Elevator pitch

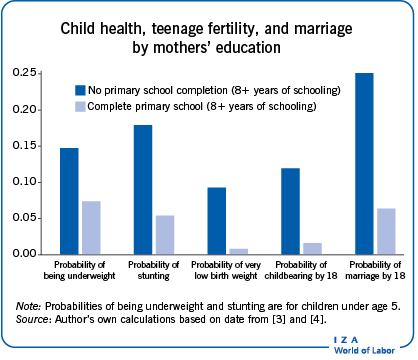

There is a strong link between mothers’ primary school completion (8 or more years of schooling) and better socioeconomic outcomes, such as improved child health and reduced teenage fertility, but establishing causality is challenging. A 1997 compulsory schooling law in Turkey, which extended education from five to eight years, provides a natural experiment to identify causal effects. Empirical evidence suggests that increased female education from such reform significantly improves many socioeconomic outcomes of mothers and their children. While suggested mechanisms include changes in healthcare services utilization and risky pregnancy behaviors, such as smoking, thorough investigation of underlying channels is lacking.

Key findings

Pros

Compulsory schooling reforms such as in Turkey help identify the impact of female education on socioeconomic outcomes like child health and female empowerment.

Schooling reforms can significantly increase the likelihood of completing eight years of compulsory schooling for females, especially in rural areas.

Increased female education from schooling reforms can improve child and maternal health, and reduce teenage fertility and marriage.

Maternal education improves child health via preventive care and reduced smoking and lowers teenage fertility via modern contraceptive use.

Cons

The long-term effects of schooling policy are unexplored, so it is unclear if short-term effects will persist.

Existing evidence does not clarify the mechanisms linking female education to socioeconomic outcomes.

Mixed health outcome findings, partly due to data limitations, prevent policymakers from confirming education’s health benefits.

The effects on other important outcomes, such as mental health, cognitive skills, and poverty remain unexplored.

Author's main message

Educational interventions to improve female education are considered highly effective development policies as benefits include both market outcomes (e.g., labor market participation or wages) and non-market outcomes (e.g., child and maternal health) of women and their children. Understanding the causal link between female education and socioeconomic outcomes is important. Using a change in compulsory schooling in Turkey that significantly increased female education as an exogenous shock, researchers found improvements in child and maternal health, reduced teenage fertility and marriage, as well as enhanced female empowerment. Expanding educational opportunities, particularly in societies with low female empowerment and education rates can provide significant improvements in women’s socioeconomic outcomes and generate long-lasting benefits for future generations.

Motivation

There is a strong link between female education and socioeconomic (SES) outcomes for women and their children, such as child health and fertility [1]. To establish causality, economists have used educational interventions as natural experiments, and Turkey's change in compulsory schooling law (CSL) serves as an ideal case study. Moreover, women in Turkey faced gender gaps in health, education, and economic opportunities and had lower SES outcomes. In 2020, Turkey ranked 130th out of 150 countries in the World Economic Forum’s gender equality index despite being a middle-income country with per capita income of $8,639. In 2011, women aged 25 and older had an average of 6.4 years of schooling and a 28% labor force participation rate, compared to 8.3 years and 72% for men. According to the World Bank, the adolescent fertility rate was 32 per thousand women aged 15 to 19, with infant (child) mortality at 11.6 (14.9) per thousand live births, compared to 47 and 22 (27) in the Middle East and North Africa, respectively. Understanding the causal link between female education and SES outcomes can inform development policy, improving both market and non-market outcomes, like child health. Investigating these effects in Turkey as one leading example could provide insights for countries with similar social and cultural contexts.

Discussion of pros and cons

It has been widely documented in the literature that female education and SES outcomes are strongly correlated both in developed and developing countries [2]. However, observed associations might not suggest a causal link due to unobserved factors like ability and time-preference, affecting both education and SES outcomes. Thus, researchers exploit educational reforms, such as compulsory schooling laws as an exogenous shock to education to identify the causal effects. In Turkey, a nationwide reform of the CSL in 1997 extended basic education from five to eight years, allowing researchers to investigate the causal effects of female education on various SES outcomes, including child and maternal health, teenage fertility, and domestic violence prevalence.

Compulsory schooling law in Turkey

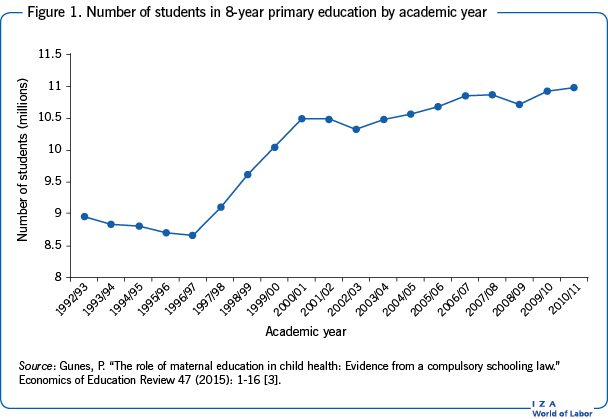

Prior to the educational reform, Turkey required all citizens to complete five years of primary education (free of charge in public schools). In 1997, the Turkish government extended compulsory schooling to eight years to increase the education level to universal standards to enter the European Union. The 8-year basic education program included construction of new schools and additional classrooms to the existing schools and recruitment of new primary school teachers to accommodate the expected increase in enrollment. It also included provision of transportation to children living far from nearby schools to improve access and free textbooks and uniforms to low-income students to ensure all children complete compulsory education. Thus, the education reform had both demand-side and supply-side approaches to promote primary school completion by extending compulsory schooling duration and reducing attendance cost. The CSL significantly increased student primary school participation, particularly for females in rural areas (around 162% for female enrollment in grade six in the first year of the change in the law according to UNICEF). Enrollments in 8-year primary education increased by around 15% between the 1997/1998 and the 2000/2001 academic years (Figure 1).

Several studies have investigated the effects of the CSL in Turkey on female education. While these studies employ different empirical methods and educational outcomes, the findings consistently show that the CSL significantly increased female education. In particular, the CSL increased the probability of completing eight years of primary schooling and years of schooling for women by 15 to 19 percentage points and 0.5 to 1.5 years, respectively [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Evidence on the benefits of the CSL on female education allowed researchers to identify the causal effects of female education on SES outcomes of women and their children.

Effects of female education on child health

A few studies explore the effects of female education on child health and demonstrate that increased female education as a consequence of the CSL improves the health of their children. These studies have used individual-level data from different sources, employed different research design, and explored a wide range of child health outcomes.

To identify the causal effects, one study implements an instrumental variable (IV) estimation, which uses the variation in the exposure to the CSL across cohorts and provinces as an IV (i.e., external shock to education) [3]. In particular, this study exploits variation in the exposure to the change in the educational reform across cohorts and variation across provinces by the intensity of the reform as measured by additional classrooms constructed in the mother’s birth provinces. Using the 2008 Turkish Demographic and Health Survey (TDHS-2008) as the main dataset, the study explores the effects of female education on child health as measured by anthropometric measurements, such as height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores, infant health as measured by birth weight, and maternal health as measured by delivery complications. Findings show that mothers’ primary school completion (8 or more years of schooling) improves child, infant, and maternal health. More specifically, mothers who completed primary school have children with higher height-for-age and weight-for-age z-scores, are less likely to give very low-birth-weight births (referring to children weighing less than 1500 grams at birth), and reduces delivery complications.

Using a similar methodology and the same TDHS-2008 dataset, another study explores the effects of maternal education on other child health outcomes, including the probability of stunting (i.e., children with height-for-age below -2 standard deviations) and being underweight (i.e., children with weight-for-age below -1 standard deviation) [4]. The results show that completing primary school reduces the likelihood of child stunting and being underweight, suggesting that maternal education improves child health.

Another study exploits the number of primary school teachers per primary school age children in the childhood region as an IV to estimate the causal effect of education on child mortality, as measured by the number of children who died before the age of one or five [5]. Using TDHS-2003 and TDHS-2008 data, the study provides some weak evidence that primary school completion of mothers reduced child mortality by reducing deaths before age five, particularly in the first month after child-birth. One reason one does not see strong evidence linking education to infant and child deaths in Turkey could be that such deaths were very rare during the study period. Another reason might be that the analysis underestimated the standard errors because it used fewer childhood regions (only 12) to construct the IV.

An alternative research approach—regression discontinuity (RD)—separates women into groups exploiting a cutoff based on the month and year of birth of the women to determine exposure to the educational reform and compares outcomes of women and their children before and after the reform’s implementation. Employing a fuzzy RD (i.e., using the discontinuity in the cutoff as an IV), another study confirms the positive effects of maternal education on child health [6]. To explore the causal effects, the study uses birth outcomes data from the Turkish Ministry of Health and child mortality data from the Turkish Statistical Institute’s Population and Housing Census 2011. The results show that mother’s primary school completion reduces the likelihood of low-birth-weight births (referring to children weighing less than 2500 grams at birth), premature birth (i.e., children with gestational age less than 37 weeks) and child mortality (having at least one child die before the age of five).

There are several explanations for how maternal education may affect child health. One explanation is that better educated women are more likely to utilize health care services, including formal prenatal visits. The findings of studies in Turkey support this mechanism. For example, mothers who completed primary schooling initiate prenatal care earlier than those who did not [3]. Another study shows that mother’s primary school completion increases the likelihood of antenatal visit during the first trimester of pregnancy [5]. Moreover, education may affect other maternal health behaviors during pregnancy, such as smoking and drinking. Studies support this mechanism, showing that primary school completion reduces the probability of smoking [3], [6].

Besides health care utilization and maternal health behaviors, income might explain the link between maternal education and child health. In particular, education might increase income via increases in maternal earnings or assortative matching (e.g., matching with better-educated and higher-income husbands). Higher income may in turn increase the demand for higher quality children, such as healthier and more educated children, while reducing the demand for quantity of children. While studies in Turkey find no evidence for assortative matching, they suggest changes in fertility behavior, such as increased age at first birth as a potential mediating factor [3], [5].

Other explanations include greater female autonomy in health-related decision-making and resource allocation within the household, greater knowledge about diseases and modern health care service, and increased adoption of modern medical practices due to better maternal education. While evidence for these mechanisms is unclear, one study shows that increased maternal schooling is associated with a higher probability of using modern contraceptive methods [5].

Effects of female education on teenage fertility

Because teenage fertility adversely affects SES outcomes of mothers and their children, understanding the role of female education in teenage fertility is important to policy makers, especially in countries with high teen birth rates and low female education. Again, using Turkey as a leading example, research shows that before the CSL, teenage fertility was very high and female primary education was low. Following the CSL, teenage fertility declined and female primary education increased. Therefore, researchers were interested in whether the decline in teenage fertility was due to the rise in female education from the CSL.

To evaluate the impact of female education on teenage fertility, one study uses variation across cohorts induced by the timing of the educational policy and variation across provinces by the intensity of additional classrooms constructed in the mother’s birth provinces as an IV [4]. Findings show that primary school completion significantly reduces teenage fertility. In particular, mother’s primary school completion reduces the number of births before age 18 by 0.37 births and the incidence of teenage childbearing by around 28 percentage points. The study also shows that it reduces teenage fertility for births before ages 16 and 17. Moreover, findings show that the impact of education on teenage fertility varies across provinces, indicating greater decline in provinces with lower population density and higher agricultural activity. For educated women, reduced motherhood rates may result from delayed marriage or delayed first birth within marriage, especially in Turkey where childbearing out-of-wedlock is uncommon. Empirical findings support the above mechanisms, showing that female education reduces the chances of teenage marriage and delays childbearing within marriage.

Employing a RD empirical research design (i.e., using the discontinuity in the cutoff based on month-year of birth), another study finds that the CSL reduces the probability of giving birth before ages 16 and 17 [7]. Consistent with previous literature [4], results also indicate that the educational policy significantly reduces the number of births before age 18 by around 0.10.

Women’s education may affect fertility through various channels. One channel is the increases opportunity cost of childbearing and child rearing due to higher returns to labor market participation. Thus, better educated women may desire fewer children to focus more on their careers. Moreover, changes in matching outcomes, like educated women matching with educated men could affect women’s preferences for children. While evidence suggests that, at least in Turkey, matching is not the main reason for the link between female education and reduced (teenage) fertility [4], the potential mechanism of labor market outcomes is unexplored.

Increased adoption and effective use of modern contraceptives, along with greater knowledge about them, link female education to fertility. Studies in Turkey show that female education affects fertility partly through better use of modern contraceptives [4], [5]. Education can also change fertility preferences, such as increasing the demand for healthier but less children [4], [5]. Additionally, greater bargaining power in household fertility decisions may drive the effect of education on fertility, though there is no causal evidence for this mechanism.

Effects of female education on other outcomes

Investigating the causal effects of female education on domestic violence may shed light on whether educational interventions can empower women. A relatively recent study explores the effects of female education on various intimate partner violence indicators [8]. Employing a RD design, the results suggest that while increased female education among young rural women increased the incidence of psychological violence and financial control behavior, it did not change the incidence of physical and sexual violence or women’s attitudes towards domestic violence. The study also suggests that the effect of the reform on psychological violence in rural areas may be linked to women working in the nonagricultural sector and earning higher personal income. Similarly, the authors find that the reform reduced the likelihood of physical child abuse, but only for women from rural areas who were abused as children [9]. The results also suggest that improved mental health can explain the findings.

While the effects on health are important for public policy, there is some, but not considerable evidence that female education improves health outcomes of women. A few studies exploiting the CSL in Turkey produce mixed results, possibly due to variations in research design and datasets. For example, one study using cohort exposure to the CSL as an IV finds that increased education reduces the likelihood of being overweight and obese for females and increases the likelihood of self-declared health status being excellent for females [10]. This study acknowledges the shortcoming of mismeasurement error in self-reported height and weight used in the analysis. Conversely, another study using the number of new middle school class openings in each region as an IV finds that female education had no effect on the likelihood of obesity or being overweight [11]. This study uses measured height and weight of women to avoid misreporting, but clear evidence of health benefits is still lacking.

The effects of schooling on other outcomes, such as wages are also examined using the CSL as an exogenous shock to education. Using a fuzzy RD design and the 2002-2013 Household Labor Force Surveys of Turkey, one study shows that the wage return to schooling is low for both genders, but higher for women [12]. The study finds that the benefits of extra schooling were low for the grade levels directly affected by the policy (grades six to eight) and the benefits of schooling are higher in high school than in lower grades. Since a larger share of women were encouraged to finish high school because of the policy, compared to men, returns to schooling were higher for women than for men.

Limitations and gaps

Establishing a causal relationship between female education and SES outcomes is challenging. To identify such effects, empirical studies exploit a change in the educational reform in Turkey as a natural experiment where individuals exposed to the policy are imposed to receive more education. Employing IV or RD design that leverage variations in exposure across cohorts and provinces, these studies could explore the causal effects of female education on various SES outcomes of women and their children. However, one drawback of exploiting the CSL as an exogenous shock is that the estimated effects apply only to women for whom the policy was binding (i.e., women who completed eight years of schooling, but would not have completed eight years of schooling in the absence of a change in the CSL). Thus, findings may reflect so called local average causal effects among a subpopulation of women which could differ from population averages. While compliant women were more likely of Turkish ethnicity and from rural northern and eastern Turkey, they share certain characteristics, such as type and region of residence, with the average women [3]. Another limitation is that most studies do not explore how returns to education vary by characteristics, like family background. In addition, existing research focuses on primary school completion (at least 8 years), lacking information on returns to an additional year of schooling. Finally, the CSL primarily targeted universal primary schooling, limiting the investigation of causal effects from different schooling margins, such as high school completion on SES outcomes.

Furthermore, current literature in Turkey focuses on young women (ages 18 to 30), leaving the long-term effects of the policy unexamined. For example, the questions of whether short-term effects persist in the long run and how they relate to completed fertility remain unanswered. Because the effects of education can unfold over the lifetime of women, exploring life-cycle effects is essential for understanding the relationship between women’s education and SES outcomes. Moreover, the lack of clear health benefits for relatively younger generation (ages 18 to 34) does not rule out positive health returns to education later in life. Also, explored outcomes in the literature, such as body mass index may not capture long-term overall health and well-being.

A further limitation is the lack of precise mechanisms through which female education affects SES outcomes. While some empirical findings suggest potential channels, many others and their relative importance remain unexplored. For example, it is still unclear whether mothers’ education affects their children’s health through increased income from higher maternal earnings or better partners, reduced risky behaviors during pregnancy, such as smoking and drinking, improved healthy diet and nutrition, greater healthcare services utilization, or increased women’s empowerment. Understanding these channels would help policymakers design more effective interventions.

Finally, the effects of both female education and the educational reform on important outcomes like mental health, poverty, cognitive skills, and crime remain unknown. Exploring a wide range of non-market and market outcomes would highlight the benefits of education and clarify whether investments in female education are effective development tools.

It is important to note that there is limited evidence from developing countries, partly because successful educational reforms that could serve as exogenous shocks are difficult to identify [13]. However, the education reform in Turkey has provided a valuable natural experiment for examining the causal relationship between education and various SES outcomes, offering unique features that distinguish it from many other educational reforms. As a result, there has been growing interest in exploring the effects of these reforms specifically in Turkey. More research in developing countries is needed to further understand the causal effects of education on SES outcomes to generalize the results.

Summary and policy advice

A wide range of educational interventions, such as reducing the cost of attending school through improved access to school and making basic education compulsory have been used as development tools in many developing countries [13]. A few studies have examined the causal effect of female education on SES outcomes using different educational reforms as exogenous shocks in developing countries (e.g., Indonesia and Nigeria), showing that female education improves child health and reduces early fertility [13].

In 1997, Turkey implemented a nationwide educational policy that increased compulsory schooling from five to eight years to achieve universal primary education. Unlike many reforms that focused only on supply-side approaches, such as school construction projects and providing teachers, particularly in disadvantaged areas, the CSL in Turkey entailed both demand-side and supply-side aspects. In particular, the CSL in Turkey extended the duration of compulsory schooling from five to eight years and encouraged compliance with a new Primary School Diploma for only those completing the 8th grade, addressing demand-side barriers. The program also included several supply-side aspects, such as school construction and cost reductions through free textbooks, uniforms, and transportation. Such comprehensive laws can be crucial for increasing female education, especially in societies where girls face significant cultural and financial barriers to attending school.

Turkey’s educational reform thus works as an ideal role model which significantly increased educational achievement, particularly for women. Empirical findings using this reform as a natural experiment show that higher female education led to improved SES outcomes of women and their children, such as better child health and reduced teenage fertility and marriage. Several mechanisms linking education to these outcomes were uncovered, such as earlier preventive care, increased antenatal visits during the first trimester, delayed first births, and reduced smoking. Additionally, greater use of modern contraceptives links female education to teenage fertility. However, limited evidence on health benefits and a lack of data on various health outcomes hinder strong conclusions about long-term effects.

The significant benefits of female education, in both market outcomes like labor market returns and non-market outcomes, such as child and maternal health underscore the importance of educational interventions, especially in societies with high gender inequality and poor female SES outcomes. The compulsory schooling reform in Turkey effectively increased primary school completion, particularly among women, leading to substantial improvements in many SES outcomes. Moreover, the reform may also provide intergenerational benefits for the children of those who attain higher education levels. Therefore, evidence in Turkey suggests that increasing compulsory schooling could be used as a development tool, especially in societies with low female empowerment and education rates. Furthermore, findings suggest that policymakers might focus on expanding educational opportunities for subpopulations where the returns to education would be the highest, such as low-income areas to reduce disparities in socioeconomic outcomes. However, policymakers must assess whether the benefits of the interventions outweigh their costs to evaluate the effectiveness. Conducting a cost-benefit analysis for various educational policies and comparing their cost-effectiveness to alternatives remain a challenge for policymakers.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the anonymous referee(s) and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [3] and [4].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Pinar Mine Gunes