Elevator pitch

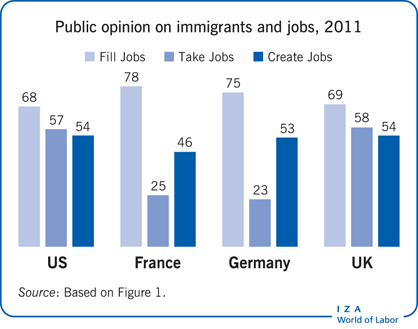

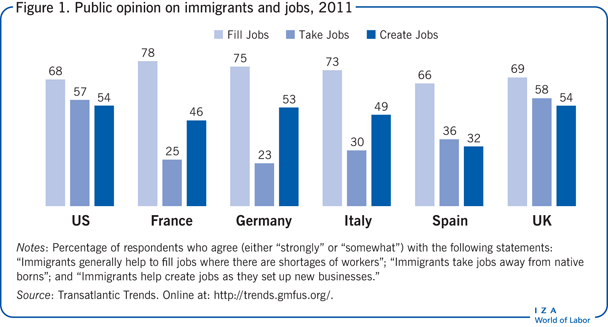

Neither public opinion nor evidence-based research supports the claim of some politicians and the media that immigrants take the jobs of native-born workers. Public opinion polls in six migrant-destination countries after the 2008–2009 recession show that most people believe that immigrants fill job vacancies and many believe that they create jobs and do not take jobs from native workers. This view is corroborated by evidence-based research showing that immigrants—of all skill levels—do not significantly affect native employment in the short term and boost employment in the long term.

Key findings

Pros

Immigrants who are self-employed or entrepreneurs directly create new jobs.

Immigrant innovators create jobs indirectly within a firm, leading to long-term job growth.

New immigrants fill labor shortages and keep markets working efficiently.

High-skilled immigrants contribute to technological adaptation and low-skilled immigrants to occupational mobility, specialization, and human capital creation; both create new jobs for native workers.

By raising demand, immigrants cause firms and production to expand, resulting in new hiring.

Cons

Low-skilled immigrants may compete in the short term, but the effect is small and not statistically significant.

If low-skilled immigrant workers only supplement the work of high-skilled native workers, they may be trapped in low-skill, low-paying jobs.

If low-skilled immigrant labor is employed in lieu of physical capital, technological advances and capital upgrading are impeded.

A country that becomes dependent on low-cost immigrant workers may have to outsource jobs when these workers are not available.

Immigrants may increase production without boosting productivity.

Author's main message

Immigration’s positive effects far outweigh any negative impact. Migrants choose locations with available jobs and fill labor shortages. Whether high- or low-skilled, migrants rarely substitute directly for native workers. Instead, migrants often complement native workers or accept jobs that natives don’t want or can’t do. They create new jobs by increasing production, engaging in self-employment, and easing upward job mobility for native workers. The presence of immigrants increases demand and can spur new businesses to open, creating more jobs for immigrant and native populations.

Motivation

Job loss is a core topic of heated public debates on immigration, but much of the public discourse is uninformed by the evidence (Figure 1). If policymakers are to draft immigration measures that are context-specific, broadly advantageous, and acceptable to native and immigrant populations, common misconceptions about immigration must first be exposed. Educated answers to two core questions can provide sound information for decision-making: Do native workers really fear that immigrants will take their jobs? If so, is such fear backed up by scientific studies? In both cases, the answer is no.

Discussion of pros and cons

A brief discussion of the economic theory of migration’s impact on jobs helps put the issue in perspective. It is important to understand possible adjustment mechanisms that can be triggered by migration related to labor supply changes, such as the mobility or displacement of native workers, professional upgrading, and firm adaptation. Key concepts include skill distinction, competition versus complementarity, and job protection.

The simple labor market model

The traditional labor market model, with employers on the demand side and employees on the supply side, defines the equilibrium wage and employment at the intersection of demand and supply. Employers hire all the workers they need at this wage, and all employees who want to work at this wage can find a job. Immigration increases labor supply. In the short term, holding all else constant (such as the demand for labor and international trade), the increase in labor supply lowers the equilibrium wage and raises the equilibrium level of employment, but it is not clear who gains from the increase in employment. It is possible that some native workers lose their jobs or drop out of the market and that some immigrants find jobs while others remain unemployed. The outcome hinges on stringent assumptions, such as full employment, no labor market segmentation, identical skills for immigrants and native workers, and immediate access by immigrants to all jobs held by native workers. In this short-term model, immigrants are considered perfect substitutes for native workers, and they affect the labor supply curve as if natives have replicated themselves.

The pragmatic labor market model and job creation mechanisms

In real life, native workers and immigrants differ in their country-specific human capital, such as language fluency, professional networks, and social and cultural knowledge. Initial skill differences make new immigrants and native workers imperfect substitutes. In addition, labor shortages and job vacancies are more common than full employment.

Labor, capital, technology, and resources are all production inputs that can complement or substitute for one another. According to economic theory, immigrants—as one of the inputs in production—raise the price of inputs they complement and lower the price of inputs for which they are perfect substitutes.

The economics of migration tell us that a country needs immigrants because its native labor force is not large enough to meet demand or specialized enough to handle technological changes. Vacancies exist even under high unemployment because native workers and jobs do not always match or because unemployed workers might not want or be qualified for the jobs available. Native workers often shun low-skill, repetitive jobs, preferring to stay unemployed, especially in countries with a strong welfare state system. Employers may then try to fill jobs by bringing in low-skilled immigrants—or by outsourcing. While the skills required for the job might be below immigrants’ capabilities, immigrants are willing to accept the jobs in order to move to a country offering higher wages than their home country. Immigrants also tend to have tight ethnic networks which help them locate where the jobs are.

At higher skill levels, there are also some jobs for which the native labor force might not yet be qualified; native workers cannot instantaneously adapt to all the high-skilled jobs that emerge from rapid technological advances. Hiring qualified immigrant workers is a reasonable short-term solution because they can complement the work of native workers.

High-skilled workers are by definition specialists. Because of their unique skills, they are less substitutable, command high wages, and complement capital and technology. High-skilled immigrants can collaborate with high-skilled native workers (for example, university professors, information technology experts, and dancers) and encourage further specialization. And they can work well with low-skilled workers, whether foreign- or native-born, whose skills they complement. The resulting synergies can lead to job creation, and the economy can accommodate many more workers as the low-skilled help the high-skilled specialize and climb the socio-economic ladder. As long as labor markets can adapt to the supply of immigrant workers, skill variety and balance can create more efficient production processes.

The factors held constant in the theoretical short-term model can change in the long-term so that labor markets can accommodate migrant workers without harming native workers. New firms may spring up to take advantage of the low-wage, readily available supply of immigrant workers. Existing firms may adjust their investments and physical capital to take advantage of the skills available, so the increased supply of immigrant labor does not simply shift the supply curve. As a result of these two mechanisms, firm profits rise, further increasing the demand for low-wage workers and driving up wages and employment. The country may open up more to international trade. And the economy may become more flexible in producing a differentiated output mix and adjusting to the new skill combinations.

Another reason why immigrants do not simply displace native workers is that, as new arrivals, they do not have access to the same jobs as native workers. In segmented labor markets, immigrants may be slotted for a long time into lower tier jobs as supplements to native workers. Although this benefits native workers, it can trap immigrants at low socio-economic levels. In addition, immigrants who are self-employed and entrepreneurs may directly create jobs, for themselves and for any native workers they might hire. As entrepreneurs and innovators, immigrants can provide more jobs indirectly, through research and development within their firms.

The demand for goods and services cannot remain static. Immigrants affect the labor supply as workers and increase the demand for goods and services as consumers. Higher demand affects the labor market by boosting demand for labor, leading to an increase in equilibrium employment. And immigrant workers, especially the higher skilled, pay more in taxes than they receive in government benefits.

Competition and negative job effects

There will always be some competition between immigrant and native workers with the same skills. Labor market flexibility determines how much.

The research on the impact of immigrant workers on native workers takes two approaches: an area approach or a production function approach. The area approach, or spatial correlations approach, compares economic outcomes for native workers in areas with large immigrant inflows and those with low inflows. Most studies have found no adverse effects of large immigrant inflows. Some caution is required, however, since simple spatial statistics might lead to the wrong conclusions. For example, in 1994 in Miami, the rise in black unemployment that coincided with the expected arrival of Cuban immigrants might have been blamed on immigration even though the immigrants never arrived because their ship was intercepted at sea on orders from the US president. Spatial studies might also understate the actual impact of immigration in a locality if there are flaws in the econometric models or their estimation. The second method uses national data and differentiates workers by skills using a production function [1]. These studies find a moderate degree of competition among low-skilled workers and a negative impact on native workers. However, more methodologically complex studies focusing on the degree of substitutability among workers and the effects on employment and wages of substitutable and nonsubstitutable workers find no negative effects.

A study in the late 1990s of the displacement effects of immigrant workers on native workers in Canada found mixed effects according to the origins and occupations of the immigrants [2]. US immigrants, who had similar skills and competed with Canadians in many fields, had significant negative effects on Canadian workers. European immigrants, who complemented Canadian workers in most fields and competed with them in a few, had negative effects only where they competed with Canadian workers. And developing country immigrants had negative effects on Canadian workers only in the few occupations in which they competed with rather than complemented them. There is some evidence from 2012 that suggests part of the decline in youth employment for the US was related to increased competition from substitutable immigrant workers in low-skill jobs.

Low-skilled workers, who can perform repetitive, manual tasks at a lower cost than it takes to upgrade equipment, are often substitutes for capital. From this angle, employers may view all low-skilled workers as close substitutes. Thus, immigrant and native workers with low skills may compete directly for jobs, at least in the short term. Most studies agree that this has occurred in some markets and areas. However, the negative employment effect is small and not statistically significant. More often, the negative effects arise in the case of competition between recent and earlier immigrants, who have very similar skills.

When low-skilled immigrant workers are hired alongside high-skilled native workers it frees native workers to specialize, invest in education and training, and upgrade their occupations. The jobs they vacate are then available for others to fill, whether immigrant or native workers. But this complementarity and the ensuing upward mobility of native workers may consign generations of immigrant workers to low-skill, low-paying employment, especially in hierarchically structured labor markets. By reinforcing perceptions that some occupations are “immigrant jobs” and solidifying stereotypes, this pattern of employment and mobility reduces social cohesion and integration and may prevent immigrants from investing in education and entering higher-skilled occupations.

Over time, immigrants adjust to the culture of their new home and invest in learning fresh skills, which might put them in competition with native workers. There is not enough evidence, however, to sustain this claim, mostly because immigrants operate in different jobs, sectors, and industries than native workers. And even if immigrants have been in a country for a long time—and have mastered the same skills as native workers—they still differ from native workers and work in different jobs.

Repeatedly hiring workers from abroad into low-skill, low-paying jobs can create two negative effects: dependency on low-paid foreign workers and neglect of capital and technology upgrading. Most agricultural or seasonal jobs exhibit these effects. While filling these jobs with immigrant workers does not directly affect native workers’ jobs, there are wider ramifications, such as difficulty enforcing the return home of seasonal workers, some of whom may stay in the US and go underground as undocumented workers. Failing to upgrade capital or use new technology could mean that these jobs and outputs would become uncompetitive, eventually moving abroad.

Immigrants are more likely than native workers to start a business and create their own jobs. However, while immigrants may take business start-up opportunities away from native workers, they do not put native workers out of business because immigrants operate in different ethnic niches.

Immigrant workers may contribute to growth in the production of goods and services, but productivity may not always grow along with it. For high-skilled Russian émigrés to Israel in the 1990s, the immigrant share in production was positively correlated with productivity in high-tech industries but strongly negatively correlated in low-tech industries [3]. The positive correlation in high-tech industries reflects complementarities between technology and the skilled immigrant workforce.

Jobs can be differentiated by sector as well as skill. If many low-skilled immigrant workers enter a specific sector—for example, construction—they will compete with low-skilled native workers in that sector. For example, when the share of immigrant workers rose in some blue-collar fields in France, some native French workers moved away from these sectors. Some of them went into less repetitive occupations in the same area, and some moved to other areas. The native workers who stayed in the high-immigration areas were able to upgrade their occupations when immigrants moved into their former, low-skill jobs. The native workers who moved to other areas had lower average earnings than the native workers who stayed in the area and changed jobs.

Some argue for the need for strong employment protection laws to shield native workers against job losses to immigrant workers. While such legislation can reduce job loss in the short term, it may exacerbate the negative impact in the long term by slowing or preventing the movement of native workers into higher skilled, better paying jobs.

Immigration’s positive contributions to labor markets

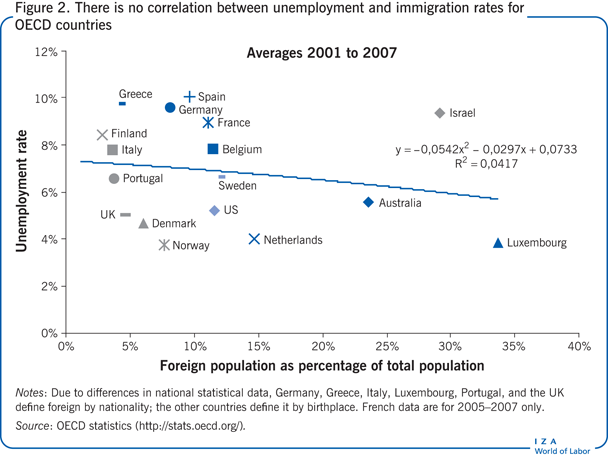

Studies find no correlation between unemployment and the share of immigrants in a country. Indeed, a study of the effect of increased immigration in Europe in 1991 found that in competitive markets, labor migration increased the efficiency and flexibility of labor markets and slowed wage growth, allowing more people to find jobs [4]. Data from 2001–2007 for 17 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries show similar results: there is no correlation between unemployment and immigration rates (Figure 2).

Empirical studies that took advantage of natural experiments to study the effects of increased immigration found no adverse effects on native workers. A study of the arrival of 125,000 Cuban immigrants in Miami between May and September 1980—a 7% increase in the labor force—found no negative effects on native Floridians but some negative effects on earlier Cuban immigrants [5]. Although it is possible that Miami was particularly successful at absorbing immigrants, other studies have also found that other US cities with high shares of immigrants were able to absorb low-skilled immigrants within industries by adapting production technologies to the new local labor supply. There was no evidence that immigration harmed employment opportunities for low-skilled native workers.

In the 1940s, the US Bracero Program recruited unskilled Mexican laborers to fill agricultural jobs that were not being filled locally. This short-term, demand-driven immigration enabled farmers to meet growing demand for affordable agricultural goods. The braceros did not take jobs away from Americans, but their low cost and substitutability with capital postponed technological upgrading and increased employer profits.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Germany recruited unskilled guestworkers to fill labor shortages (by 1972, the proportion of guestworkers in the construction sector was 17.8%). No displacement of native workers has been recorded; rather, immigrants expedited the upward mobility of German workers due to their complementarity in the production process, contributing to Germany’s “economic miracle” (Wirtschaftswunder). The immigrants fared less well, however, operating under less favorable labor market structures than German workers, making it harder for them than for native Germans to translate their human capital into a good first job. In the 1990s, during another influx of immigrant labor to Germany, there were again no adverse effects on native workers because there was no substitutability between them, but earlier migrants suffered some adverse employment and wage effects. Had the German labor market been less segmented and more flexible, it would have been even more efficient in dealing with the effects of increasing immigration [6].

Similar effects occurred in other countries. In northern Italy in the mid-1990s, immigrants filled many manual labor-intensive jobs that had gone unfilled, enabling factories to expand, rather than shrink and fail, which would have left many native workers unemployed. Similarly, in Greece in the early 2000s, low-skilled, low-cost immigrant workers helped some industries withstand competition from low-labor-cost countries, preserving the jobs of native workers. And in Austria in the early 2000s, segmentation of the labor market prevented rising unemployment among native workers as more immigrants were hired.

Immigration can affect native workers at the household production level as well. For example, in Italy, low-skilled immigrant women provided household services that enabled high-skilled native women to spend more time at work.

Immigrants with advanced degrees from US universities working in science, technology, engineering, and math dramatically boost the employment of native workers. And immigrants with advanced degrees are more likely to start successful companies than are native workers with similar education. These immigrant entrepreneurs, far from taking jobs from native workers, create jobs for them as well as for themselves [7]. In the US during 1996–2004, 0.46% of immigrants created new businesses compared with 0.35% of native workers. And immigrant workers in the US have a higher innovation rate than native workers, patenting at double their rate. As these patents turn into marketable products and services, they create new jobs.

When immigrants are clustered in routine, labor-intensive jobs, native workers are able to specialize and upgrade their own skills. In Europe, immigration over 1996–2007 is associated with job creation and employment upgrading into higher-skill, better paying jobs for native workers. Employment creation was significantly larger in countries with more flexible labor laws [8]. More immigrant labor was also associated with higher self-employment among native European workers [9]. In Denmark, the hiring of low-skilled, non-European immigrants resulted in a reallocation of occupations across firms and municipalities as native workers pursued more complex occupations.

In Europe and the US, immigration has a strong positive association with productivity growth, because immigrants specialize in manual-intensive tasks and native workers in communication-intensive tasks. Immigration has a positive net effect on productivity and employment of native workers, unlike the offshoring of jobs. Immigration reduces the share of offshored jobs rather than the share of native workers’ jobs [10]. In the enlarged European Union (EU15), the free movement of workers improved the allocation of skills and boosted productivity. The receiving labor markets were able to absorb migrants from new EU members without any significant negative effects on employment levels.

Limitations and gaps

It is difficult to accurately measure the employment impacts of immigrant workers on native workers because of the absence of a direct measure of the counterfactual—what would have happened had there been less migration. Natural experiments and quasi-experimental research have been able to fill part of that analytical gap.

Data accuracy is another problem, particularly for employment classification, self-reported wages (such as in national censuses), and foreign experience and education. Simple stratifications, such as number of years of formal education, do not adequately define skill levels. Job categories are imperfectly transferable across countries, so professional experience is also not easily quantifiable.

Studies usually choose to evaluate either legal or unauthorized migrants. It is difficult to gather accurate information on unauthorized immigrants. To overcome this problem, some research has focused on periods after unauthorized immigrants have been granted amnesty.

Future research should continue to concentrate on immigrant cohorts’ skill and education levels and on native workers’ occupational specializations in response to rising migrant employment, particularly in the long term. To deepen understanding of labor market reactions to immigration, research should include impacts in developing countries.

Summary and policy advice

The evidence does not support policy intervention to “protect” native employment. Instead, the quantitative evidence shows that, overall, immigrants do not take native workers’ jobs in the long term and that they stimulate job creation through increased production, self-employment, entrepreneurship, and innovation. They also provide opportunities for native workers to upgrade their occupation and specialize in higher-skill jobs. Any short-term negative effects on native employment are small and insignificant. For the most part, these findings align with public opinion in developed countries. In the worst case, the only workers whose jobs are affected are those with strikingly similar skills and background—generally earlier immigrants. High-skilled immigrant workers complement physical capital and technology and the human capital of both low- and high-skilled native workers. This complementarity leads to greater and more efficient production and to economic growth, making all consumers and the national economy better off.

This mechanism functions naturally only when labor markets are flexible. Admitting immigrants with a mix of skills while maintaining flexible labor markets allows firms to adapt to the labor supply. Countries benefit from engaging rather than restricting immigrant workers.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts and Victoria Finn for excellent research assistance.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Amelie F. Constant