Elevator pitch

About one in five workers across OECD countries is employed part-time, and the share has been steadily increasing since the beginning of the economic and financial crisis in 2007. Part-time options play an important economic role by providing more flexible working arrangements for both workers and firms. Part-time employment has also contributed substantially to increasing the employment rate, especially among women. However, part-time work comes at a cost of lower wages for workers, mainly because part-time jobs are concentrated in lower paying occupations and sectors, while the impact on firms’ productivity is still not very clear.

Key findings

Pros

Part-time employment enables more flexible work arrangements for firms and a better work-life balance for workers.

Part-time work may increase firms’ productivity by lowering employee stress and health risk and by allowing employers to better adapt to variations in demand.

Part-time work may provide a means to enter or re-enter the labor market for many workers who might otherwise simply drop out of the labor force.

In particular, part-time work has contributed to higher employment rates for women in many countries.

Cons

Part-time employment goes together with lower hourly wages, mainly because part-time jobs are concentrated in lower paying occupations and sectors.

Segregation of part-time jobs may reflect personal choices but also discrimination if part-time workers are offered only low-paying jobs and lower career opportunities.

Part-time workers increase management costs for firms, which in turn tend to invest less in their part-time workers.

If associated with low pay and temporary contracts, part-time employment raises important concerns about living standards for current workers and future pensioners.

Author's main message

Part-time work substantially increases the flexibility of workers and firms, and has contributed to higher participation of women in the labor market in many countries. While the impact on firm productivity is not yet clear, part-time work is often accompanied by a wage penalty, a result largely of the concentration of part-time jobs in lower-paying occupations and sectors. Carefully designed family policies and a cultural shift in attitudes are needed to fight more effectively against discriminatory forms of segregation, provide effectively equal treatment for full- and part-time workers, and make the option of part-time employment useful and convenient for all occupational levels.

Motivation

Over the past three decades, part-time jobs have become a prominent feature of the labor market in Europe and North America. In recent years, there has been a widespread rise in the share of workers who are employed part-time, much of it involuntary, reflecting a shortage of opportunities for full-time employment.

From the perspective of workers, voluntary part-time jobs allow more family-friendly working-time arrangements. However, even when part-time jobs are a result of personal preference, they also entail some costs in terms of lower wages, lower job security, and fewer career opportunities. From the perspective of employers, part-time jobs are a useful tool to adjust work arrangements, but the effect on firm productivity is not clear. In theory, productivity could increase due to better work-life balance and less job strain, but it could also decrease because of lower commitment by workers or lower investment in training by firms. Overall, part-time work can boost labor force participation, improve work–life balance, and increase work flexibility; but at what cost for workers and firms?

Discussion of pros and cons

The importance of part-time work across OECD countries

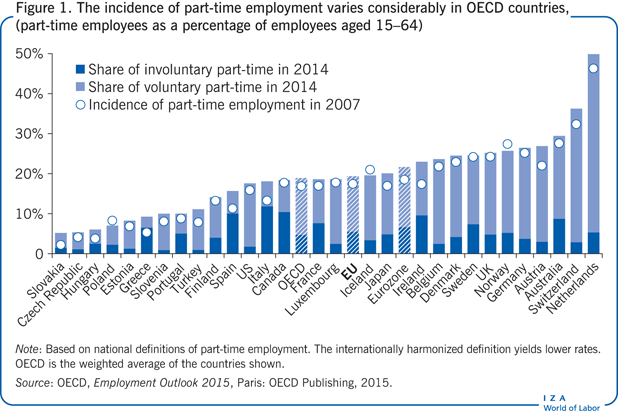

About one in five workers in OECD countries was employed part-time in the third quarter of 2014, and the share has been rising steadily since the onset of the economic and financial crisis in 2007 due to a shortage of full-time opportunities. There are important differences across OECD countries, however. Half the working population in the Netherlands has a part-time job, one-third in Switzerland, and more than a quarter in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the UK. By contrast, part-time employment is much less prevalent in Central and Eastern European countries, as well as in Greece, Portugal, and Turkey. Part-time work affects mainly women (two-thirds of part-time workers in OECD countries in 2014 were women) and is therefore closely linked to gender equality and family policies.

However, while part-time employment has been spreading in almost all OECD countries, an important difficulty in comparing part-time work across countries concerns how to define it. There is no universally accepted definition of part-time employment. A definition proposed by the International Labor Organization defines part-time work as “regular employment in which working time is substantially less than normal.” However, “substantially” needs to be quantified. The OECD distinguishes three main approaches to defining part-time employment: a classification based on workers’ perceptions of their employment situation, a cut-off (generally 30−35 hours a week) based on usual working hours, and a cut-off based on actual hours worked during the reference week. The internationally harmonized definition used in the OECD Labor Force Statistics is less than 30 usual hours worked on the main job.

National definitions of part-time employment cannot be used to resolve the issue because they vary from country to country (Figure 1). In most cases, national definitions imply a higher incidence of part-time employment than does the OECD internationally harmonized definition.

The definition of part-time employment should further distinguish between part-time jobs that are “short” (a few hours a week) and those that are “long” (closer to full-time work). The distribution of working hours in European countries based on the Structure of Earnings Survey shows two peaks, one around 20 hours a week and another around 30 hours a week. The effects of part-time arrangements on wages and productivity probably differ substantially according to whether the individual works a few hours a week or almost full-time. However, there is no common agreement on the cut-off between short and long part-time work, and the literature usually adopts a range of cut-offs.

Moreover, part-time work is further distinguished as “horizontal,” when the hours are reduced on a daily basis, or “vertical,” when the work is executed full-time but only during certain days of the week or, less commonly, certain months or years.

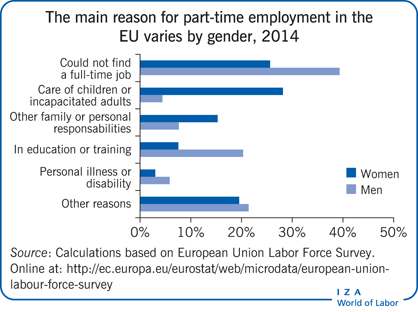

Another important difference is between voluntary and involuntary (or “economic”) part-time work. Once again, this aspect of the definition is not completely harmonized across countries. In most OECD countries, involuntary part-time workers are identified based on their response to a question about why they are working part-time. Responses vary from illness, school enrollments, and caring responsibilities to the inability to find a full-time job (see the Illustration); only individuals who give that last response are classified as involuntary part-time workers. In a few countries (including Australia, Japan, and New Zealand), involuntary part-time workers are identified as workers who work part-time but would prefer to work more. However, even voluntary part-time workers may not be fully satisfied by their employment status since they may be driven by external constraints (notably childcare availability) or they may want to work more but not full-time. For example, according to the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound), on average across European countries 17.5% of women working part-time voluntarily would like to work more hours (but not full-time).

In most countries, especially those where part-time work is widespread, working part time is most often a voluntary choice (see Figure 1). This is not the case in Canada, Greece, Italy, and Spain, where more than half of part-time workers would like to work more. The recent recession led to an increase in involuntary part-time work in most countries, reflecting a shortage of opportunities for full-time employment.

What is the impact of part-time employment for workers?

Wage gap for part-time workers

Based on the raw data, part-time workers in European countries are paid on average 20% less than full-time colleagues on an hourly basis. Part-time wage differentials can arise for a variety of reasons. Some people may prefer to work part-time and accept lower wages, notably young people working while still in school or older workers who, though retired from their full-time job, want to continue working for some more years, but not full-time. However, differences in worker preferences would not explain the wage penalty if the skills are similar and if part-time work does not increase costs for firms. Indeed, the raw data may simply mask the fact that part-time workers are not the same as full-time workers: they may be less skilled or less motivated. The pay gap may also reflect a segregation effect: part-time workers may be concentrated in low paying firms, occupations, or sectors and thus may be paid less irrespective of their skills and motivation. Segregation can reflect personal choices as part-time workers may refuse career opportunities and continue working in less demanding and therefore lower paying jobs. But segregation can also reflect discrimination if part-time employment and the type of occupation are not a choice but rather a constraint imposed by employers unwilling to offer better job opportunities to the workers they are discriminating against.

Firm costs and labor market institutions

From a company’s point of view, managing human resources entails some fixed costs, for example administrative costs, costs of hiring and firing, and fringe benefits that are independent of working hours. Having part-time workers may increase coordination costs by worsening communication gaps or jeopardizing output continuity. For these reasons, part-time workers may be relatively more costly and therefore may receive lower wages to the extent that employers pass on these additional costs to workers by reducing part-time wages.

Labor market institutions, notably unions and tax and benefit systems, can also affect the wages of part-time workers. In most countries, part-time workers are less unionized and thus have lower bargaining power. The typical example is overtime premiums: in most sectors and companies, overtime work is associated with a wage premium for full-time employees who exceed contractually fixed working hours, while extra hours for part-time workers generally do not give rise to an overtime premium. Fiscal policies are another important factor. Some countries, like Belgium, France, Germany, and the UK, promote part-time employment by subsidizing it through reduced social security contributions or tax relief, which lowers labor costs for employers (a policy that is relevant for studies using the wage bill at the firm level). Moreover, since income taxes are based on total annual income and the tax system is progressive, full-time employees have to be paid a higher gross hourly wage than part-time employees in order to get the same net hourly wage as part-time workers. Hence, trade unions could accept higher gross hourly wages for full-time employees to give the same net hourly wage to all employees. The amount of payroll taxes for employers, however, has the opposite effect because, in general, per-hour payroll taxes decrease with the number of hours worked.

Estimates of the wage gap

Econometric analyses have confirmed the existence of a wage gap between full-time and part-time workers by estimating wage equations, with (the logarithm of) hourly wages as the dependent variable and education, work experience, and job and labor market characteristics as explanatory variables. For most countries, studies estimate a 10−30% wage penalty to part-time employment, but estimates vary considerably according to the data and methodology used. Two notable exceptions seem to be Norway and Sweden, where the adjusted wage differential seems to be in favor of part-time workers [1], [2]. These exceptions are attributed to the specific characteristics of their labor markets, notably strict rules against discrimination and a generous family policy enabling women to combine work and family life.

Some of the difference in the hourly wage between part-time and full-time workers is explained by differences in their personal and job characteristics. Indeed, on average, part-time workers are more likely to have less education and to work for small firms that offer lower training or promotion opportunities. Estimates of the relative weight of these components in explaining the wage gap find that differences in personal characteristics usually explain only a small part of the part-time wage penalty. Far more important are differences in job characteristics: occupation for women, and industry and contract type for men. Several analyses have found that the part-time wage penalty completely (or almost completely) disappears once detailed variables for occupation and sector are included in the regressions [2], [3], [4], [5]. These findings suggest that almost the entire unexplained wage gap is due to occupational segregation. In other words, once detailed information on occupation and sector is taken into account, part-time and full-time workers are paid very similar wages. However it remains important to stress that while occupation and sector segregation can reflect self-selection or personal choice, such segregation may also hide direct discrimination by employers.

Going beyond a static analysis studies find that cumulated skills, on top of personal and job characteristics and changes in preferences over time, also matter in explaining the wage gap. Part-time workers accumulate less experience and skill over time [6], thus remaining stuck in lower paying occupations or less skill-intensive sectors. In other words, rather than being an inherent feature of individual workers, segregation may develop over time because of fewer promotions and career opportunities [7]. Again, this situation could be the result of personal preference, with an individual deciding to pass up promotions or training to avoid more demanding tasks higher up the hierarchy, or it could reflect discrimination. Moreover, when part-time work alternates with spells of non-employment, it can more easily become a “trap” with few opportunities to escape [8].

Finally, on top of basic pay, part-time workers may also suffer from a gap in bonuses and extras (fringe benefits, health and life insurances, pensions, and the like) compared with full-time colleagues, but there is no clear evidence on this issue, mainly because of a lack of detailed data on such extras.

Why do many workers choose part-time employment despite the wage gap?

In conclusion, the evidence paints a consistent picture in which part-time work, on average, goes together with lower hourly wages due to segregation into low paying occupations and sectors (but, the drivers of segregation are not fully clear). Why then does a substantial share of workers still willingly seek part-time employment? Some people might not have a real choice, because of family constraints, but some workers may willingly trade lower wages for other aspects of the job package that appeal to them.

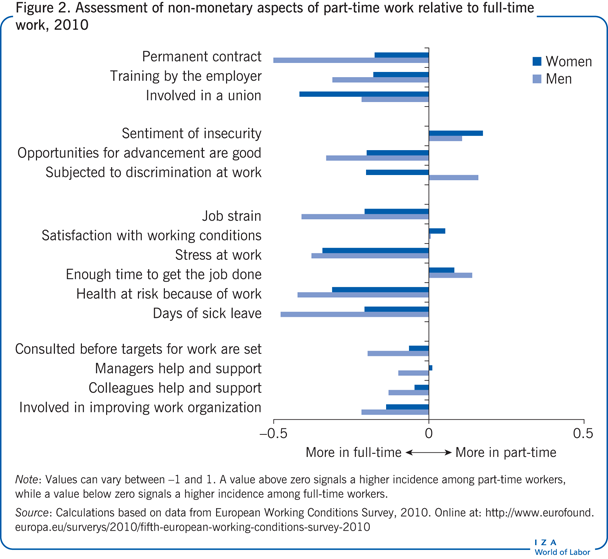

Figure 2 compares the incidence of some non-monetary aspects of work for part-time workers to the incidence for full-time workers. Compared with full-time workers, part-time contracts go together, on the one hand, with a lower share of permanent contracts, lower training, less involvement with a union, and lower opportunities of advancement, and, on the other hand, with less stress and lower job strain (defined as a high level of work stressors combined with insufficient resources and support to accomplish job duties), enough time to get the job done, less concern about putting one’s health at risk, and fewer days off for sickness.

In summary, from a worker’s point of view, a part-time job means lower wages, even if this is due more to part-time opportunities being available mainly in low-paid occupations and sectors and less to factors that contribute to future earnings potential, such as training, promotions, and union membership. Part-time jobs also offer lower job security than do full-time jobs because they are often linked to temporary contracts. However, part-time jobs also offer better working arrangements, lower stress and job strain, and better work-life balance.

What is the impact of part-time employment for firms?

Having looked at the impacts of part-time employment from the perspective of workers, we now turn to consider the impacts from an employer’s perspective. Overall, in contrast to the relatively rich literature on the part-time wage gap, the empirical evidence on the impact on firms’ performance is still scarce. The evidence is limited to few countries and remains largely inconclusive.

Theoretical predictions of the impact of part-time employment on firm productivity

Theory suggests that the productivity of part-time workers might be higher than that of full-time workers because of lower stress, lower absenteeism, better work–life balance, and a more flexible work organization. These effects may vary according to the type of part-time employment. For instance, horizontal part-time workers, who work fewer hours a day than their full-time colleagues, could suffer less from fatigue associated with long working hours and thus might outperform their fatigued full-time colleagues, especially those who work overtime. In addition, productivity could be higher for part-time workers, who have to complete in less time what effectively remains a full-time workload, a phenomenon that could lead to a gap between productivity and wages of part-time workers. Moreover, using part-time workers might enable firms to reap productivity gains without increasing payroll costs, by extending opening hours or exploiting firm-specific capital more intensively. Flexible working hours and alternatives to the traditional full-time work schedule might result in both productivity gains and higher wages for part-time workers. For example, part-time wage premiums have been seen in some sectors facing seasonal or fluctuating demand, as employers pay higher wages to part-time workers in order to staff highly productive peak periods [9].

However, the productivity of horizontal part-time workers might also be lower than that of full-time workers because daily start-up costs imply that productivity picks up only slowly during the working day. As a result, a worker’s productivity during the last hour of work exceeds average productivity. Or productivity may be lower in the case of involuntary or short-term part-time work because people may feel less motivated and less engaged in their work. More important, productivity may be lower because of lower investments in training (see Figure 2). Part-time workers may be less committed to career goals and may pass on training opportunities, or employers may be less willing to invest in training part-time workers since the return would be lower than for full-time workers.

Empirical evidence

In the end, the impact of part-time work on firms’ productivity is a matter for empirical analysis. However, it is not easy to measure productivity and compare productivity patterns with wage differentials. Some recent studies have gone in this direction. They have used independent productivity measures that provide evidence on the impact of part-time work on firms’ productivity and the existence of productivity-wage gaps that result in rents for employers or workers deriving from productivity that is higher or lower than wages.

Some early qualitative evidence in the 1990s supports the notion that by allowing a better match of workplace operations with consumer requirements, part-time leads to an increase in productivity. Evidence for Germany shows that horizontal part-time jobs increase motivation and reduce absenteeism, while vertical part-time jobs allow companies to manage demand variations more efficiently (in industries such as tourism and banking, for example) [10]. The study also finds that shift-based part-time jobs might enable firms to extend operating hours, leading to more intensive use of capital.

Econometric evidence on pharmacies in the Netherlands shows that part-time employees increase productivity at the firm level by allowing more flexibility in work organization—for instance, by allowing full-time colleagues to take a lunch break while keeping the pharmacy open or by bridging any gaps between opening hours and the full-time work week [11]. However, the data used in the study were not longitudinal, so the results may be confounded by unobserved differences among firms (firm fixed effects) or unobserved shocks (for instance a firm or sector-specific crisis or boom) causing changes in the use of part-time work, rather than the opposite occurring.

Evidence based on longitudinal employer–employee matched panel data for Belgium, which allow directly comparing the effect of part-time employment on firms and workers, shows that male part-time workers employed more than 25 hours a week increase labor productivity at the firm level without a corresponding increase in wages [12]. Female part-time workers are as productive as full-time workers but are paid less. These two effects, through two different channels, generate rents for employers as a result of a positive gap between productivity and wages. This gap likely arises from the types of part-time jobs available to men and women: male part-time work is frequently related to training and collectively negotiated reductions in hours that do not affect hourly pay, whereas women often have to downgrade to more flexible jobs in order to accommodate domestic constraints.

Evidence on total factor productivity for Italy suggests that horizontal part-time work, is detrimental to productivity, in particular when the work is part time in order to accommodate workers’ requests and not because of company-specific needs [13].

Limitations and gaps

The two streams of the literature, on wages and productivity, are at very different stages of development. The debate on the wage penalty is certainly not closed, but it is at a mature level, while the debate on productivity is still in its infancy and needs much stronger research investments in the coming years. However, since studies of the wage gap rarely also consider productivity, it remains difficult to assess the role of discrimination beyond personal and job/firm characteristics. Combining the two streams of research using linked employer–employee data is therefore the key to properly assessing the origins of the segregation of part-time work in certain occupations and sectors and to proposing appropriate policies.

Finally, both streams of the literature face a common challenge: in general, they tend to approach part-time work as a homogeneous feature. However, part-time work can be long or short, horizontal or vertical, and voluntary or involuntary, and the impacts are likely to differ for men and women. The few studies that have considered this heterogeneity have found that the effects on both wages and productivity can be very different under these different conditions. To better inform workers, employers, and policymakers, future research on the topic needs to take into account the heterogeneity of part-time work.

Summary and policy advice

Part-time employment has been an important feature of efforts to increase the flexibility of labor markets since the 1990s. It has contributed to higher employment rates while also improving the work–life balance for many workers. However, it has also come with some costs for workers, notably in terms of wages and lower career opportunities. The cost–benefit analysis for firms is still not clear.

Lower wages are explained in the literature mainly as a mix of self-selection and segregation into certain lower-paying occupations and sectors rather than outright discrimination. This has led some studies to conclude that the penalty is driven by market factors and not by discrimination and that therefore it is not a matter of great policy concern. However, discrimination may also occur through occupational segregation [5]. Indeed, since the link between wages and productivity has not been properly analyzed, discrimination cannot be ruled out at this stage [12]. Moreover the combination of part-time, low pay, and temporary contracts, often in the context of ill-conceived tax and benefit systems, leads to (in-work) poverty and less desirable careers over time. Part-time work is a major correlate of low long-term earnings.

In the last 20 years, several policy initiatives have attempted to ensure equal pay and opportunities for part-time workers. However, in most cases these policies have not been able to counter the effect of increased segregation: direct discrimination may well have been replaced by indirect discrimination through imposed segregation in low-paying occupations or reduced career opportunities. The introduction of equal-treatment laws is associated with increased opportunities only in countries with relatively tight labor markets and most often only for men; no effect is found in countries with relatively high unemployment rates. It seems also that initiatives in the UK like the national minimum wage (1999), the part-time workers regulations (2000), and the right to request flexible working (2003) have made little difference in reducing the wage gap [4]. This lack of a wage effect is not especially surprising since implementation and enforcement of these initiatives usually require action by employees. Only workers with relatively stronger alternative job options are able to insist on their rights, while relatively weak workers might just accept a lower paying job in another sector or occupation.

Segregation occurs both across sectors and across occupations, with top positions blocked off from part-time workers as a matter of social and company culture. But family policies may also allow women at the bottom of the employment hierarchy to work full-time and eventually put rungs back in the career ladder. However, family-friendly policies must be designed carefully, since they have been shown to backfire fairly easily if not all workers with access to the policies use them, leading to further segregation of the weaker group of workers. Moreover, it is important that tax and benefit systems not create disincentives to take up or return to full-time work, especially for second-earners.

Finally, part-time work also raises some issues for future living conditions, since the pensions of part-time workers will likely be lower than those of full-time workers and may not be enough to make ends meet. The interaction between part-time work and tax and benefit systems, both during working age and in retirement, has to be carefully considered in order to avoid poverty traps and help sustain incomes.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks an anonymous referee and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on an earlier draft. The author also thanks François Rycx for helpful comments on an earlier draft. Previous work of the author with Stephan Kampelmann and François Rycx has been used extensively in the article [12]. The chapter on part-time work in the OECD Employment Outlook 2010 also provided substantial inspiration. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and should not be attributed to the OECD or its member countries.

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Andrea Garnero