Elevator pitch

Can entrepreneurship programs be successful labor market policies for the poor? A large share of workers in developing countries are self-employed (mostly own-account workers without paid employees, often interchangeably used as micro entrepreneurs). Their share among all workers has not changed much over the past two decades in the developing world. Entrepreneurship programs provide access to finance (or assets) and advisory and networking services as well as business training with the aim of boosting workers’ earnings and reducing poverty. Programs vary in design, which can affect their impact on outcomes. Recent studies have identified some promising approaches that are yielding positive results, such as combining training and financial support.

Key findings

Pros

Self-employment continues to be a major source of employment and earnings in developing countries, and enhancing the productivity of the self-employed is important for poverty reduction.

Entrepreneurship programs aim to raise micro entrepreneurs’ productivity by addressing key constraints.

Combining business training and financing along with supplemental services seems more effective than stand-alone programs in promoting labor market activities among poor self-employed workers.

Providing support customized to the needs of participants improves program effectiveness.

Cons

Entrepreneurship programs for the poor often show impacts that are small and not statistically significant, and the programs’ longer-term sustainability is unclear.

Improved business practice or knowledge does not automatically lead to business growth or job creation.

Little information is available on the details of implementation quality and cost of the intervention, making comparing programs difficult.

Author's main message

Some features of small-scale entrepreneurship programs are associated with successful program impacts. Among them are accommodating the design to the needs of the target group. A comprehensive approach combining skills training and access to finance often with other supplemental services is more effective in helping small-scale entrepreneurs succeed in the labor market than stand-alone services. Business training can help small-scale entrepreneurs set up businesses and improve business practices, while customized support and services can improve overall program effectiveness.

Motivation

A majority of the workforce in developing countries is self-employed, usually in low-paying own-account work that keeps them in poverty. The share of the self-employed has remained stubbornly high, particularly in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Thus, fostering entrepreneurship is widely perceived to be critical for expanding employment and earning opportunities and for reducing poverty. Interventions to promote entrepreneurial activities, particularly for small- scale businesses, are increasingly being implemented in developing countries.

Such small-scale entrepreneurship programs vary in their objectives, target groups, and implementation arrangements, and they often include multiple types of interventions reflecting the specific constraints to entrepreneurial activities that each program aims to address. An early meta-analysis synthesizing the results of rigorously evaluated entrepreneurship programs suggested some promising design and implementation features for program success, using studies conducted before 2012 [1].

Since then, many evaluations to examine the effects of entrepreneurship programs have been carried out. This update is to review more recent evidence and lessons learned for program design and implementation, and identify future areas of research.

One report focusing mostly on livelihood programs built on safety nets [2],another report focusing on youth employment programs [3], and one study focusing on entrepreneurship training [4] are major meta-analyses cited in this article.

Discussion of pros and cons

Characteristics of self-employed workers in developing countries

Lower income countries generally have a higher share of self- employed workers in the labor market, particularly farmers and own-account workers, referred to here as small-scale entrepreneurs. In sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, more than three-quarters of workers are farmers or non-agricultural self-employed workers ( Figure 1). Small-scale entrepreneurs tend to be older and less educated than wage employees, with more volatile labor market activities and a greater likelihood of exiting the labor market rather than moving to other forms of employment. Consequently, the chances of living in poverty are higher for small-scale entrepreneurs than for wage employees. Indeed, close to 70% of self- employed workers worldwide live in poor households and strive to make a living with their labor-market activities [5]. During the large labor market shock of the COVID-19 pandemic, the share of the self-employed increased particularly among young workers [6].

Scope of small-scale entrepreneurship programs

Small-scale entrepreneurship programs Small-scale entrepreneurship programs aim to promote entrepreneurial activities and more productive businesses. The programs tend to address constraints facing individual workers, such as missing skills, entrepreneurial mind-sets, social capital, and access to credit. The goal of these programs is to improve workers’ livelihoods through self-established businesses more than it is to foster innovative enterprises to drive economic growth. The programs seek to affect several common outcomes of interest [1]:

labor market activities such as business start-up and expansion and increased self-employment;

labor market income and profits;

business practices and knowledge that can affect business performance, such as record-keeping, registration, and separation of individual and business accounts;

business performance, often captured by revenues and the scope of such business activities as sales, number of employed workers, and size of inventories;

financial behavior, such as acquisition of business loans, saving accounts, and insurance plans that could affect the resource allocation of businesses;

mind-set, attitudes toward risk, confidence and optimism, and time preference that may be related to entrepreneurial traits.

Identifying the target group

Small-scale entrepreneurship programs help would-be entrepreneurs set up a business and existing entrepreneurs improve their performance. As do other social programs, small-scale entrepreneurship programs can be directed at specific demographic groups, such as youth and women, or social category, such as social assistance beneficiaries and micro-credit clients. In addition, information on employment status and region (such as farmer and urban informal worker) can also be used for targeting, to take into account the differences in businesses and forms of employment across urban and rural areas.

When a target group is identified—such as self-employed women, out-of-school youth, social assistance beneficiaries, and micro-credit clients—profile studies are needed to understand their skills, capabilities, and constraints. Some combination of surveys, tests, qualitative interviews, and assessments can be used to better understand potential participants [7]. Recently, programs have increasingly used tests to objectively measure cognitive skills (such as the Raven test and the Digit-span test), non-cognitive skills (such as the entrepreneur self-test), and basic skills (numeracy and literacy tests) [8].

Selection of activities for support

Entrepreneurship programs generally require that potential participants apply for the program and describe their business idea and plan. Some programs select participants based on the viability of their business proposal or on the type of activities planned. Others use the business proposal to assess the competence of applicants and identify their needs. Still others use the business proposal for both purposes. However, this kind of approach may not be appropriate when the majority of potential participants are unskilled, vulnerable workers who do not see their work as entrepreneurial activities or themselves as business people. Further, many of them may not have identified a specific business idea let alone written a business plan.

A less common model is a collective approach in which ideas are identified by the program organizers, often social enterprises, non-governmental organizations, or private-sector entities [9]. In this model, program organizers identify business opportunities based on pre-program market analysis such as sector mapping and demand surveys. The program formulates business plans based on the availability of natural resources, infrastructure, and human capital and on the condition of the regulatory environment. The program then recruits individual workers or groups such as cooperatives or associations to participate in the pre-identified business areas. Participants are expected to develop or continue their business within the parameters set by the program while benefiting from the program organizers’ collective knowledge and know-how, connections to local value chains and markets, and synergy from economies of scale. Micro-franchising and value chain integration models provide examples of this approach.

Technical components

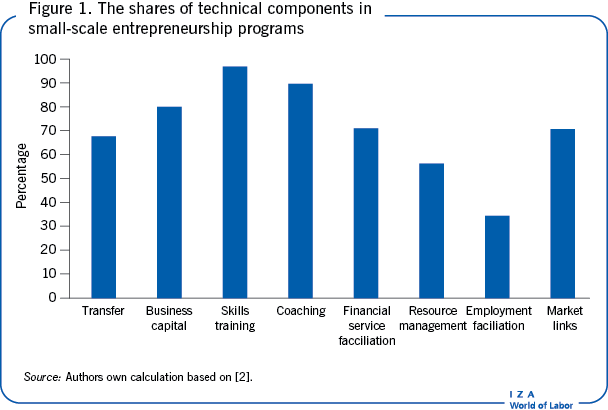

Programs typically include one or more of four technical components: training, finance (business capital), advisory services (such as coaching), and networking. Training is provided to strengthen technical skills in entrepreneurship and financial literacy as well as specific vocational and occupational skills. Access to finance is facilitated through the provision of business capital or regular cash transfers. Advisory services include coaching to build soft skills such as grit, positive mind-set, resilient attitudes and problem solving, facilitation of financial services such as savings and insurance products, natural resource management support, and counseling for wage employment opportunities. Finally, market access and networking services aim to support value chain integration. According to a comprehensive review of Economic Inclusion programs, almost all programs include some sort of skills training; coaching and business capital provision are quite common as well (Figure 1).

Training

Training covers a range of skills including technical, vocational, business, managerial, and financial skills as well as literacy and numeracy and life skills [4]. Recently, technology adoption and entrepreneurial mind-sets are increasingly becoming part of training. Training components vary in duration, intensity, and delivery arrangements depending on training type and objectives. A general principle in providing training services is to ensure that participants acquire prerequisite skills (basic literacy and numeracy, business awareness, and financial literacy) before moving up to higher level skills (technical, vocational, business, managerial, and financial skills). Gaps in literacy and numeracy among participants are typically a primary barrier to acquiring other skills. Unless these gaps are addressed, training in advanced areas will not yield the desired impacts.

Financing

Limited access to credit is often one of the most binding constraints to entrepreneurship. Many small-scale entrepreneurship programs provide financial support to ensure that participants have the working capital, assets, and equipment they need to get started in business. Many use cash grants of safety net programs for initial capital [2]. In-kind transfer of equipment and tools, assets, and workshops with basic business infrastructure (electricity, water, basic equipment) are also used to help entrepreneurs manage their resources. A general trend is that policy attention to financial services shifts over time from loans to a more general agenda of financial inclusion—making financial services accessible to disadvantaged or low-income people—and from micro-finance to exposure to diverse financial products for managing risks.

Advisory services

Unlike training programs, which are generally offered at a set time, for a set duration, and on a specific topic, advisory services are usually offered on a continuous basis with more customized content, at least during the first stages of a small-scale entrepreneurship program. The advisors can be experts, peers, or mentors in various business areas. Their roles range from answering specific business-related questions and guiding participants in making strategic decisions to facilitating access to other resources for support. Many programs, particularly in rural areas among agricultural workers and self-help groups, rely on lead farmers and group representatives. They receive extensive training on new techniques, products, quality measures, or business skills, which they can then share with other farmers and members of the self-help group. Other programs work with international and local professionals and role models as well as social entrepreneurs to provide advisory services. An example from Indonesia shows that curating local knowledge and portraying positive local role models were effective in promoting urban entrepreneurs to adopt good business practices [10]. The right type of advisory services in each case will likely depend on business needs and the characteristics of participants. For instance, while providing financing, advisory services or behavioral design can address some behavioral challenges (e.g. self-control, procrastination, present-bias or myopia) to ensure the productive use of financing. Such intervention can lead to increases in savings and improved profits [11].

Networking

Networking builds up social capital, which is important for gaining entry to markets and operating a business. Networking is particularly useful for connecting to other businesses at a similar stage of development and in similar areas of production (“horizontal linkages”) and to other businesses along the value chain (“vertical linkages”). Horizontal linkages can be promoted through activities in associations, cooperatives, and other forms of cooperation between both complementary and competing businesses. For instance, a self-employed electrician can form a cooperative with other electricians in the area to pursue a larger contract with a construction business while continuing the small business. Alternatively, or in addition, the electrician can cooperate with carpenters, plumbers, and other tradespeople to collectively provide restoration or remodeling services. In both cases, participants can take advantage of economies of scale, group sharing of responsibility, and strengthened bargaining powers in business. Vertical linkages can facilitate participants’ close collaboration with firms engaged in complementary activities in a different stage of the production process or even their transition into one of those activities. Promotion of horizontal linkages is relatively common in small-scale entrepreneurship programs, while vertical linkages are not as common but are increasing. Networking support can be particularly useful for female entrepreneurs who may lack market connections.

What is known about the impacts?

Only a few small-scale entrepreneurship programs have had a built-in monitoring and evaluation component, and even fewer had been subject to scientifically rigorous impact evaluations when an early meta-analysis was conducted [1]. Over time, many studies have rigorously evaluated the impacts of entrepreneurship programs and a few meta-analyses analyzed their effectiveness. Key findings in these studies are summarized as follows.

First, entrepreneurship programs do generate modest but positive returns. In many cases, they are better in increasing the likelihood of employment than other labor market interventions such as employment service [3]. The results are driven by higher returns of these interventions in countries where private sector wage employment is quite limited.

Second, bundled packages tend to work better than stand-alone interventions. Even if the bundling may increase the unit cost of the intervention, addressing multiple constraints generates higher returns. For instance, cash grants combined with behavioral interventions or training and group formation were more effective than cash alone (as commonly discussed as “cash plus”) [2]. Similarly, asset transfers were more effective when training for market linkages was provided. These findings suggest that training alone or financing alone may not be sufficient to address complex constraints faced by small-scale entrepreneurs in developing countries [1].

Third, services are promising when designed and tailored for specific groups of the population such as women and youth to address their additional challenges. For instance, Kenya’s Gender and Enterprise Together (GET Ahead) program combines standard business training topics (e.g. record keeping, separation of business and household finances) as well as basic numeracy and literacy with gender related contents. A rigorous evaluation found strong impacts on sales and profits of women entrepreneurs three years after the intervention [12]. Moreover, support for networking and providing role models can also be effective particularly for female entrepreneurs.

Fourth, how services are delivered can affect the effectiveness. For instance, beyond classroom-based training, incorporating appropriate pedagogical approaches and supplementary services for the poor and vulnerable (mostly subsistence entrepreneurs) could help. Personal initiatives to build entrepreneurial mind-set or simplified rule-of-thumb [13] rather than sophisticated technical skills can enhance the effectiveness of the programs.

Limitations and gaps

The review studies describe the main features of current entrepreneurship programs and highlight some design elements that appear promising for improving the livelihoods of vulnerable workers. Over time, an increasing body of studies have examined the effects and costs of entrepreneurship programs, assessing their returns and cost-effectiveness. While promising results are emerging, it will require some time to accumulate the evidence on these programs’ longer-term effects. Furthermore, detailed descriptions of program and implementation quality across programs should be better understood to examine how much of the difference in outcomes and impacts is driven by implementation quality.

Summary and policy advice

Small-scale entrepreneurs who struggle to make a living are common in developing countries, and entrepreneurship programs for them will continue to be an important policy tool. The main policy objective of such programs is to improve the livelihoods of vulnerable entrepreneurs by teaching them relevant skills and helping them access the financing needed to improve their earning opportunities. The fundamental question concerns which interventions and combinations of programs are most effective in enabling the poor to start up and expand their business. Combinations of training and financing as well as supplemental services, despite higher unit costs, are more effective in yielding greater returns than providing only training or only financing. Providing business training combined with behavioral design and promotion of entrepreneurial mind-sets are promising in helping small-scale entrepreneurs set up businesses and improve business practices.

Moreover, when designing a new program, policymakers need to consider how to identify target participants, which businesses and activities to support, what core interventions to include, and what types of institutions will provide service delivery. Using an existing social assistance program for targeting and identifying the poor and facilitating their transition to entrepreneurship can be a good starting point. Profiling and understanding the skills and constraints facing potential participants are critical. Knowledge of the profiles of participants and their aspirations can guide the selection of program components, which can include a combination of fundamental skills (basic numeracy or literacy), core occupational skills, soft skills, and business and financial skills. Implementation arrangements, likely involving training providers, financial institutions and local professionals, should be established once the design is determined. Finally, policymakers should also ensure that the programs incorporate a robust monitoring and evaluation system, so that the impacts and cost-effectiveness can be properly assessed.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of this articles discusses new arguments, adds one new Further reading as well as new Key references [2], [3], [4], [6], [8], [10], [11], and [12].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles. The analysis and conclusions expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of the World Bank.

© Yoonyoung Cho

Small-scale entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship programs

Source: Schoar, A. “The divide between subsistence and transformational entrepreneurship.” In: Lerner, J., and A. Schoar (eds). International Differences in Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010; pp. 57–81.