Elevator pitch

The relationship between climatic shocks, climate related disasters, and migration has received increasing attention in recent years and is quite controversial. One view suggests that climate change and its associated natural disasters increase migration. An alternative view suggests that climate change may only have marginal effects on migration. Knowing whether climate change and natural disasters lead to more migration is crucial to better understand the different channels of transmission between climatic shocks and migration and to formulate evidence-based policy recommendations for the efficient management of the consequences of natural disasters.

Key findings

Pros

Migration can help people cope with the adverse effects of climatic shocks by providing them with new opportunities and resources.

Remittances increase after disasters and play an important role in mitigating the adverse effects of climatic shocks and natural disasters.

Climatic factors, such as hurricanes, floods, droughts, or rainfall and temperature variations, may increase international migration through their effect on internal migration.

Agricultural productivity represents one of the pathways that can explain the relationship between climatic shocks and migration.

Public intervention both before and after disasters helps build resilience and can explain why migration responses differ depending on the types of shocks.

Cons

The migration response to disasters depends on the nature of the shock (slow vs rapid onset events), its severity, and the vulnerability of the affected people.

Due to liquidity constraints, poor people might not be able to migrate in the aftermath of climatic shocks.

In developing countries, international migration due to disasters may be driven by highly educated people, which may foster brain drain in a vulnerable context.

Author's main message

Climate change and natural disasters cause people to migrate if they do not have alternative mitigation strategies, are forced to move because of the shock, and can afford migration costs. Consequently, disaster management requires a holistic approach, where migration and remittances, which are private mechanisms, should be considered along with public intervention. In addition to helping households build resilience by, for example, investing in infrastructure in vulnerable areas, providing social protection, and allocating aid rapidly and efficiently, enhanced international cooperation is needed to reduce the human impact of climate change.

Motivation

Climate change and natural disasters are two of the major global threats to socio-economic progress for current and future generations. Although the relationship between climatic factors and migration has probably always existed, the mechanisms through which the former impacts the latter are not yet fully understood. For policymakers, it is important to know what can motivate or prevent people from migrating in the aftermath of a disaster. It is also crucial to understand the role of shock intensity and determine whether the relationship between climate change, natural disasters, and migration is direct or affected by other factors. Moreover, knowing if people engage in internal rather than international migration would probably not have the same implications for the cost and affordability of relocation, policy management of migrants, or the size of future remittances. For all these reasons, empirical evidence is needed to inform policymakers about the different migration responses to climate change and natural disasters. This will help design better policies to protect the most vulnerable populations from climatic shocks and their consequences.

Discussion of pros and cons

Migration as a coping strategy for climate change and natural disasters

The mitigating role of migration

Population movement is a natural way to deal with climatic shocks, particularly when livelihoods are destroyed. Migration can be considered as an adaptation strategy when disasters occur because it helps mitigate the adverse effects of the shocks by providing new opportunities and resources to affected people. It also serves as a coping strategy when other solutions have failed. For instance, in the case of drought, potential solutions, which in some cases may be survival strategies, can include changing consumption patterns by reducing the number of daily meals, selling household assets, using food reserves, and benefiting from solidarity through gifts, loans, and aid. Having many possible coping strategies will reduce the likelihood of migration due to shocks.

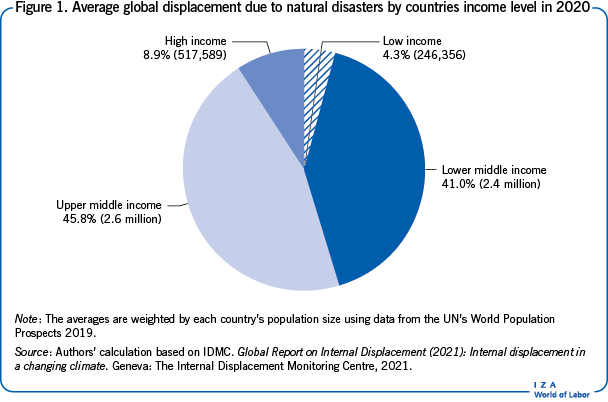

In 2020, developing countries (including low-, and middle-income countries, based on World Bank’s classification ) accounted for 91.1% of global internal displacement due to disasters. Most of the displacements are from middle-income countries (Figure 1). Moreover at a country level, this corroborates the fact that people at the extremities of the income distribution do not necessarily migrate in the aftermath of disasters. Indeed, the poorest cannot afford to migrate and the richest have other mitigation strategies, such as the possibility to recover their lost assets or better access to effective infrastructure and social services, which allow them to cope with disasters without migrating. Therefore, people at the middle of the income distribution are those who do not have many alternatives at their disposal to deal with natural disasters and, at the same time, can afford migration costs.

However, it is important to point out that the rather low rates of disaster-related migration from poor and high-income countries do not necessarily mean that the poorest and the richest people in a specific country do not migrate. There is some heterogeneity within developing countries, which shows that the level of vulnerability of an individual as well as the intensity and severity of the shock also matter when it comes to the relationship between disasters and migration. Vulnerability is correlated with factors such as exposure to shocks, poverty level, social structure, assets and income diversification, and the political situation. For instance, people living in a politically unstable environment have fewer survival strategies available to them than those living in a peaceful one. The intensity refers to the violence of the disaster-related shocks. The severity of the shock is measured through the frequency, temporal spacing, and spatial distribution of the event, and the way people affected perceive the shock. The frequency of shocks represents the number of events in a given period. The temporal spacing measures the elapsed time between two events. The spatial distribution characterizes the extent of the shock in a given region; for instance, an event that is isolated to a specific area is easier to deal with than an event affecting an entire country. Finally, the way people perceive shocks is shaped by expectations and experiences from previous events.

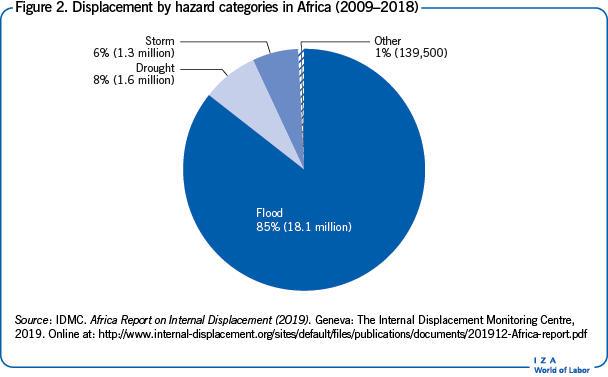

The role of vulnerability and severity is highlighted in the case of Bangladesh over the period 1994–2010. Moderate flooding, as compared to less severe flooding, increased an individual's likelihood to move locally, but decreased her likelihood to make a long-distance migration; this was especially true for vulnerable groups such as the poor or women. Moreover, households that were not directly affected by the flooding but lived in areas with severe crop failure were more likely to move [2]. Figure 2 provides a good illustration, for the case of Africa, that all types of natural disasters are not equivalent in terms of their effect on migration. Flood was the main source of disaster-related displacement between 2009 and 2018, with 18.1 million displaced people, accounting for 85% of total disaster-related displacement during the period.

The association between the extent of the migration response and the severity of the disaster is also observed in developed economies. Evidence shows, in the case of the US, that severe disasters increase net out-migration from a county, while migration response to milder disasters is smaller at the county level [3].

The role of remittances

Migration can serve as a coping mechanism through remittances sent back by emigrants to communities affected by climatic shocks and natural disasters. Remittances help increase the resilience of households to natural disasters and reduce their vulnerability to the effects of shocks. Migrants’ transfers provide insurance to the left-behind in case of shocks. Consequently, remittances help households deal with income shocks caused by disasters. Evidence shows that remittances have a stronger poverty reducing-effect in countries hit by natural disasters [4], confirming the insurance role of remittances against the economic costs of natural disasters. This highlights the importance of lowering the costs of sending remittances.

Impact of climate change and natural disasters on migration

Internal vs international migration

Studies that look at the impact of climatic factors on internal migration use the urbanization rate, measured as a country’s share of urban to total population, as a proxy for rural-urban migration due to the unavailability of comparable internal migration data across countries and over time [5], [6]. This is based on the assumption that most internal population displacement is due to rural-urban migration. However, evidence on the link between climate change, natural disasters, and internal migration is rather mixed and varies depending on the nature of shocks and across regions. On the one hand, natural disaster is found to increase the urbanization rate in developing countries [6]. On the other hand, evidence shows that increasing temperatures over a long period of time positively affect internal migration in middle-income countries but not in low-income countries [5].

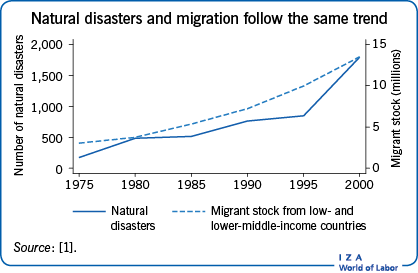

Evidence also shows that climatic shocks and natural disasters could lead to international migration [1], [7], [8]. For instance, natural disasters closely related to climate change such as storms, floods, wet mass movements, drought, wildfire, and extreme temperatures, have been shown to boost migration from developing countries to the six main OECD destination countries. Furthermore, this effect is primarily driven by migration of highly educated people [1]. Education is correlated with income, which may indicate that those highly educated people can afford migration costs. This suggests that climate change-related disasters may lead to brain drain from developing countries.

Migrant networks have also been found to be key to climatic shock-induced international migration as they facilitate immigration by reducing the fixed cost of migration. There is evidence that countries of origin with higher prior migrant stock in the US can benefit to a larger extent from formal sponsoring for legal, permanent immigration into the US [8].

Another body of evidence finds that climatic shocks such as weather anomalies affect international migration through their effect on internal migration, which is called an “economic geographic channel” [7]. For instance, in the case of sub-Saharan Africa, weather anomalies have been found to be positively associated with rural–urban migration because of their effects on the agricultural sector. This internal migration, in turn, leads to an increase in international migration by raising the number of workers in cities, translating into lower wages and increasing people’s willingness to move internationally in search of higher wages. Weather anomalies can also lead to high international migration through a so-called “amenity channel” by increasing the spread of disease and risk of death [7].

The role of liquidity constraints: Slow vs. rapid onsets and temporary vs. permanent migration

The positive relationship between climatic shocks and migration has been challenged in the economics literature. There is some evidence showing that climatic shocks do not necessarily lead to more internal or international migration if the affected people are burdened by liquidity constraints or if they have to deal with slow-onset events such as slowly changing temperatures [5] or droughts [9]. Conversely, it might be argued that when faced with rapid-onset events such as cyclones, storms, and floods, people could be forced to move because they lose everything all at once, which is not necessarily the case with slow-onset events [9].

Studies also show that due to liquidity constraints, victims of rapid-onset events are more likely to embark on short-distance migrations [6] or short-term relocations, rather than on permanent or long-distance migration [2]. Viewed through the lens of migration costs, liquidity constraints can be extended to more general socio-economic costs such as the existence of important migrant networks in possible destination places. In the case of international and permanent migration for example, migrant networks can facilitate new migration in the aftermath of a climatic shock by providing a less costly, legal route to immigration, through such provisions as family reunification immigration policies [8].

Indirect effects of natural disasters on migration

Some studies have found that climatic factors do not have any direct impact on migration, but an indirect one [6]. One possible transmission channel is agricultural productivity [5], [10]. This means that climatic shocks initially reduce agricultural productivity, which, in turn, leads to increased migration.

Evidence from economic history provides a good example of how negative climatic shocks affect population movement through their effects in the agricultural sector. For instance, in the agriculturally dependent plains counties of the US in the 1930s, large dust storms due to prolonged severe drought conditions and intensive land use caused permanent soil erosion. This phenomenon, known as the American Dust Bowl, incurred substantial agricultural costs that were mitigated, to a degree, by a relative population decline caused by out-migration from high-erosion counties to low-erosion ones [11].

This example illustrates how disasters affect internal migration through their effects on the agricultural sector. However, recent evidence shows that climatic shocks (i.e., long-term events) can also affect international migration through agricultural productivity. For instance, based on annual migration data from 163 origin countries and 42 destination countries, which are mainly OECD countries, during the period of 1980 to 2010, higher temperatures have been found to increase international migration flows, but only for countries that are highly dependent on agriculture [10]. Other indirect channels include negative effects on firm productivity and the associated lower wages in the areas affected by climatic disasters, which encourages out-migration in search of better economic opportunities [3].

The role of public intervention

Public intervention is crucial for reducing a population’s vulnerability to climatic shocks and improving resilience [12]. For instance, in the US in the 1920s and 1930s, there were outflows of migrants from areas that experienced a large number of tornadoes, while those areas affected by floods had net inflows of migrants. The difference in migration responses in the aftermath of tornadoes and floods can be explained primarily by early public intervention. Government authorities invested ex-ante in the infrastructure and protection of flood-prone areas, which made them more resilient to shocks and improved their attractiveness as living options. Such interventions did not happen in tornado-prone areas [13].

Ex-post public intervention is also key to the decision to migrate or stay. Again, in the case of the US, evidence shows that subsidies can influence the decision of neighboring households to remain in their area after it is hit by a disaster. Evidence using data from 2004 to 2010 shows that this is what happened in the case of post-Katrina rebuilding in New Orleans under the Louisiana Road Home rebuilding grant program [14].

In Bangladesh, over the period between 1994 and 2010, the occurrence of floods did not lead to high migration from affected areas, while crop failure caused a dramatic increase in migration. Again, the different migration reactions can be attributed to authorities’ responses to the disasters; assistance was provided in the aftermath of floods, while it was not the case for crop losses [2].

Limitations and gaps

Despite increasing interest in the relationship between climate change, natural disasters, and migration in the scientific literature and among policymakers, it is still difficult to achieve consensus on the exact nature of the relationship. Consequently, there is, above all, a need for more evidence at the microeconomic level. Due to diverse factors such as differences in adaptation capabilities, data imperfection, differences in variable measurement, and unobserved cultural/anthropological differences, a common pattern of migration response to weather shocks can be difficult to establish even in the context of a region-specific analysis, and even more in the context of larger heterogeneity in the space under consideration. This pattern might therefore be context-specific [15].

Long duration panel datasets are also needed to better understand the long-term effects of disasters, though more efforts are currently underway in this regard. Having access to more information on the socio-demographics of migrants in the aftermath of shocks as well as knowing how people displaced due to climatic shocks and natural disasters differ from conventional migrants such as labor migrants will help understand the consequences of disasters for both the origin and destination areas. Additional information on the affected populations as well as on those who relocate within their origin countries following a post-disaster migration will also help shape specific policy interventions.

Finally, a crucial area for further research is to investigate return migration to areas that were hit by disasters. It is also important to know more about the impact of disaster-induced migration on the well-being of both migrants and those left behind. This is particularly important because it could, for instance, affect labor market outcomes in both origin and destination countries, and inform on the integration of migrants in the receiving countries.

Summary and policy advice

Natural disasters can occur anywhere; however, developing countries are the most vulnerable to their effects due to lower resilience and weaker coping mechanisms. Migration can play an important mitigating role in the aftermath of natural disasters. This role is reinforced by the impact of remittances, which help build households’ resilience ex-ante and reduce the adverse effects of shocks on their livelihoods ex-post. Disasters can lead to internal migration and, depending on the circumstances, to international migration. People must be able to afford to migrate; this makes liquidity constraints an important element of the relationship between disasters and migration. Liquidity constraints can also explain why people do not migrate in the case of slow-onset events. Moreover, even if people are forced to move, as is often the case with rapid-onset events, liquidity constraints may force them to relocate only temporarily or embark on short-distance migrations. Disasters related to climate change can also affect migration through their effects on agricultural productivity, typically by reducing crop yields. Finally, evidence shows that the type of policy intervention before and after disasters can explain why different disasters induce different migration responses.

Migration and remittances, which are private mechanisms for dealing with shocks, should be considered complementary to public intervention, and not as substitutes. If only migration and remittances are available as mitigation strategies against disasters’ effects, this can lead to increased inequality between migrant households and non-migrant households, as well as between remittance receivers and non-receivers. Thus, disaster management requires a holistic approach, which takes into account both private and public mechanisms for protection and intervention. Governments should thus help channel migration when necessary and alleviate the cost of sending remittances. Moreover, ex-ante, public authorities can help households build disaster resilience through, for instance, better social protection, effective insurance mechanisms, and economic diversification to reduce dependence on agriculture. It is also important for governments to intervene rapidly and have strong institutions that can manage aid flows after disasters [12].

However, while it is largely accepted that climate change and natural disasters are one of the main challenges of the contemporary era, it is still difficult to achieve consensus on an appropriate course of action, particularly between developed and developing countries. Private solidarity mechanisms are at work—for example, in the form of remittances—but the level of commitment needed on the global stage falls short of expectations. This raises equity issues because poor countries only play a small role in driving the climate change process compared to advanced economies, yet their increased vulnerability exposes them more than richer nations to its adverse effects. Climate issues have been at the core of political debates and have increasingly involved citizen action. Addressing the issue of climate change requires better governance on a global scale, with more efficient aid allocated to vulnerable countries as well as better migration policies toward migrants from those countries.

Migration in the aftermath of climatic shocks or natural disasters should not be perceived as a threat for many reasons. First, most migrants move internally or to neighboring countries. Second, due to the prospect of remittances, migrants can help those left behind deal with shocks. Finally, migration remains a human right, above all in the case of climate-related disasters. Migrants should thus be received and integrated into host societies, for the benefit of all.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Previous work of the author contains a larger number of background references for the material presented here and has been used intensively in all major parts of this article [12]. Version 2 of the article contains new figures and adds new Key references [3], [4], [8], [9], [14], and [15] as well as new Additional references.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Linguère Mously Mbaye and Assi Okara

Definition of climatic shocks and natural disasters

Source: For detailed references, see Table S1 in the supplementary information of Bohra-Mishra, P., M. Oppenheimer, and S. M. Hsiang. “Nonlinear permanent migration response to climatic variations but minimal response to disasters.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences111:27 (2014): 9780–9785. Online at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1317166111