Elevator pitch

In the first decade of the 21st century, the Brazilian economy experienced an important expansion followed by a significant decline in inequality. The minimum wage increased rapidly, reducing inequality with no negative effects on employment or formality. This resulted from economic growth and greater supply of skilled labor. However, from 2014-2021, real wages were stagnant, and unemployment rates surged. Inequality rose again, although only marginally. Some positive signs emerged in 2022, although it is still too early to know whether they mark a return to past trends or a recovery from the pandemic.

Key findings

Pros

Unemployment rates are declining and are now lower than the pre-pandemic levels.

Real wages declined rapidly during the pandemic but are now recovering.

Average years of schooling continue to rise, following the trend of the past decades. Returns to schooling continue to decline, contributing to reducing inequality.

Gender and racial earnings gaps have reduced substantially since 2001.

Cons

The recession that started in 2014 caused real wages to stagnate.

Although there has been a recovery in 2022, it is not yet clear whether it is a renewed upward trend or just the convergence towards pre-pandemic wage levels.

The long period of inequality reduction in Brazil came to an end in 2014.

It is possible that factors that allowed inequality to decline in the 2000’s will not be effective in the coming years.

The share of formal labor workers reached a peak right before 2014 and is now declining.

Author's main message

Inequality reduction in Brazil between 2001 and 2014 resulted from factors that allowed for pro-poor economic growth. These included increases in the real value of the minimum wage, a larger supply of skilled workers, and declining informality. After 2014, economic recession led to an increase in unemployment and informality that disproportionately hurt those at the bottom of the wage distribution. To spur economic growth in an inclusive manner, Brazil should implement reforms in its social protection and tax systems, aiming at enhancing efficiency without reducing coverage, as well as guaranteeing access to high-quality public education to every young Brazilian.

Motivation

Brazil is the largest Latin American country and shares with its neighbors several characteristics: it is an upper middle-income economy with low investments in human capital and high inequality. In the last two decades, Brazil experienced two very distinct economic scenarios. From 2001 to 2014, there was a consistent economic expansion coupled with a large reduction in inequality. This period was interrupted by a recession that started in 2014 and lasted for nearly three years, which was soon followed by the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Since that year, real wages have stagnated and inequality has started to rise again. Understanding these dynamics may provide important policy lessons for other countries in the region and across the rest of the developing world.

Discussion of pros and cons

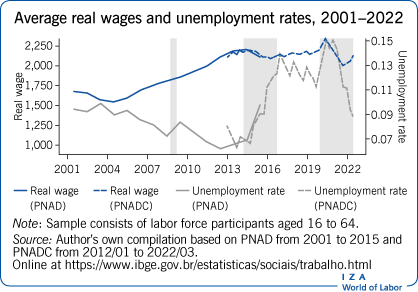

Brazil experienced rapid economic growth in the beginning of the 21st century. The illustration on p. 1 shows that the average real wage increased by nearly 30% between 2001 and 2014. Similarly, unemployment rates declined from around 9.5% in 2001 to just above 6% in 2013. The Great Recession in 2008 did little to alter the path of higher labor earnings and lower unemployment rates.

However, Brazil entered a long recession period in 2014 that was shortly interrupted between 2017 and 2019, only to return again with the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. During the recession, unemployment increased from 7% in 2014 to 14% by 2017. Real wages growth stalled as a consequence, and have since remained steady at around 2,200 reais (2019 prices). There were some signs of an economic recovery between 2018 and 2019, but it was all lost during the Covid-19 pandemic. Unemployment rates, which had been declining in the previous years, increased from 11% to 15% in the first months of the pandemic. Real wages increased slightly at the onset of the pandemic due to composition effects, as lower-wage workers lost their jobs earlier. However, they soon started to decline as well, reaching a minimum of around 2,000 reais in the first quarter of 2022.

The good news is that 2022 brought about what seems to be a rapid recovery in economic activity. Unemployment rates declined fast and are now below 9%, the lowest level since the end of the 2014 recession. Nonetheless, despite the reversal of the previous downward trend in employment, real wages are still below their pre-pandemic levels. This is due not only to a slow increase in nominal wages, but also an acceleration in inflation rates that has affected many countries, Brazil included. Therefore, although the increase in employment is certainly much welcomed, the new jobs created are not as good as those created during the pre-recession period.

Declining inequality during the 2000’s was halted by the 2014 recession and Covid-19

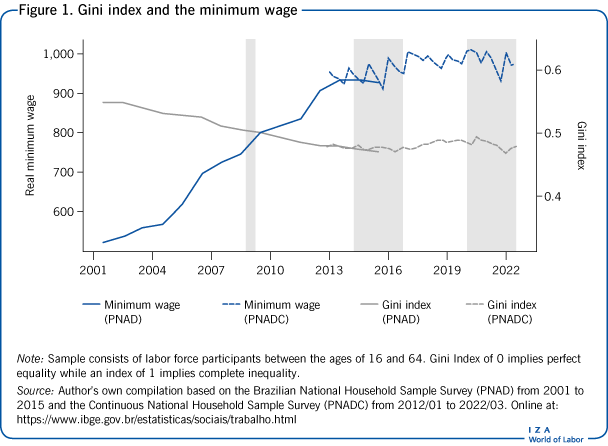

One of the most striking features of the Brazilian economy at the turn of the century was its reduction in inequality. It is important to notice that this trend was not exclusive to Brazil, but can be observed in many other Latin American economies [1]. This is a particularly important achievement when contrasting it with the rising inequality observed among developed countries since the 1980’s [2] and considering the historically high levels of inequality in the Latin American region. Figure 1 shows the evolution of the Gini index (a measure of inequality) in the last two decades. Between 2001 and 2015, it decreased from 0.55 to 0.47.

There were many factors behind the decline in wage inequality in Brazil up to 2014 [3]. In addition to those factors discussed in this article, recent research ( [4], [5]) argues that the minimum wage played an important role in reducing inequality in the early 2000’s. Figure 1 also plots the evolution of the real minimum wage in Brazil during the same period. Between 2001 and 2013, the real value of the minimum wage rose at a fast pace, from a little above 500 reais to more than 900 reais in 2013, almost doubling in real terms. A 2022 study estimates that nearly 45% of the decline in inequality in the formal sector between 1996 and 2018 was accounted for by these minimum wage increases, including direct and indirect effects [4].

The economic slowdown brought about by the 2014 recession also marked the end of the period of declining inequality. The Gini index, which reached a historically low level of 0.47 at Figure 1 the onset of the recession in 2014, has slowly increased since then. Although research has not yet examined in detail the reasons behind the recent rise in inequality, it is reasonable to believe that it is closely linked with the economic slowdown. Economic growth before the 2014 recession enabled a steady increase in the minimum wage that led to sizable inequality reduction without any noticeable negative effects on employment or informality [3], [6]. As the economy entered a recession period, the minimum wage ceased to increase. At the same time, the rise in unemployment rates affected mostly low-skilled workers, increasing inequality through a higher education premium as well as composition effects [7]. Other factors associated with the decline in inequality also reversed direction after the recession.

The Covid-19 pandemic prompted a decline in wage inequality in 2020 and 2021. However, rather than a return to past trends, it is more likely due to changes in the composition of the labor force that resulted from lockdown measures. As can be seen in Figure 1, this small reduction did not last the whole period and was reversed in 2022. This same year also marks a return to pre-pandemic unemployment rates and a small recovery of average real wages (see the illustration on p. 1).

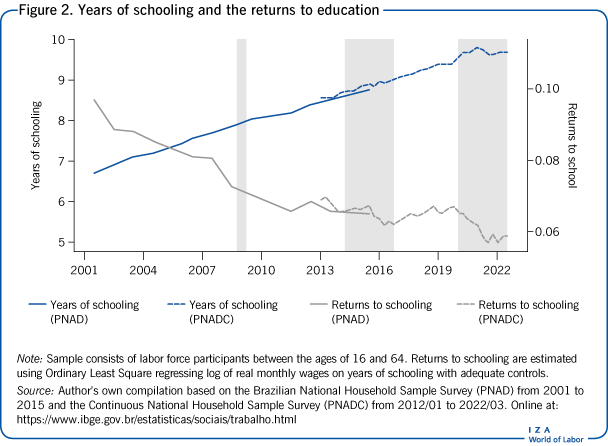

The rapid growth in the supply of more skilled labor, represented by an increase in the proportion of workers with complete secondary and tertiary degrees, has been pointed out as an important determinant of Brazil’s decline in wage inequality [8]. Although recent research disputes the claim that a greater supply of educated workers unambiguously reduces inequality [3], there is a consensus that higher supply of skilled workers contributed to a decline in the size of the education premium [5], [9].

Figure 2 depicts the fast growth in average years of schooling in the past two decades. In 2001, the average worker had studied for fewer than 7 years, not even enough to complete primary education. This number rose to nearly 10 years of schooling by 2020. Although this number is still low, advances in the provision of education have been consistent and are likely to continue in the following years, despite setbacks brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Not surprisingly, returns to education also declined quickly during this period. In 2001, one additional year of schooling was associated with wages around 10% higher. By 2014, this premium was reduced to less than 7%. The recession that followed slowed down the reduction in the returns to education, despite a continuing rise in average years of schooling. During the pandemic, however, returns to schooling decreased again. It is not clear whether the swift decline in the returns to schooling is solely the consequence of abrupt changes in workforce composition or a return to past trends from the early 2000’s. Nonetheless, the ongoing increase in the supply of more educated workers is a trend that should continue in the next few years, bringing with it general equilibrium effects that go beyond the returns to education.

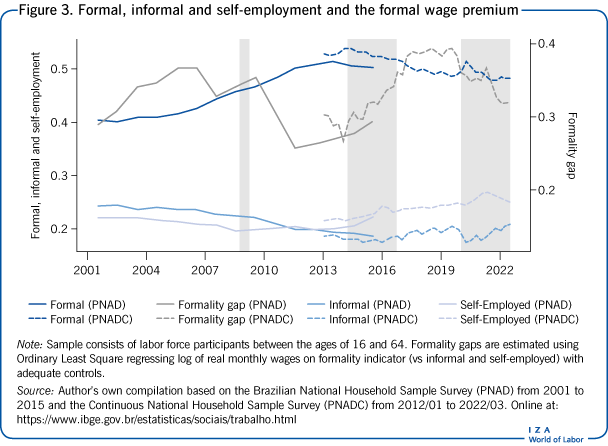

Labor force composition with rising formality

One equilibrium effect of increased education is the rise in formality. A study from 2021 shows that higher levels of education were the most important force reducing informality between 2003 and 2012 [10]. Figure 3 depicts this trend. In 2001, 40% of the workforce was employed in formal jobs. These jobs not only pay higher wages, but they also give access to social security, severance payments, and retirement benefits. The expansion of the formal sector up to 2014 happened at the expense of a reduction in informal work and self-employment, both of which declined from around 25% from 2001 to around 20% in 2014. More importantly, increases in formality came about in a period of rising real minimum wages, as shown in Figure 1. Counterfactual analyses suggest that, without changes in workforce composition, the real increase in the minimum wage would have resulted in more informality, which could have hampered its inequality-reducing effects [10].

Trends in formality reversed with the 2014 recession. The share of formal workers began to decline in 2014, a pattern that continued during the pandemic. The proportion of the workforce in formal jobs went down from a peak of 54% in early 2014 to 48% during the pandemic. Despite this drop, the share of formal workers in the labor force is still larger than in 2001. This slight decline in formality was followed by a continuous increase in the share of self-employed workers rather than informal ones. The share of self-employed workers, which surpassed that of informal workers around 2012, grew during the 2014 recession and the pandemic. This is presumably not only the result of slower economic growth, but also the result of changes in institutional settings that made it easier for workers to become legal entities and be hired by firms in short-term contracts. These changes will thus likely continue in the short and medium run. Although these contracts offer upside to workers, particularly in the form of lower taxes and more flexibility, they also entail a reduction in benefits and lower revenue for the government and the pension system. These are challenges that the Brazilian government will have to deal with in the future.

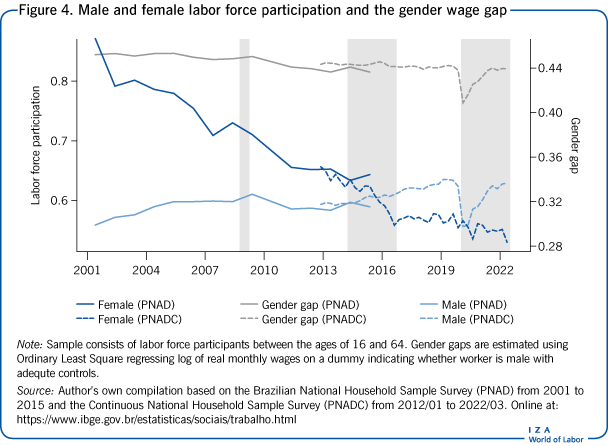

Figure 4 presents data on labor force participation for men and women aged between 16 and 64 years old, as well as trends for the gender gap in wages. Trends in labor market participation have been roughly steady in the past two decades. There was a small increase in female participation in the first half of the 2000s and another one in the late 2010s, while male labor force participation declined slowly up to 2014. Along this trend of relatively higher female labor force participation, there was a continuous decline in the gender wage gap through the whole period. The reduction in this gap continued during the 2014 recession and the pandemic, although it slowed down after 2017. It is likely that women’s participation will continue to grow in the near future (or at least not reverse) and gender gaps will continue to decline.

Figure 4 also complements the information in the illustration on p. 1 by providing a fuller picture of the unemployment patterns in the last two decades. A swift reduction in labor market participation was observed for both genders at the onset of the pandemic, followed by a steady recovery that has reached pre-pandemic levels by early 2022. Unemployment, however, has shown a much larger reduction in the same period. This means that employment has actually grown in the last couple of years and that the decline in unemployment rates was not merely the product of reduced labor market participation. Hence, the recovery might lead to a continuous decline in unemployment and possibly a reduction in inequality. Nonetheless, it is still too early to be certain about likely labor market trends after Covid-19.

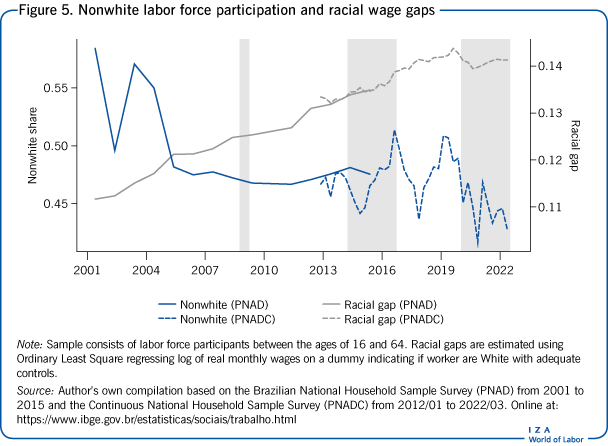

As with gender wage gaps, the White-Nonwhite wage gap also declined between 2001 and 2022 (Figure 5 ), from around 14 log points to less than 11 log points, although much of the decline took place in the early part of the period. There was a continuous increase in the share of Nonwhites in the workforce, but this phenomenon has much more to do with demographic and racial identification changes in Brazil [11] rather than an actual increase in Nonwhite labor force participation with respect to Whites.

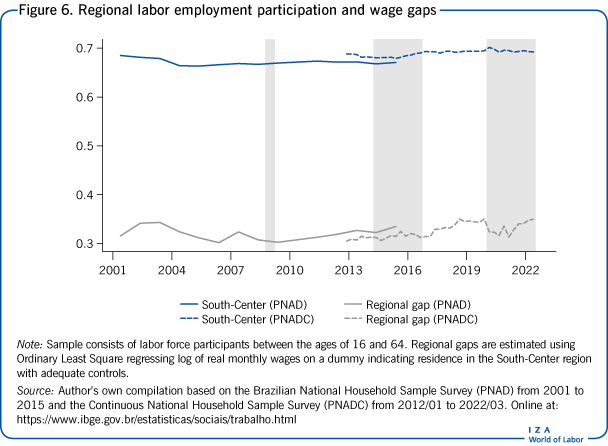

Another important source of differences in the Brazilian economy is its large regional heterogeneity. Figure 6 summarizes the main regional disparity in Brazil. The North and Northeast regions are much poorer than the South-Center region, which includes the largest Brazilian cities, such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. There was not much variation in relative labor force participation between these regions from 2001 to 2022, with the South-Center region containing nearly 70% of the Brazilian workforce. Similarly, regional wage gaps remained stable in the last 20 years, at around 33 log points.

Limitations and gaps

The most important limitation of any descriptive analysis using survey data in Brazil arises from the changes brought about by Covid-19. It not only affected labor markets, but also the quality of surveys collecting labor-market data. The problem is especially true for rotating panels, such as the one employed by the Continuous National Household Sample Survey (PNADC), as there is considerable non-response by incoming households. At the same time, sample attrition has also risen, particularly among households in the bottom of the income distribution. It is difficult to assess the direction of the bias and how it affects labor statistics and our inferences from them.

This limitation is even more challenging due to the large size of the informal sector in Brazil. Earnings and employment statistics from administrative data cover only the formal sector and do not even include formal domestic work, which employs a considerable share of the labor force. Therefore, a fuller picture of labor market conditions will only become clear as the consequences of the pandemic recede and response rates to household surveys return to their pre-pandemic levels.

Summary and policy advice

Between 2001 and 2014, the Brazilian economy went through an inequality-reducing period of expansion. Real wages increased, unemployment declined, and growth was highly pro-poor, therefore bringing down inequality. Economic growth allowed a real increase in the minimum wage of more than 100% without negative impacts on formality or employment, which played an important role in driving inequality down.

The 2014 recession brought this trend to an end. Real wages stagnated, and unemployment increased. There was a small increase in inequality, and the share of formal workers started to decline. They were replaced by informal and self-employed workers, especially the latter. The slow recovery that followed after 2017 abruptly ended with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic. Unemployment surged and real wages declined.

The data suggest that 2022 marked the end of the economic crisis that resulted from the Covid-19 pandemic, but it is still too early to know exactly which direction and, more importantly, how fast the Brazilian economy is going to move. The experience of the past two decades shows, however, that inequality reduction not only can take place simultaneously with economic growth, but that it is a required component for promoting a more equal earnings distribution.

Economic growth is the result of many factors; in at least one of them, human capital expansion, Brazil has been particularly consistent, although there are some concerns over the overall quality of the education provided by the public school system. Challenges also remain in reforming Brazil’s social protection and tax systems in a way that preserves the current safety net, but under more progressive fiscal and tax collection policies and without large distortions to economic incentives [12], [13]. These reforms should reduce the cost of formal jobs in Brazil, design cash transfers so they give incentives to formal rather than informal work contracts, and increase the rationality and progressivity of tax collection. Although there were important trade reforms in the past, Brazil is still a considerably closed economy, and this issue should be addressed to improve productivity. Finally, as the economy starts to grow again, the real gains in the minimum wage should continue to guarantee that low-wage earners are not left behind.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks two anonymous referees and the IZA World of Labor editors for many helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. Version 2 of this articles updates figures and adds findings on the effects of Covid-19. It adds new Further readings as well as new Key references [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [9], [10], [11], [12], and [13].

Competing interests

The IZA World of Labor project is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The author declares to have observed these principles.

© Sergio Firpo and Alysson Lorenzon Portella