative effect of the share of immigrant students on the grade scores of native students. The results also suggest that the quality of the immigrant students might be an important mechanism behind the observed effects. Investigations show that it is only immigrant students with low-skilled parents and immigrant students who arrived in Norway after school-starting age who have this negative effect on native students. This result may be interpreted as showing that it is the skill deficit of immigrant students that matters, not their ethnic background per se. Furthermore, the results also show that the negative effect of immigrant students is found only in the case of an above-average share of immigrant students, suggesting that a tipping point exists.

In the US, there has been long-standing interest in understanding the effects of immigration on the educational attainment of native students at both the high school level and the college level. This line of research includes analyses of the effect on high school graduation and college enrollment of native students when more immigrant students attend high schools and colleges. In addition, the US research also often looks at indirect effects of immigration on the educational attainment of native students.

Recent evidence on the US shows that an increase in the share of immigrant students in high schools has a small negative effect on the high school completion rate of native students. However, this negative effect is counteracted by a positive effect through the labor market channel. The rise in wage inequality resulting from higher rates of immigration is likely to increase the return to completing high school, as well as the completion rates of native high school students, resulting in a small but positive net effect of increased immigration on the high school completion rate of native students [2].

Native flight from schools with many immigrant children

The problem of segregated schools is often exacerbated by the phenomenon of native flight. In response to a high share of immigrant children in a school, parents of native children may decide to move their children to a school with fewer immigrant children, which in many cases would be a private school. This behavior can be seen as a rational response if parents are convinced that schools with a high share of immigrant children will harm the educational performance of their children.

Several studies report evidence on native flight for such diverse countries as Denmark, the Netherlands, England, and the US [3], [4], [13], [14]. For Denmark, the results show that native Danes are more likely to opt out of a school when the immigrant concentration exceeds 35%, whereas concentrations below this level do not affect their behavior. For the Netherlands, parents of native Dutch children are reported to choose schools with limited numbers of immigrant children, and interviews with parents have revealed that avoiding schools with high shares of immigrant children was the most frequently cited reason for the choice of their children's schools.

Other aspects of a high concentration of immigrant students

It may be that the potential effects of a high concentration of immigrant children on educational achievement or performance is not the main concern of native parents. Other aspects of the school environment may be equally important to parents, such as the incidence of bullying and crime. One study on the Netherlands finds some evidence of such effects [4]. Native Dutch children tend to experience more incidents of bullying when there are more immigrant children in the classroom. Despite this finding, the study finds no strong evidence of negative spillover effects on the test scores of the native Dutch children.

Looking more closely at the study results

For all the studies discussed here, an obvious question concerns the degree of precision of the estimated effects. In those studies that find a non-zero effect, the statistical analysis finds that the empirical evidence is strong enough to conclude that the effects are different from zero with a high degree of certainty (statistical significance). Thus, the question about precision is most relevant for the studies that find no effect. Is this finding due to lack of precision, or is a precise zero-effect estimated? The studies on the Netherlands and England that find a zero effect on native children's test scores both estimated this effect with a high degree of precision [3], [4]. In particular, the precision is very high for the estimates in the study on England, reflecting that the analysis is done using a very large sample of children. Therefore, the results showing that the share of immigrant children in the Netherlands and England does not have an effect on the academic performance of native children cannot be attributed to lack of precision in the estimated effects. Instead the estimated effects credibly show that no effect exists in those two countries.

Another question to ask about the results is whether they hold only on average or whether they apply equally to all native children. Many earlier studies examine only the potential spillover effect of the share of immigrant children on the average native child. However, the effect may depend on whether the native children are from weak or strong educational backgrounds. Two recent studies, on the Netherlands and Norway, examine separate effects on native children with low and high parental education [8], [15]. They both find that the negative effects only apply to native children with low parental education, whereas native children with high parental education are largely unaffected. Hence, immigrants in the classroom predominantly affect the educational attainment of native children already at risk.

A closely related issue is whether all levels of immigrant concentration have similar effects on the performance of native children or whether the effects are non-linear. For Denmark and Norway, the evidence indicates that the negative effects are mainly found at higher shares of immigrant children. This result suggests that the concentration of immigrant children has to be above a certain threshold to have detrimental effects on the educational outcomes of native children.

Earlier studies typically treat immigrant children as a homogeneous group, but recent studies also provide evidence that the type of immigrants is important. One important distinction is between immigrant children who have arrived recently and immigrant children who have already stayed in the country for some years. A study on the Netherlands finds that only the former group has a negative effect on native children's test scores in language [15]. This may be explained by the recently arrived immigrant children's weak command of the local language, which could affect instruction to the entire classroom. The result indicates that the integration process plays an important role.

Another distinction that has become more relevant in recent years is between refugees and other immigrants. A study on Norway finds negative effects of refugee children on the mathematics test scores of native children in primary school, but finds no effect of other immigrant children [8]. Hence, the reasons for migration are important when analyzing the impact of immigrant children in the classroom.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that several of the studies also examine the impact of immigrant concentration not only on native children, but also on immigrant children. The results indicate that the effect of immigrant concentration is often stronger and more negative for immigrant children than it is for native children.

Limitations and gaps

Reliable evidence on the effect of immigrant students in the school or classroom on native children's educational performance and attainment exists only for selected countries. Since schooling systems are very different across countries, care should be taken in generalizing the results to a wider set of countries. Instead, evidence is needed for countries that lack it.

Much of the evidence is for children in primary school, but very little is known about pre-school children (kindergarten, pre-kindergarten, and early childcare). Investments in early childhood education have been shown to be very important for success later in life, and therefore further research is needed on the effect of immigrants at this level. In systems of universal childcare, it will be important to know more about the effects of the share of immigrant children on native children, in particular on such aspects as school readiness.

By now there is clear evidence that the type of immigrants is important. However, it would be highly relevant to have more evidence from countries where immigrant children tend to come from more privileged socio-economic and educational backgrounds than native children (as is the case in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, for example, because of their positive selection immigration policies). Having this information would help in the design of immigration policies.

Summary and policy advice

The empirical evidence on the effects of immigrant children on the performance of native children in the same school or classroom is mixed. For some countries (the Netherlands and England), reliable studies did not find any evidence of such effects on the test scores of native children. For several other countries (Denmark, Germany, Israel, Italy, and Norway), similar studies found that high shares of immigrant children in a school or classroom had negative effects on native children in terms of lower test scores, higher high school dropout rates, and lower probabilities of passing the high school matriculation exam. In the case of US high school graduation, the negative effects of more immigrant students in high schools are outweighed by the labor market incentives created by the increased immigration, leading to a small positive net effect on the high school completion rate of native students.

One conclusion that seems to hold across all the countries where the issue has been investigated is that increased shares of immigrant children in schools lead to native flight. Many parents of native children are apparently so concerned about the impact of a high share of immigrant students on the quality of the learning environment that they move their children to a school with fewer immigrant children, which in many cases is a private school. In countries where no negative effects on the achievement of native students are found, these concerns are unjustified.

It is not surprising that the results differ across countries, as it is highly unlikely that the effects of immigrant children in the classroom would be the same everywhere. Such effects will obviously depend on the organization of the education system as well as the characteristics of the immigrant population. Education systems are organized differently across countries, and different countries attract different categories of immigrants.

Policymakers need to carefully consider any available evidence for their own country, as it seems very difficult to transfer results across countries. Possible policies might be to redistribute immigrant children more evenly across classrooms, or to limit the share of immigrant children in a class. Italy has a policy limiting the share of immigrant children in a classroom to no more than 30%. However, any such threshold should be based on convincing empirical evidence, which does not seem to be the case in Italy [6].

Even though negative effects are found for many countries, these effects are typically so small that the costs of many policies to deal with them (such as reallocation of immigrant children to schools with no or very few immigrant children) may well be greater than the benefits. Before implementing such policies to address the problem, it is advisable to perform cost–benefit analyses.

Evidence from selected countries indicates that it is mainly disadvantaged immigrant children (as measured by parental education, for example) who have a negative effect on the educational performance and attainment of native children. Furthermore, other education research has shown that this type of peer effect is common for all children. Thus, education policies could mitigate the negative effects that immigrant children have on their native peers by providing support to children with a disadvantaged background, instead of focusing solely on immigrant children.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of the article updates the figures, adds new research on the role of the parental education of native students and the impacts of different types of immigrants, and includes new “Key references” [1], [7], [8], [15].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Peter Jensen