Elevator pitch

Migration policies need to consider how immigration affects investment behavior and productivity, and how these effects vary with the type of migration. College-educated immigrants may do more to stimulate foreign direct investment and research and development than low-skilled immigrants, and productivity effects would be expected to be highest for immigrants in scientific and engineering fields. By raising the demand for housing, immigration also spurs residential investment. However, residential investment is unlikely to expand enough to prevent housing costs from rising, which has important distributional implications.

Key findings

Pros

High-skilled immigration attracts foreign direct investment.

Immigrants can help multinational firms find investment opportunities abroad.

Increasing the share of high-skilled immigrants has sizable income effects that can be attributed to productivity gains.

Foreign-born scientists and engineers particularly contribute to innovation and productivity growth.

Cons

Immigration is less likely to promote productivity growth when immigrants are low-skilled.

Residential investment triggered by higher immigration is insufficient to prevent housing costs from rising.

Temporary migrants put most of their savings into remittances, which do not boost investment in the host country.

Attracting high-skilled immigrants may lead to net brain drain for developing countries even though migration possibilities can spur educational investments.

Author's main message

Immigration by high-skilled workers attracts foreign direct investment, helps firms find investment opportunities abroad, and raises per capita income by boosting productivity. However, despite triggering residential investment in the host country, immigration also raises housing costs, with undesirable distributional effects. Brain drain potentially also harms home countries. Policymakers should thus consider selective immigration policies that attract high-skilled workers, accompanied by redistributive measures that benefit low-income households in the host country and by compensating measures for the home countries that lose part of their high-skilled workforce.

Motivation

Modern economic growth theory suggests that the interaction of technological progress and capital accumulation is the ultimate source of long-term economic growth. Whether immigration flows cause changes in labor productivity through investments in capital and research and development (R&D) is an important issue for policymakers. Examining how immigration affects capital formation and productivity requires a dynamic perspective that includes the effects on the accumulation of residential and non-residential physical assets, intangible assets (knowledge capital), and human capital (skill formation). For instance, technological improvements could arise as a result of the immigration of high-skilled workers with science and engineering (S&E) skills. Moreover, immigrants may help foreign firms find investment opportunities in the host country and foster foreign direct investment (FDI).

It is important to distinguish potentially differential impacts of temporary and permanent immigration and diversity of migrants according to skill. The income distribution effects through the impact on housing costs also need to be considered. If immigration raises housing costs because the demand for housing expands faster than supply, welfare decreases, particularly for poorer households because of their higher expenditure share for housing. Social responsibility also requires consideration of the (brain drain) effects of immigration policies on home countries.

Discussion of pros and cons

The interaction between international migration and investment has been studied much less than, for example, the labor market effects of immigration on native-born populations and foreign-born workers already living in host countries. (Immigrants are typically defined as foreign-born individuals aged 25 or older.) Although the typically estimated shorter-term effects of immigration on employment and wages are small, migration may lead to larger increases in wage income in the longer term by enhancing FDI in both the home and the host countries as well as by boosting productivity in the host country.

Migration and physical capital investment

Measures of FDI flows capture international movements of physical (productive) capital rather than other financial assets. FDI is one potential channel through which migration could affect labor productivity in both home and host regions. That is because immigrants may reduce information frictions that typically lead to a bias against investing in business ventures in foreign countries, about which firms know much less than they do about their home country. Increasing FDI may not only raise the physical capital stock, but also improve technology and thus result in productivity gains.

Inward foreign direct investment

Under conditions of international or interregional capital mobility, labor market integration that leads to immigration of workers attracts capital inflows because of the complementarity between capital and labor in producing goods and services. Similarly, emigration slows capital formation.

It is important to distinguish the causal effect of migration on capital movements, which is clearly positive under capital–labor complementarity, from the correlation between them, which may be weak. In fact, labor and capital may move in opposite directions across countries and regions. For that reason, little correlation may be observed between capital accumulation and labor flows, even in the case where the causal effect from net migration on the change in the capital stock is unambiguously positive. A prime example is the opposite movement of labor and capital following the reunification of Germany in 1990. There have been substantial migration flows from East to West Germany, while capital accumulated faster in the East [5]. The pattern can be explained by neoclassical growth theory [6]. Consider a low-productivity region with a capital stock per capita that is below its long-term level. Integration of labor markets then leads to labor outflows (because of low wages) while at the same time capital will move into the region (because of a relatively high return on capital investment). Importantly, however, capital accumulation occurs at a slower rate than without emigration. By contrast, if labor market integration occurs when the regions involved are sufficiently developed, then labor and capital flow in the same direction.

The challenge for empirical research is to identify causal effects between immigration and FDI. One study looks at the two-way relationship of stocks of immigrants and stocks of inward FDI from foreign countries into the 16 German states over the period 1991–2002 [7]. It finds that inward FDI is significantly increased by a higher stock of immigrants, if it comes from high-income countries. One possible explanation for this effect is that immigrants assist in interactions with foreign companies in their home country, thus helping overcome information problems. Unlike a higher stock of immigrants, a larger domestic labor force does not promote inward FDI.

Outward foreign direct investment

A higher stock of immigrants also has a positive impact on the stock of international bank loans from the host country to the immigrants’ home country [8]. The effect is particularly large when the immigrants are high-skilled and the two countries do not share a common language, legal heritage, or colonial past. This suggests that immigrants are particularly important for facilitating cross-border financial flows when informational problems are severe.

Moreover, there may be a positive effect from immigration on outward FDI from the host country to the immigrants’ home country. For instance, a larger immigration stock of both low-skilled and high-skilled workers in the US in 1990 has been shown to have lead to higher subsequent growth of outward FDI financed by US firms over the period 1990–2000 [9]. The channels through which immigration affects outward FDI may differ for low-skilled and high-skilled migrants, however. One hypothesis is that investors in developed countries with little advance information about the quality of the labor force in developing countries observe a rather high productivity of immigrants despite their few formal qualifications, take it as a signal of the quality of the labor force in the home country of the immigrants, and thus are more positively inclined to invest there than they would be without that signal. High-skilled immigrants, by contrast, may actively contribute to the creation of international business networks, particularly through their language skills.

Demonstrating causality is usually achieved by constructing a measure of migration that is based on bilateral migration flows. These are determined by geographic and cultural distance between countries, or past migration; that is, by external factors that have no direct effect on investment or productivity gains. Using such an externally determined migration variable rather than actual migration avoids that the estimated migration effects actually come from omitted determinants of investment and productivity that are correlated with migration and would therefore bias estimation results. The most common approach to avoiding such omitted-variable bias is to use historically rooted migration stocks of different immigration groups for constructing the external migration measure. The approach is based on the notion that potential migrants choose their destination based on the number of prior migrants from their home country. The idea is that those migrants provide a social network based on family or cultural ties.

This method is used, for instance, in a study that accounts for the possibility that outward FDI induces migration of workers in foreign subsidiaries to the US headquarters of multinational companies (reverse causality) [10]. The study employs the total stock of migrants from a home country using the share of the stock of migrants in that country's population 30 years earlier. The results suggest that a 1% increase in the stock of college-educated immigrants in the US raises the stock of outward FDI from the US to the home country of the immigrants by about 0.5%. The effect is slightly lower for an increase in the stock of all immigrants.

Savings and remittance behavior of immigrants

It is also interesting to examine the savings behavior of migrants and whether they invest their savings in the host country or remit them to their family members who have not migrated. The literature suggests that both the savings rate and the amount of remittances depend on whether migrants are temporary or permanent. For example, immigrants in Germany seem to have lower saving rates, on average, than native-born residents with similar characteristics. Immigrants who plan to stay only temporarily, however, tend to save more and not less than natives; they remit more than immigrants who plan to stay permanently [11]. Thus, remittances are a major motive for savings, particularly for temporary migrants who plan to return home sometime in the future. Those savings are not invested in the host country but may help to accumulate productive capital in the home country. Particularly in home countries where credit markets for financing productive investments are underdeveloped, remittances may be able to boost school enrolment, reduce child labor, and promote entrepreneurship.

Migration and knowledge capital formation

Immigration may also be important for the accumulation of intangible assets. High-skilled immigrants with S&E skills contribute to technological improvements in the host countries. While it is common to use formal intellectual property, such as number of patents, to measure innovation, informal investments in tacit knowledge and organizational improvements by managers and other professionals can also lead to productivity gains. Thus, to gauge the impact of immigration on intangible assets through observable and unobservable R&D not only the number of patents should be looked at, but also total factor productivity (TFP) growth (output growth that is not explained by the amount of inputs used in production).

Immigration and patent activity

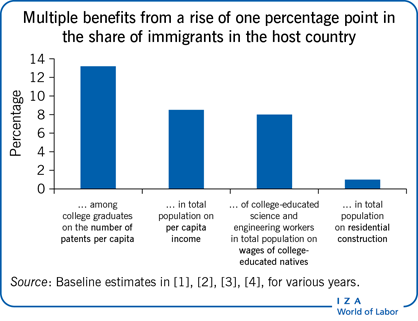

Survey evidence from US college graduates offers insights into the patenting behavior of immigrants and native-born residents [1]. It suggests that immigrants are one percentage point more likely (probability of 1.9%) than natives (0.9% probability) to be granted a patent. That difference can be attributed entirely to the fact that the share of immigrants with an S&E degree is higher than the share of the native-born population. Based on the estimation at the individual level, increasing the share of college-graduate immigrants in the population by one percentage point raises the number of patents per capita by 6%.

It has been argued that a country may nevertheless not gain from increased patenting through the immigration of scientists and engineers. Theoretically, immigrants’ patents could also crowd out the patenting activity of native-born workers. It is also possible that if the college graduates had not immigrated to the US, they would have applied for their patents elsewhere and the US might still have benefited from these patents through cross-country knowledge spillovers. However, the evidence does not support these theoretical possibilities that would challenge the hypothesis of positive effects of immigration on patenting. Using 1940–2000 US state data suggests positive knowledge spillovers within the US from a higher share of college-graduate immigrants on the patenting activity of the native-born population [1]. To address the possibility that this finding simply reflects that immigrants choose host countries with high patenting activity, the study looks at changes in patents over time. It also employs a measure of the share of immigrants in the workforce (ages 18–65) that is externally determined by using the stock of immigrants in 1940 (rather than the actual one) from various home countries. A one percentage point increase in the externally determined workforce share of immigrants with a college degree (3.5% in 2000) boosts patents per capita by 13.2% within ten years (as displayed in the Illustration). The effects of increases in the college-educated native population are much lower (in the range of 2–6%). Moreover, a one percentage point increase in the share of immigrant scientists and engineers in the workforce boosts the number of patents per capita by an astonishing 52%—more than twice as much as for a one percentage point increase in the share of scientists and engineers in the native-born population.

A study using Canadian data suggests that a higher university-educated immigrant share has particularly large patenting effects in the US because of its comparatively high share of those graduating from STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields and a high share of STEM graduates that are actually working in STEM-related jobs. Nevertheless, it is possible to conclude that immigration of college graduates has positive and considerable effects on innovation, particularly the immigration of scientists and engineers. The positive effects may not only come from a different composition of college graduates between migrants and non-migrants according to study fields but also from a positive ability selection of migrants for a given field of graduation. Moreover, there is evidence that migrants help economies to overcome skill shortages—resulting from structural change, demographic shifts, and other shocks—better than natives.

In contrast, immigration of low-skilled individuals, as a study on the inflow of ethnic Germans (so-called “Aussiedler,” who are descendants of Germans that emigrated in the 18th and 19th century) mainly from the former Soviet Union to Germany in the 1990s suggests, does not trigger any important effects on patenting activity.

Productivity effects of immigration

Other studies examine the overall productivity effects of immigration, not just through patenting. While there is mixed evidence on the adoption of labor-saving technology in response to low-skilled immigration, again, the US offers a good opportunity to examine the importance of foreign-born college-educated scientists and engineers. The US H-1B visas allow foreign workers to migrate temporarily to the US to work in “specialty” occupations such as those requiring S&E skills. One study estimates the wage effects of an increase in scientists and engineers attributable to changes in the number of H-1B visas issued in 219 US cities over 1990–2010 [2]. It finds that a one percentage point increase in the share of foreign-born scientists and engineers in the working population boosts average weekly wages of native-born college-educated workers by 8–11% (shown in the Illustration) and those of native-born non-college-educated workers by almost 4%. These results point to positive productivity effects of attracting scientists and engineers from abroad. As a caveat, the increase in the share of foreign-born scientists and engineers in the working population over the period of the study was just 0.53 percentage points (two-thirds of the total increase in the employment share of scientists and engineers in US cities). It is unclear, though, whether the large effects found in this study would hold with heavier inflows of foreign-born scientists and engineers, possibly of lower average quality.

Long-term effects could also come from attracting foreign-born PhD students to STEM fields. There is evidence that such students increase academic output (as measured by number of scientific articles). It is also possible that basic research activity as measured by scientific articles has positive productivity effects. On the one hand, these effects may take longer to arise than from immigration of scientists and engineers (rather than PhD students). On the other hand, PhD students graduating in the host country have better chances to signal their skills to potential employers.

To gauge the role of immigrants for productivity, researchers have also exploited international data on bilateral migration stocks across countries that includes information on migrants’ education level (e.g. on how many college-educated, working-age immigrants from Greece live in France) [3], [12]. Using the past emigration stock to construct an external measure of high-skilled migration into OECD countries, one study suggests a moderately positive effect on the ratio of TFP in the host country to TFP in the home country. For example, a five percentage point increase (a doubling) in the ratio of college-educated migrants from a migrant-sending country to the college-educated population living in an OECD host country raises relative TFP in the host country by one to two percentage points [12].

Another study estimates the effect of a larger (externally determined) immigration share on per capita income and productivity [3]. The results suggest that a one percentage point increase in the immigration share (which is, on average, 4% for the sample of 181 countries) raises per capita income by about 6–10% (referred to in the Illustration). The effect is driven almost entirely by the increase in TFP while the per capita stock of physical capital is basically unaffected. The productivity effect can be attributed to the contribution of immigrants to innovation activity and the diversity of productive skills. By contrast, more openness to trade (larger sum of exports and imports as a share of GDP) has no effect on per capita income once the migration share is accounted for. This comparison between migration effects and trade effects illuminates possible biases in studies that estimate the effects of trade expansion on per capita income when not controlling for the contribution of immigrants at the same time.

Immigration contributes to the diversity of the population in many ways, and it is important to distinguish different measures of diversity. While the literature has focused largely on the change in the composition of education levels in response to immigration, diversity can also refer to genetic or cultural diversity. The different forms of diversity may not be strongly correlated, and they may have different effects on economic prosperity in the host country. The literature suggests that the optimal degree of diversity balances the positive complementarities in production between immigrant and native-born workers that arise from the different skills associated with different cultural backgrounds and the increasing costs of communicating in culturally diverse work environments.

When cultural diversity leads to ethnic fragmentation, productivity effects of increased diversity may be predominately negative, especially in developing countries. Meanwhile, birthplace diversity (the probability that two individuals drawn randomly from the population were born in different countries) has predominantly positive effects [13]. The result points to skill complementarities between the immigrant and native-born population. A country's birthplace diversity is composed of the share of immigrants in the population and the birthplace diversity among those immigrants. Both variables are individually found to have a positive effect on per capita income. The effects are larger for skilled immigrants than for unskilled immigrants. Again, this confirms the expectation that positive productivity effects come from skilled immigrants. The positive effects are particularly strong for patent applications per capita and total factor productivity, two potential drivers of higher per capita income. The results still hold after controlling for measures of ethnic, linguistic, and genetic diversity.

Skill formation of migrants

Apart from accumulation of physical capital and intangible assets, the skill formation of migrants also potentially affects labor productivity in host countries. Like for savings, the anticipated length of a migrant's stay is critical for incentives to invest in destination-specific human capital, like language skills or some forms of vocational training [11].

A potential way to spur human capital accumulation of migrants is to facilitate access to citizenship. There is evidence that citizenship law reforms in Germany raised weekly earnings (a measure of labor productivity) and vocational education levels of immigrated men. Immigrated women benefited from more job stability and higher employment rates [14]. Reasons for beneficial effects of naturalization include better matches between workers and firms. For instance, naturalization implies that job restrictions attached to nationality are lifted. Moreover, incentives for firms to integrate naturalized workers are higher, presumably because they signal a longer-term commitment to stay in the host country.

Migration and economic development: Brain drain or brain gain?

But what about brain drain and the ethics of depriving other countries of their most productive workers? For migration between developed countries, the effects appear to be moderate. The free movement of labor within the EU may aggravate income differences across member countries to some degree, while at the same time generating efficiency gains by letting workers move to the location where they are most productive [12]. Equity concerns call for redistributing the efficiency gains in the host countries through compensating public transfers across EU member states.

Immigration from developing to developed countries may have unexpected effects in the home countries that mitigate losses from emigration of skilled workers. There is evidence that lowering immigration barriers in order to increase the likelihood that skilled workers will be able to emigrate from poor countries with low levels of human capital could stimulate human capital investment in home countries. This could, in turn, result in a net brain gain rather than a drain. However, the effects differ across countries, and more countries are found to lose than gain. Thus, skill-selective immigration policies, while most effective in terms of enabling productivity increases in host countries, are often at odds with development goals for some poorer countries.

If skill selection of migrants is preferred over broader liberalization of migration policies that includes non-economic reasons for migration, developed country policymakers should consider possible ways of compensating developing countries. Options include offering study visas for potential immigrant students and fostering technology transfers.

Migration and residential investment

Numerous studies suggest that immigration also affects housing costs. At the local level, housing rents may not significantly rise if immigrants with comparatively low income move into a neighborhood and drive out higher-income earners, who relocate to richer neighborhoods. Out-migration at the local level, however, raises housing costs in other neighborhoods. Thus, at a less disaggregated level, immigration unambiguously leads to higher housing costs through an increase in overall demand for housing services. Immigration effects on housing costs are found to be lower in countries with less welcoming attitudes toward immigrants and higher when immigrants are wealthier.

Higher demand for housing also leads to higher investment in residential housing. The important question is whether the supply response is large enough to offset the price increases from rising demand that are triggered by immigration, at least in the longer term. The effect of immigration on housing supply through investment in residential construction is not nearly as well studied as its effect on housing rents and house prices. One exception is an investigation of the effect of regional immigration on residential construction in Spain [4]. By using past immigration to construct an external measure of current immigration at the regional level, the study accounts for the possibility that immigrants locate into economically booming regions. As Spain's total population grew by 1.5% a year over 2001–2010, with an average annual increase in the immigrant share in the population of about 1.3 percentage points, the number of new housing units grew 1.2−1.5% a year. In other words, a one percentage point increase in the immigrant share in the population led to a roughly 1% increase in residential construction (see the Illustration). Half the residential construction boom in Spain can thus be attributed to immigration.

Despite the increase in residential construction, however, housing costs increased by about 2% per year. The explanation for this is rooted in the scarcity of residential land. The combined effect of higher demand for housing and higher supply of housing associated with higher population density raises land prices. The land area available for residential construction can be extended only within naturally determined limits. Consequently, land prices are likely to grow in line with housing demand [6]. Ultimately, despite its effect on residential construction, immigration thus leads to higher rental rates for housing. This has first-order distributional effects because the housing expenditure share is decreasing in wealth and income. Welfare is thus declining particularly for poorer households.

Limitations and gaps

Though consistent, the evidence that immigration is positively related to capital investment, productivity, and innovation is still rather limited and largely confined to the US. More evidence at the regional level within other countries is also needed on the effects of immigration on FDI and residential construction.

No empirical studies have been conducted so far on the two-way interaction between immigration and residential investment. Intuitively, while immigration triggers housing demand and residential investment, inadequate residential investment because of zoning restrictions can lead to high housing costs that discourage immigration. The wage gains of immigrants in the host country compared with the home country could be nullified by rising housing costs in the host country, thereby further discouraging immigration. It would thus be interesting to know more about the interaction of immigration and zoning regulations for residential construction.

The evidence strongly suggests that high-skilled immigrants stimulate capital investment and raise productivity in the host country, but much less is known about the potential effects of migration, particularly of low-skilled migrants, on capital formation in home countries. A potential avenue for such impacts is through remittances, which could support entrepreneurship among migrants’ family members who remain behind in the home country.

Summary and policy advice

Empirical evidence suggests that immigration of educated workers attracts FDI, helps firms find investment opportunities abroad, and raises per capita income by enhancing labor productivity. Particularly the immigration of scientists and engineers stimulates innovation in the host country through patenting. The migration of low-skilled workers seems to have less impact on capital formation in host countries. The evidence supports the design of selective immigration policies to attract high-skilled workers, particularly those with STEM skills. Greater birthplace diversity in a population through immigration is also found to foster economic prosperity, particularly if immigrants are well-educated.

However, there is the issue of potential brain drain in developing countries that lose part of their skilled workforce in response to skill-selective immigration policies in host countries. Such emigration may conflict with development goals and may lead to a net skill loss in home countries, despite potentially positive effects on educational investment associated with migration prospects. Admitting more students from developing countries on student visas in developed countries is one way to compensate for brain drain.

From a development policy perspective, the main benefit of emigration for the home country comes from remittances. Because remittances tend to be higher from temporary migrants than from permanent migrants, providing opportunities for temporary work in developed countries may be conducive to economic development in home countries. However, temporary migrants have less incentive to learn the host country language, which is an obstacle for improving their earnings prospects over time.

Despite the many potentially positive effects of immigration, policymakers have to be aware that high levels of immigration can provoke a backlash against liberal immigration policies in host countries, especially if housing costs rise as a consequence. Not everyone in the host country may benefit from immigration despite welfare gains in the aggregate. Possible measures to redress the imbalance include transfers to low-income households (who typically rent rather than own housing property and have comparatively high housing expenditure shares), possibly financed by increases in taxation of housing property, financial wealth, and bequests. In other words, undesirable distributional effects associated with higher housing prices could be addressed by the tax-transfer system instead of limiting immigration and forgoing welfare gains from immigration.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Aderonke Osikominu, anonymous referees, and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author (together with various co-authors) contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in major parts of this article [6], [12], and Felbermayr, G., V. Grossmann, and W. Kohler. “Migration, international trade and capital formation: Cause or effect?” In: Chiswick, B. R., and P. W. Miller (eds). The Handbook on the Economics of International Migration, Vol. 1B. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2015. Version 2 of the article includes further evidence of the effects of immigration on knowledge capital formation, includes a section on the skill formation of migrants, and adds new “Key references” [8], [14].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The author declares to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Volker Grossmann