Elevator pitch

Raising the minimum wage in developing countries could increase or decrease poverty, depending on labor market characteristics. Minimum wages target formal sector workers—a minority in most developing countries—many of whom do not live in poor households. Whether raising minimum wages reduces poverty depends not only on whether formal sector workers lose jobs as a result, but also on whether low-wage workers live in poor households, how widely minimum wages are enforced, how minimum wages affect informal workers, and whether social safety nets are in place.

Key findings

Pros

If job losses in the formal sector are small, raising the minimum wage is likely to reduce poverty.

If informal sector wages rise when the minimum wage increases, higher minimum wages are likely to reduce poverty.

If the people earning the minimum wage are heads of low-income households, higher minimum wages are likely to reduce poverty.

If low-income workers lose jobs and cannot find jobs because of a higher minimum wage, social safety nets for low-income households can protect against increased poverty.

Cons

If higher minimum wages cause workers to lose formal sector jobs, they are not likely to reduce poverty.

If minimum wage legislation does not cover a large pool of informal workers, higher minimum wages are not likely to reduce poverty.

If the workers affected by the minimum wage are secondary family workers, higher minimum wages will not reduce poverty.

If low-income workers lose jobs and cannot find new ones because of higher minimum wages and there are no social safety nets, higher minimum wages will increase poverty.

Author's main message

Raising the minimum wage reduces poverty in most developing countries. But the impact is modest because the minimum wage applies to only a minority of poor workers; in particular, it does not cover workers in the large informal sectors. And raising the minimum wage creates losers as well as winners among poor households—depending on employment effects, the wage distribution, and effects on the household head—pulling some out of poverty while pushing others in. Raising the minimum wage could be part of a comprehensive poverty-reduction package but should not be the only, or even the main, tool to reduce poverty.

Motivation

A popular and compelling argument in favor of raising legal minimum wages is that higher minimum wages will reduce poverty. Quite simply: putting more money into the pockets of low-income workers will allow them to purchase more of the basic goods and services needed to survive. In theory, if the wage increase is large enough, poor people’s incomes will rise, lifting them out of poverty.

This sounds good in theory—but it does not always happen in practice. That is because the relationships between minimum wages, worker incomes, and employment levels, and the incidence and depth of poverty are complex.

First, the minimum wage does not affect all workers or affect them equally. That makes it important to know which workers are most likely to be affected—and how. Second, even if a minimum wage raises the incomes of some workers, it might not raise the incomes of poor households. The informal sector, where workers are not effectively covered by minimum wage legislation, is typically large in developing countries, and poverty tends to be more widespread in the informal sector. Even in the formal sector, minimum wage laws are often poorly enforced.

There are also employment effects to consider. An increase in the minimum wage may cause some employers to lay off workers. If these workers live in low-income households, poverty may increase, at least in the short term. Layoffs in the formal sector may also put downward pressure on wages in the informal sector by increasing competition for informal jobs.

For all these reasons, increasing the minimum wage might have no positive impact on poverty—or worse, might backfire and deepen poverty, especially for the extremely poor.

Discussion of pros and cons

Impacts on wages and employment in the formal sector

Minimum wage increases most directly affect earnings and employment in the formal sector. Higher minimum wages lead to higher wages for formal sector workers who keep their jobs. Studies for developing countries suggest that the positive wage effect is strongest for workers earning near the minimum wage. As a result, increases in the minimum wage tend to compress the wage distribution (equalize wages) in the formal sector.

However, increases in the minimum wage might not help formal sector workers most in need as some workers affected by the minimum wage increase already earn above the minimum wage. In Latin America the minimum wage is often used as a guide by employers in setting all wages, even those well above the minimum wage [2].

In addition, minimum wages might affect the wages of high-wage workers because some countries have multiple minimum wages. In Costa Rica, where wages are set by occupation and skill, a university graduate being paid the minimum wage for that category of worker would be in the top 10% of the wage distribution [3]. In Kenya, Namibia, Tanzania, and South Africa, where more than half of employees earn less than the lowest minimum wage, the highest minimum wages reach well into the upper half of the wage distribution [4].

All these effects are for workers who retain their jobs. What about employment? The evidence is mixed. The majority of studies conclude that increasing the minimum wage reduces formal employment, although the effect appears to be small in most countries. Almost all estimates suggest that a 1% increase in the minimum wage results in less than a 1% decrease in employment, implying that the total earnings of formal sector workers increase when minimum wages rise.

Impacts on wages and employment in the informal sector

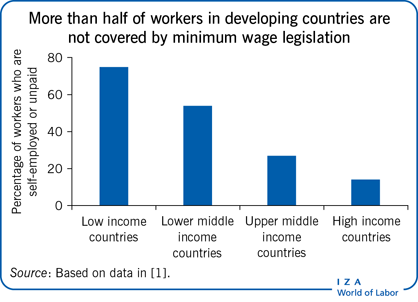

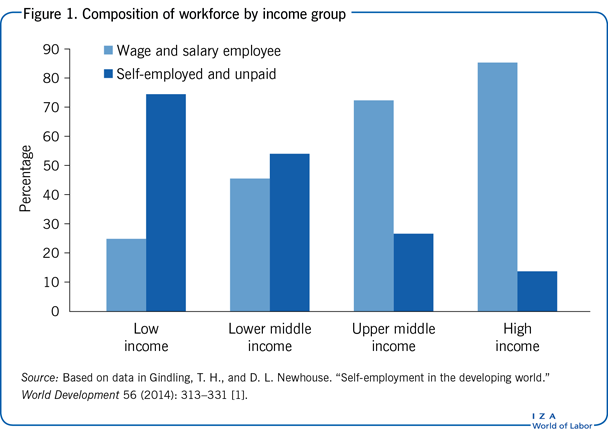

The impact of the minimum wage on wages and employment—and poverty—also depends on what happens in the informal sector. More than half of workers in low- and lower-middle-income countries work in this sector, which is not covered by minimum wage legislation (Figure 1). This complicates the picture. A large informal sector can cushion the effect on poverty of a higher minimum wage if workers who lose jobs or who cannot find formal sector jobs as a result of the increase find work in the informal sector—even low wages may be better than no wages. But the effect could be just the opposite for some workers. Higher minimum wages might force more workers out of the formal sector and into the informal sector, and the lower wages could push their households below the poverty line.

In some countries, higher minimum wages have resulted in higher wages for workers in both the formal and informal sectors (some researchers call this the “lighthouse effect”) [2]. In other countries, higher minimum wages seem to have little or no impact on wages in the informal sector [5]. Still other studies find that a higher minimum wage depresses wages for informal sector workers [6].

Taken together, the evidence for developing countries suggests that a higher minimum wage generally leads to an increase in total earnings for workers as a group. However, the evidence also suggests that a higher minimum wage creates both winners and losers. Some workers see their earnings increase, while others see their earnings fall because they become unemployed, leave the labor force, or are forced into lower-paid jobs in the informal sector.

How do these wage and employment dynamics in the formal and informal sectors affect poverty? It is not possible to know based on aggregate wage and employment data alone. The key issue is how households are affected by the minimum wage. Even if raising the minimum wage increases total earnings for workers, higher minimum wages could still increase poverty if the benefits go to workers who are not poor and the costs are paid by workers who are.

Impacts can vary along the wage distribution

Understanding the impact of minimum wages on poverty requires understanding their impact at different points in the wage distribution. For policymakers, that issue can affect how the minimum wage is set and with what wage group in mind.

For example, when minimum wages are low relative to average wages (as in Brazil, China, and Mexico), they tend to raise the wages of workers at the bottom of the wage distribution [2], [7]. But when minimum wages are high relative to average wages (as in Colombia, Honduras, and sub-Saharan Africa), they will increase the wages of workers in the middle but not at the bottom of the wage distribution. In this case, higher minimum wages will only affect those whose wages are high relative to average wages (since those earning less than the minimum wage are not directly affected by minimum wages).

While the benefits of higher minimum wages are distributed across the wage and skill distributions, studies in developing countries suggest that employment losses tend to be concentrated among workers with characteristics associated with low wages. Overall, women, young workers, and less-educated workers, whose wages tend to be low, suffer the heaviest employment losses [2]. In Brazil, Colombia, and Costa Rica, employment losses were largest at the bottom of the distribution of wages and skills, though there were sometimes smaller employment losses even for workers earning well above the minimum wage.

Do workers affected by minimum wages live in poor households?

Accounting for the wage distribution can increase understanding of how minimum wages might affect poverty. But it is still necessary to know the household income of workers at different wage levels, because poverty is defined in terms of household income, not individual earnings.

For example, a worker in the upper half of the wage distribution might live in a poor household, so a higher minimum wage could help that worker’s household escape poverty. Or a worker at the bottom of the wage distribution could be a secondary wage earner in a nonpoor household, so a higher minimum wage would make this household better off but would not reduce poverty.

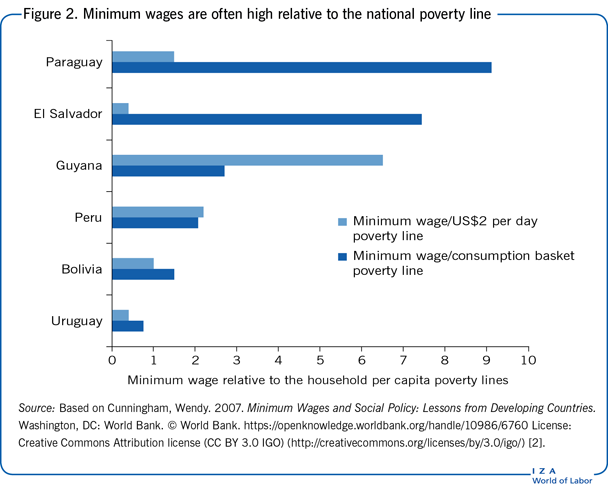

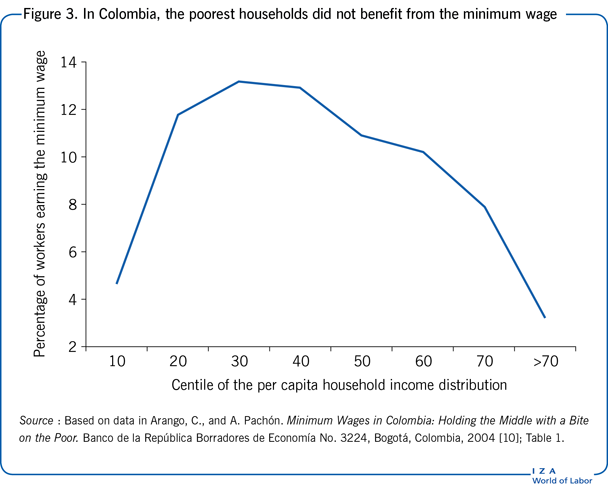

The impact of higher minimum wages on poverty also depends on whether the concern is solely with the number of households with incomes below the poverty line (the incidence of poverty) or also with how far the poor are below the poverty line (the poverty gap). In the second case, it will matter which poor households benefit and which poor households lose when minimum wages rise. Raising the minimum wage could raise the incomes of some poor households with incomes near the poverty line while reducing the incomes of the poorest households at the bottom of the distribution (Figure 2).

Studies using aggregate country-level data to examine the correlations between minimum wages and poverty have generally found that in developing countries higher minimum wages are correlated with lower poverty rates [8]. The results of studies that use individual- or household-level data to examine the impact of higher minimum wages across the household income distribution are mixed. The findings suggest that in most developing countries higher minimum wages modestly reduce poverty rates, although the results depend on the country studied:

In Thailand, higher minimum wages have the largest positive effect on households at the lower end of the household income distribution. In this case, minimum wages have a relatively large impact on poverty; a 10% increase in minimum wages reduces poverty by 2.5 percentage points [9].

In Mexico, workers in the poorest households had the largest wage gains following an increase in the minimum wage (reducing the poverty gap), but the wage gains were not large enough to pull most of these households above the poverty line [2].

In Colombia, workers earning the minimum wage were most likely to be in households in the middle of the income distribution (Figure 3); the poorest households did not benefit from minimum wages [10].

Likewise, in Brazil, higher minimum wages did not raise the incomes of households in the bottom three deciles of the household income distribution [11].

In Honduras, with a large informal sector and where almost half of formal sector workers earn below the minimum wage, a higher minimum wage led to an increase in extreme poverty along with small increases in incomes for formal sector workers near the poverty line [6].

This suggests that higher minimum wages in Colombia, Brazil, and Honduras did lead to moderate declines in poverty for some households, but did not reduce poverty among the very poorest households. In other words, minimum wages modestly reduced the incidence of poverty but increased the gap between the average incomes of the poorest households and the poverty line.

Impacts may differ between household members

The impact of minimum wages on household incomes also depends on how many household members are working and how each worker is affected by minimum wages.

For example, higher minimum wages will not affect the incomes of households in which no one is working. In contrast, in low-income households with more than one worker, raising the minimum wage could increase the earnings of one household member and reduce the earnings of another. If the workers earning the minimum wage are secondary workers in households whose total income is well above the poverty line, a higher minimum wage will have little or no impact on poverty. But it is also possible that a higher minimum wage could induce secondary family workers in poor households to work more, boosting household incomes.

Whether minimum wages are more likely to affect household heads or secondary family workers is particularly important. Results from studies in Brazil, China, Colombia, and Nicaragua suggest that if a higher minimum wage increases the wages of household heads without leading to large employment losses, poverty will fall (this will happen even if secondary workers lose work). On the other hand, if minimum wages have a significant negative employment effect on household heads, then higher minimum wages will have, at their best, only modest impacts on poverty (this will happen even if there are positive employment effects on secondary family workers).

In Colombia, higher minimum wages had a significant negative effect on the employment and hours worked of household heads, but not on the employment and hours worked of secondary workers [10]. In Brazil, higher minimum wages also reduced the employment of household heads and increased labor force participation slightly for other household members [11]. As noted, higher minimum wages in Colombia and Brazil had a modest impact on poverty and no impact on the incomes of the poorest households.

But in Nicaragua the reverse holds: household heads were less likely than other members to lose their jobs because of higher minimum wages [5]. Moreover, household heads who lost their jobs because of higher minimum wages were more likely to find work in the public sector, which is not affected by minimum wages, or as self-employed workers, while other household members who lost their jobs were more likely to leave the labor force. As a result, higher minimum wages caused a statistically significant and substantial reduction in poverty in Nicaragua.

In urban China, where minimum wages are low relative to median wages and compliance with minimum wages is high, an increase in the minimum wage pulls more people out of poverty than it pushes in, leading to a modest decrease in overall poverty. The reduction in poverty is greatest if the minimum wage increase applies to a female household head [12].

In summary, if minimum wages have a positive wage effect but a small negative employment effect on household heads, then higher minimum wages are more likely to reduce poverty (even if there are significantly negative employment effects on non-household heads). On the other hand, if minimum wages have a significantly negative employment effect on household heads, then higher minimum wages are less likely to reduce poverty (even if there are positive employment effects on secondary family workers).

Impacts of higher minimum wages on nonlabor income

Minimum wages can also affect other sources of income received by poor households. For example, social safety net programs can soften the negative impacts of higher minimum wages on poor households by supplementing incomes when a household member loses a job.

Several Latin American countries tie many of the social benefits for low-income households to the minimum wage [2]. In Brazil, for example, where noncontributory pensions make up a large portion of the income of many poor households and their value is tied to the minimum wage, higher minimum wages substantially lowered poverty between 1994 and 2004. The higher minimum wages were responsible for 32% of the unprecedented reduction in income inequality in Brazil in the 1990s and 2000s because of their impact on nonwage income [13].

One danger of tying social safety net payments or eligibility to the minimum wage is that higher minimum wages may strain government budgets, forcing curtailments of public spending on other important government priorities.

In addition, the minimum wage is generally not a good proxy for the subsistence needs of households; for half the countries in Latin America, it is insufficient to provide for household needs. The best practice is usually to anchor social assistance to a given consumption bundle or to economywide average earnings [2].

Income transfers between households may also be important. In South Africa and some other developing countries, income is shared among households to ease the impact of a negative shock. A higher degree of income sharing between the employed and unemployed reduces the probability that a higher minimum wage will push a household into poverty.

Limitations and gaps

The research on the wage and employment impacts of minimum wages in developing countries is voluminous, but most of it concerns Latin American countries; other regions have been studied much less. And, even in Latin America, there is little research on other factors that affect the relationship between minimum wages and poverty. Among the most important information gaps in most countries is how and why raising the minimum wage affects household members in different ways—and whether the impacts differ in poor and nonpoor households.

For most countries, it would be useful to determine whether workers who earn the minimum wage are likely to live in poor households and whether they are likely to be household heads or secondary family workers. More difficult, but also quite important, would be to estimate the positive wage effects and negative employment impacts of minimum wages separately for different household members, especially for household heads and secondary workers and for households in different parts of the income distribution.

Summary and policy advice

Most empirical studies of the impact of minimum wages on poverty in developing countries conclude that increases in minimum wages reduce poverty, on balance, though they find only a modest impact—for two reasons.

First, a large share of workers is not covered by minimum wage legislation.

And second, higher minimum wages do not affect all low-income households the same way: minimum wages pull some households out of poverty, but may push others into poverty.

Given the potential for negative impacts on the employment status and incomes of some of the poorest families, raising current minimum wages is an inefficient tool for reducing poverty. More efficient policies would focus on

enhancing compliance with minimum wage laws,

improving incomes in the informal sector where minimum wages do not apply,

increasing the long-term productivity of workers from low-income families, and

enhancing social safety nets for workers who lose jobs when minimum wages increase.

This suggests that while minimum wages can be part of a package of poverty-reducing policies, they should not be the only mechanism or even the most important one.

For example, Brazil’s conditional cash transfer program, Bolsa Familia, was more effective than higher minimum wages at reducing poverty and income inequality using an identical amount of resources [13]. Conditional cash transfers to low-income households have the additional benefit of providing part of a social safety net for households when workers lose their jobs because of higher minimum wages. Incentives for firms to increase labor demand, such as employment subsidies, can lead to positive employment and earnings effects. Labor supply incentives, particularly the earned income tax credit, have also been shown to be effective in increasing both the employment and earnings of low-income workers in the US.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. The author would also like to thank Gary Fields and the other participants of the IZA World of Labor Minimum Wage Workshop, 2013. Version 2 of the article adds short discussions on sub-Saharan Africa (Kenya, Namibia, Tanzania, and South Africa), Thailand, Honduras, and China. Six new key references have been introduced [3], [4], [6], [7], [9], [12] and four from version 1 moved to the “Additional references” online.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© T. H. Gindling