Elevator pitch

Employment tribunals or labor courts are responsible for enforcing employment protection legislation and adjudicating rights-based disputes between employers and employees. Claim numbers are high and, in Great Britain, have been rising, affecting both administrative costs and economic competitiveness. Reforms have attempted to reduce the number of claims and to improve the speed and efficiency of dealing with them. Balancing employee protection against cost-effectiveness remains difficult, however. Gathering evidence on tribunals, including on claim instigation, resolution, decision making, and post-tribunal outcomes can inform policy efforts.

Key findings

Pros

Employment tribunals and other labor courts are important institutions for enforcing workers’ legal rights and protections.

The incidence of claims—notably for unfair dismissal—rises during economic downturns and varies with other factors, including the extent of unionization.

Settling cases before hearings are held depends on parties’ expectations about what the adjudicated decision will be and on conciliation interventions.

Tribunal judgments reflect social and economic factors as well as legal and procedural compliance.

Cons

High numbers of claims place pressure on the tribunal system and can result in significant costs to both sides in the case and to the state.

Because tribunals are charged with enforcing employment protection legislation, they have been criticized for having a negative impact on labor markets.

For a small number of claimants, most notably those whose cases are dismissed without a hearing, there appear to be adverse labor market consequences from seeking redress through tribunals.

Author's main message

Employment tribunals and labor courts have a central role in enforcing employment protection laws and safeguarding other worker rights. What is currently understood about claim instigation, conciliation, and adjudication suggests possible alternatives to the deregulatory dynamic that has emerged in several countries. Improving the quality of information and support available to parties in disputes and working with small firms, which may lack awareness of legal requirements and engage in more informal employment relations, offer promise for improving the labor dispute settlement process without compromising worker rights.

Motivation

Protection of statutory employment rights—such as those related to employee dismissal on the basis of capability/conduct, redundancy, or discrimination—require independent adjudication of disputes between employer and employee about alleged violations. In Great Britain (i.e. the UK excluding Northern Ireland, which has a separate system), this adjudication is the role of employment tribunals. Other advanced economies have similar labor courts. Legal and institutional arrangements vary.

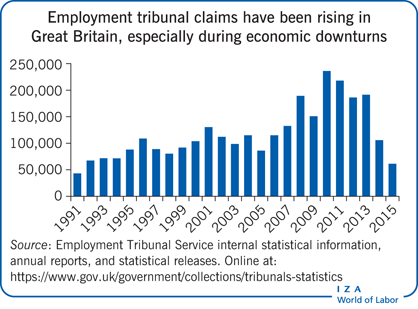

In contrast with most European countries, where caseloads have been stable or falling, in Great Britain volumes have risen sixfold since the early 1980s [1]. Although numbers and rates of claims are as high or higher elsewhere, the upward trend in Great Britain has made this an active policy area for successive governments [1]. Recent reforms have also reflected a concern—shared with policymakers elsewhere—about the adverse impact on business and job creation arising from enforcement of employees’ rights, most notably around dismissal, especially with the high unemployment rate after the 2008 financial crisis.

Because the British debate is especially polarized, this article focuses on employment tribunals there, drawing on wider international evidence where available.

Discussion of pros and cons

Recent policy reform in Great Britain

With employment tribunals having responsibility for enforcing aspects of employment protection legislation, recent policy reforms have concentrated largely on that role. Critics cite the risk that costly litigation reduces business flexibility and deters hiring, inhibiting economic growth and recovery. This remains a controversial topic, although it is worth noting that most of the empirical analysis to date—both in Great Britain and elsewhere—has focused on the extension of rights (through legislation) rather than on their enforcement and the institutions responsible for enforcement.

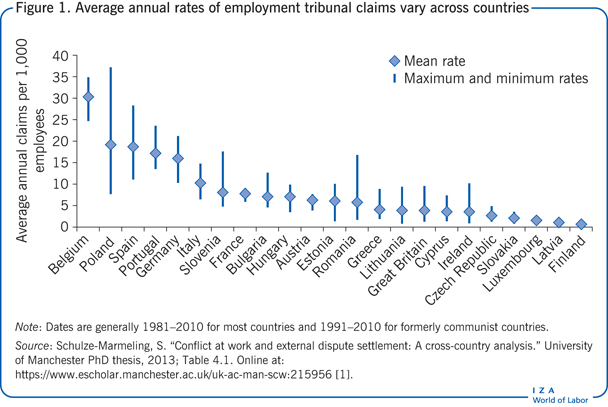

British claim volumes have grown during two main periods: in the 1990s, with the expansion of the range of legislated employee rights; and in the mid-2000s, with the increase in (primarily) equal pay claims involving multiple claimants. Structural differences across countries, such as in the mechanisms for bringing claims and in the propensity to litigate, make it difficult to compare rates. But as Figure 1 shows, claim incidence in Great Britain still appears relatively low.

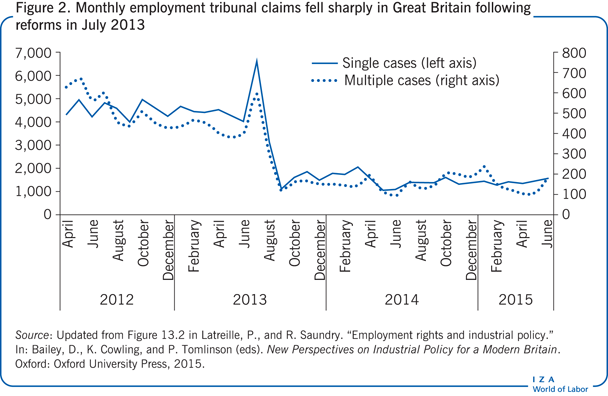

Changes since 2012 in Great Britain include introducing fees for bringing and hearing claims (July 2013), reinstating the previous (longer) qualifying period of two years for eligibility to bring unfair dismissal claims (April 2012), and shortening the consultation period for mass layoffs (April 2013). A new employee status was established (September 2013), known as “employee shareholder,” that allows employees to forgo certain employment rights, including claims of unfair dismissal, in return for a minimum shareholding in the firm. And since April 2014, potential claimants are required to notify the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service (Acas) of intention to file and to consider “early conciliation” before doing so.

Imposing a fee of up to £1,200 for bringing and hearing claims—much higher than in most other countries—is the most noticeable change. Administrative data reveal that the impact on claim numbers has been considerable, with claims falling by about two-thirds (Figure 2). An initial sharp rise in the number of claims immediately before the fees were introduced but after they had been announced was followed by a steep reduction. Although fees were reduced or waived for people on low incomes or benefits, the reforms have been criticized by some as limiting access to justice.

Great Britain is not alone in trying to reform its employment rights adjudication system, however. Australia, New Zealand, and some other OECD countries are also revamping state-sponsored arbitration of employment dismissal disputes, with a similar emphasis on measures to strengthen job creation and business efficiency [2]. The challenge for policymakers is to balance appropriate employee protections with efficiency gains through adjustments to the enforcement apparatus.

A framework for the evidence

The discussion of the evidence that follows is structured around the life-cycle of employment tribunal claims—instigation, conciliation, and determination. A small amount of evidence also exists for post-claim experiences.

Claim incidence and instigation

Policymakers concerned about the number and growth of employment tribunal claims need to understand how claims are initiated. An early study modeling claim initiation as an economic (cost–benefit) process, identifies two stages: the incidence of justiciable events (where legal redress might be sought) and the probability that, conditional on such a “trigger” event occurring, a tribunal application results [3]. The model predicts that the number of justiciable events depends on the costs of compliance for employers compared with the costs that could arise in the event of a claim. This trade-off reflects product and labor market conditions and the economic cycle and thus such factors as unionization, industrial structure, and the size distribution of firms. For their part, potential claimants must weigh the expected gains from a successful claim against the financial and other costs of pursuing redress through an employment tribunal. For potential claimants, the key drivers are the chance of winning their case, the potential value of any penalty awarded by the tribunal, what kinds of support are available (including representation), and the chance of obtaining a new job following dismissal.

Empirical studies have used both aggregate national or regional time-series data and individual or firm cross-section data. One study using aggregate British national time series data for 1972–1997 for unfair dismissal and regional panel data for 1985–1997 for five claim categories reports broad support for the predictions discussed in the previous paragraph [3]. Unfair dismissal claims, for example, rise with previous (lagged) aggregate success rates (a proxy for the probability of claimants’ success), while sex and race discrimination cases are sensitive to the size of awards. These findings indicate that claimants respond rationally to calculations about the expected value of potential claims. There is also some evidence—varying across claim types—of a role for aggregate demographic and industrial structure variables such as gender and small-firm employment, including unionization. Unionization, for example, is negatively correlated with several types of claim, a finding subsequently confirmed for other countries [1].

Several studies have examined how claims vary with the economic cycle. For example, unfair dismissal claims might be expected to be countercyclical, rising during economic downturns. Larger numbers of dismissals during a downturn may reflect attempts by employers to avoid the costs associated with declaring employees redundant; a downturn may also increase the opportunity cost of dismissals, which depends on unemployment and other benefits. There is also evidence that judgments are more likely to favor workers during recessions, which may further increase the propensity to claim [1].

While one British study fails to find a statistical relationship between the number of claims and the unemployment rate [3], the consensus in the international literature is that claim incidence is countercyclical. For example, a study for Great Britain and Germany finds that claims rise with the unemployment rate and fall with an increase in job vacancies [4]. The negative relationship between claims and vacancies is confirmed in subsequent analyses that variously include France, Germany, Spain, and Great Britain and in a wider comparative study using panel data for more than 20 European countries that includes data on the level and changes in the unemployment rate [1]. Such cyclical effects on claim volumes typically dominate the effects arising from changes in the legal and regulatory framework, with the exception of additions to the range of grounds for bringing claims [4].

Whereas studies based on national and regional panel data provide an indication of patterns and movements over time in the number of claims filed, studies based on individual or firm-level cross-sectional data permit a fuller examination of the role of demographic and structural factors by exploiting variation across organizations. A challenge, however, is that data are not readily available linking justiciable events to subsequent decisions by employees and employers throughout the claims process.

In Great Britain, for example, the Fair Treatment at Work Survey provides evidence on individual problems at work and responses to these problems. But even with approximately one in six dismissed employees filing a claim, the subsample is too small to permit meaningful analysis. Firm-level data, such as the Workplace Employment Relations Survey, typically include only whether (and possibly how many) claims were made, not individual events and claims or their outcomes. Finally, data at the claim level, as in the Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications, by definition consider only events for which a claim has resulted and are thus subject to potential selection bias—not all breaches of employment rights give rise to claims, and those that do may differ systematically (for example, in case strength and party characteristics) from those that are not pursued.

Despite these caveats, analyses of such data provide some informative insights. For example, an early study in 2000 finds that unionization is associated with lower rates of workplace disciplinary and dismissal sanctions but not with lower rates of complaints to employment tribunals [5]. However, subsequent studies of the relationship of unionization to claims show mixed results, probably reflecting differences in time period, measurement, and model specification; though none of the studies finds a statistically positive relationship between unionization and other collective industrial relations institutions on the one hand and claim frequency on the other. In fact, several studies report the opposite, suggesting that even though unions may support workers in prosecuting unfair dismissal claims, they also help in resolving disputes at the workplace before they reach the claims stage [1]. This relationship is likely to be more evident in the public sector, where union presence is greater and where there is evidence of lower employment tribunal claim rates than in the private sector.

On organizational size, evidence is again mixed. A cross-sectional study mapping aggregated Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications data to small business data suggests that small firms face more claims relative to their size, with these claims being of different types than claims faced by larger firms, especially for disputes concerning payment of wages [6]. The evidence also suggests that procedural compliance, such as providing disciplinary warnings and completing internal disciplinary procedures—typically weaker in small firms—does not appear to protect firms against claims, even if it makes losing less likely (as discussed below). Nor does the limited evidence based on cross-sectional firm-level data suggest that mediation and other more informal methods of dispute resolution lower rates of discipline and grievance or lead to fewer employment tribunal claims. Indeed, the contrary may be true, possibly reflecting that mediation is a response to rising levels of conflict and litigation.

Pre-hearing resolution

An important feature of tribunals, as of civil courts, is that only a proportion of cases ever reach the final adjudicatory stage. While this proportion varies across countries, most claims (around 80% in Great Britain) are resolved before that stage: dismissed on technical grounds, withdrawn by the claimant, or settled by the parties, often with the assistance of conciliation and arbitration institutions, which have been established in many countries in recognition of the private and social benefits of reaching resolution before the hearing stage.

Key to understanding models of claims settlement is the concept of the “contract zone”—the range of outcomes that both parties prefer to the uncertainty of adjudication by an external agency. Theoretical models of claims settlement in civil litigation cases emphasize the role of expectations, information imbalances (asymmetries) between parties, and risk aversion, concepts of clear relevance to employment tribunals.

But few studies have explored these issues directly in the case of labor courts and employment tribunals. One study, using survey data on individual claims in Great Britain, finds that settlement offers are positively related to Acas intervention (conciliation) and to expectations of success [7]. Settlement offers were more likely in manufacturing, construction, wholesale/retail, and transport and communication industries than in hotels and catering, financial services, and public administration and other services (though other studies find no evidence of industry variation in pre-tribunal resolution rates). Acceptance of settlement offers by claimants is also enhanced by Acas intervention but negatively related to expectations about the amount claimants would receive if the case were adjudicated relative to the amount of the settlement offer. A limitation of the study, however, is that the employers and claimants in the study are unmatched, so it is not possible to control for the quality of cases presented or for selectivity bias. But the results are intuitively plausible and consistent with the idea that parties are systematically over-optimistic about their chances for success through adjudication. Thus, the results suggest an important role for measures aimed at bringing realism to parties’ expectations (“de-biasing”). There is evidence elsewhere that having legal and other forms of representation may also make (private) settlement of claims more likely.

Given the pivotal role of the contract zone in theoretical models of settlement, an alternative approach is to estimate the zone’s monetary size, composition, and distribution between the parties to assess the potential burden of statutory employment law on economic efficiency and income redistribution (from employers to workers). Such an analysis goes to the heart of the tension between efficiency and fairness that policymakers must resolve. A study using Australian cross-sectional data reports the average monetary size of the contract zone to be approximately 16% of the average annual wage cost, with employers saving around 11.5% of that cost (slightly more than half the cost of proceeding to adjudication instead), and employees obtaining around 8% (cost savings of 4.2% plus their threat point or fallback position; that is, the outcome they expect to obtain in the absence of a negotiated settlement) [8]. On that basis, estimated costs are modest, a finding confirmed in later work drawing on survey data to estimate firing costs directly.

Some countries have implemented policy reforms to promote early resolution of employment disputes. For example, measures in Great Britain in the last few years have encouraged mediation, including a pilot to fund mediation training for employees in smaller enterprises and thereby create two regional networks of mediators, introduction of the early conciliation scheme by Acas, and judicial mediation. Other changes were introduced even earlier, in 2004, such as limiting the time for conciliation (to exploit “deadline effects”) and prescribed requirements for discipline and grievance processes (to promote earlier communication and resolution), but failed to deliver the hoped-for effects and were abandoned.

Most of these changes, although subject to initial regulatory impact assessments, have not undergone more robust, formal evaluation. The judicial mediation pilot is an exception. In this initiative, legally qualified judges and lay adjudicators acted as independent third parties seeking resolution of discrimination claims brought in 2006–2007. Unlike the statutory conciliation function—which is conducted largely by telephone—judicial mediation is delivered face-to-face, with judges in a facilitative rather than evaluative or directive capacity. The process is voluntary and conducted by a different judge from the one who would hear the case if it proceeded to a hearing. Early neutral evaluation by judges drawing on their legal expertise and experience might provide a strong, independent signal of the likely outcome at hearing. The evaluation study, using rich administrative data augmented by survey data from both parties, suggested that resolution rates and timescales of discrimination claims under the judicial resolution pilot were statistically no better than those delivered by conciliation and involved a net cost to the taxpayer [9]. Despite this finding, the scheme was extended nationwide on the basis of high user satisfaction. Recent changes now impose a fee for this service, making it likely to fall into disuse before it can provide more evidence on its potential usefulness as an alternative to adjudication and also to other forms of conciliation.

Hearing outcomes

Central to employment dispute settlement models are expectations about the decisions that judges and adjudicators are likely to reach. Studies in a range of countries have examined the determinants of these decisions. An early example for Great Britain, using Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications data, finds that compliance with procedural requirements, such as providing disciplinary warnings and completing internal disciplinary procedures, can affect liability determinations in unfair dismissal cases, with the size of awards also being determined in accordance with the regulations relating to the claim type and the circumstances of the case [10].

Gender and firm size have often been found to have a determining influence. For example, consistent with the US arbitration literature, women are found to be more likely to win than men are, even after studies control for procedural compliance (and thus for the strength of claims). A subsequent study, with a wider range of jurisdictions, found that smaller firms (fewer than 50 employees) are more likely to lose cases than larger firms [6]. Whereas the informality of employment relations is generally a strength of smaller firms, they may accordingly be less procedurally compliant and have weaker record-keeping, making them more vulnerable to successful legal challenges when problems arise.

As well as confirming the importance of firms’ adherence to legal requirements, a more recent UK study finds evidence that judges also take account of wider social and economic factors in their decision making [11]. Using the same data as another study [10], and accounting for case quality (proxied by the firm’s settlement offer) and selection bias by testing that case quality does not vary with local economic conditions, the study finds that factors such as unemployment and bankruptcy rates exert statistically significant effects on decisions. These effects are not small: on average, an increase of one percentage point in the unemployment rate is associated with a reduction of seven percentage points in the probability that a claim is decided in the employee’s favor, consistent with the notion of leniency toward employers in less favorable economic conditions. However, this effect is absent for unemployed claimants, suggesting that judges take account of the costs of dismissal in determining both remedy and liability.

To date, only a few studies have examined the role of economic factors in employment tribunal decision making. But their importance is becoming established as an empirical regularity, albeit the results are sometimes contradictory. For example, studies for both Italy and Spain, using different methods and levels of aggregation, find that judgments in favor of employees are countercyclical, in contrast to the findings noted in a study for Great Britain [12]. Some recent studies also consider other departures from pure legal decision making models, with evidence in Spain, for example, of spillover effects from judges in neighboring courts, arising from compliance with group norms (“peer emulation” effects) or fear of reversals on appeal [12]. These are interesting directions for research, especially given the shift in Great Britain toward judges sitting in tribunals without lay members in various claim types, including unfair dismissal cases.

Post-application consequences

While much of the policy interest has focused on costs of dispute settlement to employers, legislators also need to consider possible consequences for claimants, such as stigmatization. The only quantitative study to date on the consequences for claimants focuses on claimants displaced or made redundant at a time of tightening labor markets (2003), again using Survey of Employment Tribunal Applications data [13]. Consistent with the wider job displacement literature, the study finds that outcomes are generally worse for already disadvantaged labor market groups: women, older workers, ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, and managerial and professional workers, who take longer than other occupational groups to find another job, and when they do, the job is less likely to involve higher pay or status.

Critically, the probability of finding new employment is lowest and the length of time without work is longest for claimants with weak cases that are dismissed without a full hearing compared with other means of resolution (case withdrawn, settled, or decided at hearing). In addition to the benefits of managing the expectations of parties to the dispute and supporting conciliation, this highlights the need to ensure the availability of high-quality advice and conciliation, which assist parties in assessing the strength of their case [13]. Even so, the evidence suggests that employment tribunal cases seem to have little impact on employment prospects beyond the initial job loss, at least in tight labor markets.

Limitations and gaps

While this article describes the best evidence to date, there are important caveats. The available data largely preclude accounting for the bias that arises when, at various stages of disputes, samples of observed cases are subject to strategic selection. This is an important shortcoming even though studies that consider the issue find treating stages of dispute settlement independently does not greatly distort the results. Better dispute-tracking records are needed, as is more evidence on the behaviors that drive responses to problems at work, specifically those that infringe employment rights and may therefore result in tribunal claims. Ideally, these issues could be explored using longitudinal matched data on the parties, organizations, and internal dispute resolution processes.

Several other gaps in studies limit the ability of the findings to inform policy. Few studies have involved control groups to assess what would have happened in the absence of the intervention (the counterfactual), let alone used random assignment to intervention and control groups, which is needed for defining causal relationships. Multiple reforms enacted in close succession (in Great Britain at least) have also made disentangling the impact of individual measures challenging. Likewise, the periodic nature of surveys and their timing may limit how well they capture the impact of specific policy interventions.

Finally, it is worth noting that while several studies draw on models developed in other contexts—most notably the economics of civil litigation—this remains an under-theorized area.

Summary and policy advice

Understanding employment conflict and its resolution in employment tribunals and other labor courts is important in balancing employment protections with economic efficiency. Advances in understanding can potentially be made by learning more about claim instigation, conciliation, and adjudicator decisions. Having this information could reduce the number of claims brought before labor tribunals. Two approaches seem particularly promising.

First, although the factors driving claim instigation remain at best only partly understood, the evidence suggests that strengthening the representation functions of unions may moderate the number of claims. In addition, small firms account for a disproportionate number of claims, so supporting them in complying with labor laws and procedures and in seeking early resolution should be a priority—for example, training owner-managers in dispute resolution skills and in understanding how tribunals interpret and apply notions of formal process and fairness [6].

Second, potential litigants’ expectations about likely tribunal outcomes are key to the resolution of claims before they reach the tribunal. A policy recommendation that follows from this finding is to ensure that parties to a dispute have access to good information and advice. The Australian approach—providing extensive online, telephone, and other resources to assist increasingly self-represented litigants—is interesting. This goal might also be advanced by providing insights into judges’ decisions and outcomes, for example, through early neutral judicial evaluation to help in managing expectations. Practitioner groups have also suggested dealing with simpler, “technical” cases (such as unpaid wages) on paper without hearings, and dealing with more complex cases through a more inquisitorial (rather than adversarial) approach, as has recently been done in Ireland.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Paul Latreille