Elevator pitch

The relationship between female labor force participation and economic development is far more complex than often portrayed in both the academic literature and policy debates. Due to various economic and social factors, such as the pattern of growth, education attainment, and social norms, trends in female labor force participation do not conform consistently with the notion of a U-shaped relationship with gross domestic produc (GDP). Despite the initial impact, Covid-19 did not have a lasting negative effect, on average, on women’s participation. At the same time, some countries have made significant progress in increasing participation rates for women, including those who have started from a lower level.

Key findings

Pros

Female labor force participation is an important driver (and outcome) of growth and development.

The participation of women in the labor force is impacted by various economic and social factors, ranging from positive pull factors, including educational attainment, and more challenging push factors, such as poverty.

Covid-19 did not leave a lasting impact on women in most labor markets and, encouragingly, a number of countries have made progress in increasing women’s participation in recent years.

Increased access to quality education (beyond secondary), social protection and care services support better employment outcomes for women.

Cons

Even when gender disparities in participation rates are low, women tend to earn less than men and are more likely to be engaged in unprotected jobs, such as domestic work.

Education raises the reservation wage and expectations of women, but it needs to be matched by the creation of the necessary jobs.

Underreporting is common, so data on women’s participation rates do not accurately reflect women’s work.

Author's main message

The relationship between women’s participation in the labor force and development is complex and reflects changes in the pattern of economic growth, educational attainment, fertility rates, social norms, and other factors. However, labor force participation rates paint only a partial picture of women’s work. More important is understanding the quality of women’s employment, wages, and the ability to get positions of leadership. To achieve gains in job quality in developing countries, policies should focus on both labor demand and supply dimensions. Expanding access to secondary and higher education is particularly relevant but this needs to be matched by the creation of jobs that can be accessed by women.

Motivation

Women’s participation in the labor market varies greatly across countries, reflecting differences in economic growth, social norms, education levels, fertility rates, and access to childcare and other supportive services. The relationship between female labor force participation and these factors is complex. One dimension that has been widely examined is the U-shaped relationship between economic development and women’s labor force participation, most notably by Claudia Goldin, winner of the 2023 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences [1].

Focusing on these issues is critical because female labor force participation is key to promoting inclusive growth and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 5 (“Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”). Beyond the absolute numbers, the far more important concern is the nature of jobs that women are able to engage in.

This article highlights the complex nature of female labor force participation in developing countries and presents findings on the key trends and factors that drive women’s engagement in the labor market and access to employment. It examines specific insights from different regions, while exploring the impact of Covid-19 and post-pandemic trends. Above all, the article stresses the importance of looking at the quality of employment and means to promote better outcomes for women in the labor market.

Discussion of pros and cons

Development has involved two related transitions: the movement of workers from agriculture to manufacturing and services and the migration of people from rural to urban areas. These transitions were associated with rising levels of education, declining fertility rates, and shifts in other socio-economic drivers of labor force participation, with specific gender implications for the labor market.

In this context, female labor supply is both a driver and an outcome of development. As more women enter the labor force, economies have the potential to grow faster in response to higher labor inputs. Women’s supply of labor increases household incomes, which helps families escape poverty and increase their consumption of goods and services. At the same time, as countries develop, women’s capabilities typically improve, while social constraints weaken, enabling women to engage in work outside the home.

However, labor force participation is the outcome of not only supply-side factors, but also of the demand for labor. In particular, the nature and spatial distribution of economic growth and job creation help determine whether women can access jobs, particularly in a context where social norms dictate how and where women can work. As seen in developing countries that have experienced rising female labor force participation, labor intensive manufacturing has traditionally provided an important conduit for women to work outside the home, albeit often in difficult working conditions [2].

The relationship between evolving socio-economic and demographic factors and how women participate in the world of work is multifaceted. In particular, whether a woman is working may be driven, on the one hand, by poverty (as evident in low-income countries) and, on the other, by women’s increasing educational attainment and the opportunities to work that are made available in a more modern economy. Moreover, during periods of crisis and in response to economic shocks, women are often required to take up (typically informal) employment to smooth household consumption. This occurred in Indonesia in the wake of the East Asian financial crisis of 1997–1998 [3].

Beyond analyzing labor force participation, it is critical to look at the nature of women’s employment. In general, when women work, they tend to be paid less and to be employed in low-productivity jobs.

Global and regional trends in female labor participation are diverse

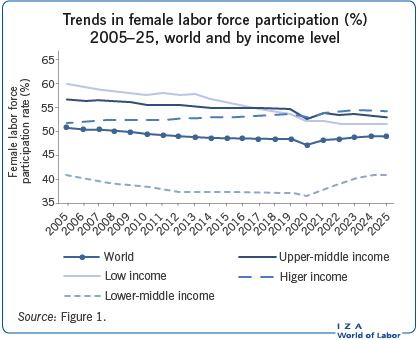

Over the last two decades, the global female labor force participation rate (age group 15+) has declined, despite upward trajectories in some regions, from 50.7% in 2005 to 48.8% in 2025 (ILO modelled estimates, http://www.ilo.org/ilostat). Though almost 320 million women have joined the labor market in the past 20 years, women still account for just 40.2% of the global labor force, a figure that has not changed much over this period.

As education enrollment rates have risen across the world, labor force participation rates have fallen among school-age youth (a positive trend for both young men and women). Thus, despite falling female labor force participation rates, the gender gap has narrowed slightly, from 26.4 percentage points in 2005 to 24.1 percentage points in 2025 (ILO modelled estimates, age group 15+).

Despite the significant impact of the Covid-19 lockdowns on women’s employment (especially among young women) in 2020 [4], the global female labor force participation rate bounced back over 2022-24 to a level witnessed back more than a decade ago and around a percentage point above the level predicted by the pre-Covid-19 (downward) trend.

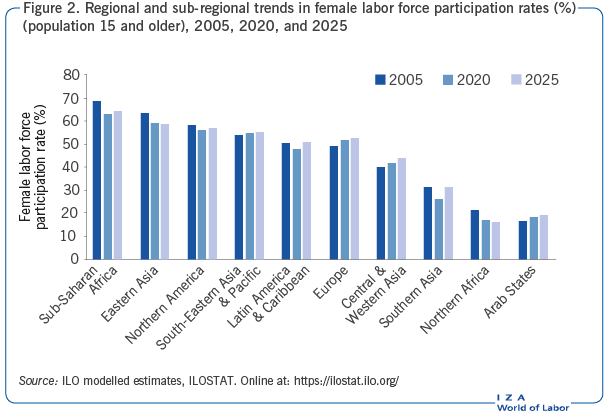

At a regional level, there is considerable diversity in the overall levels and trends over the last two decades, including during and following Covid-19. The female labor participation rates have been highest in sub-Saharan Africa and Eastern Asia and lowest in Southern Asia, Northern Africa, and the Arab States. Latin America and the Caribbean and Southern Asia experienced a decline in 2020 during the Covid-19 lockdowns followed by a stronger recovery post-pandemic. During the same periods, participation rates increased in South-Eastern Asia and the Pacific, Northern, Southern, and Western Europe, Central and Western Asia, and the Arab States. Northern Africa is the only (sub)region to experience a decline.

Several countries have made significant gains over recent years in increasing the participation of women in the labor force, often supported by explicit policy measures to achieve this goal. The push for increased participation has resulted in some progress in countries with a low initial starting point, including Qatar and Saudi Arabia, which have witnessed an increase by well over 10 percentage points during the last decade. Other countries to experience a significant rise in female labor force participation rates in recent decades,from various starting levels, include Malta, India, Bangladesh, Japan, Turkey, Singapore, and Chile.

Empirical evidence: Factors and determinants

Given the complex nature of female labor force participation in developing countries, it is important to analyze how socio-economic factors affect the decision and ability of women to engage in the labor market. The key, often overlapping, dimensions considered in the literature include [5], [6]: level of economic development and the nature of growth; educational attainment; household income; social dimensions, such as social norms influencing marriage, fertility, and women’s role in and outside of the household; and institutional setting (laws, protection, benefits).

Is the U-shaped relationship between development and female labor force participation more than a stylized fact?

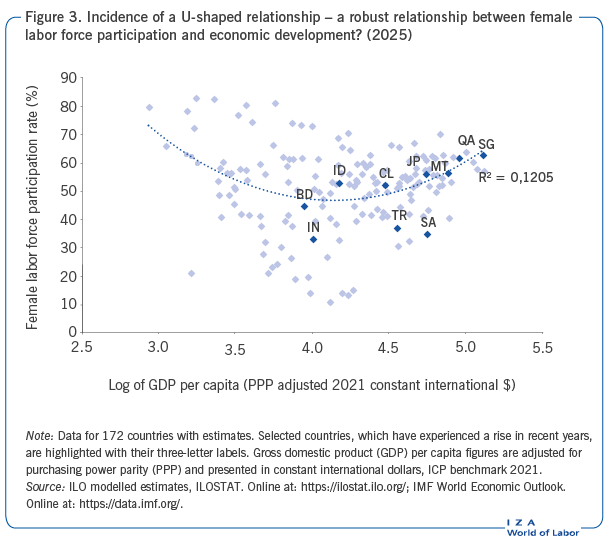

A much-discussed hypothesis in the literature, explored in a large number of studies, proposes that there is a U-shaped relationship between economic development and women’s participation in the labor force [1]. The stylized argument is that when a country is poor, women work out of necessity, mainly in subsistence agriculture or home-based production. As a country develops, economic activity shifts from agriculture to industry, which benefits men more than woman. At higher stages of economic development, education levels rise, fertility rates fall, and social stigmas weaken, enabling women to take advantage of new jobs emerging in the service sector that are more family-friendly and accessible. At a household level, these structural shifts can be described in the context of the neoclassical labor supply model: as a spouse’s wage rises, there is a negative income effect on the supply of women’s labor. Once wages for women start to increase, however, the substitution effect will induce them to increase their labor supply.

Data for a large set of 172 countries for 2025 show (weak) evidence of a U-shaped relationship between the log of GDP per capita (adjusted to serve as a proxy for economic development) and the female labor force participation rate (Figure 3). Some countries, including Qatar, Saudi Arabia, India and Turkey, have lower participation rates than most countries at the same income level, but, as noted above, have made progress in increasing the participation of women in the labor force in recent years.

Drawing on the apparent U-shaped relationship evident in Figure 3, commentators going back to Goldin [1]have posited that female labor force participation rates will increase as an economy develops, regardless of country-specific initial conditions and trends. A number of studies have tested the validity of this hypothesis and robustness to different data sets and methodologies. One study finds that the U-shaped relationship is not robust once more advanced estimation techniques (dynamic generalized method of moments (GMM) panel data techniques) are employed [5]. Moreover, earlier findings were sensitive to the use of more up-to-date and accurate labor force data.

Trends based on labor survey data reveal that not all countries have followed a U-shaped path as their economies have grown. This is evident, for example, in labor markets that have started at lower levels of participation, which have been historical impacted by social norms (e.g., Southern Asia and Arab States). At the same time, female labor force participation at higher levels of development (i.e., in high-income countries) stalls at a rate that still represents a gap to male participation rates due to continuing barriers for women’s access to the labor market. Overall, there is nothing deterministic by the process and depends crucially on various factors, including the nature of the growth path itself [2].

Does education increase the likelihood of a woman’s participation in the labor force?

One of the key determinants of labor market outcomes in both developed and developing countries is educational attainment [3]. Education levels of girls and young women have improved considerably in recent decades and should have helped increase opportunities for women to enter the labor market. In many countries, there is a positive relationship between educational attainment and female labor force participation, while in a few economies there is evidence of a nonlinear or U-shaped correlation (e.g. India) [7]. In poorer countries, the most uneducated women are the most likely to participate in subsistence activities and informal employment, while women with a high school education tend to be able to afford to stay out of the labor force. Once women have more than a secondary school education, higher wages pull them to join the labor force, particularly if appropriate jobs are available.

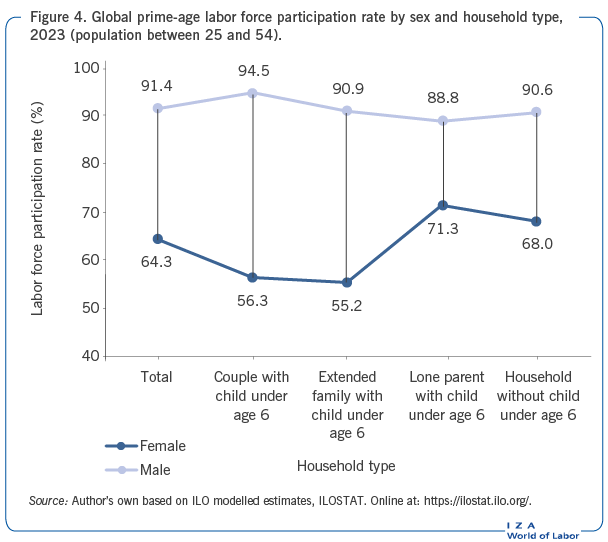

A critical constraint to women’s participation in the labor market is care responsibilities, which still has much greater impact on women than men [8]. ILO global estimates by household type indicate that the female labor force participation rate is the lowest for women in an extended family and with a partner and children under the age of six. Even in the case of households without children under the age of six, women have significantly lower participate rates than men who do not experience the same variation across household types. Women who are lone parents have the highest female labor force participation rates, which reflects the necessity of being employed when managing a household with the lack of other means of support.

Participation is only part of the picture: The quality of employment matters

Studies on female labor participation tend to primarily focus on the binary nature of this labor market indicator. However, it is crucial to understand not only whether women are working or actively seeking work, but also the nature of the work women are able to access.

Overall, the quality of employment and opportunities for better jobs continue to be unequally distributed between men and women, even in countries where there is a lower gender gap in the labor force participation rate. In most developing countries, when women work, they tend to earn less (the well-known gender wage gap), to work in less productive jobs, and to be overrepresented in unpaid family work and other forms of vulnerable work. Employment segregation by gender is prevalent across the world [6].

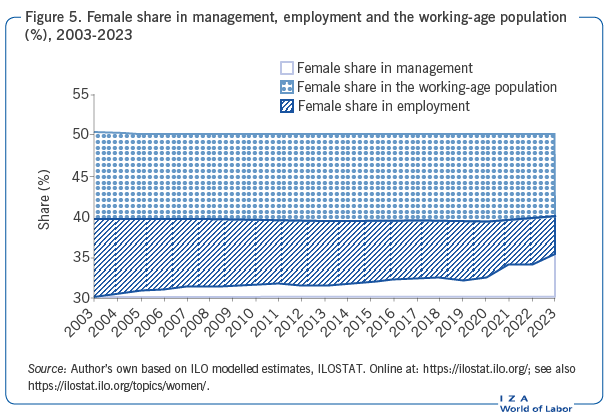

In terms of employment status, more women than men work as contributing family workers, which adds to their labor market vulnerability. The ILO estimates that contributing family work accounts for 19.3% of female employment in low- and middle-income countries, compared to 7.7% of male employment (2023 ILO modelled figures). The good news is the increase in the female share in management, which has increased from 30.2% in 2003 to 35.4% in 2023, even though the share of women in employment (and the working-age population) remained relatively static over this period.

As well documented in the literature, women typically earn less than men, even after controlling for differences in observable worker and job characteristics. Based on a large sample of countries, a review paper finds that the earnings gap between men and women with similar characteristics ranges from 8% to 48% [9]; global estimates suggest an average gap of around 20% [10].

Education plays a critical role in determining the quality of employment taken up by women since it raises the reservation wage (the lowest wage at which a person would accept a particular job) and changes the preferences of jobseekers. One study of women in Indonesia estimates that, compared with having a junior secondary education, having a college education increases the probability of working in a regular job by 25.6% and having a senior secondary education increases it by 10.3% (based on an analysis of 2009 labor force survey data). Women with at most a primary school education were less likely to be regularly employed [3].

Women’s education needs to expand beyond middle school (junior secondary) for their participation in the labor force to increase, especially if they are to work in better quality jobs. At higher levels of education, potential earnings act as a pull factor, helping overcome economic and social constraints.

Limitations and gaps

The literature has (and, increasingly, policymakers have) long recognized that women’s participation in the labor force is poorly measured and underestimated [11]. Though data collection has improved, this remains a major obstacle to the analysis of official statistics collected through labor force and other household surveys. Another limitation arises from survey enumeration. Because of poor training of enumerators, labor force surveys underestimate the participation of women, especially when they are working at home or on the farm. Enumerators can inadequately probe for the economic activities of female members in the household, a problem that is compounded by the fact that men are typically the survey respondents in countries where female labor force participation rates are low.

Time-use surveys have been proposed as a means of gathering more accurate and insightful data on the nature of women’s work in and out of the household, especially in subsistence production and informal employment [11]. The challenge, however, is that time-use surveys are costly and difficult to implement regularly.

Summary and policy advice

The changing nature of women’s participation in the labor force has been a critical dimension of the development process and increasing numbers of women in the labor market have played an important role in driving the demographic dividend and pushing economic growth. However, the relationship between female labor force participation and economic progress is far from straightforward. Though cross-sectional data do indicate that there is a (weak) U-shaped relationship between female labor force participation and GDP per capita, this relationship is not robust and there is not a consistent trend at the country level. Ultimately, women’s employment is driven by a range of multifaceted factors, including education, social norms, and the nature of economic growth and job creation.

Beyond standard labor force participation rates, policymakers should be concerned with whether women can access better jobs and take advantage of new labor market opportunities that arise as a country grows, including those precipitated by technological change, and, in so doing, can contribute to the development process itself. For this reason, policies should consider both supply-and demand-side dimensions, including better quality education and training programs and access to childcare, as well as other supportive institutions and legal measures to ease the burden of domestic duties, enhance women’s safety, and encourage private sector development in industries and regions that can increase job opportunities for women in developing countries.

Particular emphasis is needed on keeping young girls in school and ensuring that they receive a good quality education, beyond secondary level, and are able to take advantage of training opportunities. That, in turn, will increase their chances of overcoming other barriers to finding decent and productive employment.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the anonymous referee(s) and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The responsibility for opinions expressed in this article rests solely with the author, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the ILO. Version 3 of the article fully revises the text, updates the figures and adds some new global estimates. It adds new Key references [4], [8], and [10].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Sher Verick