Elevator pitch

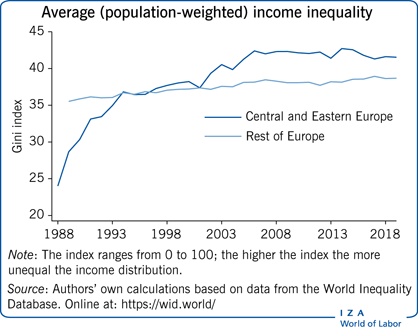

High levels of economic inequality may lead to lower economic growth and can have negative social and political impacts. Recent empirical research shows that income and wealth inequalities in Eastern Europe since the fall of socialism increased significantly more than previously suggested. Currently, the average Gini index (a common measure) of inequality in Eastern Europe is about 3 percentage points higher than in the rest of Europe. This rise in inequality was initially driven by privatization, liberalization, and deregulation reforms, and, more recently, has been amplified by technological change and globalization coupled with relatively ungenerous income and wealth redistribution policies.

Key findings

Pros

Income inequality grew radically in Eastern Europe during the transition to market economies.

The rise in inequality is significantly higher when fiscal data with better coverage of top incomes are used to measure inequality.

Major determinants of increased income inequality include market reforms, the rise of private capital, and relatively low levels of income redistribution.

Wealth inequality in some Eastern European countries is among the highest in Europe.

Cons

Income and wealth distribution data for Eastern Europe are imperfect and inequality estimates are very uncertain.

Household survey data suggest that income inequality in Eastern Europe is generally close to the EU average level.

Wealth inequality increased in all ex-communist countries, but on average it is lower than in other European countries.

Income redistribution in Eastern Europe seems to be slowly converging to Western European levels.

Author's main message

Income inequality in Eastern Europe has grown significantly more since the collapse of socialism than previously thought—as found in recent research supplementing household survey data with information from fiscal sources and national accounts. Currently, income inequality in ex-communist countries is, on average, higher than in the rest of Europe. Eastern European governments should thus enact reforms to increase income redistribution, such as more progressive income taxation and employment-conditional low-wage subsidies. Wealth or inheritance taxes should be considered in the Baltic countries as they are among the most wealth-unequal states in Europe.

Motivation

High or increasing economic (income and wealth) inequalities can lead to serious negative economic, social, and political consequences. Even though empirical research on the effects of inequality is plagued with imperfect data and methodological constraints, there is a significant body of evidence suggesting that inequality can have profound detrimental impacts on economic growth, individual happiness and health, political participation, and other outcomes. Recent studies have found that increasing income inequality may be responsible for growing worldwide dissatisfaction with democracy [1] and the rise of support for populism and illiberalism [2]. Research has also shown that income inequality is negatively associated with intergenerational mobility and equality of opportunity for income acquisition [3].

In this context, the experience of the post-socialist Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries is particularly worth studying. These countries had relatively equal income and wealth distributions under socialism, but witnessed an explosion of inequality during the process of transition to market economies. The trajectories of inequality growth in the CEE countries have been shaped by several economic and political processes, including the depth of their initial transition recession and growth performance during the transition period. Recent progress in constructing more comprehensive income and wealth distributions by relying on combined data from household surveys, tax sources, and national accounts statistics reveals that the magnitude of inequality rise in the CEE region has previously been severely underestimated. This article summarizes existing knowledge and exploits novel estimates of income and wealth inequality trends in the CEE countries to illuminate factors that were responsible for the expansion of inequalities in the region.

Discussion of pros and cons

Evolution of income inequality in the CEE countries

Household surveys have traditionally been the primary source of income data for measuring inequality. However, research from the last two decades documents convincingly that microdata from surveys suffers from important limitations. From the perspective of measuring inequality, the most important shortcomings are related to measurement error and the underrepresentation of top incomes. Many studies show that data for high-income-earning households appear to be less representative in surveys than data for households with incomes belonging to the middle or lower parts of the income distribution. Additionally, the top incomes available in surveys seem to be underestimated due to the incomplete response of high-income earners or unavailable due to so-called top-coding. Inequality estimates based on survey data may therefore be biased and underestimated. These findings have provided the impetus for constructing more comprehensive income distributions (distributional national accounts, DINA) that, in addition to survey data, also exploit data from income tax returns and national accounts to help overcome the deficiencies of survey-based estimations [4].

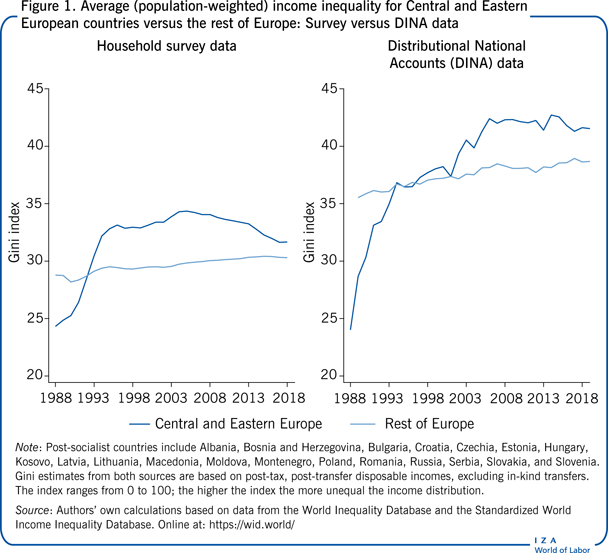

For many countries and regions, inequality levels and trends estimated from surveys can sharply diverge from those estimated using DINA. This is also the case for the CEE region, as shown in Figure 1. Both data sources show that income inequality under socialism in the late 1980s was much lower than the average income inequality in non-socialist European countries. The transition to market economies since the early 1990s is marked by a huge rise in income inequality as measured by the Gini coefficient. When measured using survey data, the inequality rise reaches 10 percentage points between 1988 and 2005; however, based on the DINA data it is as much as 17 percentage points over the same period. Both data sources indicate that in the mid-2000s income inequality in the CEE region was on average higher than in the rest of Europe, by 3 to 5 percentage points. In less than two decades, the CEE countries radically transformed their income distributions from relatively equal (Gini index of less than 25) to highly unequal (Gini index of 35 and above). Notably, the survey-based estimates point to declining average income inequality in the CEE region after 2005, leading to near-convergence with the average for the rest of Europe. On the other hand, DINA data suggest a much slower pace of inequality convergence, if any. It is also worth noting that the Ginis based on DINA are 8 to 9 percentage points higher in 2019 than those based on survey data. This is a result of much better coverage of top incomes in DINA (thanks to using data from income tax records) and capital income (such as dividends) which are often missed in household surveys.

Determinants of income inequality increase in the early post-transition years

The rise in income inequality in CEE countries in the early 1990s, after the transition from centrally planned to market economies, came as no surprise. Before the transition, socialist economies of the region shared severe shortages, very low levels of human capital investment, uncompetitive management, largely nationalized physical capital, poor services, and full, but very inefficient employment. The latter was accompanied by an administratively compressed wage structure, which was suddenly liberated in the early 1990s; together with the growth of the private sector, this liberalization contributed to the income inequality surge. In the late 1990s, income inequality generally stabilized (with some exceptions and later fluctuations) in post-socialist countries that later joined the EU. Since then, however, income inequality has reached very different levels, with Bulgaria, Serbia, and Romania being the most unequal by the end of the 2010s, followed by the Baltics, Poland, Albania, and Croatia. These countries are currently significantly more unequal than non-Eastern Europe on average. On the other hand, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Czechia kept a relatively low level of income inequality through the entire three-decade period, while Bosnia and Herzegovina, Hungary, and Moldova reached moderate inequality levels. These between-country differences stem from both the initial pace and order of the economic reforms, which differed significantly between countries, and from the policies adopted afterwards.

The relaxation of government controls in wage determination led to an increase in earnings dispersion. Interestingly, earnings inequality has increased both in countries that adopted fast and decisive market-oriented reforms, such as Czechia or Poland, and in countries where reforms were slow and gradual, such as Bulgaria or Romania. The dispersion occurred both in the expanding private and shrinking public sectors [5]. Moreover, nearly full employment, which was the goal of socialist regimes, turned out to be unsustainable in the new economic reality due to its high inefficiency. This resulted in an enormous outflow of the workforce from employment to either unemployment or inactivity, which further increased income inequality.

The rise of earnings inequality in the first years of the transition was partially a result of a rise in educational premia for highly skilled workers. For example, within just five years of transition, the wage premium for university graduates in the Baltics, compared to primary-educated workers, rose from 11% to 69%. During transition, old labor skills (such as command of the Russian language or managing a socialist enterprise) were largely devalued. New firms, especially foreign ones, introduced new freedom in wage setting. Increased wage dispersion resulted from a race between technological development and education, with technology being the winner. Even though the share of the population with at least secondary education rose significantly in all post-transition countries, the education systems had limited capability to adapt quickly to technological change and to adjust human capital accordingly. This resulted in a skill-biased technological change.

The introduction of fixed-term contracts was another labor market mechanism that emerged after the transition. On the one hand, the so-called “flexibilization” of the labor market helped to protect vulnerable workers (youth, women, the low-skilled) from unemployment. It also eased labor reallocation in a period of intense job creation and destruction and supported firms in coping with uncertain, transition environments. On the other hand, it created a dual labor market, with a primary sector of higher productivity and higher wages and a secondary sector with low-wage and low-productivity positions, poor working conditions, and insecure job traps.

Market reforms caused a massive shift of the workforce from the state sector to the private sector. This movement was accompanied by a significant rise in self-employment, which was essentially non-existent before transition in most countries, with the notable exception of Hungary, which relaxed regulations and partially liberalized the economy already in the communist era. On the one hand, self-employment—similarly to fixed-term contracts—could be seen as an alternative to unemployment, especially in heavy industry regions that were hardest hit by the progressive deindustrialization. From this perspective, the growing popularity of self-employment served to reduce inequality. On the other hand, many small businesses benefited from early entrance into emerging sectors of the now market-oriented economy and grew enormously over time, turning their founders into the new economic elite. The rise of private capital has generally aggravated income inequality in ex-communist countries since capital income is typically more unequally distributed than labor income [5].

Another mechanism that yielded high returns to its beneficiaries was privatization. In the majority of transition countries, privatization of state ownership lacked transparency. In some of them, for example Bulgaria, it even took the form of “insider privatization,” “asset stripping,” and “nomenklatura privatization”—in other words, it created opportunities for the concentration of resources in the hands of a small elite. It led to unjustified privileges and the formation of large private wealth, especially in the case of privatization of large state-owned enterprises. It should be noted, however, that some studies find that a statistically significant pro-inequality role was only played by large-scale privatization and infrastructure reforms, whereas privatization of small enterprises proved to be beneficial for those in the bottom deciles of the income distribution [6]. It should also be noted that a large portion of national wealth was transferred to citizens in a rather equitable way through privatization of housing to tenants at below-market prices. For example, homeownership rates between 1980 and 2010 grew from 26% to 86% in Estonia, from 36% to 81% in Poland, from 53% to 79% in Czechia, from 69% to 78% in Slovenia, and from 71% to 90% in Hungary. Thus, growing homeownership rates could play a mitigating role in increasing inequality.

Inequality developments since the 2000s

A study of labor incomes shows that between 2002 and 2014 wage inequality levels decreased in almost all CEE countries, with disproportionately large increases in wages at the bottom of the wage distribution [7]. The authors conclude that three main factors contributed to the wage inequality decrease: (i) labor code reforms associated with the (anticipated) EU accession that, among other things, increased workers’ bargaining power, (ii) consistent minimum wage increases, and (iii) large migration outflows to Western European countries. The latter factor likely decreased labor income inequality because the foreign demand for migrant workers concerned mainly the low-skilled workforce, thereby increasing workers’ outside options and leading to an increase in their domestic wages. The only Eastern European country that experienced a (slight) increase in wage inequality was Czechia, which experienced a decrease in the minimum wage expressed as a fraction of the average wage. At the same time, Czechia had the smallest migration outflows in the CEE, with less than 2% of the population living in other EU countries, compared to the maximum of nearly 12% observed for Romania [7].

Inequality increases in the CEE countries in the 2000s observed using DINA data may be due to capital-biased technological change and participation in a new phase of globalization. While data limitations preclude studying these effects for all ex-communist countries, a recent study provides evidence for Poland [8]. It finds that since the 2000s the top 1% income group in Poland is largely composed of those earning business income. This has been associated with increasing capital in the economy after EU accession and a growing share of capital in GDP. These effects could result from capital-augmenting technological change brought through foreign direct investments, trade-induced shifts toward capital-intensive sectors, and the rising market power of multinational companies [8]. However, more research using detailed, individual income data from tax sources is needed to verify these mechanisms.

During the Great Recession of 2008–2012, the level of income inequality increased in a statistically significant way for Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, and Slovenia, but did not increase in other countries under study. For most of the countries with significant increases in inequality, a falling full-time employment rate during the recession played the biggest role in explaining changes in inequality. At the same time, interestingly, increased part-time employment had either no impact on inequality or was rather inequality-decreasing. With respect to changes in the incidence of temporary jobs, there was no impact on income inequality.

Role of government redistribution

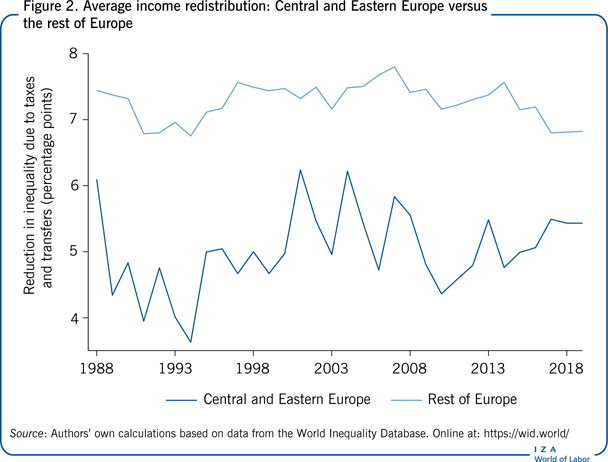

Income redistribution refers to all policies that transform the pre-tax pre-transfer income distribution to the post-tax post-transfer one. More extensive income redistribution through higher income taxes on the rich and transfers to the poor can reduce income inequality, at least in the short term. However, redistribution policies could also have negative impacts on income distribution, for instance, through discouraging labor market participation of welfare recipients. Figure 2 traces average income redistribution in the CEE region compared to the rest of Europe. It suggests that the initial spike in income inequality during transformation (from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s) is associated with a sizable fall in income redistribution of about 2.5 percentage points. It could be, therefore, that the observed inequality growth in the early phase of economic transformation was partly determined by reduced income redistribution. However, this overall trend masks important differences between countries. For instance, in Estonia, the state withdrawing from its formerly large redistributive functions contributed to the rapid rise in inequality. In Latvia and Lithuania, by contrast, the state is said to have retained a significant role in shaping inequality. However, all three Baltic countries introduced flat personal income taxes in the mid-1990s—a move followed by several other ex-communist countries since 2001 (Albania, Montenegro, Romania, Russia, Serbia, and Slovakia). Paradoxically, in some countries pensions pushed inequality up, whereas other social transfers were too small or too poorly targeted to make a difference [9]. Other studies find, however, that income inequality among social transfer recipients increased after the transition. In Slovenia, low inequality is largely attributable to the relatively efficient tax and social policy measures in redistributing incomes. In general, reform strategies that were more coordinated were better able to keep inequality at relatively low levels [10].

Since the mid-1990s researchers observe a slightly increasing trend in income redistribution in the CEE region. This may be related to the fact that individuals’ demand for redistributive policies grew in most of the CEE countries during the 1990s and 2000s. In addition, Eastern Europeans have on average a higher demand for redistribution than people in other European countries. However, as shown in Figure 2, the actual average income redistribution in post-socialist countries is currently about 1.5 percentage points lower than in the rest of Europe.

Wealth inequality

Relatively little is known about wealth inequality in Eastern Europe. Until the 2010s, there was no reliable data for measuring wealth and its distribution in the region. The situation improved recently when some CEE countries were included in the Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS) run by the European Central Bank. The survey has provided wealth distribution microdata for Slovakia since 2010, and since 2013/2014 it has added data for Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, and Poland. However, these data cover only a very recent period and the evolution of wealth distribution in the CEE region from socialism until the 2010s remains largely unknown.

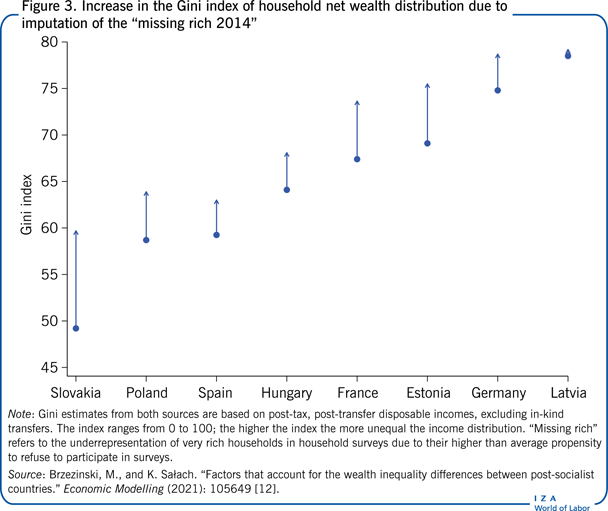

The problem of underrepresentation of top values in household surveys (“the missing rich” problem) pertains also to wealth distribution data. In the absence of detailed administrative data on wealth, researchers have relied on imputing to survey data the top wealth observations via estimations using global and national lists of rich persons (such as Forbes’ The World's Billionaires list). Figure 3 shows the results of such an exercise for five CEE and three selected Western European countries [11]. Strikingly, the results show that adjusted wealth inequality levels in the CEE are comparable to those in matured, advanced market economies. In particular, the Gini index for wealth inequality for Estonia and Latvia is close to that for Germany—the most wealth unequal non-CEE country. For Poland and Hungary, the top-corrected wealth inequality is comparable to that of Spain. These results seem surprising, as wealth distribution had been significantly compressed under socialism and the process of differential wealth accumulation in the market economy setting began only three decades ago. One factor that could, at least partly, explain high levels of wealth inequality in the Baltic countries is the privatization of business and other state assets, which these countries implemented the most quickly and radically in the CEE region. They were also the regional leaders in deregulating and liberalizing their economies, which could have had an inequality-increasing effect. More generally, increasing income inequality could lead to more wealth inequality in the CEE countries, as both types of inequalities are usually correlated.

Another factor that could explain relatively high wealth inequality levels in the CEE is the fact that personal wealth or inheritance taxes either do not exist at all or play a negligible role in the region's fiscal systems. Low wealth inequality in Slovakia seems to be related to a very high rate of homeownership (about 90%)—the highest in the euro area. Differences in homeownership rates explain up to 42% of the difference in wealth inequality across CEE countries when measured using the Gini index, and as much as 63% to 109% when a bottom sensitive inequality measure is used (the ratio of the median to the 25th percentile of the wealth distribution) [12].

An important study uses Forbes’ billionaire data to approximate wealth distribution in Russia over 1995–2015 [13]. It shows that wealth inequality increased substantially over this period, reaching a level comparable to that of the US and much higher than either China or France. According to the study's estimates, the top 1% wealth share in Russia exceeded 40% in 2015, while for the CEE countries displayed in Figure 3 it ranges from 20% to 35%. It may be hypothesized that the radical voucher privatization of national assets conducted in the early 1990s, as well as other privatization schemes that led to the rise of oligarchs, contributed to the explosion of wealth inequality in Russia.

Limitations and gaps

While there has been significant recent progress in measuring income and wealth inequality in Eastern Europe, the availability of high-quality income and wealth data is still limited. For example, there is no reliable information on the pre-2014 trends in wealth distribution using household survey or administrative data. For many ex-communist countries, data on income distribution from fiscal or other administrative sources are scarce. The existing inequality estimates for post-socialist countries are still based mainly on household survey data and, therefore, are probably of lower quality than estimates for other European states. Research on the economic determinants or consequences of the post-1989 income inequality eruption in the region is sparse and should be re-evaluated in light of new inequality estimates based on DINA. Currently, very little is known about the impact of redistribution or pre-distribution policies (mechanisms shaping the pre-tax pre-transfer income distribution such as regulatory, education, or health policies) on the final income distribution in post-socialist countries.

Summary and policy advice

Recent research provides evidence that income inequality in Eastern Europe during the transition to market economies has increased significantly more than previously thought. Wealth inequality in some ex-communist countries exploded to reach the highest levels in Europe, while several others reached levels found in matured capitalist economies. Market reforms, the rise of private capital, and limited redistribution all contributed to the elevation of inequality in the region. To bring Eastern European income inequality levels closer to those observed in other parts of Europe, governments should engage more actively in pre-distribution and redistribution policies. Unfulfilled citizens’ demand for redistribution in many CEE countries could be a reason for a recent political trend toward illiberalism and populism. Concerning pre-distribution, CEE countries should reform policies shaping market income distribution such as financial sector regulation, minimum wage legislation and labor union rights, the availability and quality of health and education services, and others. Responding to high public demand for redistribution, more extensive redistributive policies should be implemented. This could be achieved using more progressive taxation of personal incomes and transfers to the poorer parts of the population. The latter should be achieved using employment-conditional low-wage subsidies, which have been shown to reduce poverty and increase employment in the US, the UK, and other advanced countries. Given that wealth inequality in some post-socialist countries, notably in the Baltics, is among the highest in Europe, there is a rationale for introducing net wealth or inheritance taxes in those countries.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Financial support from the Polish National Science Centre through grant no. UMO-2017/25/B/HS4/01360 is gratefully acknowledged.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Code of Conduct. The authors declare to have observed the principles outlined in the code.

© Michal Brzezinski and Katarzyna Sałach